Articles/Essays – Volume 05, No. 2

Art, Beauty & Country Life in Utah

“Thank goodness I don’t have to live there! How do they stand it?” The revolting, depressing drabness and ugliness of the little Mormon towns we were driving through made my artist’s soul shiver. Never had I seen more gorgeously gaudy scenery and wide horizons than on my first trip to Utah in the 1940’s—and never more contrast between the beauty of the land and man-made patches of ugliness.

Later my life changed. I came to live in rural Utah. Though my husband was not a Mormon farmer, fate set me down on a ranch outside town, in an area scenically beautiful, economically depressed. After about a year there, I joined the L.D.S. Church.

In the thirteen years since, I have developed great affection and respect for some Mormon country people. They are my friends. No, I haven’t grown to love messiness, but I have reached some conclusions as to why things are as they are. Some I wouldn’t want to change, some I don’t know how to, and some I’m not about to try to.

In our part of the state nearly all land not federally owned belongs to Mormons. People from “outside” are barely beginning to come in, attracted by the low taxes, the outdoor life, the slow pace, or the possibilities of profit from tourism. On the other hand, young people raised here usually leave to find jobs or more scope for their talents—the land won’t support them. According to Peter Gould, geographers with computers have made surveys and maps which show that as far as a place to live is concerned, “people tend to carry in their heads an image of America with a high ridge of desirability along the West Coast that falls steeply over Utah and Nevada.”

But I believe our kind of land will be increasingly important aside from its production of beef, wool, timber, and the like. The phrase “recreational values” doesn’t quite express it. It involves an even more vital meaning in people’s lives, which a little later I’m going to try to explain.

The fact that I have chosen to speak from the aesthetic viewpoint doesn’t mean I am unaware of all other aspects from which one could write about Southern Utah; it simply means that this aspect is the one which drives me to expression.

I am a painter and printmaker who has worked in one field of art or another all of my life. I can no more help being affected by the way things look than I can help breathing. In this respect I am an oddball among most of my neighbors. Visual satisfaction means little to them—they’re too busy with “important” matters: their children, their salvation, the unending fight to make ends meet. When we try to communicate across this gap, it’s sometimes baffling to both parties.

I will say sweepingly that women are generally the motivating force behind making things look better, and any progress in that direction will be largely due to them. This doesn’t mean I think women are better, finer, more artistic, or more civilized than men. It means I think local social attitudes have caused love of beauty to be classified as belonging in the women’s department. Since masculinity has more prestige than femininity in contemporary life, it is taken for granted that men suppress, ignore, or turn into other channels their artistic energy.

This may or may not have any relation to Church doctrine or teaching. It could be a matter of interpretation and emphasis. “God’s house is a house of order.” “If there be anything virtuous, lovely, of good report, or praise worthy, we seek after these things.” “Man is that he might have joy.”

Maybe I’m wrong, but it seems not to have occurred to most Mormon farmers, sheepmen, cattlemen, miners, timber-cutters, road-builders that there is any connection between their Church’s teaching of eternal progress toward a goal of perfection and a creative, loving, appreciative interest in their environment. I have met a few local men (very few) who are concerned with the looks of their corrals and yards, a few who express real love for the landscape. Come to think of it, they are divided about half and half between Church members and non-members. I conclude these rare souls must have an unusual great inborn love of order that overcomes other considerations. But to most of them it’s irrelevant. Why?

I theorize it could never have been made clear to them that aesthetic considerations are part and parcel of the creative wellspring which could transform every corner of their lives. They have compartmented love and beauty into one area alone—priesthood and family. They have no interest in art as art, certainly, and no desire to develop their own knowledge or taste; if there is any question, they gladly accept the pronouncement of an Authority. They say,

“I don’t give a hoot for the scenery.”

“I never look up at the cliffs.”

“I never thought anybody’d want to look at the danged thing [an interesting rock formation] so I took my rifle and shot its head off.”

Despite the fact these men are rooted here, love it, and wouldn’t want to live anywhere else, they seldom express any feeling for the region’s loveliness and grandeur. Some collect rocks, arrowheads, or artifacts; but any admiration they may feel for the visual aspects of nature seems largely in articulate. Stewart Alsop has well said, “Out of our closeness to the frontier there has grown, I think, an American cult of ugliness. When survival came first, a man who cared about beauty would be hounded out of town. Out of the frontier past has grown a subconscious consensus that there is something manly about messiness and ugliness, something sissified about whatever is handsome, or well-ordered, or beautiful.”

Contributing to the situation may be the humble, unaspiring notion that anything well designed has had too much thought wasted on it, is pretentious, and “too fancy for us Mormons.” I can think of many examples of this that have stopped me cold. Thinking about it, I’ve wondered whether it isn’t bound up with a parallel unwillingness to use good English in every day speech in our part of the country. It seems to be socially disapproved as a sign of one-upness or trying to be “better’n anybody else.”

One might say there is a good solid tradition of non-neatness here. No one questions it. A perfectly acceptable status symbol is a new car parked in front. But a house and yard too well-kept, or a barn and fence in back that are clean and neat—that doesn’t mean anything! “Whyn’t you get a new car instead of that old heap?”

Once I made a list, in order, of objects piled by the front gate of a nearby ranch:

1 saddle

1 moose antler

3 old tires

1 empty Havoline oil can

2 rusty sleds

1 busted bicycle

2 five-gallon cans

3 lengths of chain

1 rubber boot

3 Coke bottles

1 rusty caulking gun

1 packsaddle

1 wad of rope

Another rubber boot

1 jeep can

2 galoshes

2 Indian grinding stones

1 clotted mass of unidentifiable cardboard and papers

Wow! I’ve sometimes wickedly wished I could see the expression on a Swiss farmer’s face were he magically transported to a layout in Southern Utah. A Swiss who has five cows is rich, yet there is no over-grazing in Switzerland, no despoiling of natural features; no tree may be cut without per mission; junk yards are concealed behind high fences; wood for the farm house is sorted by size, stacked in piles so straight you’d think a transit was used, and laid in pretty geometric patterns with evident pride of workman ship. Manure is raked into strikingly handsome, even mounds. Back yards, barnyards and outskirts of villages are so incredibly neat it makes you think all debris, garbage, and rusty machinery must vaporize in thin air—none is ever visible.

People in other rural regions as well have managed to live in harmony with nature and fit in with the landscape. I’m thinking of the Navajos, the Mexicans, the Japanese, the Balinese—all before modern civilization came, of course.

But Utah farmers are used to their way of doing things. They’ve never been to other countries. Their last surviving small farms, their little towns with inhabitants still tied to a one-cow economy (milk shed in the back) are, to the elder generation at least, a sort of ghetto. Until television came, they were unbelievably cut off from the world. But even if the people do know more of the outside, their religious beliefs reinforce habit. They’re used to being different, to never doubting the Tightness of their ways.

Reinforcing the status quo are financial considerations. It takes a lot of time and energy to keep a place cleaned up, and if a man’s working hard at something else, how can he afford the time? In some cases where people do have the money to hire it done, they have been so long cramped in the bonds of rigid economy they can’t change. It amazes me how they let saving a few dollars take precedence not only over beauty, but over comfort and convenience as well. (The glorious thing is they usually don’t let it come above human considerations.)

Bound up with the whole problem is a certain amount of human inertia, of course. After two generations of neglect it would indeed be a task to clear all the trash, scraps of wire, and rusty metal out of a pasture, or clear the accumulated fallen trees and limbs away.

But how is it such maniacal energy can always be summoned to the task of cutting down trees? Not dead trees. Live ones. The early settlers planted them. We seem to be obsessed with getting rid of them. How many times have I seen magnificent cottonwoods chopped down because (1) they “made it hard to grow a lawn,” (2) the roots were heaving the sidewalk, (3) a limb might fall on the roof, (4) the leaves obscured a business sign—when the main reason tourists would stop would be to get shade, or (5) they were in the way of one out of several possible routes surveyed for a highway.

Nobody, nobody at all, protested when local power company employees went through small towns amputating every tree on Main Street (the towns’ only real attraction) instead of merely trimming the limbs around the wires as is required by law elsewhere. The town of Mt. Carmel had all trees on the road through town cut down years ago. The town of Torrey assassinated a row of giant trees along a side street (a wide dirt road actually, with no sidewalks, then or since) because they were four feet over a hypothetical sidewalk line on a town map.

To balance things off, sensitive artistic perception is found when one least expects it. Perhaps it’s inborn like creative talent, and later events accidentally bring it out.

When my husband and I designed and built a house using local labor, we used many native materials such as lichened rocks, juniper trunks, weathered gray timbers. People are still coming to see this strange thing.

“Why would anyone spend a zillion dollars on a new house and then put some kind of gunk on it to make it look old?”

“You going to varnish them old planks, aren’t you?”

“Why didn’t you get some new bricks instead of that old stuff?”

But we heard also:

“Well, I’ve been cutting them junipers for fence posts all of my life, and I never noticed till now they’re beautiful!”

“When I first saw you getting them old shack boards to use on a wall inside, I thought isn’t that the damndest thing, but now you’ve got ’em in, I like ’em. It’s an oddity.”

Some of the local workers seemed truly to enjoy contributing, and showed real talent in craftsmanship as well as in helping to arrange the landscaping. They seemed to take pride in the finished whole. We don’t flatter ourselves we’ve had any transforming influence on the community, but of course people do incalculably influence each other. Things are changing in our county. Children come back from college, from missions abroad. Ideas come in, circulate, and germinate. In the short time I’ve lived in Utah I’ve noticed definite improvement in civic beautification, town clean-ups, use of modern agricultural methods, better service to the traveling public.

As I say, women are usually responsible for initiating these projects. Of course they couldn’t have carried them out without the men’s help. If the women had the physical strength, I believe they’d have long ago found the time to tear down the eyesores, haul away tons of junk, remove worn out cars slowly sinking into the earth at the spot they breathed their last gasp, or get a few yards of gravel to spread in front of the house to make it possible to get out of the car without stepping in mud.

This is but one of local women’s frustrations. They have to cope with more than men do—not only the common external pressures, sometimes including the demand for heavy labor, but biological functions to which their whole lives must be adjusted. They not only have to make the best of everything, subject themselves to the priesthood, adapt their lives to the patterns of their men’s, but are trapped by the inexorable demands of child bearing and rearing, which in their economic stratum often means years of first-class slavery.

I stare in awe at the miniscule log cabins in which families of ten or more children are known to have been raised; at the ancient lonely blackened farmhouses without conveniences, where women managed to keep house for years without going queer; at the forlorn children’s graves bounded by homemade markers. I’ve talked to women who can remember when there was no doctor, only a couple of midwives, in an area of over 20,000 square miles. I’ve heard hair-raising tales of pioneer women’s deaths in childbirth. My hat is off to all these country women. They didn’t just “come in and grow flowers after the men got things cleared away”; they had it the worst.

I sense in many of the farm wives I know, in spite of their sometime indifference to appearance, a reaching out, a hunger for beauty which undeveloped taste prevents from finding a channel. I’ve heard it expressed wistfully, resignedly—

“I’d like to live just once where you didn’t come in through the corrals and have to come into the house through the kitchen!”

“I’m tired of sweeping mud out of the house. This winter I just give up.”

“The winters ain’t so bad but it’s the danged spring that goes on for so long.”

“I think I need a vacation, but I don’t know how I’m going to get one.”

“When we first come, I spent two years getting the yard and corrals cleaned up, all by myself. Now we’ve moved to another farm, and it’s just as bad. I’m not going to do it this time. It’s nothing but a waste; John, he don’t care.”

“That’s a purty tablecloth. You care a lot about them kind of things at first, but after you git a few babies, there ain’t no time.”

“Them danged cows got in the yard again and ate up all the stuff I planted! Darvon, he can’t seem to get the fence fixed so they don’t get in.”

In spite of these rare complaints, which no one seems to take very seriously, many women I’ve met are happy dynamos of energy during the years of raising their families. Obviously they take real satisfaction in cooking, sewing, keeping house, and mounting a continuous attack on dirt and dis order. To me they seem more secure and content than their city sisters, although their interests are far narrower.

Probably it’s only lack of education, tradition and opportunity which prevents them from blossoming out with some kind of folk art, from wearing more imaginative clothes, or insisting on good design in objects of daily use. I’m sure they have the ability; it just hasn’t been channeled that way, for reasons too complex for understanding.

In other cultures, as Franz Boas notes, even the poorest people have produced work of aesthetic value in decorating their tools, their houses, their clothing. I think of the modern Quechua women on the altiplano of Peru and Bolivia, a locality reminiscent of Utah. They too are busy having babies, and they work in the fields. They are so poor as to sometimes be totally outside the money economy. They produce folk art—woven, knitted, and embroidered articles that are ravishingly beautiful. Their color sense is so sure that they come up with costumes so brilliant they make well-heeled foreign tourists look tacky.

How do they do it, when we don’t? For one thing, the Andean Indians have no access to the cheap, badly designed manufactured articles we are wallowing in. They’ve been handing down their knowledge of pottery and weaving technique, color and design for two or three thousand years. In all that time they’ve not had enough contact with the world outside to break up their traditions.

Our Utah women haven’t that kind of background. They don’t nurture originality. They treasure little things like a “boughten” TV ornament made of shells, coral, plastic flamingos and palm trees; or a quilt or pillow they’ve made in Relief Society from a copied design; or a bad reproduction of a bad painting.

I can see why. No one has shown them that good design and function can be part of everything they handle—not a separate thing kept in a compartment labeled “luxury.” These little bits of beauty bring them pleasure while they live in a daily scene of disorder, clutter, and confusion—which can be as much a destructive force as hate, meanness, or evil.

I understand perfectly why, when they are able to move a step up the economic ladder, they don’t want to buy anything Provincial or Early American, but usually enter with joy and relief into the Outer Space Modrun, overstuffed 1920 Sears catalog, chrome-and-shiny-varnish, painted velvet picture stage of taste development. That type of furnishing is almost the only thing available hereabouts; our merchants have local taste figured to a hair.

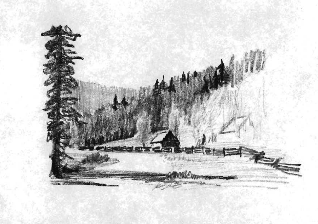

While I have no right to imply to a neighbor lady that her new furnishings are in hideous taste, I have spoken out—to no effect—when people started cleaning up so drastically that away went valuable relics of the past. Here again is a communications gap: to me, old gray fences and board corrals and log cabins aren’t necessarily crummy. Some have marvelous design and texture. My artist friends and I greatly enjoy drawing, painting, and photographing them; they’re part of the scene. But I’m frustrated because I haven’t found any way to explain to a non-artist the difference between a picturesque landmark and a scabrous old building. Particularly when some structures contain elements of both.

Summer or winter, rocks and trees and anything that’s been long in the weather have an ancient, worn kind of beauty that I love. I can find no word in English for this. The Japanese have two, wabi and sabi. Sabi means serene, lonely, desolate—a look that can be produced only by time—a sort of bloom things have for awhile before they go. Wabi means forlorn, abandoned, humble. Examples of both are plentiful in our county. I’ve seen color schemes created by the elements on junked car enamel that you wouldn’t believe. (Not that I wish to preserve junked cars in a museum.) There are old wagons, old markers, old grinding stones, wooden mining machinery, exquisite old barn boards that have been in the sun and snow for forty and fifty years. I hear in other parts of the country people are gathering these up and getting high prices for them. Utah hasn’t been picked over yet. These weathered objects, when they’re not just rubbish, convey a hint of the nostalgic, the poetic, the days that are no more. They are symbols of the fact that all things pass away, only the elements endure forever.

I’ve tried to point out this kind of beauty to local people, usually with out success. It’s too closely associated in their minds with poverty and early hardscrabble days. They are unable to find anything good in what’s old, worn, rough or natural. It seems to take a couple of generations’ remove.

I do enjoy seeing things tidied up, yes, but please use discrimination! As it is, pioneer cabins with hand-hewn square logs have been torn down. The first settler’s hut in Fruita was wiped out. Charming old Victorian houses are allowed to go to rack and ruin, way past the point where they could be profitably restored. The Bureau of Land Management has been guilty of removing many landmarks of the Old West in our area, such as the corrals and building at Eggnogg and The Post—presumably under the theory that people want a sanitized version of former days, not a reminder of the way people actually lived.

The National Park Service took apart and carted off a wonderful, great ripple-rock slab fence that once ornamented Doc Inglesby’s place in Fruita. It was very beautiful, unique, weighed tons, and wasn’t in anyone’s way, but perhaps because it was a relic of an old-timer it was thought unsuitable.

Utah schools are somewhat to blame for an attitude of non-conservation. They teach nothing of local prehistory. Indian petroglyphs and pictographs and old Indian living sites are routinely defaced by school children and strip ped of their artifacts (to be kept in a cigar box that eventually gets lost). There is no “outdoor education” such as California and many other states have been giving fifth and sixth graders for many years. Such a course would include education in conservation, scientific awareness, ecology, aesthetics based on contact with nature and appreciation of our country’s rich natural heritage of the outdoors. That kind of thing is taught in Israel, in England, in Germany and other places, but not here. In this, our school boards of course reflect attitudes of local people who have been fighting nature all their lives and can’t understand the need to re-program themselves.

It’s hard for anyone to realize how fast the situation has changed. As the rest of the world becomes more and more crowded, countryside like ours becomes rarer. Many Utah communities have been too isolated to have an overall view of their assets to the nation. For instance, the town of Boulder was within living memory reachable only by pack train—the last “pack horse town” in the United States, always snowed in in winter.

Glen Canyon of the Colorado is already gone—replaced by a dammed lake—gone because Utah didn’t have the vision or the political power to protest.

When so much of our natural landscape is being destroyed by the demands of mass housing and transportation created by overpopulation, places like Southern Utah are welcome islands where the works of man can be seen in proportion to the rest of the universe. Contact with nature is sup posed to be a human necessity. Rural Utah is about as far away as one can get from the bureaucratic-industrial complex of modern American cities, unless it’s somewhere in the Adirondacks. How often I see people who come to visit us take deep breaths as they gaze around them at the landscape with a look of incredulous relief and satisfaction mixed with longing!

Our Utah is sometimes almost too beautiful. For me, in summer and fall living here can be like eating cake everyday. Occasionally I need a visit to the city, with its vital stirring of crowds of all sorts of people and events, the free exchange of variegated ideas, the stimulation of rushing about—and the noise, congestion, smog and stink to make me appreciate quiet, space, peace and pure air! Before long I have come back, however.

Even in the stark winter aspect there is something that satisfies my soul. Not that I don’t realize on another level its real grimness: the filthy barn yards, the mud-caked livestock, the endless mud tracking into the houses (drearily exposed as needing a coat of paint), the monotony of life, the fight against cold and isolation, the daily hassle to get the truck started, the wind that blows till one is ready to dig a hole, crawl in, and never come out. Sometimes driving through town in winter I have to set my teeth and tell myself, “You chose this. It’s your habitat now. Get used to it.”

At the same time I can’t help drinking into my being the delicate loveliness of the lines of rip-gut fences scribbled against the untracked snow, the remote-looking mountains, the cozy house lights of the little towns shining out as the ultramarine dusk deepens: bleak, harsh beauty pure and clear as a cathedral bell ringing.

The fascinating textures of earth and grasses in frozen fields with varying amounts of snow powdered or blown on them are endless sources of interest. The silhouettes of bare trees and barns, or the new moon etched behind Lombardy poplars dark and sharp, make patterns so handsome there’s no end to looking and studying.

Rimbaud said, “The goal of life is the transformation of the self into a maker of poetry or beauty. This transformation is more important than anything done along the way.” To me this is the same as the Mormons’ teaching that in the highest state of life to which we may progress, the ability to perceive, savor, and to live beauty will be total. The Navajos say it too: “May you walk in beauty.”

Nowadays anyone who persists in believing in the perfectability of man should probably have his head examined. But I do know that definite advancement in sensitivity to environment can come to an individual with the passage of time.

I sometimes wonder how to hint to my neighbors that they could begin now—with small questions of taste like buying paper kitchen towels plain instead of imprinted with a bad design, or really looking at what’s around their feet when they get out in the hills. But I don’t believe in anyone’s right to impose concepts on anyone else. They must come of themselves.

Everyone who knows how to open himself to them can discover his own particular delights somewhere to counterbalance the bad things of life. To find them is vital to survival. For some, a place to retreat from the coming megalopolis will always be necessary. When the country people in sparsely populated parts of Utah see how outsiders regard their heritage, they may be inclined to hold all its aspects more dear.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue