Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 2

Another Angel

And I saw another angel fly in the midst of heaven, having the everlasting gospel to preach unto them that dwell on the earth, and to every nation, and kindred, and tongue, and people.

Revelation, XIV:6

I

Professor R. L. Robinson woke up on a jet from Los Angeles to Paris and discovered that his wife of one day was not in her seat. He had fallen asleep during the movie, and she, it was clear, had turned off his headset, and the overhead lights, and left him to it. The champagne had done—no, was still doing—its work. It was close to midnight by his watch and the plane was quiet; the spaces—inside and out—mostly dark.

He turned himself on and began a survey of the radio channels. Comedy: it was that Vietnamese kid who did a take-off on Ted Kennedy. Rock: Bob Dylan’s old “Popera.” Next was Mozart, so he lingered. He packed his pipe and relit—but it wouldn’t hold—so he put it back in his pocket. He closed his eyes again.

When he opened them there was light coming through the window, and the seat beside him, he noticed immediately, was still empty. It was certain now that his wife had collapsed in the restroom, and no one suspected what lay behind the locked door. She had been sucked out of a faulty hatch and had plummeted, silently, into the Atlantic—while he snored. For a few seconds, Robinson’s mind rang drowsy changes. Then he was moving up the quiet aisle.

He found her, sitting in the empty forward lounge. She was hunched over—elbows planted in uplifted knees, chin wedged in her hands. A stubby paperback was open on the table in front of her, and her face was concentrated. As Robinson entered, one hand started down to turn a page.

“Good morning,” he said.

“Well hello,” Holly said, straightening up, smiling. She pushed a strand of brown hair from her eyes.

He sat down. She kissed his cheek.

“The film was a bore,” she said. “I didn’t want my light to bother you.”

“It wouldn’t have,” Robinson said. “I was blind. In fact I still am, a little.”

He glanced to see what her book was. “You’ll never guess what I’m reading,” she said.

She took the book by the open halves and turned it over. He saw hazy, vertical bands of bright and pale blue, and on the right side a golden figure, robed to the ankles, standing on a gray ball. The right hand held a long, single-stemmed, golden trumpet to the lips; the head of soft curls angled back—blowing a blast. On the other side was the title, The Book of Mormon, in white letters.

“Where on earth did you get this?” he said, taking it from her.

“At the used bookstore,” she said. “Do you mind?”

Robinson closed the book and turned it over in his hands. It had a familiar weight and thickness; except that the ones he remembered had black covers and smaller angels.

“Charles told me you used to be a Mormon,” she said. “I was just curious.”

“He did, did he,” Robinson said, handing the book back. He took his pipe out while Holly lit a cigarette. When the stew came by they could get some coffee.

“Look at this,” Holly said.

She turned to a page that had a dark ballpoint circle around a verse. Robinson leaned over and read:

2. Now I, Nephi, did not work the timbers after the manner which was learned by men, neither did I build the ship after the manner of men; but I did build it after the manner which the Lord had shown unto me; wherefore, it was not after the manner of men.

“It’s so repetitious,” she said.

“Yes it is.”

“It’s all sort of like that,” she said. “It isn’t anything like the Bible.”

Robinson struck a match. “Well,” he said, between puffs, “it was all written by one man.”

“That’s not what they say.”

“No,” he said. “But the style is his, at any rate. That’s what gives it that wordy tone.”

He reread the passage.

“It sounds like he’s buying time,” he said. “Trying to think of what to say in the next verse. He just repeats himself until he’s ready to move on.”

Holly was nodding and tapping her cigarette, so Robinson read another verse. This raised two images in his mind, and he knew the connection between them perfectly well. The first was of a young man in farming clothes, sitting in a room that had been divided in half by stringing up a blanket. There was a wooden box on the floor near the man, and he was holding a black hat, upturned, in his hands. He was bent over, gazing at a stone in the bottom of the hat. On the other side of the blanket there was another man, dressed like a schoolteacher, sitting at a desk. Every now and then the man with the hat would say something, and the man at the desk would write it down.

The second image Robinson saw was simply himself as a young man, reading The Book of Mormon on a bus headed into Los Angeles.

***

“It’s really strange,” Holly was saying. “A bunch of Jews build a ship and go floating off to South America. It’s sort of like what you’d get if you asked John Bunyan to rewrite the Aeneid or something. Maybe it’s some kind of folk epic disguised as a bible. Is there anything in print on this?”

“Nothing respectable,” Robinson said. “There might be, by now,” he added, “but I wouldn’t know about it.”

“I bet I could track a lot of this down in English and early American sources. Folklore, sermons, things like that.”

“A lot of people would be grateful if you did,” he said. “But I wouldn’t recommend it.”

“Why? It’s American lit. It’s in my field. I’m surprised you haven’t done it.”

“I wouldn’t touch it,” Robinson said. “It wouldn’t be worth your time.”

“Why?”

“Because there’s nothing there. There’s nothing literary about it. It’s simply propaganda.”

***

He glanced out the window. They were over land now, a horizon of small farms, purple-grey in the dawn. The one place this does not look like, Robinson noted, is Utah. But that was a thought he had not expected to have on his honeymoon.

***

“Do you think those witnesses really saw the gold plates?” Holly was saying.

“Nope.”

“Do you think they lied?”

“Who knows,” he said. “I think they thought they saw something. I think they wanted very badly to see something, so they did.”

“It does make you wonder,” she said after a pause.

“The book is designed to make you wonder,” Robinson said. “That’s the best reason I know for not believing it.”

“How did you come across it in the first place?” Holly said. “Your parents aren’t Mormons.”

“There was a girl,” Robinson said, trying to find the right tone.

“Your first wife?”

“No. Before that,” he said.

“Now we’re getting somewhere.”

“If you like.”

II

Senior English, Inglewood High School, 1957. Robinson, Smith—we sat together on the back row. She was new—from Utah. A Mormon. Her parents owned a restaurant, and they were getting rich because they gave ten percent of everything they made to the Mormon church and tried to keep all of God’s commandments. I was a Methodist, but I told her I had no morals and she threatened to “send the missionaries over.” She couldn’t keep religion out of her head—not for more than a few minutes. But she also worshipped Scarlet O’Hara, and she had read Kings Row twice and Forever Amber. Some days she wore so many crinolines she had to fold herself into her desk. She had a nineteen-inch waist, but she wanted a waist that a man could circle with his two hands. Her mother had had nine kids, and she was going to have twelve.

I was president of the class, but I didn’t have a date to the graduation prom. I didn’t even think to ask her until the last minute. She wasn’t what I would have called pretty. She was a little too tall; her hair was too curly on top, and (this puzzled me) slightly darker in back. Her cheekbones were too high and rosy, her mouth was full of teeth and her calves were skinny. She made up for these defects by trying to have what we called in those days “a great personality.” She thought it was almost sinful to be shy. She also thought it was possible to be romantic without “committing adultery.” She had been “sweet-sixteen-never-been-kissed.” Unfortunately, her younger sister hadn’t even made it to fifteen. It finally dawned on me that I was amused by the way she talked (partly because she shamelessly flattered and flirted). I figured that if we didn’t “make out” after the prom, at least there would be no awkward silences.

***

“I’ll bet it was a blow to your ego,” Holly said.

“It surprised me,” Robinson said. “I don’t think I’d ever been turned down before.”

“You mean you had to become a Mormon before you could take her out?”

“Not really. It was just a bluff. But I fell for it.”

***

She was dying to go with me (I could tell), but when they came down from Salt Lake the girls had all taken a vow not to date non-Mormon boys. But she promised to plead my case at their next family council if I would just wait a few days and please not ask anybody else. After all, this was her once-in-a lifetime high school graduation, so she deserved a teeny-weeny exception.

***

“Did they open your mouth and examine your teeth?”

“Not quite. I remember they asked me a lot of questions about my family and my goals in life. They wanted to know what church I went to and whether I thought it was ‘true’ or not. I never thought much about my church one way or another. I was just a Protestant like everybody else.”

“Deep down you probably felt like telling them to shove it.”

“I should have.”

“I can just see you, with that murderous little polite smile on your face. I’ll bet you decided to seduce her then and there.”

“Not hardly,” Robinson said.

***

There were at least six bedrooms, two fireplaces and a maid’s apartment over the garage out back. The front door was eight feet of solid something with a big brass knocker in the middle, and just inside there was a stairway that would have made Rhett Butler pause. Carma slept in a four-poster bed with a pink canopy—I was allowed to see it on my short tour, accompanied by a chorus of giggling sisters.

But they hadn’t lived this way for long—they let me know right off that this had all started with a small cafe in South Salt Lake. They were new money, full of enthusiasm and wonder at their success. We sat in the panelled study and her father played and sang a hymn on their new organ. A couple of the little girls recited poems and her mother gave me a copy of Think and Grow Rich. Carma’s older brother was a missionary in Finland. They showed me his picture with the girl who was waiting for him to come home so they could get married. I was uneasy, but I liked them all right away and I think they liked me. I felt from the beginning that I was going to “pass,” and that this was just a formality that would have to be endured. Her mother especially thanked me for helping Carma with her English papers. She said if it hadn’t been for me Carma probably wouldn’t have graduated. She said the rule about not dating non-Mormon boys was entirely the girls’ idea, and the girls, she announced, had voted to make an exception in this case. All the little ones clapped and cheered at this, and I blushed—which made everybody laugh. After that, we had refreshments. Carma’s mother wanted me to understand how important a temple marriage was to each of them, and I acted as if I did when really I didn’t.

Graduation night Carma said that for every person living on earth there were at least a hundred evil spirits who wanted to inhabit their bodies because they couldn’t have one. Her little cousin flew around the room until her father called the demon out by the power of the priesthood. The Three Nephites and the Apostle John were still alive and might turn up anytime, anywhere; and there was a place called Kolob, which was a star or something where God lived where one day was equal to a thousand years. Somebody was doing genealogy work and found a hundred-year-old newspaper on their doorstep one morning. Utah looks just like the Holy Land turned upside down, and there are pictures in the National Geographic to prove it. Joseph Smith saw God the Father, and his son Jesus Christ, the Angel Moroni, Elijah, Moses, John the Baptist, Peter, James, and John—and if you had faith it could happen to you too.

I was sitting in the kitchen one night thinking about these things. I had finished the Book of Mormon, and I believed in a church I had never attended. My parents were away on vacation, and I was sure something terrible was about to happen, because people who had faith received visitations. And they were twice as tempted and tormented because they had found the truth. Two hundred evil spirits were probably assigned to them. I tried to read, but I couldn’t shake off the sense of a presence. Whether it was good or bad I couldn’t really tell, but I knew I was afraid of it. I wouldn’t be up to it alone. I prayed a little, and then I went to the telephone. I dialed every number but the last, waited too long and got the siren. Yes, it would look like I was doing it for a girl. I dialed the whole number. Worse yet, someday I might think I had done it for her.

An hour later I was at a Mutual dance with my two hands almost around Carma’s waist, and she was beaming up at me. After that I figured I was in love, which justified everything until the day came when I decided I had figured wrong.

***

Suppose Sister Smith, in a silky fat nightgown, had suddenly turned on the lamp and said, “All right, when’s the wedding? Don’t move, I want Brother Smith to see this. The whole house asleep, and here you two are having sexual intercourse at three o’clock in the morning. And we thought we could trust you. Get your hands off your faces, and stop crying. Look at me, young man. It’s a beautiful thing, but it’s not free for nothing. Look at this, Lloyd. Sit up now, and tell us what you think you owe one another. Rodney, I wonder what your parents are going to think when I invite them over for a little early breakfast?”

That was the only way it could have been. They lay upstairs on their bed and wondered and worried, but we were only mushing on the sofa, or grinding away in my car, or rolling around on the floor of the study until four A.M. for five straight nights, frenching until our tongues were raw. They wouldn’t have admitted it for the world, but they wanted it. It might have been my salvation, but I couldn’t take the hint they never would have thought of giving. A thigh for a thigh.

***

Carma and I, at the piano in the living room. I’m trying to learn how to play “O My Father.” Sister Smith strides in dressed in satiny black and a broadbrimmed black straw hat. Asks me would I like to take a little trip, to check out a restaurant she and Brother Smith are thinking about buying.

It’s about ten and we head downtown. Sister Smith steers the big Buick and tells me a story. I can see she’s happier than a sow in the shade.

“I thought you might like to see what happens to people who don’t live the principles,” she says.

A little tour of the plant. The man—husband—does most of the talking with a forced cheer plastered over fatigue. (When you’ve been caught in Vegas with one of your waitresses it takes it out of you.) The woman—his wife, his partner—offers a cutting comment now and then, when he forgets something, or when he doesn’t.

Turning lights off and on, opening closets and cupboards, explaining machinery, showing us the parking out back. Sister Smith prevents silence with questions: the help, the daily figure, their banks, suppliers—prods a naugahyde stool, clacks a freezer door. I try to look like something besides eighteen-year-old boy. Everybody knows that everybody knows.

Finally, in a corner booth. Wife brings me a coke from behind the counter, which I politely accept and dutifully sip (“Every now and then you have to,” Sister Smith says later). They talk, about $20,000 apart. I nurse my poison, all ears. Suddenly, Sister Smith turns to me, smiling roundly, and says,

“Perhaps, I should ask my future son-in-law if he thinks he can handle this.”

She chuckles, and it’s clear I don’t have to answer. Just try to look modest and happy. The owners manage faint smiles, but I see they can’t believe it. Their life’s work in my hands. I smile back, but I can’t believe it either.

They resume their haggle. Husband lights another cigarette, his hair in sandy tatters. Mrs. Fierce Menopause puts hers out. I sit there wondering if it wouldn’t be better if I went away to college first, for a thousand years.

***

“You panicked,” Holly said.

“Not right away,” Robinson said. “I was always too polite to say what I really felt, so the whole thing dragged on for months. By then Carma had left college and moved back home—to wait for the wedding, I guess, or for me to officially propose or something. I didn’t realize what was going on. I was just trying to survive Stanford. We wrote almost every day, but we couldn’t keep it alive. So when Easter week finally came I went down and pulled the plug. I thought her mother was going to kill me.”

***

“Did she make a scene?”

“Not exactly. I figured all hell was going to break loose, so I gave Carma the bad news the night before I went back. Late. Her dad I could have handled—he would have understood—but I was afraid to face her mother. So all I know is what Carma wrote me afterwards. She said her mother was thinking of suing me for breach of promise, and I guess she threatened to get me excommunicated too. Carma said she would never regret loving me because it had helped me join the Church, but she was afraid that someday my ‘lust for power’ was going to destroy me. She was always dramatic. I think she woke up her parents right after I left. All I know is her mom had her packed and half-way to Provo before morning.”

***

“Was that the last you saw of her?”

“No. I saw her at Church after that, when we were home on vacation.”

“Did you ever try to get back together?”

“Not really. We went out a couple of times, but that was about it. I had my eye on a girl up at school by then. But nothing ever came of that either.”

“What about her mother?”

“She finally cooled off a little. At least she never followed up on her threats. Needless to say, I avoided her as much as possible.”

“You were quite a cad.”

“Indeed,” Robinson said. “Let’s get some coffee.”

III

From Orly, they went straight to the hotel and to bed—because of the time change. In the afternoon they wandered along the river poking in book stalls, and that evening they rode up to the Place du Tertre and had dinner, under the Sacre Coeur.

Robinson’s book was virtually finished, so the summer looked more like a reward than a chore. In Paris he might check a manuscript or two at the Archives Nationales, but aside from that, nothing. In ten days they would cross to England; there were a few things he had to do at the British Museum and the Bodleian, but this would take a week at most. Holly had her dissertation to think about, but so far she was just reading around. After London, a drive through Scotland, Ireland. They might take a cottage for a month, somewhere. Then back to the continent.

They had both been in Paris before. This time, they decided, there was nothing they had to see, nothing to miss. They would start out late in the morning, let the Metro whirl them somewhere, and then walk back, shopping, people-watching, practicing French, holding hands. In the late afternoon find a restaurant, get a little drunk and return not long after dark. They did go to the theater twice, and once they ducked in and saw an American movie. At odd hours Holly kept at her Book of Mormon, and Robinson was reading A Moveable Feast, just for a lark.

“Guess what,” Holly said, one morning when they were relaxing at the hotel. “I think I’ve discovered the secret of this book.”

“Which is?” Robinson said, without looking up from his Hemingway.

“It’s so outrageous,” she said, “but at the same time so pious and preachy, that it creates an impression of truth. It forces it on you.”

“It works on your fears,” Robinson said, turning a page.

“I guess it’s like the big lie. The bigger it is the more powerful it is. It’s a strange feeling.”

“It’s the rhetoric,” Robinson said. “Just as you say.”

“It’s probably the same feeling you had when you first read it.”

“Could be.”

“Jesus Christ visits the Western Hemisphere after his resurrection and preaches to the Indians. The white Indians. This has got to be the ultimate American fantasy.”

“You may have something there.”

“I still can’t help wondering if by some weird chance all this actually happened.”

“It didn’t.”

“I know. But there’s something about it that makes you wonder, even when you can see right through it. Maybe it’s just the style. It’s so prepos terous. So deadpan. It’s such a flop, really. Why would somebody make all this up?”

“Why do people write books,” Robinson sighed. “A profound question.”

The next afternoon, as they were walking through the Luxembourg, Robinson said:

“This is where Hemingway first met Gertrude Stein. He says he can’t remember whether she was walking her dog or not, or whether she had a dog then or not. But this is where he met her.”

“I wonder where it was,” Holly said. “I mean the exact spot.”

“He doesn’t say.”

“I’ll bet it was right here,” she said. “That’s why you thought of it.”

“We’ll never know,” Robinson said. “Shall we stand everywhere just to make sure?”

They decided to walk to the rue Cardinal LeMoine, where both Heming way and Joyce had lived, and then down the rue Mouffetard to the Place St.- Michel where Hemingway had done some writing. When they got there they found a cafe and feasted on a baguette and Prefontaines.

“I don’t feel much like writing.” Robinson said after a while. “I don’t think this was Hemingway’s table.”

“Try not to think about it,” Holly said. “Tell me,” she added. “Are there Mormons in Paris?”

“Of course. There are Mormons everywhere.”

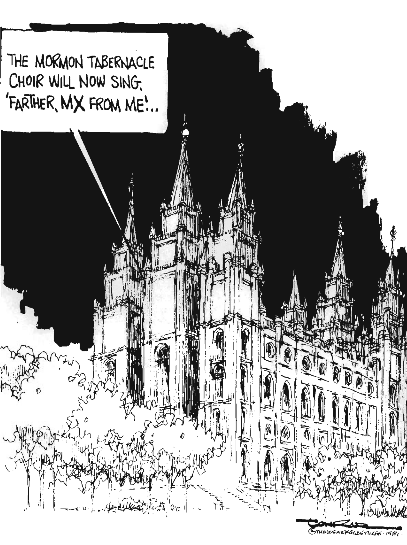

“Is there a Mormon temple here?”

“Not that I know of. There’s one in London. We can go see it if you like.” “I might like,” she said. “Did I tell you I was in Salt Lake City once? We just drove through. My father wouldn’t stop.”

“I’ll drink to that,” Robinson said.

***

Dear dead town. Always grey, always sad. Crossroads of the West, once. Now only the crossroads of a psyche. Depressing, because you know what they wanted it to become, and at the same time you see what it has become. Just another city, tired mother of suburbs. ‘And this is Mr. and Mrs. Young’s bedroom,’ your guide says, and it sounds so conventional, so singular. The sheepish tourists move down the hall. Postcards with bags of salt attached. Prostitutes on Second South joking about customers who won’t take off their garments. A town not modern or holy or clean or dirty enough to exalt or debase the imagination. ‘I lost my sugar in Salt Lake City.’

***

“Were you married to your first wife in the temple,” Holly asked, “for eternity or whatever they call it?”

“Of course,” Robinson said. “Who’s been feeding you all this stuff? Charles?”

“I’ve asked some people a few questions,” she said. “I’ll stop if it bothers you.”

“I just don’t see the value of it,” he said. “It happened a long time ago, and it’s all over.”

“You do mind,” she said.

“Not really. Go ahead.”

“Were you and Phyllis married in the temple?”

“No. Phyllis isn’t even a Mormon.”

“So in the eyes of the Church, you and your first wife are still married. As far as the next life is concerned.”

Robinson had to laugh. “It’s written on a piece of paper somewhere/’ he said. “But it doesn’t mean anything. God isn’t going to force people to stay married to each other, I don’t think.”

“What are the temples like inside? Is it just one big hall, or what?”

“Many rooms. Some big, some small.”

“What’s it like to be married there?”

“It’s different. But one isn’t supposed to talk about the details.”

“You can’t even tell your wife?”

“The last of my scruples,” Robinson said. “Merely a courtesy.”

“But why, if you don’t believe in it?”

“I’ll tell you all about it someday,” he said. “I just like to add to my guilt one drop at a time.”

“I can see you’ve really got a lot of it,” Holly said.

“I was joking.”

“But you have,” she said. “I think you can still feel guilty about something you no longer believe in.”

“I guess.” Robinson lit his pipe and glanced out at the street. It was still there—Paris.

“It doesn’t matter to me,” Holly said, “as long as it doesn’t bother you too much.”

“It doesn’t bother me at all,” he said. “What put that idea in your head?”

“It’s pretty clear.”

“In what way?”

“In the way you say things.”

“Like what for example?”

“Nothing in particular. Just everything.”

“Oh for God’s sake,” he said. “That’s ridiculous.”

“I don’t think so.”

“But I don’t take it seriously, for Christ’s sake. That’s why I joke about it. If I took it seriously I sure as hell wouldn’t make fun of it.”

“You could,” she said. “It’s not as simple as that.”

“You’re splitting hairs.”

“Not really.”

“Jesus Christ,” Robinson said. “Can’t we drop this subject?”

“If you didn’t take it seriously,” she said, “you wouldn’t give a damn how I felt about it. But it’s clear that you do give a damn. Because you don’t want me to take it seriously.”

***

He didn’t answer that. He drank up, motioned to the waiter, and they got out of there, walking back to the hotel in silence.

It was a glorious afternoon—the streets filled with banners and honking. A light breeze and a rare blue sky. Shops freshly baited with things to eat and look at. Just like the song said.

Robinson strained after it, and failed. They might just as well be walking round and round Temple Square S. L. C. His honeymoon was coming apart. Turning into a goddamned cottage meeting. Christ! He was furious—pretending to sightsee. His stomach was a tipsy knot.

He was afraid to let out his anger, for fear of losing her. But he would have to let it out, or he was sure to lose her. He touched her arm and they stopped.

“If you ever want to join the Mormon Church,” he said, “believe me, I won’t do a thing to stop you. You have my full approval to do whatever you want to do.”

He bent to kiss her but she turned away.

“Why don’t you stop being so damned polite,” she snapped. “Why don’t you tell me what you really feel.”

All right, he thought. I guess this is as good a place as any.

“I hate it,” he began. “I hate it, and I hate everything it stands for. And I’m damned mad at you for even bringing it up. I’ve spent most of my adult life trying to get away from it, so if you ever want it you can pack your bags at the same time.”

“That’s more like it,” she said.

There was a bench nearby so they sat down.

“I don’t have any intention of becoming a Mormon,” she said after a moment. “But I’m going to study it, and I think I’ll do my dissertation on the Book of Mormon. If you don’t like it, tough.”

“If it’s all right with your committee, it’s all right with me,” Robinson said. “Just don’t bother me about it.”

“Don’t worry, I won’t.”

“Fine.”

“You creep,” she added.

“You nut.” He reached over and took her by the back of the neck. There was nothing like having your first fight in the heart of Paris.

“I know what,” Holly said. “I’ll prove it a fake and destroy the Church. Just for you.”

“You don’t have to go that far,” Robinson said. “I don’t believe it already.”

They started walking again.

“Tell you what,” he said, after a few blocks. “The next time we pass a pair of Mormon missionaries I’ll point them out to you.”

“You mean you’ve already seen some?”

“I think so. I can usually tell.”

“Do they wear some kind of uniform?”

“No. Just dark suits, sometimes hats. Very clean-cut Americans.”

“That doesn’t sound like much to go on.”

“It’s enough,” Robinson said. “Some of them look like people I used to know.”

IV

Their second and last Sunday in Paris Holly got up and went to late mass at St.-Germain-des Pres. Robinson slept in, met her outside the church, and they found lunch near the Place St.-Michel. From there, they took the metro across the Seine and up to the Place de L’Etoile, wandered through the Arc de Triomphe and back down the avenue toward the Concorde, browsing idly through shops, with tickets to London marked for eight P.M. riding in Robinson’s coat pocket.

“What ever happened to Carma?” Holly asked suddenly, “I mean after you broke up, and she went back to college. What did she do after that?”

They reached the other side. She let go of his hand.

“She got married,” Robinson said, “and had five kids in something like six years. It didn’t do much for her figure.”

“You saw her?”

“Now and then,” he said. “I even had lunch with her a few times.”

“After you were married?”

“Yes. When I was in grad school she dropped by the office one day, and one thing led to another. But not to another. I never slept with her, cross my heart. I wanted to, but I never did.”

“Why not?”

“Well, for one thing she lost her nerve and told her husband. He made a big fuss. Accused her, threatened me. So we gave it up. They were divorced a few months later.”

“And you were the cause.”

“Not really. They had lots of other problems. She didn’t cause my divorce either. By that time she was remarried and had even more kids.”

“So you never did get together.”

“We never would have,” Robinson said. “I saw her a few times when she was divorced and I was still married, but there wasn’t enough there.”

“On your side or hers?”

“Mine. I was the one who cut it off.”

“Do you know if her second marriage lasted?”

“Yes,” Robinson said. “It didn’t. She’s divorced again, as far as I know.”

“You’ve seen her?”

“No. She writes now and then, care of the department. About once a year.”

“What does she say?”

“Repent. Go to church. Things like that. I guess I’m the only person she ever converted, so if I don’t make it to Mormon heaven she says she’s coming down to hell after me.”

“And what do you write to her?”

“Nothing,” he said. “I don’t respond.”

They walked on down the avenue, Robinson thinking that for a long time it wasn’t going to matter where they were, that she was going to live only in these conversations until she found him all out. So why not volunteer a little information? After all, the girl had some catching up to do.

“What about her mother?” Holly was saying. “Is she still alive?”

***

I remember we had been rolling around on the grass down at the park. While I was holding her, I slipped my hand inside her blouse and unhooked her bra, and she got mad and made me hook her back up right away.

When we were inside the front door Carma’s mother called to her immediately from the upstairs bedroom. I waited for a moment at the base of the stairs and then went into the study and picked up a copy of the Improvement Era lying on the Tostum table.’ Pretty soon I heard Carma calling, from the top of the stairs, for me.

When I came in Carma was standing flushed beside the bed with a couple of towels in hand and her mother was telling her to go downstairs and find the doctor’s number in the desk directory. I could see two or three bloody towels on the tile just inside the open bathroom door.

Sister Smith was lying flat back on the bed without even a pillow. The blankets had been thrown aside to the floor and the sheet was drawn up over her slightly raised knees to her chest, her feet elevated, like two white spires, probably on the missing pillows. Carma set off without a word or a glance. Sister Smith had a gray smile on her face for me.

“Father’s downtown,” she said. “I can’t reach him. I need a strong man.”

“What do you want me to do?” I said.

“Go downstairs,” she said, “and tell Gary to keep the little kids out back. Then I want you to go to the linen closet in the back hall and get me a large stack of towels. The big ones. I don’t want to float out of this bed before the doctor comes.”

I ran down, told Gary, and made two trips with the towels because the first stack was so large I dropped half of it on the stairs.

When I came back in Carma was in the bathroom—I heard the toilet flush—and Sister Smith was on the telephone explaining it all to a receptionist. The doctor was out. She said it was an emergency, and then she put her hand over the mouthpiece while they tried to reach him.

“I want you to help Carma clean me up a little,” she said.

Carma came out of the bathroom, and I helped her raise Sister Smith so we could put fresh towels under her, and then we spread new towels all over the lower half of the bed. I turned away while Carma sponged her mother off with another wet towel and pulled the sheet back up.

“Anything?” Sister Smith said. Carma shook her head.

Sister Smith closed her eyes and put her head back, the telephone still at her ear, and Carma and I stared at each other across the bloody bed. Finally Sister Smith said “Thank you very much,” and handed me the receiver.

“He’s going to call an ambulance and meet me at the hospital,” she said. “Carma, get a couple of my new nightgowns out of the drawer and my good robe and slippers out of the closet. And pack some things in my traincase. It’s on the shelf in the closet.”

We waited about twenty minutes, and during that time she passed some large clots and each time I helped her raise up so Carma could take them away and replace the towel. Once, while Carma was in the bathroom Sister Smith said very quietly:

“My tithing baby.”

I nodded, pretending to understand.

“I’ll bet you think I’m a foolish old woman,” she added.

“No,” was all I could say.

“Your mother would,” she said.

I couldn’t answer that, so I looked out the window. My mother would have thought it foolish, I knew, but my mother didn’t know about the millions of spirits in the pre-existence. She didn’t know they needed bodies so they could come to earth and be tested. She didn’t know how many Mormon women had given their lives for that principle.

I went down at the bell and let the attendants in. They hustled their litter up the stairs and put a dressing on Sister Smith while Carma and I pawed through the closet for the slippers. Then they eased her onto the stretcher, buckled the straps and we followed them down. The ambulance was backed into the driveway, and they opened the rear door and rolled her in. One of them opened the side door and let Carma in, and I handed her the traincase.

“We’ll be at Daniel Freeman,” Sister Smith said. Carma looked away.

“If you hadn’t come home when you did, she might have died,” Holly said.

“I doubt it,” Robinson said. “You couldn’t kill that woman near a telephone.”

“But she lost the baby.”

“Of course. But that didn’t stop her. A year or so later she had twins. A boy and a girl. She spent almost the whole nine months flat on her back and the doctor wouldn’t let her leave the hospital without a hysterectomy. Beautiful kids.”

“You’ve seen them?”

“Years ago,” he said. “From a safe distance.”

They continued down the avenue and Robinson turned the conversation to a small scandal they both knew of at the university. They passed two more blocks in this way and then stopped, when Holly turned abruptly to peer into a shop window. At almost the same instant Robinson saw the two young men, darkly dressed and looking like twins, who had come onto the avenue at the next block and were walking in the same direction, away. He fixed them for a second, then tugged at Holly’s sleeve.

“There’s your Mormon missionaries.”

“What?” she said, without looking. She took a step closer to the window.

“Mormon missionaries,” Robinson said. “I’m almost positive.”

“Where?”

He started her up again, nodding his head to indicate the ones he meant. “Those two,” he said, adjusting his stride to theirs and weaving from side to side to keep them in full view for his wife to study. They were both wearing American-style suits and ties, and one was carrying what looked like a triple combination—the Book of Mormon, Pearl of Great Price, and Doctrine and Covenants—all in one volume with a zipper cover. They were both very pale and had unusually short haircuts, and they were walking almost in step, talking and laughing. Robinson felt sure of it now, so he increased the pace.

He kept this up for about a block, not saying a word, as if his prey, the missionaries, might hear him, until he came to a difficult knot of strollers. As the knot broke, slowly and awkwardly, in front of them, he took Holly’s arm and started to push and guide her, moving into a long stride.

“Let’s catch up and meet them,” he said, shifting her quickly in order to pass a couple who had stopped, right in the middle of the sidewalk, for a kiss. “Just for the hell of it.”

He felt some resistance, but he kept up.

“Let’s not be silly,” Holly said. She seemed out of breath already.

“What’s so silly about it?” he said without slowing. “It might be fun.”

She pulled back very hard and stopped them.

“What are you doing?” Robinson said.

“I don’t feel like it,” she said.

“Why not? You’ve been talking about it all week. Why not meet the real thing?”

“I’d just rather not,” she said.

“They won’t mind.”

“I don’t want to,” she said. “If you want to, go ahead. I’ll wait right here.” She turned and looked into a dark shop.

Robinson glanced up the street at the two figures. For a moment they disappeared in the crowd. Then he saw them cross the street and go into a building. He was surprised. It was a movie theater—or was it the place next door? There were some people in the way, so he didn’t actually see them go in.

“They’re gone,” he said. “Forget it.” He turned to his wife and saw that she was still staring at her shadowy reflection in the window, her back to him. He nudged her. “Hey.” She didn’t respond. She closed her eyes. She looked like she might be about to cry. But she didn’t.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue