Articles/Essays – Volume 32, No. 3

bash | Neil LaBute, bash: latterday plays

The last time we saw Mormons prominently featured on the New York stage was in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, where an orgasm-inducing female Angel Moroni crashed (literally) through an apartment ceiling and radicalized an AIDS-infected gay man into a millennial prophet.

In Neil LaBute’s recent Off-Broadway hit bash: latterday plays, Mormons (and Mormonism) were not half so over-the-top as Kushner’s wild creations, which were inserted by the playwright for theatrical effect and as a comment on LDS homophobia. Instead, the Latter-day Saints in bash re veal Mormon character as it crystallizes like sugar along narrative lines of devastating proportions.

Happily, bash has bigger fish to fry than just making sure we get our quota this year of the ever-growing member ship of America’s most successful indigenous religion. LaBute, who recently was the bad boy of BYU’s theatre and film department where he was engaged in a Ph.D. program, is by no means a provincial Mormon play wright. He is most noted for crushingly dark films, In the Company of Men and Your Friends and Neighbors, where nary a Mormon is seen nor heard of.

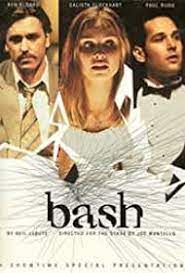

Like Euripides and other Greek playwrights, LaBute is tackling big themes, specifically evil, albeit in the relatively quiet, plebeian lives of four modern Americans. Two of those char acters were played in the first and third one-acts by Calista Flockhart of TV’s Ally McBeal, undoubtedly one of the reasons why this riveting, scorching show (in a limited run through July 25 this past summer) enjoyed enormous popularity.

All of the characters in bash find that telling their story is tantamount to their survival, a motivating factor in Mr. LaBute’s films as well. It’s as if reality is only in the telling, and the telling burnishes their lives into understanding, into absolution, into justification, and perhaps into meaning.

The woman in the police station indicates to the unseen inquisitors that the tape in the recorder is about to run out. It’s as if she must have a permanent record of her story, which makes up her life, not unlike the tragic heroes of Greek drama. It’s not an unusual story, she says at one point, except that it happened to her.

More than just “holding the torch” for the father of her son, this woman is caught in a deadly cocktail of garden variety, adolescent fantasy and Greek cosmology on a poignantly elementary level. Again and again she struggles to remember the Greek word which de notes how humanity through its mortal nature has thrown the whole earth off its axis. And when she’d learned by chance in a high school office of her lover’s hasty exit, she was, she explains, “frozen in time. All I could hear was the universe. The cosmos was laughin’ down at me.”

What’s touching about this woman is that she is a simple person filled with street talk. Ms. Flockhart was able miraculously to appear as both a tower of complicated desire and a mall traipsing ditz at the same time. The result was that her strung-out and beaten-in character had the dignity of a tragic figure, alternately addled and oddly calm, eventually exploding into blood-curdling screams right out of Oedipus Rex.

In Iphegenia in Orem, a Mormon executive finds that he must tell his story, involving the death of his infant daughter, even if it’s to a stranger. Or perhaps because it’s to a stranger. “I can’t tell anyone at church,” he explains to a woman sitting across from him in his hotel room, “or the police. So I chose you. I walked through the lobby and I just chose you.”

Ron Eldard played with cheesy affability the middle-aged Orem resident who finds the trappings of his office life (the fax machines whirring, the hustle and bustle) almost to be an aphrodisiac. And, in fact, Eldard got several laughs through his ethnic Mormon boyish tics and his creepy naivete that somehow seemed calculated. When the character is threatened with being downsized out of the firm, he becomes energized, spinning, as it were, into an ancient Mediterranean world of fate.

This middle executive, who goofily references old movies like Alfie and Kramer vs. Kramer, makes a huge Mormon point of the fact that he doesn’t drink and doesn’t swear. And yet ultimately, he reveals a twisted justification, perhaps more Faustian than Greek, for a deed so dastardly that the audience audibly gasps.

In A Gaggle of Saints, we get LaBute’s signature, David Mamet-in spired cross talk even though the piece is actually two interlaced monologues of a college couple about to be engaged. Theirs is a tale of a “bash” or party, which they and a few other couples from neighboring wards upstate attend in Manhattan-a prom of sorts, glitzed and tuxedoed-out. John, a returned missionary and the son of a bishop who likes to give his son un wanted haircuts, was played by Paul Rudd who was all brash and bravado, a young lion still entranced with his own roar. Watching him talk about how he met Sue (Ms. Flockhart stunningly dressed in a black taffeta gown) as well as about his friends and myriad exploits was like watching an athletic event of sorts—in a tux. Both he and Sue were instantly likable by sheer virtue of unabashed youthful charm. “He’s cute, nice body, and I didn’t know him” recounts Sue when she first spies John on the school outdoor track.

But at the plush Plaza Hotel, which Sue describes dreamily as “a wedding cake someone left out there on the corner” opposite Central Park, the “gaggle” of Latter-day Saints can not hold onto the picture-perfect night of their dreams (literally punctuated from time to time by the clash and flash of a photo shoot on the actors’ still selves). John, it seems, can’t seem to get over the sight of two gay men being affectionate with one another in the park, one of whom reminds him of his father. So it is later, after the dance, while the girls rest in the hotel room the group has rented as a crash pad for the night out, that the boys go for a walk in the park. When John recognizes one of the men from earlier, he follows him into a public bathroom while his friends wait just outside and the word “bash” eventually takes on a different meaning.

Evil in this one act is first made to make us laugh, to collectively luxuriate in the memory of our own youthful ardor, all dressed up in formal attire. It is an evil embodied in a passing “ad venture,” in young men “giggling like school boys” as they clatter back to the hotel. It is an evil in which a ring is stolen from a broken body on a concrete lavatory floor, in which a vial of Mormon consecrated oil is mockingly poured on a now soft and bloody head, a so-called “elder” crooning a “blessing” in the coup de grace of this priesthood posse-turned animal.

“I know the scriptures,” states John, in a tone deadly serious. “And come on! It’s [homosexuality is] wrong!”

The evil portrayed in “bash” is so brackish, so jolting in its revelation that Mr. LaBute leaves us wondering how it could ever happen. And like Sue, back in the hotel room with the other primping and simpering girls, we are also left questioning how any of us could decide not to know in order to keep the evening, the relationship, the life, whatever, so perfect. “It was a perfect night,” she tells us, while fingering the gold ring Joe presented her in front of the others at breakfast.

Mormons are sometimes referred to as “Super Americans” because of their accommodation en extremis to “traditional” American ways and mores. LaBute has done what Angels in America did a few years ago—that is, posited Mormons into the conversation which the rest of the world is already privy to. But the bad boy playwright from Provo also seems to have created Latter-day Saints whose stories (even as they tell them) are far from the rosy, family-centered picture we get elsewhere—from 50 East North Temple to Time Magazine to Barbara Walters. What vaults evil into institutional, arguably cosmic dimensions is not that one is capable of it, but the wholesale denial of our capacity to do evil.

bash: latterday plays at the Douglas Fair banks Theatre, New York City, NY, Summer 1999

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue