Articles/Essays – Volume 02, No. 1

Art and Belief: A Group Exhibition

Could there be a “Mormon Art”—something different, vital, worthy of both words, Mormon and art? During the school year 1965-66 this and related questions were being discussed much around the B.Y.U. art department, mostly on an extracurricular basis. Typical of these numerous in formal discussions was one which took place in the graduate students’ painting lab during Fall Semester. Larry Prestwich, who had just exhibited a series of drawings based on the Book of Mormon, was talking with Trevor Southey, a Rhodesian who recently joined the Church, about the prospect of new distinctively L.D.S. art; and Larry finally suggested, “Let’s have an exhibit.” Trevor had previously visited the Salt Lake City Public Library and had made acquaintance with the person then in charge of art, who had given him a tentative invitation to have an exhibition.

One of the students who became deeply interested was Dennis Smith from Alpine, Utah, one of the most searching and experimental of those who later contributed work to the exhibition. It was he who towards the end of Spring Semester invited a group of those interested to his home where we all bared our feeling, and began to make plans. We decided to each make a strenuous effort to produce some work that would represent our desires and intentions as well as we could, and Trevor was to finalize the arrangements with the Salt Lake City library for an exhibition in December. Many other ideas were discussed, such as a summer festival of fine arts for the Provo area and the founding of an art school. The dreams for the future grew and grew until some pictured the area becoming a world art center with positive new kinds of art supercede “Pop,” “Op,” “auto-destructive art,” and what-not.

Among those who were at that first meeting there was quite a variety of opinion as to what we ought to paint and how it should be painted. Dennis Smith has repeatedly emphasized that each must find his own way to produce what is most meaningful to him, rather than to expect the emergence of a common style. Trevor Southey kept stressing the necessity to make our art communicative to all, so that it will actually function in building people’s faith and appreciation of Mormonism. Some said, “We should strive after formal excellence.” Others said, “Our work ought to be poetically excellent in the matters of content and expressiveness.” “We must be wary of superficial sentiment and banality.” “We should keep it positive and optimistic in contrast to much contemporary art.” “It must be emphatic enough to capture people’s attention, interesting enough to hold it, and significant enough to deserve it.”

We held meetings fairly regularly through the summer. Students from the music and drama departments sometimes attended. One time we met and listened to Dr. Crawford Gates tell of the writing of the music for the Book of Mormon Pageant. Another time we met at the home of Gerald and Carol Lynn Wright Pearson and listened to Carol Lynn recite some of her excellent, distinctively L.D.S. poetry.

Just before the exhibit was hung, we met to decide which works to include. Among those who were finally represented were some students who had not met with us up to that time. There is Mike Coleman, who believes that “Mormon Art,” if there is to be such, should involve the realistic portrayal of the beauty of nature and be similar in its aim to the work of such painters as Corot. Very different is the work of Michael Graves, who paints in a more abstract way. Another student, Stan Wanlass, submitted a painting in which he comments on the crassness and commercialism to which false religiosity sometimes descends. The others who were represented in the exhibition are my wife, Leone, and I. We have greatly enjoyed the discussions of the group and feel it an honor to exhibit with them.

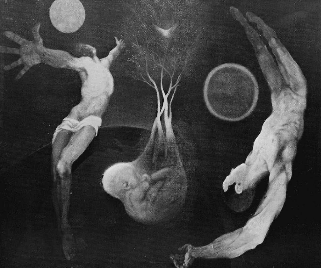

Art tends to reflect the spiritual tone of the times, the faith and hopes of the people or their doubts and perplexities. The Apostacy made inevitable the growth of a nagging, ever-increasing doubt concerning the authority of the medieval church, which has had a profound effect upon Western art. This doubt has manifested its presence—sometimes in direct expressions of anxiety and at other times in the form of compensations, hope or fervant wish standing in for faith when evidence was deficient. By the nineteenth century this doubt became more and more inescapable. When Karl Marx made his assertion that religion was the opiate of the people he was not too mistaken – given the import of Joseph Smith’s first vision. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, artists were seeking desperately to find other values outside the Christian promise to give art meaning and purpose. One hastily cast up rampart after another has been overwhelmed, and we are brought at length to open surrender to the predicament—in the black square, the soup can, the raw portrayal of sexual confusion, the twiddling of the optic nerve. It is as if mankind reaches down and feels around and discovers that, just as he feared, his pedestal is not there any more. The remedy is gone, or, as the Bible puts it, there is no water in the cistern. The modern artist sees the problem like an iceberg through the fog. There have always been good artists who stayed below decks and didn’t see it and continued to paint nice, pretty pictures, but art as a whole has moved relentlessly toward a consciousness of morality without meaning. As the Surrealist, Matta, said, “The teeth of the dragon are everywhere; all the same, I am violently against St. George.”

The critical fact of Mormonism is that it is authentic. This places the person with a testimony in a different metaphysical orientation from our brethren outside the Church. The remedy is back. The foundation is under us again, so that to paint after the glory of reality is no longer naïveté or escapism as it must seem in the world. The destiny of the Kingdom is secure. Soon the Millennium will come, and by and by the knowledge of God will cover the earth as the waters cover the sea. As this change is effected, art will change accordingly. The members of the Church who are artists will more and more realize the significance of the covenants they make by baptism and in the temples in relation to the use of their talents. The Gospel truths as they become better understood will stimulate a fresh awareness of the value inherent in all things. The artists will point out this value for mankind. In playing this new role, their work will be produced sacramentally as a free act of praise and be dedicated to the upbuilding of the Kingdom of God on earth. And Glory be! All those old masters who desired to paint sacramentally for Christ were justified after all. How good it will be to shake their hands—and also the hands of those modern artists who sounded the alarm in the dark—and all hands who receive it when the light comes on.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue