Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

As Above, So Below: Mormonism Mattathias Singhin D. J. Butler’s Kaleidoscopic Cosmological Fantasy D. J. Butler. Witchy Eye D. J. Butler. Witchy Winter D. J. Butler. Witchy Kingdom

There are many different ways to construct a fantasy universe. Some are flowers, carefully grown from a single seed. Some are mirrors, with each element corresponding to a specific parallel in our own world for the purposes of allegory. Some are photocopies, carefully repeating standard tropes, while others are stadiums, equipped for large crowds, where games are played according to clearly defined rules. The world of D. J. Butler’s Witchy War novels is an old-growth forest, a kaleidoscope, the stomach of a shark—growing thickly with a thousand different things, constantly shifting to reveal new patterns and connections between its disparate elements, devouring everything in its path and mixing it all together in one crowded room.

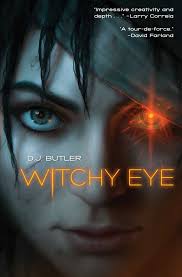

Butler’s saga began with 2017’s Witchy Eye, which was followed swiftly in 2018 by Witchy Winter (winner of both the Association for Mormon Letters Award for Best Novel and the Whitney Award for Best Speculative Fiction) and in 2019 by Witchy Kingdom. At their core, the books chart the progress of Sarah Calhoun, hidden daughter of the empress of the New World, as she battles to understand and claim her legacy. More widely, they explore the culture, theology, folklore, history, and ritual practice of a wide gamut of early Americans and magical beings. Butler’s alternate America—filled with a mass of peoples and nations sharply divided by differing interpretations of sacred texts and the nature of the cosmos and steeped in ritual traditions and ways of seeing reality beyond the material—is a place where old things become new and all belief systems are seen as tantalizing hints in the direction of a greater whole. And while this world contains no Mormons, nearly every page resonates in fascinating ways with Latter-day Saint scripture and belief.

Some of these resonances are on the surface, and there’s much to enjoy in the details: characters named Sherem and Gazalem, turns of phrase such as “measure of their creation” and “sinning against light and knowledge,” a set of eight witnesses to a holy work, or obscure references to early Mormon history, such as the inclusion of an itinerant magician by the name of Luman Walters who uses a divining rod and participates in treasure-digging. But it’s further, in the very foundations of Butler’s world and the structure of his story, in which the quest for a kingdom becomes the quest to understand a forgotten Goddess, that Butler’s kaleidoscopic imagination shines brightest.

As If It Had Been a World

As referenced above, Butler’s world is a diverse one. The cultures, languages, and religions of early America, along with a few invented by Butler, are explored expansively. English, Irish, Scots, German, Dutch, French, Spanish, Basque, Algonquin, Haudenosaunee, Ojibwe, Cherokee, Choctaw, Bantu, Igbo, Amharic, and many other tongues mix together within Butler’s Empire. And while misunderstandings and stereotypes influence the interactions between groups and individuals, Butler presents each as a vital part of the fabric of the nation. Each book emphasizes encounters between cultures, starting with the opening sequence in a crowded tobacco fair in Nashville, with merchants and visitors from a dizzying range of backgrounds all swirling together. Later sequences along the Natchez Trace, in New Orleans, and up and down the Mississippi River continue to emphasize the diversity of this society. From the beginning of the saga, the diversity of his world is cast in theologically positive terms, with Sarah’s religious mentor saying that he “loved all Adam’s children, in their colors and their smells and their busy motion and their relentless creative buzz of choice and free will” (Witchy Eye, 20). While conflict between groups is certainly not ignored in Butler’s drama, the beauty of a diverse world and the opportunity to learn from the practices of other communities are repeatedly emphasized.

The diversity of the New World and the relatively equal balance of power between its many communities are revealed in the political structure of Butler’s saga through the careful balance of treaties that form the framework of the Empire, with its system of Electors and strong regional powers. Elector songs scattered throughout the text explain how authority is shared. The peace of the Empire depends on strong respect for the individual practices of the Empire’s many peoples, no matter who or how they worship.

The many different faiths and traditions of this mixed multitude have a tremendous influence on the world’s cosmology and magic, which is shaped by the fact that many different gods answer prayers, and many different traditions offer both secret knowledge and power to influence the world through supernatural means. Christian priests, Voudon mambos, Norse godis,German brauchers, Anishinaabe Midewiwin, Tarot casters, and many others intercede on behalf of various heavenly powers. These various powers make competing claims of truth a live issue in a particularly interesting way—none of Butler’s characters dares to question whether miracles are possible, but they remain divided over who truly rules over the heavens and whether different powers can be trusted.

Out of the Books

Butler’s world certainly experiences its own wars of words and tumult of opinions, and the Bible is at the center of these disputes. In fact, the Bible plays a central role in this world that goes far beyond theological conflict. Biblical images and narratives pervade thought and speech even for characters who are not particularly devout, and especially for characters who are, such as the saintly Bishop of New Orleans. Scripture is engaged through homilies, hymns, and the stained glass and statuary of churches, but also jokes, such as those used to heckle a visiting minister, and even patterns of swearing, such as Calvin Calhoun’s repeated exclamation of “Jerusalem!” in situations of surprise or dismay.

As in our own world, the meaning of the Bible is far from a settled question, and the central conflicts of Butler’s saga revolve around how different groups interpret the creation narratives of Genesis. The elf-like Firstborn claim to be the descendants of Adam’s first wife, whom they call Wisdom, rather than Eve. Using texts that will be familiar to anyone who has read the work of biblical scholar Margaret Barker, some of the Firstborn claim biblical support for worshipping Wisdom as a goddess. Others among the Firstborn quote other passages to claim that the traditional worship of Wisdom is a heresy that violates the boundaries of Christian faith. The opponents of the Firstborn claim biblical support for their arguments that the Firstborn are soulless imitations of humanity, created by the tempting serpent from the Garden of Eden, and that they must be in submission to the Eve’s children. Since all parties quote the Bible in their defense, the Bible alone cannot resolve their disputes.

Butler also explores the idea of an open canon of scripture by introducing Firstborn religious texts beyond the Bible, both defending and opposing the worship of Wisdom. These additional texts are viewed as equal in significance to the Bible by those who accept them, but they are unfamiliar to most of the Christians in Butler’s world and are derided as heresy or forgery by some who are familiar with them but who do not believe the doctrines they teach. Two books in particular, The Song of Etyles, a Firstborn gloss on the Creation that describes Wisdom, and The Way of the Law, a text revered by those among the Firstborn who reject goddess-worship, play major roles as the question of Sarah’s own relationship with the Firstborn and the Goddess becomes more significant and pressing.

Keys of the Kingdom

Sarah’s saga is one of earthly thrones, and Butler addresses the politics of this alternate America quite ably, but the kingdom with which the books are most concerned is not entirely of this world. Political conflicts are tied to cosmological ones, and knowledge of heaven’s will is as crucial to their resolution as armies and courtiers. Thus, Sarah and her allies find themselves traveling unexpected paths, seeking answers to the sacred mysteries of Butler’s world.

From early in Witchy Eye, when Sarah’s companion Calvin is inducted as a Mason, to the climax of Witchy Winter, when Sarah completes a sacred enthronement ceremony, the subject of initiation fills the books. When Sarah asks her cousin Alzbieta at one point to explain these rituals, she is told “I cannot tell you here, or now, or in the presence of others” (Witchy Winter, 139), but Alzbieta goes on to reassure Sarah that what she wants to know will “reveal itself, in the proper place and time, to a person who has been properly prepared” (Witchy Winter, 142).

From here, many riddles are examined as Sarah seeks the sacred knowledge that will answer her own questions and give peace to her people. In one of Butler’s most direct nods to Joseph Smith, Sarah discovers that the rituals she needs have been lost, and she and her companions must reconstruct them. To do so, they depend on confidence that truth is one great whole, and that the knowledge gleaned from one initiatic path will shed light on all. In the end, Sarah encounters the heavens, but these sacred experiences produce additional questions. As she explores mysteries beyond what she would have imagined at the beginning of her journey, it becomes clear that Sarah has taken her first steps on a ladder that doesn’t end.

Roots and Branches

The world Butler has built in the three Witchy War books is diverse and intriguing, and the interlocking mysteries its characters are drawn into are fascinating. The saga combines compelling forward action with a wide range of characters, and the writing, while full of lavish descriptions, remains gripping. But perhaps of the most interest to Latter-day Saint readers are the ways in which the complex religious context and numerous scriptural debates and initiatic paths of Butler’s world refract familiar images from our own tradition into new patterns. This kaleidoscopic impact makes the three books already released a treasure trove for Mormon readers and suggests that there’s much to look forward to from future visits into the worlds of Butler’s robust imagination.

D. J. Butler. Witchy Eye. Riverdale, N.Y.: Baen Books, 2017. 576 pp. Hardcover: $25.00. ISBN: 978-1476782119.

D. J. Butler. Witchy Winter. Riverdale, N.Y.: Baen Books, 2018. 586 pp. Hardcover: $25.00. ISBN: 978-1481483148.

D. J. Butler. Witchy Kingdom. Riverdale, N.Y.: Baen Books, 2019. 624 pp. Hardcover: $25.00. ISBN: 978-1481484152.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue