Articles/Essays – Volume 18, No. 1

Another Attempt at Understanding | Kathryn Smoot Caldwell, The Principle

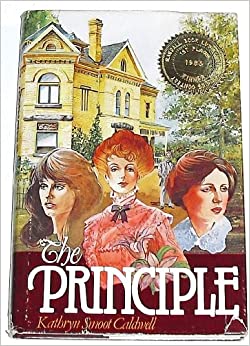

The Principle, Kathryn Smoot Caldwell’s first novel, received the significant encouragement of first prize in Randall Book’s 1983 LDS Novel Writing Contest —$500 plus a $1,000 advance on royalties. (Second and third place winners Carol Lynn Pearson and Marilyn M. Brown received advances on royalties for The Lasting Peace and Goodbye, Hello, respectively.) It is devoutly to be hoped that this contest will become an annual feature, as Randall Book has, in the last few years, pursued an extensive and aggressive program of publishing short, popular fiction. As someone who likes both popular and serious fiction, I’m glad to see this evidence that the writer publisher-reader circle is a nourishing one. Without a broad public base, any art form lacks the vitality to sustain itself long, and the virtual torrent of LDS publishing un leashed by Shirley Seeley less than ten years ago is refreshing compared to the grudging trickle of the previous forty years.

By coincidence, Kathryn Caldwell and I share a common ancestor — Samuel Rose Parkinson. As nearly as I can tell, it was in his generation that a strong matriarchal family structure began. It was also this generation that practiced “the Principle.” My great-grandmother ran things. So did my grandmother. And my mother’s three sisters. In the novel, men make the precipitating actions but women, through carrying them out day after day, really have final control of the success or failure of any given venture.

Whether this pattern was an artistic choice or simply reflected the author’s family history is not important. This book does, however, treat plural marriage once again as a women’s problem. Caldwell’s stated goal, “to understand the character and strengths of those who managed to live The Principle successfully, with dignity” (p. 1), is unfortunately limited by her decision to examine only coping skills rather than reaching for an understanding of men women dynamics, generational tensions, or even religious issues except in purely per sonal terms.

The story is set in a modern frame. Shelly has learned that the baby she carries is deformed, and she is under intense pressure from her nonmember husband to abort. Feeling depressed and uncertain, she goes through long-unopened trunks in her dead aunt’s attic containing the personal effects of Pauline and Sarah, the two wives of Horace Carter, Sarah’s daughter Caro line, and other women. “The evidences of each woman’s life were tucked carefully into the cocoon of her trunk” (p. 6).

Shelly is particularly taken with a diary that Caroline (Carlie) began in 1889 when she was seven, living on the underground with her mother in Franklin, Idaho. The diary tells of her devastation at age five when “Aunt Jenny,” hiding from federal marshalls, gave birth in the church steeple and died with the infant three days later. “Uncle Horace” is her father — another shock. At fourteen, Carlie and her mother move to Provo to share the palatial home of Aunt Polly, the first wife. Seventeen-year old Sam, locked in conflict with his father, is immediately hostile. He turns out to be Carlie’s full brother, left behind at two when the pregnant Sarah had to go on the underground. They become allies as Carlie smarts over the obvious inequities between her mother’s difficult life in Franklin and her Aunt Polly’s life of ease in Provo. Her pain is aggravated by towngirls who mock and ostracize her for being polygamous born. Only Horace’s sudden death from a heart attack resolves her resentment.

Carlie’s questions about plural marriage continue to grow and, although she finds in Aunt Polly a sympathetic listener, her questions are never answered. She and Sam do, however, make peace with her life as she learns to forgive their mother by retracing the pilgrimage the pregnant young woman had made to the farmhouse where she had been a servant.

Despite these events, much of the action takes place in talking. I was somewhat taken aback to have the seven-year-old Carlie following her father’s trial in the newspapers by herself and had to keep re minding myself that she was fourteen as she engaged in adult-level conversations for the rest of the book. Her communications with Sam seemed particularly unlikely for two teenagers. In each new relationship, she learns that she must choose between loving and hating, between resenting and accepting — certainly a valuable lesson for a teenager but somewhat unlikely to foe so completely assimilated and so fully implemented at such an age.

Given polygamy as a set of conditions and skipping over the initial decisions of what, why, and why me (all questions that also deserve to be treated in fiction), Caldwell’s exploration of the question “how” is a valid one. Her answer is summed up by Shelly who discovers that the secret of her ancestors’ strength is “their will. They chose to love when they could have hated. How very simple. How very hard” (p. 162). This answer is also a valid one. It has the kind of luminous simplicity that can strike one as either transcendent or as simple minded.

Almost the novel pursuades me that it is transcendent, but I draw back because of what seems an irredeemable flaw in the structure of the novel itself. The frame story simply does not work. Not only is it trite beyond belief — even though true — to have a descendant read through an ancestor’s diary and come away fortified, in spired, and strengthened, but the rest of Shelly’s life becomes simplicity itself after her experience with the journals.

She rejects the idea of an abortion. Her husband divorces her and gets custody of their three sons. Her handicapped daughter is born, she turns the family home into a private institution for handicapped children, her daughter dies, a professor she has met three ‘paragraphs earlier marries her, and they have a normal but rebellious daughter named Caroline who is, as the novel closes, reading through her great grandmother’s diary.

All of this slick tidiness in five pages rather offensively reminds me of the closing verses of the book of Job where somehow getting double of everything, including children, is supposed to make us feel that we have experienced a happy ending; or even that happy endings are what it’s all about. Despite my misgivings about Carlie, her discoveries were not of happy endings but of a way of coping with the ragged, jagged pieces of living. Caldwell should have quit while she was ahead.

The Principle by Kathryn Smoot Caldwell (Salt Lake City: Randall Books) 1983, 193 pp., $7.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue