Articles/Essays – Volume 01, No. 3

Thoughts on Anti-Intellectualism: A Response

Whenever a young Mormon intellectual attempts to discuss anti-intellectualism within his Church, especially in the broad, 166-year historical context attempted by Professor Bitton, it seems to me that he is faced with at least three natural problems that tend from the outset to diminish his possible effectiveness (in other words, he almost has three strikes against him before he starts):

(1) Such a discussion by an intellectual is an examination of attacks upon his own attitude, insight, and intellectual commitment. For this reason it is usually defensive in nature. It is not difficult to fall into the trap of self-pity to which, as Richard Hofstadter suggests, intellectuals are sometimes prone, and the resulting discussion will tend to lack the complete objectivity to which historians are supposedly committed.

(2) It is obvious that a study of one phase of an institution cannot present a balanced view of that institution’s historical development, or of its innate spirit. This hardly needs to be said, except for the fact that this particular issue, anti-intellectualism, is so sensitive that many will judge the essay too quickly on the basis of their own preconceptions and mind sets. Some ardent defenders of the faith will see in it, erroneously to be sure, an attack upon all that is good within the faith, while some who are critical of the Church will gleefully read into the essay a major intellectual rebellion which, I am sure, was not intended by the author. These are chances he must take, however, in approaching such a delicate subject.

(3) The complicated nature of anti-intellectualism itself militates against the success of a short essay if its intent is to present an in-depth or balanced view of the movement within the Church. The term “anti-intellectualism” came into vogue only in the 1950’s, and we are still wrestling with such problems as its precise definition, is multiple and complex sources, its possible values, the possible values and contributions of intellectualism itself, and with the fact, clearly recognized by Professor Bitton, that the very nature of anti intellectualism is constantly changing as intellectuals find new concerns in new historical settings. The best one can hope to do in the brief time and space alloted is present a tantalizing peek through the key-hole at a yet mysterious but important problem with Mormonism. This Professor Bitton has admirably accomplished.

The paper we have heard today is well informed, well written, and extremely thought-provoking. While it does not tread new ground as far as suggesting that the role of the intellectual is one of modern Mormonism’s most complicated internal problems, nevertheless it is the first essay I know of in which the author attempts to place anti-intellectualism in the broad perspective of Church history. If I understand him correctly, the major thesis runs something like this: Even though Mormon converts of the nineteenth century tended to be uneducated, they were nevertheless impressed with the intellect, and with the use of reason in helping to provide answers to religious problems. In revealing new doctrines, in preaching, and in missionary work, the appeal to reason was common, and the acceptance of truths discovered by science was hardly questioned as being at all incompatible with religion. There were, of course, undercurrents of suspicion of the intellectual, but in general Mormonism was not hostile to ideas, and was actually “shot through with the values of rationalism, of science, of education for progress, and of social reform.” In the twentieth century, however, Mormonism seems to have developed an antipathy to intellect, demonstrated by its lack of scholarly publication as well as by its resistance to new concepts of biblical scholarship, race, science, morality, and progressive political and economic reform. Again Professor Bitton notes some exceptions, but the general picture he presents is one of the intellectual it more difficult to express himself in the modern Church than he would have in the nineteenth century.

I find much food for thought in all parts of the paper, but my criticism will be limited to a few basic topics which I believe should receive further attention. In a sense this is not so much a criticism of the paper as a realization that the dialogue concerning anti-intellectualism in the Church must continue, and it seems to me that these are some of the questions that should be explored more thoroughly:

(1) First comes the matter of definition. Precisely what is anti-intellectual ism anyway? Or, to put it another way, what is an “intellectual?” In his book Anti-intellectualism in American Life Richard Hofstadter spends no less than twenty-five pages trying to define these terms, demonstrating at least implicity that no single definition can satisfy everyone. In essense, however, the intellectual is pictured as one who is concerned with the life of the mind and with the role of reason in analyzing the problems of society. Complete freedom of thought and expression are paramount concerns. These things Professor Bitton also seems to suggest. But does this mean that the anti-intellectual is ipso facto opposed to reason, or that he does not value the workings of the unfettered mind? One of Hofstadter’s most telling points is the fact that anti-intellectual ism is not the creation of men hostile to ideas. He further suggests that “intellect itself can be overvalued, and that reasonable attempts to set it in its proper place in human affairs should not be called anti-intellectual” (p. 21). Who, then, are the anti-intellectuals within Mormonism? I venture to guess that almost anyone who might be called such has taken occasional flights into the world of speculation, and has frequently emphasized the value of reason in the quest for truth, even though reason might frequently be subordinated to faith and revelation. It is obvious that no fine line can be drawn between the intellectual and anti-intellectual, but I am suggesting that in our future dialogue someone should at least try to draw some lines somewhere, if only for the purpose of creating a little more discussion on the matter of definition.

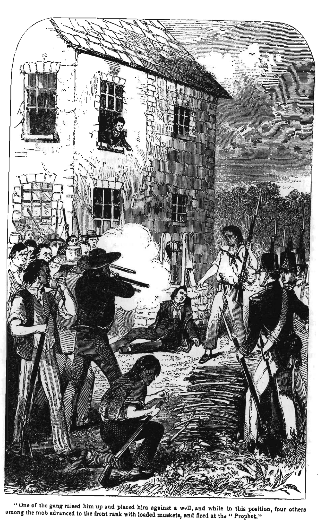

(2) A second problem in Professor Bitton’s essay appears in his attempt to demonstrate the compatibility of the intellectual with the Church of the nineteenth century. While he demonstrates his awareness of the exceptions, he is naturally reluctant to multiply examples. I believe, however, that there are enough examples to raise serious question about the extent of this supposed compatibility. Seldom, for instance, do we find Joseph Smith relying on any one else’s judgment or upon free discussion when it came to defining a doctrine. True, as Professor Bitton emphasizes, Church doctrine may have appealed to reason, but it was certainly promoted by authority. In many cases full freedom of expression was allowed only so long as it did not threaten seriously to disrupt the program of the Church. To mention only a few examples: the destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor; the disaffection of Sidney Rigdon, one of the most important intellectuals in early Mormon history; the formation of the “Council of Fifty,” with its peculiarly authoritative philosophy for the conduct of the political Kingdom of God; the fate of the Godbeites, a movement with both political and intellectual overtones in the late 1860’s whose leaders were excommunicated for disagreeing with Church economic policy; the fact that even Apostle Orson Pratt, one of the most learned of the Utah Mormons, was once required to admit publicly that he had been teaching doctrines not in accord with the authoritative position of the Church. These and other incidents could be cited simply to illustrate that the compatibility of faith with reason and free expression may not have been quite as sweeping as Professor Bitton seems to suggest. It will take much more investigation to determine this for certain.

(3) On the other hand, I am also concerned with the implication that in the twentieth century Mormonism has become less hospitable toward the intellectual. True, there is a dearth of scholarly literature (but neither did it abound in the nineteenth century), and many intellectuals have become unpopular within the Church after playing the role of gadfly, some of them becoming uncomfortable and even totally disaffected from the Church. At the same time, however, many people whom I would class as intellectuals, or at least as having an attitude completely compatible with intellectualism, have found a great deal of comfort and accommodation within the Church, and I think investigation would show that certain trends toward better accommodation actually began to set in early in this century. In the 1930’s, for example, certain Church educators became convinced that there might be too much “in-breeding” in Mormon education. As a result, certain promising young scholars teaching in the Church system were requested to leave Utah and go to eastern universities for advanced learning, with the idea that their return with new-found wisdom and knowledge of the world would upgrade the total educational program of the Church. Some of these men still play important roles in Church education. Furthermore, such twentieth century General Authorities as Brigham H. Roberts, James E. Talmage, Joseph F. Merrill, John A. Widtsoe, Adam S. Bennion and Hugh B. Brown have shown particular interest in the intellectual, and themselves have demonstrated noteworthy scholarship in some of their writings. It is also significant to note that long before world War II teachers of religion in the Church school system were particularly stimulated by Dr. Adam S. Bennion to conduct workshops and discussion groups at a very high intellectual level. Politically, B. H. Roberts, one of the General Authorities mentioned above, was among the most ardent supporters of the New Deal, and even saw in it the fore-runner of a coming world economic order based on principles very much like those of nineteenth century Mormon communitarianism. While it is apparently true that Church leadership today is oriented largely toward conservative Republicanism, it is also true that there are large numbers of liberal Republicans and Democrats who hold important positions throughout the Church, and who have no feeling of alienation from it.

One of the most highly respected intellectuals in the Church is Dr. Lowell L. Bennion, former director of the L.D.S. Institute of Religion in Salt Lake City, and now Associate Dean of Students at the University of Utah. Among other things, Dr. Bennion is a member of the recently-formed all-Church coordinating committee, which has the responsibility of examining the various programs of the Church and recommending adaptations to suit modern needs. It is significant to note that other members of this committee include some of the top educators of the Church. In 1959 Dr. Bennion published an interesting little book entitled Religion and the Pursuit of Truth. He wrote it for the benefit of young college students, and it is frequently used for reference by religion teachers. His main thesis is that there is no one road to truth, and he devotes a great deal of space to discussing the contributions of reason, science, and philosophy in this quest. He also suggests ways and means of interpreting the Bible, and this includes ideas from modern biblical scholarship. Certainly the acceptance of this book at least demonstrates the fact that the intellectual attitude is not wholly unpopular in Mormonism. Dr. Bennion is only one of hundreds of Mormon educators who could be classed as intellectuals who are teaching in universities all over the country, and who hold positions of trust within the Church. (And, believe it or not, there are many intellectuals even on the staff of B.Y.U.) Furthermore, a person does not have to look far in the Church’s Institutes of Religion to find many with an attitude compatible with intellectualism, and this has been true since the founding of the Institute program in the 1920’s.

These things are not said in any attempt to gloss over the very real restrictions which many intellectuals have felt, but merely to suggest that the problem may not be quite as ominous as some may believe. Incidentally, perhaps the most interesting recent development among the intellectuals is the beginning, this year, of a new quarterly called Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. Not published or officially sponsored in any way by the Church, Dialogue is edited by a group of energetic young Mormons and is forthrightly designed to appeal to the intellectual. Its more important expressed purpose, however, is to demonstrate that intellectualism and faith are not mutually exclusive, and that writers interested in any aspect of Mormonism can express themselves freely without fear of recrimination. It solicits articles from both Mormons and non-Mormons, and accepts them on the basis of quality rather than point-of-view. The immediate popularity of the new publication demonstrates a wide interest among the rank-and-file of the Church in things academic and intellectual. In spite of the fact that last week a Time magazine article quoted an un-named Church leader as saying that “Dialogue can’t help but hurt the church,” it is known that other Church leaders see real value in its publication and have quite openly encouraged it.

(4) A fourth question raised by Professor Bitton’s paper has to do with the sources of anti-intellectualism within the Church, a topic which he has not pursued far enough to satisfy my curiosity. He correctly suggests, I believe, that it stems from many sources, including the new business orientation of the Church, certain political motivations, ruralism, and the traditional literalness of Mormon theology.

(5) Finally, I would like to suggest that some future writer concern himself more particularly with the practical side of intellectualism itself, for this is the area that will most concern Church members as a whole. What legitimate fears might some have of too much reliance upon the intellectual, and what are the specific contributions he could make to the Church? In 1950 an interesting series of unofficial and informal meetings was held at Utah State University by a group of Mormon educators who were concerned about education within the Church. Most of them were among those who could be classed as “intellectuals.” One of them made a challenging remark which could perhaps explain the suspicion with which some Church leaders might view certain educators. Said he:

Teachers have a peculiar responsibility not recognized by many of them and not shared by many others in that they must bridge the generations. The channels of thinking they assume responsibility for should be in tune with the large movements and trends which are to dominate the lives of people 25 to 100 years or more ahead. Teachers to a degree should be prophets as well as scientists — prophets in the sense that they can recognize and can measure important trends and have a developed feeling for strength and direction. A teacher who can do no more than teach young people how to live in a generation that has gone is a poor teacher indeed.

To most of us this would seem logical, but in one sense it could help account for the mistrust by a few of the teacher who is also an intellectual. If such a teacher, for example, assumes an ever-so-limited role as a prophet, what does this do to the prestige of non-academic Church leaders who are sustained as prophets, and who may have views of the future which differ from those of the teacher? I won’t attempt to answer the question, but merely suggest that the question of practicality must be weighed heavily as intellectuals continue their quest for a more positive roll within the Church. Where should they play this role, and what would be their objectives? Is the intellectual really “safe” to any society? Again Richard Hofstadter speaks to the point:

In a certain sense . . . intellect is dangerous. Left free, there is nothing it will not reconsider, analyze, throw into question. . . . Further, there is no way of guaranteeing that an intellectual class will be discreet and restrained in the use of its influence; the only assurance that can be given to any community is that it will be far worse off if it denies the free uses of the power of the intellect than if it permits them. To be sure, intellectuals . . . are hardly ever subversive of society as a whole. But intellect is always on the move against something; some oppression, fraud, illusion, dogma, or interest is constantly falling under the scrutiny of the intellectual class and becoming the object of exposure, indignation, or ridicule, (p. 45)

With such a general reputation, it is indeed understandable that some leaders committed to a religious program such as Mormonism would look upon the intellectual as almost ipso facto a challenge to the perpetuation of the funda- mental goals of the Church.

In this connection, Hofstadter complicates the problem further by questioning whether or not the true intellectual can ever actually be committed to a program:

Ideally, the pursuit of truth is said to be at the heart of the intellectual’s business, but .. . as with the pursuit of happiness, the pursuit of truth is itself gratifying whereas the consummation often turns out to be elusive. Truth captured loses its glamor; truths long known and widely believed have a way of turning false with time; easy truths are a bore, and too many of them become half-truths. Whatever the intellectual is too certain of, if he is healthily playful, he begins to find unsatisfactory. The meaning of his intellectual life lies not in the possession of truth but in the quest for new uncertainties. Harold Rosen berg summed up this side of the life of the mind supremely when he said that the intellectual is one who “turns answers into questions.” (p. 30)

The implication of all this is that the “true” intellectual cannot be unalterably devoted to any one idea or program. To the extent that he is so devoted, he becomes anti-intellectual, for he is no longer raising questions, he is promoting answers. With this kind of definition, of course, it would probably be impossible to find a “true” intellectual, but it nevertheless raises the question as to just how far the Mormon intellectual would go in supporting even his own ideas once he presented them, and just how practical his contribution to the programs and objectives of the Church could be. I rather suspect that the intellectuals will always remain a minority group within the Church, as will the anti-intellectuals. The vast majority of Church members care little for the sophisticated arguments that characterize the dialogue on either side. Rather, they see the Church as an inspired program to which they are committed and which, in turn, gives them certain definite spiritual and social opportunities and values. Their concern is not so much with in-depth analysis based on rigorous scholarly discipline, but more on how to make work a practical program which they can see is for the betterment of themselves and their families right now. In this kind of environment, what practical, positive contributions can the intellectual make? Certainly there are some, and I urge future writers on the subject of anti-intellectualism to carefully consider what they are and to try to come up with ways and means of demonstrating the importance and practicality of intellectualism within the Church.

In summary, Professor Bitton has presented a challenging and valuable paper, and has certainly demonstrated the existence of a strong anti-intellectual tendency within the Church. More important to me, however, is the fact that his paper has opened the door (or, at least cleared the key-hole) on a flood of questions concerning not only anti-intellectualism but also the role of the intellectual, and the answers promise to be a long time in coming.

Rejoinder, by Davis Bitton

Professor Allen’s summary of my thesis is accurate on the whole. I do not believe, however, that I would go so far as to say that the intellectual finds it “more difficult to express himself in the modern Church than he would have done in the nineteenth century.” I had never imagined some present-day person being transported back into the earlier period. Each age must be considered in its own terms, for there were important differences of environment. Nor is it simply a matter of “expressing oneself.” What I have meant to say is that nineteenth-century Mormon intellectuals, such as they were in the context of that time, found their religion compatible with their intellectual commitments in several respects (not totally) ; and, further, that various changes have made a similar feeling of compatability much more difficult (although not impossible) in the present century.

The heart of the problem, it seems to me, is how you judge the general atmosphere. I am perfectly aware of the authoritation tendencies of the past century, but I think they are usually misread. Similarly, I am aware of individual examples of intellectuality in the present century, but I find them fewer, less impressive, and of much less influence in setting the general tone, than does Professor Allen.

I suspect that we are in substantial agreement in recognizing the inherent inability of most intellectuals to be completely at ease in any society, in deploring unnecessary affronts due to inherited prejudices, and in disapproving of any effort to so “intellectualize” the Church that it loses its vital influence in the lives of its members. But at present, if I may say so, over-intellectualizing is the least of our worries.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue