Articles/Essays – Volume 32, No. 3

Anne Perry’s Tathea: A Preliminary Consideration | Anne Perry, Tathea

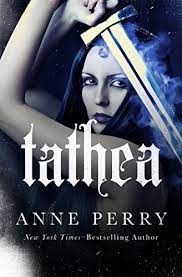

The publication of Anne Perry’s Tathea in September 1999 under Deseret Book’s Shadow Mountain imprint marks a significant literary mile stone in Mormon letters. Although Tathea’s appearance was heralded by The Salt Lake Tribune and the Deseret News, LDS-centered journal editors, either standing all amazed at this imaginative theological thunderbolt or overwhelmed by the bulk of the 522-page tome (the same number of pages as in the English edition of The Book of Mormon), remain curiously silent about this important Mormon cultural event. The fact is Anne Perry, the inter nationally famous writer of nearly three-dozen, well-received mystery novels set in Victorian England, with seven million books in print, and the most famous and widely published Mormon author (including Gerald N. Lund, Orson Scott Card, and Dean Hughes, and excepting only Mormon himself) has stepped outside of her ac customed genre to write a fantasy based spiritual autobiography which renders in Tathea’s epic journey-to the-light the Essential Mormonism to which Perry converted in 1967 and to which she continues a fervent disciple.

Some of Perry’s readers, accustomed to the familiar eccentricities of astute London detectives William Monk and Thomas and Charlotte Pitt, seem dismayed at their favorite author’s generic switch, even though she continues to produce her two-per-year quota of Monk and Pitt mysteries. On Amazon.com, readers register responses ranging from “disappointment,” “tedious,” “rather dull,” and “she’s lost a lot of credit with me,” to “one of the most beautiful books I have ever read,” and “on par with the great fantasies, adventures, spiritual journeys done by Tolkien and Lewis,” and “a remarkable, clever, and poignant book that defies the norms of modern fantasy and demands to be read.”[1]

Although Tathea contains a mystery or two, readers must grant Perry her donnee and follow her epic hero, Tathea, on her spiritual journey, in which Perry explains her own deeply felt Latter-day Saint convictions “concerning who we are, why we are here on this planet, and where we are hoping to go when this life is over and God finally says, ‘Welcome home.'”[2] Tathea becomes Representative Woman, whom we vicariously follow on her Salvation Journey, a journey which also traces the spiritual history of God’s dealings with His mortal children—on whatever world they may be found.

In Tathea, which Perry originally dedicated to a number of friends, including “Russell M. Nelson[,] for set ting the star to follow,”[3] one senses her profound purpose in writing the book: “Everything else I’ve done,” she said in a recent interview with Dennis Lythgoe,

has been moving toward this [book]. The inspiration came from who I am. I believe very strongly that one of the most powerful ways to reach people who do not wish to open the scriptures and who are not actively searching for something is to tell them stories. You can move people by stories, whether they wish to be moved or not.

Bearing her witness of the Restored Gospel, says Perry, makes Tathea “the most important book I’ve written to date[;] indeed it may well be the most important that I shall ever write.”[4][5]

The genre carrying Tathea’s spiri tual quest—which could be called Tathea’s Travels or The Magnificent Jour ney—might be called epic fantasy—although it bears little resemblance to classic fantasy; or it could be considered religious allegory—although its figures are only occasionally Bunyanesque (except for the minor character of Sophia, who is, she tells us, wisdom); or perhaps the novel is Christian apologetics—although Perry is more didactically overt than J. R. R. Tolkien, and is nearer, yet different from, C. S. Lewis; or the book might be called a Bildungsroman or a rite de passage through humankind’s several estates, ala Nephi Anderson’s Added Upon, The Book of Abraham (especially chapter 3), or O. S. Card’s free adaptation (in his Homecoming series) of the Lehite wanderings, or—inevitably we turn to what were likely the greatest influences on Perry’s imagination, namely Lehi’s visionary journeys in 1 Nephi and mankind’s pilgrimage to holiness as represented in the House of the Lord. After all is said and donneed, however, Tathea thumbs its literary nose at generic categorization and takes a form distinct and unique in Mormon letters, if not in world literature.

The setting of Tathea, according to Perry, although not readily deduced from the book, is “on another world, not unlike our own, about two thou sand years ago.”[6] The strange and exotic pre-technological cultures which Tathea visits in vision or in person vaguely suggest ancient Rome, Egypt, barbaric northern Europe, and renaissance Venice, but, again, are distinctive. The racially varied peoples and societies which Perry depicts share Earth’s all-too-familiar capacities for good and evil, love and hate, avarice and generosity, sorrow and joy, hope and despair, folly and nobility. The characters in Tathea are not subtly nuanced or psychologically dynamic: they are epic characters, good or evil, who become better or worse, according to their embrace of truth. In an attempt to humanize Tathea, Perry dangles moral and ethical temptations before her, but the reader does not for a moment believe this otherworldly saint will fall, even to learn the value of repentance.

The Prologue: Preparing for the Journey

The book divides naturally into a Prologue: Preparing for the Journey; Part I, The Vision of the War in Heaven; Part II, The Book and the Mission; and Part III, The Coda: The Words of the Book. The prologue be gins as Tathea, wife of the Isarch of Shinabar, “the oldest civilization in the world,” awakens in the night to find her young son and royal husband murdered in a palace coup. Spirited into the desert by a loyal servant, the spiritually shattered Tathea takes ship and sails, Ulysses-like, through the dreadful Maelstrom to exile in the Lost Lands, where she seeks out the sage “who was said to know the meaning and purpose of all things” (13). To her queries, “Why do I exist? Who am I?” (26), the old man, directing her quest “to know the mind of God” (26), sends her to the seashore to prepare her soul to receive further light and knowledge.

The Pre-Existence: The Vision of the War in Heaven

In the dawn, Tathea’s guide, Ishrafeli, an angel and a Christ-figure but not the Christ, comes for her in a skiff, asking only, ‘Are you sure?” “I am sure,” she answers (28), and the pair embarks upon five distinctive but the matically related journeys. In Parfyrion, she encounters Cassiodorus, a triumphant general who is conspiring to rob the city of its agency; learning that his course is “the age-old pattern of all tyranny” (48), she unmasks him as “a shadow of the Great Enemy.” Cassiodorus pronounces a malediction on Tathea, which recurs in each of the sub sequent journeys: “Woman,… I know who you are. I have your name on my hands and I shall remember you in all the days that are to come” (50). In Bal Eeya, Tathea, acting like Charlotte Pitt in Perry’s mysteries, detects and ex poses the woman Dulcina as a selfish servant of the Great Enemy; where upon she, too, swears in her hatred for Tathea, “I’ll find you wherever you go.” (77) Next, Ishrafeli and Tathea travel to Malgard, where the rulers have banned change, pain, sadness and death. Ishrafeli, in singing a plaintive song, introduces the city to the dark night of the soul which makes more joyous the subsequent soaring to great light, and he understands that, “I have broken a dream with the hand of awakening” (97) and has brought about the fall of Malgard. Tathea, shocked at the pain which truth has caused the innocents, complains to Ishrafeli, who teaches her that, “our pain is incomplete if we suffer only for ourselves” (98). After exposing the leader of Malgard as yet another servant of the Great Enemy, who desires to keep his people in ignorance, they undertake their fourth journey, into the frozen Lands of the Great White Bear where they join Kolliko and his band in warfare against the evil Tascarebus and his barbaric army. When Kolliko is killed Ishrafeli says, “my friend has gone his way and kept his first estate” (109), and the alert reader (you and I), in an “ah-hah” experience, begins to sense that we are track ing Tathea through the pre-mortal existence, a fact which is confirmed by Sophia, who encourages them in their “journey of the soul,” and explains that, “what you have learned here you will never entirely forget, and it will serve you … in your second estate, when you will have forgotten this” (121). Tathea and Ishrafeli arrive at their fifth destination, Sardonaris, a Venetian-like city of canals ruled by the secret acts of the Oligarchs. Separated from Ishrafeli, Tathea, attacked and wounded, is taken home by Ellida, who possesses the gift of healing (she will reappear in her Second Estate as the Lady Eleni, a healer). Be trayed to the Oligarch Tallagistro, yet another “Shadow of the Great Enemy” (144), Tathea is delivered to execution in scenes which suggest the betrayal and execution of “our [unnamed] brother” (151) who died for all mankind in all worlds.

Spared from death at the last moment, Tathea is directed to a long, pillared gallery, where she concludes her journey through the pre-mortal existence by being allowed to enter into the holy presence of God, “Man of Holiness” (147), and to witness in vision the Grand Council in Heaven and the ensuing war. The first speaker be fore the Council is new to Mormon theology—he is the humanist Savixor, who posits an egotistical humanist agenda for mankind, “this most marvelous of all creatures.” Such a self-sufficient creature “does not need gods!” he haughtily exclaims (149). Then another steps forward, “so like Ishrafeli and yet unlike him,” thinks Tathea: “I am Asmodeus,” he says, leading us back to the script; “I have a plan that is better than Savixor’s. I will save every soul that is given me. Not one of all the millions shall be lost[;] not one shall perish or fall into sin!” (150). He concludes ringingly: “I will bring back every soul as perfect as I receive it; therefore follow my plan and let me have dominion over them—and the glory” (151).

In response, Ishrafeli comes forward, “sweet and sure, without shadow, yet as she had never seen him before” (151). Speaking not his own words, Perry carefully explains, but “those of our brother who has already redeemed the flesh of all worlds from the corruption of physical death,” Ishrafeli outlines a plan whereby every man must have choice, agency. “Let this be the plan,” he concludes: “a world where every good and every evil is possible. Let man choose for himself, and the glory be thine.” The Man of Holiness declares, tetragrammatonly, as in the Book of Abraham, “Let him choose…. Prove him, that he may work his own salvation and inherit glory, dominion and everlasting joy, for this is indeed why he was born.” Transfixed by what she has witnessed, an exultant Tathea realizes, “This was the truth. This was what she had been searching for and paid such an agonizing price to know” (153).

The Book and The Mission

At this crucial and culminating moment—the end of her quest—Tathea is introduced to The Book, “covered in beaten gold and set with chrysolite and pearls,… its workmanship unlike any she had seen. Its great hasp was set with a single star ruby” (153). She reads the first words: “Child of God, if your hands have unloosed the hasp of this Book, then the intent of your heart is at last unmarred by cloud of vanity or deceit.” It continues by revealing what Latter-day Saints call The Law of Eternal Progression: “When God was yet a man like yourself, with all your frailties, your needs, and your ignorance, walking a perilous land as you do, even then was the law irrevoca ble.” She reads further: “By obedience you may overcome all things, . . . until no glory is impossible. By such a path did God ascend unto holiness” (154).

Filled with the power and spirit of The Book, Tathea understands her charge: “She would take [The Book] back to the world, share with everyone this treasure, this key to all happiness” (154). Ishrafeli leads her into the presence of God: “In the center [of the room] stood one Man alone, and in His face was the love that has created worlds, and before whose beauty the stars tremble” (156). The Man of Holi ness places His hands upon her head, and His words, “written on her soul,” stress mankind’s divine lineage, divine potential, and divinely assured agency to choose in all things:

I bless you to go forth in the world and teach My Word to all the people of the earth, that they may know they are My children and may become even as I am, and inherit everlasting dominion and glory and joy. But they are agents unto themselves, and in all things they must choose” (156).

Then, following the ancient pat tern, as Man of Holiness exits, Asmodeus, the Great Enemy, comes, tempting, “his eyes glitter [ing] with a hatred older than time.” Ishrafeli joins combat with Asmodeus. The two marshal their fantastic forces, which recall the Book of Revelation: the terrible Manticore against the fantastic Uni corn, Basilisk against huge White Bear, and Dragon of Sloth versus the White Swan of Compassion. Ishrafeli triumphs and sends Tathea, cradling The Book, back to her Second Estate, to begin her mission to the world.

The Mission

When Tathea awakens back on the shores of the Lost Lands, she has for gotten everything about her journey through the First Estate, but she has not returned empty-handed:

There was only one certainty, absolute and unchangeable, The Book clasped in her arms was the source of all that was beautiful and precious, the beginning and the end of everlasting joy. The power of the universe was in its pages. She must share it. Everyone must know (165).

She retains, as well, the knowledge that she must teach everyone that, “He was the Father of all mankind. They were begotten in His likeness”; that man kind carried “in its frail and foolish soul the seeds of Godhood”; and that life was a journey back to God (166).

Her own spiritual quest fulfilled, Tathea, still an exile from Shinabar, travels to Camassia. She establishes herself, studies and translates The Book, which is written in an ancient tongue, and undertakes to teach the words of The Book, first to Camassia, which she accomplishes by beginning with the royal family, and then to her native Shinabar, which she conquers at the head of Camassian armies. Daunted by the challenge of presenting The Book to the emperor Isadorous, she reads the familiar promise of The Book: “I give no commandment except I make a way possible for you to fulfill it, if you will work in obedience and trust in me” (191). She converts the em peror with the simple intelligence that, stripped of all his power and possessions, “you are a child of God. And that means you must learn to behave like Him” (193). The emperor, like all con verts to the words of The Book, enters into a covenant with Man of Holiness “to walk in the teachings of The Book and keep its word” (196).

At every juncture, however, Tathea is opposed by yet other manifestations of the Shadow of Asmodeus, who tempts and tries her and, on threat of destroying the capitol of Shinabar, persuades her to abdicate the throne, Alma-like. Leaving the original Book in possession of her first convert, Ra Nufis—there are now many copies of the text—she undertakes to teach The Book to other peoples.

Tathea and the high priest Tugo mir, her once-implacable enemy who makes a Korihor-like turnabout in his conversion to The Book, undertake Paul-and-Timothy- or Alma-and Amulek-like missionary journeys to convert the forest people of Sylum and the Flemens. Through her missionary journeys, we learn of the mission of “the Beloved One”:

There was a beloved Son, of whom

God spoke . . ., who lived on another world from ours, in such a way that He might answer the law and redeem worlds without number. I do not know how He did it, only that He did. I cannot touch such a thing with the furthest reaches of my imagination, but I know that it is so. .. . But if you ask God yourself, He will cause you to know it. You will feel a fire of warmth inside your heart, a radiance, and a great peace, and it will be the voice of God” (370).

Tathea’s last missionary journey takes her to the Lost Legion and into a long and thrilling adventure in the Waste Lands against Yaltabaoth and his terrible horde. She is successful in converting and bringing hope to the Lost Legionnaires, who “drank so deeply of the words of The Book,” that like the City of Enoch, “they became of one heart and mind in purpose, and every man sought his neighbor’s well being” (397).

At the conclusion of the final battle, in which she and the diminished Legion thwart the evil Yaltabaoth, Tathea receives “The Vision of the Beginning of Time,” which, “knowing it must never be forgotten,” she engraves “painstakingly on thin, metal plates which the farrier made for her because they had no paper” (408). In the vision, a kind of Gospel According to Tathea, she sees a Woman in a beautiful gar den being tempted by Asmodeus. The Woman, fully aware of her right of choice, and fully aware of the consequences of any decision she takes, chooses to partake of the forbidden fruit, knowing “I have eaten death, as well as life. But it is better so,” for “without knowledge of good and evil I cannot become like my Father. I know that I walk a knife blade between light and darkness” (405).

As the vision progresses, Tathea learns that, just as the blessing of the fall came about by one heroic woman in a garden making a crucial choice, so mankind’s future “depends on one man in the meridian of time, who had offered to live without stain and at the appointed hour, to face Asmodeus in another garden.” Tathea sees the Woman “put it to her lips and ate,” thereby launching the “exile of the great journey, with all its trials and pain, its labor and grief.” And, we read, Tathea “loved [the Man and Woman] with all her heart” (405), and all believing men and women who came thereafter “kept faith that in that white instant at the center of time, one man would come who would stand alone in a garden and look upon hell, and he would not turn his face away from it” (406).

In the same Alpha and Omega vision, Tathea sees the advent of the Beloved. Listen to Perry’s moving rendering of her Gospel:

The moment came, the day and the hour. The man was born. He be came a child, and then a youth. . . . And the man came to maturity with a pure heart and clean hands and began to preach the Word of God with power. Some listened to Him, many did not … . He shed light about him, those who feared the light conspired against Him, and the weak, the cruel, and the self seeking . . . hated Him with a terror because He showed them the truth, and they could not abide it. .. . It was the moment. They sought to put Him to death, and He prayed alone in the garden. His soul trembled for what He knew must come, and He longed to step aside, but He knew at last what weighed in the balance. Eternity before and after hung on this one battle.

And they took the man and killed him, and He died in the flesh. But His spirit was whole and perfect and living, and all creation rejoiced. The dead of all ages past who had kept faith with Him awoke and were restored, and those who had died in ignorance were taught in accordance with the promises of God. And the man returned to the earth to tell those who loved Him of His victory, and they believed and were filled with a hope which no darkness could crush or devour.

They taught in His name, and some believed, and some did not. And when they passed from mortality into immortality, their words became perverted, even as the man had foreseen in the face of hell. Evil things were done in His name, and twisted doctrines spread a new kind of darkness over the world. But even while there was ignorance, war, corruption, and tyranny, there was also love, courage, and sacrifice, and a hope which never quite faded away. Again men waited and watched and prayed.

Then came the Restoration (though never called such in the novel):

And after a great time, truth was given anew out of heaven, and the old powers were restored, and the old persecutions, because as ever the Word of God was a sword which divided the people, and a mirror which showed a man his face as it truly was (406-408).

Tathea returns to Shinabar, where she learns that Ra-Nufis, her first con vert, has betrayed The Book and led the nation into apostasy, violating the people’s agency, perverting “the doc trines of God” (445), promising life without pain, teaching a false God, establishing a professional priesthood, introducing non-related ritual, and asserting that “Ra-Nufi’s interpretation of The Book is the only correct one” (463). Threatened with death by the jealous priesthood, Tathea storms the underground vault where The Book is kept, kills Ra-Nufis in a thrilling encounter, and flees with The Book, which she takes back to the Lost Lands, battling onboard ship the Unrepentant Dead, who are dispersed only when her companion raises his right arm and commands, “In the name of Him who faced the powers of hell and overcame them, I command you to de part!” (495).

Coming full circle in her long and arduous journey in defense of truth, Tathea returns to the Islands at the Edge of the World. Overcoming one last temptation by the tenacious Asmodeus, whom she at last recognizes as “the corruption of what had once been sublime,” and, resisting his last temptation, rebukes him. Carrying The Book, Tathea is met at the ancient seashore by a man “like Asmodeus, slender and dark with a face of marvelous beauty, and yet he was also utterly different. In him was the knowledge of pain and glory, and his eyes shone with the light in his soul.” Instantly she remembers Ishrafeli from the First Estate and recalls the lessons of her early visions. Ishrafeli gives her a sur prising final charge:

You took the fire of truth from heaven. You must guard it until there comes again one who is pure enough in heart to open the seal and read what is written. It may be a hundred years, it may be a thousand, but God will preserve you until that time and the end of all things. In that day I shall come again, and we shall fight the last battle of the world, you and I together (504).

Ishrafeli kisses her and walks into the sun, leaving Tathea on the shore, “the golden book in her arms and the fire and the light of God in her soul” (504). She waits there yet—and will wait there until the sequel, expected next October, when she will find the boy who will “raise the warriors who will be righteous and strong enough to fight Armageddon.”[7]

Coda: The Words of The Book

In the process of translating and teaching the words of The Book to the people, Tathea introduces the reader to the words and message of The Book, until she has gradually revealed and interpreted most of its contents of The Book, which Perry presents in its entirety in a seventeen-page coda. The prologue to The Book begins: “The conversation between Man of Holiness and Asmodeus, the Great Enemy.” The body of The Book is a transcript of the Great Conversation, during which Man of Holiness describes His Plan of Salvation, and Asmodeus presents his dissenting and antithetical responses. For example, The Man of Holiness, echoing the doctrines of Joseph Smith’s King Follett Discourse, says in stately words, “It is My purpose and My joy that in time beyond thought he may become even as I am, and together we shall walk the stars, and there shall be no end.” But Asmodeus counters, “[man] is weak and will despair at the first discouragement. But if you were to set lanterns to his path of rewards and punishments, then he would see the good from the evil, and his choices would be just.” And when the Man of Holiness promises that the obedient man will one day hold “My power in his hands to create worlds and dominions and peoples without end,” Asmodeus retorts: “He will never do that! The dream is a travesty!— Give him knowledge, a sure path. He will never be a god, but he will be saved from the darkness within him” (507).

The Man of Holiness tells Asmodeus that it is not about power, as he mistakenly believes; “It is love . . . it has always been love” (508). At the heart of His plan is agency. “I will not rob man of his agency to choose for himself, as I have chosen in eternities past, what he will do and who he will become.” “Wickedness can never be joy,” He intones. “Even I cannot make it so” (508). The journey to godhood requires obedience and self-mastery: “If he would become as I am, and know My joy, which has no boundary in time or space, then the first and greatest step on that journey is to harness the passions within himself and use their force for good. Without that he has no life but only a semblance of it, a fire-shadow in the darkness.” He insists, “There must be opposition in all things; without the darkness, there is no light” (517). Asmodeus argues that in exercising agency man will abuse the procreative powers “above all the other powers you give him. He will make of that desire a dark and twisted thing. . . . He will corrupt and pervert, distort its very nature until it grows hideous.” But Man of Holiness persists: “I know it, and My soul weeps. But it must be. The more sub lime the good, the deeper the evil that is possible from its debasement” (509). Still, He says,

I know him better than he knows himself. I give to every soul that which is necessary for it to reach the fullness of its nature, to know the bitter from the sweet, which is the purpose of this separation from Me of his mortal life. It is a brief span for an eternal need, for some too brief for happiness also. But to each is given the opportunity to learn what is needful for that soul, to strengthen what is weak, to hallow and make beautiful that which is ugly, to give time to winnow out the chaff of doubt and impatience, and fire to burn away the dross of selfishness. The chances come in many forms and ofttimes more than once (510).

But at the end, to Asmodeus’s scornful question as to why Man of Holiness would undertake all of this “for a creature who is worthy of nothing?” God replies, “It is because I love him. . . . That is all. It is the light which cannot fade, the life which is endless. I am God, and Love is the name of My soul” (522).

The Question of Style: Conclusion

Ipresent these lengthy citations from The Book in order to address the question of style in Tathea, which is at once off-putting for readers accustomed to Perry’s mystery novels, and “virtuous, lovely, .. . of good report or praiseworthy,” for those who read the book not only as an epic, full of sound and fury and profoundly significant, but as alternative holy writ, paraphrasings of God’s Word, and close to the mark. Perry’s style in Tathea must steer a tight course between suggesting on one page the credible and powerful presence of the divine in human life, on whatever world; while evoking in the next pages exotic desert and frozen landscapes, wild seascapes, and even the holy halls of God; and on a further page eliciting the fantastic through evil, malformed dwarfs, a fairy-angel with bells on his toes, ships manned by the Unrepentant Dead, horrible Manti cores and Dragons, stately Unicorns and White Swans, not to forget a princess who is a practitioner of white magic and an evil king-mother who is a practitioner of necromancy.

Not everyone will agree with me (oh happy day that would be!), but I believe she has brought it off with dis tinction in this landmark tour de force, which will hereafter occupy a distinguished place in Mormon letters. If we grant Anne Perry her donnees, or, as one of my errant-prone missionaries used to plead, “cut [her] a little slack,” I am persuaded that she has brilliantly negotiated a literary Scylla and Charbydis and written a book which is even more than what she calls “a gripping story of love and conflict that also looks at the great challenges in life— the nature and meaning of who we are.” Tathea is vitally important to Perry herself, and, by implication, to every covenanted Latter-day Saint, dealing, as she describes it, with the moment of consecration,

the dilemma each of us could potentially face when we are allowed to receive something that is so important we wish to share it with others, but realise [sic] that in doing so we will put our own lives considerably at risk. At that point, we reach the crossroads and have to ask ourselves if we believe in what we are doing enough that we would be willing to give up all we have for it, if necessary even our lives.[8]

In writing Tathea, Anne Perry has courageously, put her career on the line in proclaiming her faith in and consecrating her talents to the Restoration, by revisiting and rendering, however obliquely, the Plan of Exaltation, and she has done it in a fantastic, magically realistic, exciting, refreshing, and spiritually moving way which heeds Emily Dickinson’s counsel to “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant.”[9]

[1] Amazon customer comments.

[2] ‘Anne’s Own Comments,” The Perry Chronicle: The Journal for the Discerning Detective 2, no. 8 (Nov. 5,1999), 5.

[3] Jacket blurb of Tathea, 4.

[4] [Editor’s Note: There is no footnote 4 in the PDF]

[5] ‘Anne’s Own Comments,” p. 5.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Lythgoe, ‘Anne Perry,” E3.

[8] Anne’s Own Comments.

[9] #1129.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue