Articles/Essays – Volume 31, No. 2

As Translated Correctly: The Inspiration and Innovation of the Eighth Article of Faith

The epitome of essential LDS beliefs, now known as the Articles of Faith, that Joseph Smith included in his letter to the editor of the Chicago Demo crat, John Wentworth, in 1842, has been admired by many readers.[1] It was not, however, the first such formulation. In a wonderfully detailed article, David J. Whittaker has identified several different precursors that both preceded and perhaps influenced Joseph’s formulation. He concludes that “nothing new appears in the Wentworth listing. Every item had been presented in Mormon literature before the time of its composing.”[2] In one important detail this assessment needs clarifying—that is, Joseph’s statement concerning the Bible.

When Joseph Smith wrote in the eighth article: “We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly,” he was making an innovation in creedal statements, both within early Mormonism and the broader Protestant tradition. Of the several prior formulations that Whittaker discusses, none mentions the “translation” of the Bible. The only statements that go into much depth concerning the status of the Bible are from Parley P. Pratt.[3] In a pamphlet from February 1840 Pratt writes:

We also believe in the Holy Scriptures of the prophets and apostles, as being profitable for doctrine, reproof, correction, and instruction in righteousness, and that all mysticism or private interpretation of them ought to be done away. The Scriptures should be taught, understood, and practiced in their most plain, simple, easy, and literal sense, according to the common laws and usage of the language in which they stand—according to the legitimate meaning of words and sentences precisely the same as if found in any other book.[4]

There is a similar absence of any mention of “translation” from Protestant creeds of the time. For instance, the New Hampshire Baptist Confession of 1833 has as its first declaration:

We believe that the Holy Bible was written by men divinely inspired, and is a perfect treasure of heavenly instruction; that it has God for its author, salvation for its end, and truth without any mixture of error for its matter; that it reveals the principles by which God will judge us; and therefore is, and shall remain to the end of the world, the true centre of Christian union, and the supreme standard by which all human conduct, creeds, and opinions should be tried.[5]

In contrast, Joseph Smith’s formulation places an enormous amount of importance upon the correct translation of the ancient texts that comprise the Bible. Indeed, taken literally, the veracity of the Bible is contingent upon a correct translation for readers ignorant of the original languages of the Bible’s authors. This essay seeks to explore further the attitude of Joseph Smith and other early Mormon leaders concerning Bible translation in general, and the 1611 translation sponsored by King James in particular. Second, the results of modern biblical scholarship will be employed to examine the satisfactoriness of the King James Version (KJV) as a “correct translation.” The primary focus will be on the New Testament, though occasional references will also be made to the Old Testament.

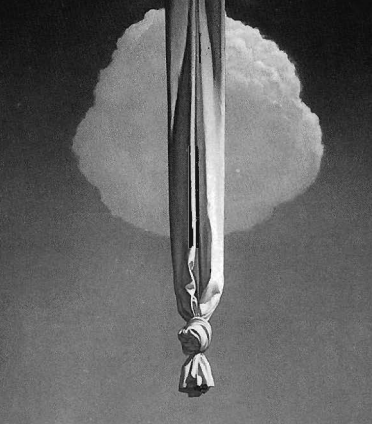

What did the phrase “as far as it is translated correctly” mean to Joseph Smith? On the one hand, it meant that any effort to render a text originally written in one language into another will never be wholly satisfactory. This notion is conveyed in the old Italian proverb, traduttore traditore, “the translator is a traitor.” The wealth of insight, subtleties of meaning, and the play on words in the original language of an author can never be completely reproduced in another language. “Translation is one of the most influential forms of literary criticism, for it both interprets and recreates the text it addresses. Indeed, in its original uses in English the word interpret meant ‘translate.'”[6]

Joseph Smith appreciated the wealth of insight that comes from studying the Bible in the original languages of its composition. In January 1836 he hired a Jewish rabbi, Joshua Seixas, to teach biblical Hebrew at the school of the prophets in Kirtland, Ohio.[7] On 19 January Joseph wrote in his journal: “It seems as if the Lord opens our minds in a marvelous manner, to understand His word in the original language; and my prayer is that God will speedily endow us with a knowledge of all languages and tongues.” Later, on 4 February, he wrote: “May the Lord help us to obtain this language, that we may read the Scriptures in the language in which they were given.” Finally, on 17 February, he wrote: “My-soul de lights in reading the word of the Lord in the original, and I am deter mined to pursue the study of the languages, until I shall become master of them, if I am permitted to live long enough. At any rate, so long as I do live, I am determined to make this my object; and with the blessing of God, I shall succeed to my satisfaction.”[8]

At a deeper level, Joseph realized the inherent limitations of human language in general. Earlier, in 1832, he had lamented: “Oh Lord, deliver us in due time from the little, narrow prison, almost as it were, total dark ness of paper, pen and ink;—and a crooked, broken, scattered and imperfect language.”[9] Joseph’s successor, Brigham Young, also shared this view: “Revelations, when they have passed from God to man, and from man into his written and printed language, cannot be said to be entirely perfect, though they may be as perfect as possible under the circumstances.”[10]

On the other hand, “as far as it is translated correctly” also meant to Joseph “as far as it has been transmitted accurately.” Joseph believed that the Bible in its current state was missing parts that were originally present. In the Book of Mormon the Lord told the prophet Nephi: “Wherefore, thou seest that after the book [i.e., the Bible] hath gone forth through the hands of the great and abominable church, that there were many plain and precious things taken away from the book, which is the book of the Lamb of God” (1 Ne. 13:28). Joseph himself made this same observation: “From sundry revelations which had been received, it was apparent that many important points touching the salvation of man, had been taken from the Bible, or lost before it was compiled.”[11]

Not only had “plain and precious things” been taken from the Bible, but things had been added that were not inspired by God. In the manuscript of his new translation of the Bible, Joseph wrote: “The Songs of Solomon are not Inspired Writings.”[12] This notion of portions of the Bible being uninspired was also maintained by Brigham Young:

How do we know that the Bible is true? We know that a great deal of it is true, and that in many instances the translation is incorrect. But I cannot say what a minister once said to me. I asked him if he believed the Bible, and he replied, “Yes, every word of it.” “You do not believe it all to be the word of God?” “Most assuredly I do.” Well, said I, you can beat me at believing that’s certain … if you believe it all to be the word of God you can go beyond me. I cannot believe it all to be the word of God, but I believe it as it is.[13]

It is apparent from these statements that both Joseph and Brigham understood the term “translation” in quite a wide sense. Robert J. Mathews has aptly summarized this broad understanding of the term “translation”:

Joseph Smith often used the words “translated” and “translation,” not in the narrow sense alone of rendering a text from one language into another, but in the wider senses of “transmission,” having reference to copying, editing, adding to, taking from, rephrasing, and interpreting. This is substantially beyond the usual meaning of “translation.” When he said the Bible was not translated correctly, he not only was referring to the difficulties of rendering the Bible into another language but he was also observing that the manuscripts containing the text of the Bible have suffered at the hands of editors, copyists, and revisionists through centuries of transmission.[14]

This broad understanding of the term “translation” can be seen clearly in the 1843 statement of the prophet: “I believe the Bible as it read when it came from the pen of the original writers. Ignorant translators, careless transcribers, or designing and corrupt priests have committed many errors.”[15]

It is clear that Joseph was not satisfied with the accepted English translation of his day, the KJV. From 1830 until his death in 1844, Joseph would labor, at different periods, on a new translation of the Bible. Indeed, he referred to the “translation of the Scriptures” as “this branch of my calling.”[16] He even claimed divine authority for this endeavor; one of the most clear statements being the revelation he received on 6 May 1838: “And, verily I say unto you, that it is my will that you should hasten to translate my scriptures” (D&C 93:53). On more than one occasion he referred to the German translation as being superior to the KJV. For instance, on 7 April 1844 he said: “I have an old edition of the New Testament in the Latin, Hebrew, German and Greek languages. I have been reading the German, and find it to be the most [nearly] correct translation, and to correspond nearest to the revelations which God has given to me for the last fourteen years.” Later, on 12 May, he would reaffirm this, stating: “The old German translators are the most correct— most honest of any of the translators.”[17]

Brigham Young also realized that the KJV was not free of defects. Indeed, he viewed the translation of the Bible to be an ongoing process: one which should continually receive the input of scholars trained in biblical languages.

Take the Bible just as it reads; and if it be translated incorrectly, and there is a scholar on the earth who professes to be a Christian, and he can translate it any better than King James’s translators did it, he is under obligation to do so, or the curse is upon him. If I understood Greek and Hebrew as some may profess to do, and I knew the Bible was not correctly translated, I should feel myself bound by the law of justice to the inhabitants of the earth to translate that which is incorrect and give it just as it was spoken anciently.[18]

Should the Lord Almighty send an angel to re-write the Bible, it would in many places be very different from what it now is. And I will even venture to say that if the Book of Mormon were now to be re-written in many instances it would materially differ from the present translation.[19]

Other early LDS leaders pointed out defects in the KJV. On 25 June 1893 Charles W. Penrose gave a discourse in which he quoted 2 Timothy 3:16—”All scripture is given by inspiration of God”—from the KJV. He then goes on to say:

But you will find the word “is” in italics. What does that signify? It signifies that the translators, when translating the New Testament, interjected that word to make sense, as they understood it. It is not claimed that the men who translated the Old and New Testaments, in the time of King James, were inspired of God … Suppose we read this passage without that little word: “All scripture given by inspiration of God is profitable for doctrine, for re proof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness.” Don’t you think that would make a good deal better sense? It seems to me that it would. And let me here say, from what we have learned by direct revelation from God to the people in these days, that is the correct rendering.[20]

A few years later Frederic Clift published an article in the church’s Improvement Era entitled, “The King James Translation—A Compromise,” wherein, following an investigation of numerous passages, he concluded that: “The King James translation was the work of fallible men; and I submit, from the instances given, that in some points mistakes were made. We as individuals and as sowers of the word, must therefore follow Tyndale’s advice—go back to the earliest available copies” of biblical manuscripts.[21]

Thus it is clear that for early Mormons the KJV was not considered the final English translation, free of all defects.[22] Outside the LDS church, there were many biblical scholars who shared this sentiment. Indeed, in May 1870 a committee of fifty-four scholars was organized in Great Britain to undertake a revision of the KJV. Later in the year the cooperation of American scholars was sought, and in December 1871 a committee of thirty scholars was formed in the United States.[23] The revisers sought to correct the two main categories of error that Joseph Smith had observed decades earlier: errors of transmission, and errors of translation.

Errors of transmission were of two types: unintentional and intentional. A. T. Robertson conveniently summarized the unintentional type as “errors of the eye, of the ear, of the memory, of the judgment, of the pen, of the speech.”[24] The intentional errors arose because of the sacred nature of the Bible texts. “Where there was any doubt about the original text, since the final text which was going to be read, studied and taken as the rule of faith and life had to be absolutely perfect, corrections were made boldly, things were added and things were omitted, but all was done out of the conviction that it was right to do it, and the purer the intentions the more it was done.”[25] These intentional changes were motivated by historical and geographical difficulties; the desire to harmonize parallel accounts of the same events and sayings; and linguistic, rhetorical, liturgical, and doctrinal considerations.[26]

The resulting difficulty from these errors of transmission is that a multitude of variant readings was produced. On 2 January 1859 Orson Pratt told Latter-day Saints assembled in the tabernacle:

The learned admit that in the manuscripts of the New Testament alone there are no less than one hundred and thirty thousand different readings … How are translators to know which of the manuscripts, if any, contain the true sense? They have no original copies with which to compare them—no standard of correction. No one can tell whether even one verse of either the Old or New Testament conveys the ideas of the original author … How our translators could separate the spurious from the genuine is more than I can tell.[27]

The solution to this difficulty is the discipline known as textual criticism. As the great textual critic A. E. Housman put it, textual criticism “is the science of detecting error in texts and the art of removing it.”[28] Textual criticism has demonstrated that even though there are over 5,000 Greek manuscripts that contain part of the New Testament, they generally preserve four major types of text: Alexandrian, Caesarian, Western, and Byzantine. The vast majority of New Testament manuscripts are of the Byzantine type. This text-type represents a recension of the Greek New Testament carried out in the fourth century A.D. and later. The recension is often attributed to Lucian of Antioch (d. 312), and therefore the resulting text is sometimes referred to as the Syrian text-type.

Broadly speaking, what characterizes this recension is the desire for elegance, ease of comprehension and completeness. It tends to put most of its effort into attaining literary correctness: better balanced sentences, better chosen words: a text, in short, for people of letters. It further displays a studious preoccupation with clarity, for it tries in every way possible to explain difficult passages. Finally, it aims to lose nothing of the sacred text, by freely amalgamating the different readings of a passage. The result is a kind of “plenior” [i.e., full] text, one which is longer but also full of major faults.[29]

It is a text of the Byzantine type that underlies the KJV; this means that many words, phrases, even whole passages have been added to the KJV. These additions, though usually well intentioned, simply were not part of the original, inspired author’s work. Occasionally the additions can be significant. For instance, the last twelve verses of the Gospel of Mark are not found in the most ancient manuscripts.[30] In these verses we read: “And these signs shall follow them that believe; in my name they shall cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; they shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them” (Mark 16:17-18). E. C. Colwell commented on the significance of this error of transmission:

Fanatical cultists in our southeastern mountain regions caress venomous snakes and feed one another doses of poison to prove their faith in the scriptures. But which scriptures? Many ancient New Testaments—among them those generally reputed to be the best—lack the verses on poison-drinking and snake-cuddling altogether. If the citizens of Tennessee and Georgia had chosen these New Testaments, they would not have picked up rattlesnakes and drunk poison, and more of them would be alive today. It makes a difference which New Testament you choose.[31]

Not only is the Byzantine text-type fraught with errors, but the particular edition of the Greek text that underlies the KJV has its own unique problems. In 1881 F. H. A. Scrivener established the version of the Greek New Testament that the translators of King James followed. He used as a primary authority the 1598 edition of Theodore Beza, friend and successor of Calvin at Geneva. He points out: “Beza’s fifth and last text of 1598 was more likely than any other to be in the hands of King James’s revisers, and to be accepted by them as the best standard within their reach. It is moreover found on comparison to agree more closely with the Authorized Version than any other Greek text.”[32] Yet Beza’s edition, and all other early printed editions, ultimately relied on the first published edition of the Greek New Testament, that of the great humanist, Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Erasmus’ first edition of the Greek New Testament was prepared in great haste. The Basle printer Johannes Froben had written to Erasmus on 17 April 1515, requesting his assistance. After arriving in Basle that summer, Erasmus simply sent to Froben as a printer’s copy two manuscripts which were available at a local monastic library: Codex 2e for the Gospels, and 2ap for the Acts and Epistles. He made some alterations to their respective texts based on comparisons with a few other manuscripts (leap, 4ap, 7P). None of these manuscripts contained the Book of Revelation, so Erasmus borrowed a manuscript (lr) from his friend Johannes Reuchlin. Unfortunately, Reuchlin’s manuscript lacked the last six verses, so Erasmus was forced to translate the Latin Vulgate back into Greek. Print ing began on 2 October and was completed in just five months on 1 March 1516. Erasmus himself would later describe this edition as “thrown together rather than edited.”[33]

The great rush to publish the first edition of the Greek New Testament had many unfortunate results. Scrivener observed that with the exception of Codex leap, the manuscripts Erasmus employed “were neither ancient nor particularly valuable, and of Cod.l made but small account.” Erasmus’ retranslation of the Latin Vulgate resulted in readings which are found “in no one known Greek manuscript whatever.” Finally, the number of typographical errors was so great that Scrivener remarked that “Erasmus’ first edition is in that respect the most faulty book I know.”[34] Yet it was this edition, which was available in a cheap and convenient form, that attained a wide circulation and exerted an enormous influence on all subsequent editors. Indeed, later editions of this text became known as the “Textus Receptus,” or commonly received, standard text. The Textus Receptus formed the basis not only of the KJV, but of all the principal Protestant translations of the New Testament in the languages of Europe prior to 1881.[35]

Even after the work of King James’s translators was published, errors of transmission continued. For instance, the originally published “strain out a gnat” (Matt. 23:24) became “strain at a gnat,” and remains uncorrected to this day.[36] Many changes and alterations were made in subsequent editions. In 1851 the Committee on Versions of the American Bible Society, after examining six different editions of the KJV, found about 24,000 variations in the text.[37]

The errors of translation that the revisers sought to correct were also of several types. At the most basic level the problem was the prose employed for the translation. “The language and style of the King James Version were becoming just a little archaic even by the time it was published. The style was sufficiently modern to be plainly understood at the time, yet just old-fashioned enough to carry with it the dignity of the recent past.”[38] Unfortunately, that “recent past” is now almost 400 years ago, and long since forgotten. There have been several efforts to modernize the spelling, punctuation, and forms: most importantly Dr. Thomas Paris at Cambridge in 1762, and Dr. Benjamin Blayney at Oxford in 1769.[39] Yet in 1779 Benjamin Franklin could still lament that the language of the KJV is antiquated, “and the style, being obsolete, and thence less agreeable, is perhaps one reason why the reading of that excellent book is of late so much neglected.”[40]

There are words in the KJV which are no longer used, and therefore convey no meaning whatsoever to the modern reader:

agone, ambassage, amerce, asswage, attent, avouch, bakemeats, bason, beeves, besom, bestead, betimes, bewray, blain, boiled, broided, bruit, but tlership, chambering, chapt, choler, churl, collops, cracknel, cumbrance, daysman, emerods, felloe, flote, foreship, graff, grisled, holpen, hosen, hough, meteyard, minish, neesings, ouches, paps, pate, pressfat, scall, sith, sottish, strawed, suretiship, taber, tabret, tache, teil, trow, undersetter.[41]

Not only are terms such as these confusing, but the reader will have difficulty in finding a source where these terms are defined: the majority do not appear in a standard dictionary such as Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. Often the expressions and syntax are also confusing. Consider the following:

Dead things are formed from under the waters, and the inhabitants thereof (Job 26:5).

The noise thereof sheweth concerning it, the cattle also concerning the vapour (Job 36:33).

The ships of Tarshish did sing of thee in thy market (Ezek. 27:25).

Ye are not straitened in us, but ye are straitened in your own bowels (2 Cor. 6:12).

We do you to wit of the grace of God (2 Cor. 8:1).

Not to boast in another man’s line of things made ready to our hand (2 Cor. 10:16).[42]

Even when a word, or its spelling, is not archaic, the meaning the KJV intended is no longer understood. The “meat offering” in the Old Testament (e.g., Lev. 2) is really a “grain offering”: for “meat” at one time meant food in general, though in today’s speech it only refers to animal flesh. There is potential misunderstanding in the rendering of Matthew 6:34: “Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” Does this mean that we are to make no plans for tomorrow? The rendering of the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)[43] clarifies the intent: “So do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today’s trouble is enough for today.” Another confusing ad monition is 1 Corinthians 10:24: “Let no man seek his own: but every man another’s wealth.” This rendering would appear to promote covetousness due to the archaic use of “wealth.” The RSV clarifies this: “Let no one seek his own good, but the good of his neighbor.”[44] Mark’s report of Herod, Mark 6:20: “For Herod feared John, knowing that he was a just man, and an holy, and observed him” should read “protected him” (NRSV). For the sake of clarity, Paul’s admonition to Timothy: “Lay hands suddenly on no man” (1 Tim. 5:22) should read: “Do not ordain anyone hastily” (NRSV). In James 3:1, “be not many masters” is better rendered: “not many of you should become teachers” (NRSV).

At the next level, there are disagreements in the spelling of proper names of persons between the Old and the New Testaments. Hebrew, Greek, and Latin forms are inconsistently used. Thus we have Kish and Cis; Enoch and Henoch; Noah and Noe; Elisha and Eliseus; Korah and Core; Jonah and Jonas; Hosea and Osee; Elijah and Elias; Isaiah, Esaias, and Esay; Jeremiah, Jeremias, and Jeremie. This lack of uniformity can lead to confusion for the reader. The same problem exists in the names of geographical locations.[45]

On the other hand, the same English word is often used to translate two or more Greek or Hebrew words which convey different meanings. For example, in 1 Corinthians 7:10: “For godly sorrow worketh repentance to salvation not to be repented of,” the words “repentance” and “repent” do not convey the distinction of the two different Greek terms. The RSV translation restores that distinction: “For godly grief produces a repentance that leads to salvation and brings no regret.”

At a more serious level, there are inaccurate translations of the text. Philip Schaff, president of the American company of revisers, explains that for King James’s translators “the more delicate shades of the Greek and Hebrew syntax were unknown,” and “the grammars, dictionaries, and concordances very imperfect. Hence the innumerable arbitrary and capricious violations of the article, tenses, prepositions, and little particles. The impression often forces itself upon the student that they translated from the Latin Vulgate, where there is no article and no aorist, rather than from the Hebrew and Greek.”[46] For example, the love of money is “a root of all kinds of evil,” but not “the” only root (1 Tim. 6:10). The resurrected Jesus’ injunction to Mary Magdalene, “touch me not” (John 20:17), should read “stop holding on to me.”[47]

Paul’s statement in 1 Corinthians 4:3-4, “yea, I judge not mine own self. For I know nothing by myself yet am I not hereby justified,” should read: “I do not even judge myself. I am not aware of anything against myself, but I am not thereby justified” (RSV).[48] Paul’s gratitude in Romans 6:17, “But God be thanked, that ye were the servants of sin: but ye have obeyed from the heart that form of doctrine which was delivered you,” should read: “But thanks be to God that you, having once been slaves of sin, have become obedient from the heart to the form of teaching to which you were entrusted” (NRSV). Peter’s command to the Jews in Jerusalem, Acts 3:19, “Repent ye therefore, and be converted, that your sins may be blotted out, when the times of refreshing shall come from the presence of the Lord,” should read: “Repent therefore, and turn to God so that your sins may be wiped out, so that times of refreshing may come from the presence of the Lord.” Pilate’s verdict concerning Jesus, Luke 23:15, “and lo, nothing worthy of death is done unto him,” should read: “Behold, nothing deserving death has been done by him” (RSV).

The law of tithing is misrepresented in Luke 18:12: “I give tithes of all I possess”; it should read “of all that I get” (RSV). Matthew’s account of Judas’ betrayal, Matthew 26:15, “And they covenanted with him for thirty pieces of silver,” should read “paid him” (RSV). Matthew wants it understood that they paid him on the spot; for he wants to make an allusion to Zechariah 11:12.[49] Jesus’ instructions to his disciples during the last sup per, Matthew 26:27: “Drink ye all of it” does not mean to consume all the wine, but should read: “Drink of it, all of you” (RSV). Following the Pentecost experience, the phrase in Acts 2:6, “Now when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together,” should read “And at this sound” (RSV). The people assembled, not because of rumors, but because they had heard the commotion of the Pentecost event. There is an anachronistic use of the word “Easter” in Acts 12:4. Even Bruce R. McConkie notes that this should be “after the Passover: there was as yet no such thing as an Easter festival.”[50] Paul’s statement in 2 Corinthians 5:21, “For he hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin,” does not mean that we are sinless, but rather: “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin” (RSV). When Paul tells the Galatians: “Ye see how large a letter I have written unto you with mine own hand” (Gal. 6:11), he is not commenting on the size of his epistle, but making a comment about his handwriting. The passage should be rendered: “See with what large letters I am writing to you with my own hand” (RSV).[51]

Given the serious problems of the KJV and the attitudes of early Mor mons, it is perplexing that this translation has become the official translation for English-reading Saints.[52] This change in attitude can in large part be attributed to the efforts of J. Reuben Clark, Jr., and his magnum opus, Why the King James Version. It is ironic, for Clark wrote in his preface:

The most this author may hope for is that his Notes will somehow provoke in some qualified scholars having a proper Gospel background, the desire and determination to go over the manuscripts and furnish us, under the influence and direction of the Holy Ghost, a translation of the New Testament that will give us an accurate translation that shall be pregnant with the great principles of the Restored Gospel. We shall then have a reliable record of the doings and sayings of our Lord and Master Jesus Christ.[53]

It is unfortunate that rather than encourage an accurate translation, “pregnant with the great principles of the Restored Gospel,” Clark’s book has made such an endeavor a notion un-contemplated by LDS scholars. Initially, President David O. McKay had not given Clark permission to publish the book, telling him that “we ought to be a little bit careful about criticizing the Revised Version”; for “the revised text was more accurate than the authorized text in some instances and eliminated the use of con fusing or antiquated English terms.”[54] However, after further debate, President McKay acquiesced and allowed Clark to publish the book.

Clark himself was disappointed with the reception of his book. He wrote to the president of George Washington University: “Contrary to your kindly prediction, I have not had many comments on the book. My own fellow communicants, who are of the scholarly class, concluded (I am sure with one or two exceptions) that I knew nothing of what I was talking about and so paid little attention to the book.”[55]

To some extent this response was justified. Clark acknowledged that “the author’s own scholarship is wholly insufficient to enable him to do any original research in this great field of human thought (which means the author has no standing in that field—and ought to have none).”[56] More importantly, Clark spends most of his book criticizing the Greek text that was used for the Revised Version—a text which was painstakingly established by B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort[57] using sound text critical principles—yet Clark admits that: “It is a little difficult, from materials available to the author, accurately to define or understand the matters and problems involved.”[58]

As a result of this ignorance, the reader of Clark’s book is presented with summarizations and arguments that are false and even contradicted by the very sources quoted in the text. For example, Clark, in attempting to argue for the antiquity of the Byzantine text-type, elicits the support of a fifth-century manuscript, Codex Bezae. The “Codex Bezae type text,” Clark tells us, is “likely of the Byzantine type; if it were otherwise, we should probably have been told.”[59] But Clark had been told by many of the authorities cited in his book that Codex Bezae was the Greek exemplar of the Western text-type. Frederic Kenyon, on page 97 of Clark’s book, tells us: “if it is once recognised that it is not necessary to group in a single family all readings with early attestation which do not belong to the Alexandrian family, it is easy to segregate one group of these which have a common character, and whose attestation is definitely Western. This is the type of text found in Codex Bezae.”

Elsewhere, when discussing the Old Syriac version as contained in the Curetonian (syc) and the Sinaitic (syc) manuscripts, Clark tells us that these Syriac texts “agree rather with the Textus Receptus than the uncials” Vaticanus and Sinaiticus.[60] Once again to the contrary, Kenyon tells us on page 75 of Clark’s book: “we find in the Old Syriac a text including many unquestionably early readings, some of which occur also in the Western group and others in the Neutral (or, as we prefer to call it, Alexandrian [i.e., Vaticanus and Sinaiticus]).” If Clark had consulted the work of the man referred to as “the best authority on the subject,” F. C. Burkitt, he would have learned that “sys is absolutely free from the slightest trace of Antiochian [i.e., Byzantine, from which the Textus Receptus is derived] readings. Not one of the characteristic Antiochian conflations is found in it.”[61]

These points of detail are important, not only for demonstrating Clark’s misunderstanding of matters textual, but for clearly establishing the fact that there are no early witnesses to the Byzantine text-type. The great mass of papyri discovered throughout this century has not altered this state of affairs. As Gordon D. Fee recently observed: “From A.D. 150- 225 we have firm data from all over the ancient world that a variety of text forms were in use, but in all these materials there is not a single illustration of the later Majority (=Byzantine) text as a text form.“[62] The Byzan tine text-type has never been discovered in the early period because it is a recension, the product of critical editing, performed centuries later.

Even when Clark is at his best—for example, in his arguments for the literary supremacy of the KJV—his logic is based on a misunderstanding of the true nature of the Greek New Testament text. He ponders: “Could any language be too great, too elegant, too beautiful, too majestic, too divine-like to record the doings and sayings of Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ?”[63] Apparently the authors who actually wrote down the “doings and sayings” were not so persuaded. As Edgar J. Goodspeed explains: “The New Testament was written not in classical Greek, nor in the ‘biblical’ Greek of the Greek version of the Old Testament, nor even in the literary Greek of its own day, but in the common language of everyday life. This fact has been fully established by the Greek papyrus discoveries and the grammatical researches of the last twenty-five years.”[64] Consequently, Goodspeed argues that the New Testament “calls for a direct, familiar style in translation: an elaborate, elegant style is unsuited to it, and in proportion as it is rendered in a conscious literary style, it is misrepresented to the modern reader.”[65] There are a few modern LDS scholars who are also aware of the uniqueness of the Greek of the New Testament. For example, Philip Barlow has pointed out:

One can hear no King James-like cathedral bells ringing in the background when one reads the Gospel of Mark in koine Greek (the colloquial dialect in which the earliest manuscripts were written). Mark’s writing is raw, fresh, breathless, primitive. The lordly prose of the KJV, especially as it is heard by twentieth-century ears, is for many biblical texts an external imposition, shifting the locus of authority away from the power of the story itself (the “good news”) and toward an authority spawned by the partially artificial holiness suffusing our culturally created notion of “scripture.”[66]

On other aspects of Clark’s arguments Barlow offers a well-reasoned critique and concludes: “Under careful scrutiny then, J. Reuben Clark’s justifications of the King James Bible do not fare well. While the various points of excellence of the Authorized Version ought not to be treated lightly, to insist on it as an official version guarantees significant misunderstanding (or non-understanding) by ordinary Saints.”[67]

It is most unfortunate that the errors and shortcomings of Clark’s study are not more widely known by Latter-day Saints, for there are now available a number of excellent translations[68] of the Bible that far surpass the KJV in both the accuracy of the English rendition, and the establishment of the ancient text underlying the translation. Even if the KJV remains the “official” Bible for English-reading Latter-day Saints, they will do well to consult modern translations to improve their understanding. The efficacy of such an approach has been demonstrated at a popular level by Mark E. Petersen in a little book entitled, As Translated Correctly: “A comparison of the various Bible texts, and particularly of the modern translations, becomes a great corroborative force to the Latter-day Saints, for it places a strong stamp of truthfulness upon the teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, and thus makes the Bible of greater value than ever to the members of this Church.”[69]

In conclusion, the eighth Article of Faith was a bold innovation in the understanding of the biblical text. For Joseph Smith and other early Mormon leaders, the Bible is to be considered “the Word of God” only in so far as it has been correctly translated from an accurately transmitted text. In particular, the KJV, though a magnificent effort, is not to be considered free of defects. Indeed, in the eyes of Joseph Smith it is not even the most ac curate modern-language translation: the German translation (presumably of Martin Luther) owns that distinction.[70] In response to these defects, Joseph Smith labored from 1830 on to effect a revision of the KJV: an effort he considered to be divinely sanctioned, but unfortunately was never to complete.[71] Modern biblical scholarship has strongly supported Joseph Smith’s perceived need for a revision of the KJV. Many scholars have labored to correct both the errors in the English translation and the errors in the transmission of the ancient text that underlie that translation. J. Reuben Clark’s compilation of study notes, published as Why the King James Version, should not be considered a vindication of that version.

Indeed, it should not even be considered a trustworthy summary of the evidence. In the end no translation of the Bible will ever remain entirely satisfactory, for human language itself is constantly changing. As Brigham Young pointed out, even the Book of Mormon, if it were retranslated today, would in many instances differ from the present translation.[72]

[1] B. H. Roberts said of the document: “The combined directness, perspicuity, simplicity and comprehensiveness of this statement of the principles of our religion may be relied upon as strong evidence of a divine inspiration resting upon the Prophet, Joseph Smith” (in Joseph Smith et al., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 7 vols., ed. B. H. Roberts [Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1902-32], 4:535, hereafter HC). And Yale University literary critic Harold Bloom has written: “The Wentworth letter … is marked by the dignity of a simple eloquence, and by the self-possession of a religious innovator who is so secure in the truth of his doctrine that he can state its pith with an almost miraculous economy” (The American Religion [New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992], 82). In 1880 a general conference of the LDS church voted to add the Articles of Faith to its standard works as part of the Pearl of Great Price.

[2] David J. Whittaker, “The ‘Articles of Faith’ in Early Mormon Literature and Thought,” in New Views of Mormon History: A Collection of Essays in Honor of Leonard J. Arrington, ed. Davis Bitton and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 74.

[3] If the Bible is mentioned in the other formulations, it is usually to point out that it does not contain all revelation from God, that the Book of Mormon and other revelations may be expected, and that they too are the Word of God.

[4] An Address by Judge Higbee and Parley P. Pratt …to the Citizens of Washington and to the Public in General, 1, reprinted in Times and Seasons 1 (Mar. 1840): 68-70, and in The Essential Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1996), 69-73.

[5] Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical Notes, 6th ed., 3 vols. (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1919), 3:742.

[6] Gerald Hammond, “English Translations of the Bible,” in The Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. R. Alter and F. Kermode (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1987), 649.

[7] For an excellent discussion of the episode, see Louis C. Zucker, “Joseph Smith as a Student of Hebrew,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3 (Summer 1968): 41-55.

[8] HC, 2:376,391,396.

[9] Ibid., 1:299.

[10] Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F. D. & S. W. Richards, 1855-86), 9:310, here after JD.

[11] HC, 1:245.

[12] Robert J. Matthews, A Plainer Translation: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible, a History and Commentary (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1985), 87.

[13] JD 14:208.

[14] Robert J. Matthews, “Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 5 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 2:764.

[15] HC,6:57.

[16] Ibid., 1:238.

[17] Ibid., 6:307, 364.

[18] JD 14:226-27.

[19] JD 9:311. This notion that the translation of the Bible should continually be updated and corrected was also held by the first English translator of the Greek New Testament, William Tyndale. In the preface to his 1534 translation he wrote: “If any man find faults either with the translation or ought beside … to the same it shall be lawful to translate it themselves and to put what they lust thereto. If I shall perceive either by myself or by the information of other, that ought be escaped me, or might be more plainly translated, I will shortly after, cause it to be mended” (David Daniel, Tyndale’s New Testament [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989], 3).

[20] Millennial Star 55 (1893), 34:544.

[21] Improvement Era 7 (1904): 663.

[22] For a much fuller discussion of early Mormon attitudes toward the Bible, see Philip L. Barlow, Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

[23] The results of the British committee for the New Testament were published in 1881, and the entire Bible in 1885, and are known as the Revised Version; those of the American committee were published in 1901, and are known as the American Standard Version.

[24] A. T. Robertson, An Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1925), 151.

[25] M. J. Lagrange, “Projet de critique textuelle rationelle du Nouveau Testament,” Revue Biblique 42 (1933): 495, quoted in Leon Vaganay, An Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism, 2d ed., English ed. amplified and updated by C.-B. Amphoux and J. Heimerdinger (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 57.

[26] Robertson, Introduction, 156-60; Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2d ed. (Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1968), 195-206.

[27] JD 7:28.

[28] A. E. Housman, “The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism,” in A. E. Housman, Selected Prose, ed. John Carter (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 131.

[29] Vaganay, Introduction, 109.

[30] Both Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus do not contain the ending. Though many Bible translations include these verses, they are agreed to be non-Marcan by the majority of scholars. See the classic discussion in the appendix to B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort, Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek (1881; reprint, Peabody: Henrickson Publishers, 1988), 28-51. For a recent discussion which sees the evidence as not quite so decisive, see William R. Farmer, The Last Twelve Verses of Mark (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1974).

[31] Ernest Cadman Colwell, What Is the Best New Testament? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952), 29-30.

[32] F. H. A. Scrivener, preface to The New Testament in the Original Greek According to the Text Followed in the Authorized Version Together with the Variations Adopted in the Revised Version (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1881), vii-viii.

[33] Quoted in Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1987), 4.

[34] R H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, Eng.: Deighton, Bell and Co., 1883), 430-32.

[35] Metzger, Text, 106.

[36] This error has been recognized by many, including the author of the article on the King James Version in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism (1:110).

[37] Josiah H. Penniman, A Book About the English Bible, 2d ed. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931), 400-401.

[38] Geddes MacGregor, A Literary History of the Bible: From the Middle Ages to the Present Day (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1968), 206-207.

[39] The Oxford edition by Blayney represents the generally current form of the KJV.

[40] Benjamin Franklin, “Proposed New Version of the Bible,” Writings, ed. J. A. Leo Lemay (New York: Library of America, 1987), 935.

[41] Melvin E. Elliott, The Language of the King James Bible (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1967); Ronald Bridges and Luther A. Weigle, The King James Bible Word Book (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1994).

[42] Jack P. Lewis, The English Bible/From KJV to NIV: A History and Evaluation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1981), 54.

[43] The NRSV is a revision of the Revised Standard Version (RSV) of 1952, which is a revision of the American Standard Version of 1901, which, as mentioned above, is a revision of the KJV of 1611.

[44] Joseph Smith also saw this error and similarly corrected “wealth” to “good” in his translation.

[45] Philip Schaff, A Companion to the Greek Testament and English Version, 4th ed. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1894), 362-63.

[46] Ibid., 350.

[47] New American Bible translation; cf. Edwyn Clement Hoskyns, The Fourth Gospel, ed. F. N. Davey (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1954), 544.

[48] Joseph Smith made the same correction in his translation: “For though I know nothing against myself.”

[49] In Zechariah 11:12-13, the prophet receives thirty pieces of silver which he then casts into the treasury of the house of the Lord, just as Judas will do later in Matthew 27:5-6. It is interesting to note that in Zechariah 11:13 there is another KJV error: “cast them to the potter in the house of the LORD” should read: “cast them into the treasury in the house of the LORD” (RSV); cf. A. H. McNeile, The Gospel According to St. Matthew (London: Macmillan, 1915), 408- 409.

[50] Bruce R. McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965-73), 2:117.

[51] Many more examples may be found in Lewis, The English Bible, 35-68; Alexander Roberts, Companion to the Revised Version of the New Testament (New York: Cassell, Petter, Gal pin, 1881), 75-153; and J. B. Lightfoot, On a Fresh Revision of the English New Testament, 3rd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1891).

[52] “The First Presidency Statement on the King James Version of the Bible,” Ensign 22 (Aug. 1992): 79.

[53] J. Reuben Clark, Jr., Why the King James Version (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1956), viii-ix.

[54] J. Reuben Clark, Jr., Office Diary, 26 Jan. 1956, in D. Michael Quinn, J. Reuben Clark: The Church Years (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1983), 177.

[55] J. Reuben Clark, Jr., to Cloyd H. Marvin, 10 Mar. 1958, in Quinn, J. Reuben Clark, 177.

[56] Clark, Why, 21.

[57] “While the work of revision was going on, Westcott and Hort were engaged simultaneously on their epoch-making edition of the Greek Testament, which appeared five days before the Revised New Testament. They placed their critical work at the disposal of their col leagues on the revision company, and to a very large degree their findings on the text were approved by the majority” (F. F. Bruce, History of the Bible in English [New York: Oxford University Press, 1978], 139).

[58] Clark, Why, 288.

[59] Ibid., 224.

[60] Ibid., 72.

[61] F. C. Burkitt, “Text and Versions,” in Encyclopaedia Biblica, ed. T. K. Cheyne and J. S. Black, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1903), 4:4,987. See also Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford, Eng.: Clarendon Press, 1977), 36-48, esp. 43.

[62] Gordon D. Fee, “The Majority Text and the Original Text of the New Testament,” in Eldon Jay Epp and Gordon D. Fee, eds., Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1993), 186.

[63] Clark, Why, 355.

[64] Edgar J. Goodspeed, preface to The New Testament: An American Translation (Chica go: University of Chicago Press, 1923), v.

[65] Quoted in Clark, Why, 355. In matter of principle, the First Presidency and Council of the Twelve would appear to agree. They have written: “Only translations which very precisely reproduce the words, phrases, and sentence constructions, as well as the expressions and style of the author of the original, can transmit impartially the sense of what the Lord revealed in the language of the original… The translation must contain the recurring expressions and also awkward sentence constructions. No attempt may be made to paraphrase in an explanatory way, to make alterations, or indeed to improve the literary ability and knowledge as expressed in the current English text versions” (“Guidelines for Translation of the Standard Works,” First Presidency and Council of the Twelve, 17 Apr. 1980, in Marcellus S. Snow, “The Challenge of Theological Translation: New German Versions of the Standard Works,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 17 [Summer 1984]: 136).

[66] Philip L. Barlow, “Wanted: Mormon Theologians. No Pay, Great Benefits,” Sunstone 16 (Nov. 1993): 35.

[67] Philip L. Barlow, “Why the King James Version?: From the Common to the Official Bible of Mormonism,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 22 (Summer 1989): 36.

[68] Four excellent translations, the New Revised Standard Version, Revised English Bible, New American Bible, and New Jerusalem Bible, are now available in one convenient volume: The Complete Parallel Bible (Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1993).

[69] Mark E. Petersen, As Translated Correctly (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1966), 70.

[70] See n17, above.

[71] A portion of Joseph’s translation of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew has been included in the Pearl of Great Price under the titles “Selections from the Book of Moses” and “Joseph Smith-Matthew.”

[72] JD 9:311.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue