Articles/Essays – Volume 36, No. 2

Body Blue: Excerpts from a Novoir

To write is to siphon the clouds, the stars, the wind and rain through the pen. It’s like holding a root into the earth of the soul. It’s like a channel from the sun to the paper. Hold the pen with love and all these things.

Prologue

When the blues come knockin’, you better open up your door.

—Little Milton

My father’s father’s father, a good Mormon man, hanged himself in the garage.

My father’s mother, a good Mormon woman, spent a year in the Nevada State Mental Hospital after giving birth to six children and being bounced around the West by a husband who couldn’t keep a job. They sampled many homes and gardens: Brigham City, Logan, Salt Lake City, and Price in Utah; San Diego in California; Ely, Ruth, Boulder City in Nevada; Malad and who knows where else in Idaho. The fact that she was a gypsy by situation rather than nature and the fact that her husband had an on-again, off-again obsession with alcohol must have gotten to her after a while. The family story goes that after one year in the hospital in Sparks, Nevada, the powers-that-be telephoned her sister, Helen. “Please,” they said, “Come and take Hortense home. Nothing’s wrong with her, except she’s dying of a broken heart.” One could say that Hortense’s life failed her or that she failed her life. One could say she suffered from melancholia, if one is inclined to put life into neatly labeled boxes.

My father decided to finish his life on a different planet without moving there. At age sixty-five, he had a nervous breakdown, had to be subdued and was taken to the hospital for a week. “But he wasn’t talking about Martians or anything like that,” a cousin said. “He was just telling everybody things he hadn’t been able to say for years.” For twenty years after that, my father listened to his own tune, strictly his own. If anyone scolded or told him to mind his manners, he began singing loudly, “Blow the Man Down,” or some such dismissive tune. He was free at last, some of us thought. Free from the rules, the shoulds, the oughts. One could say he suffered from senile dementia, if one is inclined to have comforting, compartmental answers.

So where do these blues come from? This depression? This melancholy? From the Scandinavian ancestors who didn’t get enough light in winter because of the Midnight Sun and overcast skies? From the Welsh forefathers who were known to have a few loose branches in their family tree? From the downtrodden? From generic human angst?

To talk about depression, melancholia, the blues, any of those things, it seems that the people who need to categorize don’t think in terms of the ocean, of the witnessing of the waves that pull away from the shore, then rush towards it and curl and roll and crash and then pull together again. Endless motion. Endless breaking. Endless knitting back together. The ocean. The waves. Endless cycling. The turn of a wheel.

Chapter One

Woke up this mornin’.

Had a story on my mind.

Woke up this morning’,

A sad story on my mind.

Trouble is. . .

Trouble is. . .

Sometimes in a life, it’s like you fall down an invisible shaft, one you didn’t see coming. You sail to the bottom. Land on your back. When you come to, the day is blacker than night, the sun has a new name, your hands and face are strangers. Bilge water rises around you. You can’t last. The idea of stillness sounds good, even while your body is picking you up, walking you into the kitchen, to daylight, to change. Your padded slippers scuff the tile floor. Birds sing outside. But who cares on a blue Monday when the blues knocks at your door, pushes past the lock and says, What’s up? as it sits on a big overstuffed sofa on its ample backside.

Trouble is, can a girl like you sing the blues? A girl who’s supposed to be sunny, cheerful and greet the day with a song? A girl who’s expected to be dignified and classy? A girl with promise, talent, looks, brains, and blessings on her head? Yet a girl whose feelings speak out all over her face and who cries in public. A girl with dark moods that feellike tunnels. A girl who’s much more ragged than refined. Believe me, I know blues. Honey, I get the blues, yes I do.

The Life.

I speak of my life in the present tense. It is always with me. Always reminding me that it’s still with me. Encased in the labyrinth of memory.

I’m five years old. My father tells me he has a bicycle for me. It’s a beat-up bicycle, but one that works. He’s painted it a dull black to give it a newness; its fenders are dented; it has large balloon tires; it’s a girl’s bike and when I get ready to ride, I stand between the pedals, not quite able to reach the seat.

My father holds me as I stand on the pedals. I tell him to let go. I can do this. I know I can do it. Freeze frame: the bulky black bicycle, my father holding the handlebars, me ready to go, that moment like a commemorative stamp in the story of my life. He steadies me on the first few rounds of pedaling, and then, I take off, just like that. Thin, shy me, pumping away down Fifth Street in Boulder City, Nevada, off into the sunshine, into the possibility of turning those wheels forever until I reach infinity. Always fascinated with infinity, even doodling infinity symbols on my papers at school.

When my feet turn those wheels on my new/old black and dented bicycle, I sense I can ride down the street into something much more ex citing than ordinary life. The pedals spin around and around until they become something more than pedals with a chain. My bike is Pegasus headed for the summit of Olympus, headed for divinity, and I’m not human anymore.

But why does my life seem so small to me, even at the age of five? What makes me want so much more? Who is this greedy self that dreams of wheels turning and rolling into larger territory, wheels that make promises as they turn? Who is this person who wants to be bigger than everything around her, who wants to be everywhere she isn’t?

Forty-eight years later, on the twenty-ninth day of April, my friend C. J. and I close up her apartment in Fort Collins and head out of town on Highway 14. Me on top of a black cherry Cannondale road bike with Blackburn racks, a Northface two-person tent tucked away in Jandd panniers, Pearl Izumi bike pants, Shimano clip-in shoes, a Giro bike helmet, Patagonia vest and a long-sleeved shirt. She on top of a spring green bi cycle custom-designed by Albert Eisentrout, an eccentric fellow in Colorado Springs. It is a love bike with heart-shaped tubing, a gift from her soon to be ex-husband who’s a bike enthusiast and knows about state-of the-art equipment. We are gear queens ready to burn up the road. It’s a long, straight road into the farmlands of eastern Colorado. Pretty blank, pretty uneventful with acres and acres of newly-planted crops barely showing tips of green. But we’re on our way across America, the United States of America. I need clarity in all the smoke and indecision of my life. I need to find a way back to my aliveness. So does C. J.

In this particular year, I’m less enchanted with infinity, not having been able to make the finite work very well. The perimeters of my world have turned inhospitable. Marriage has failed; separation isn’t better. Thirty-two years of a Mormon temple marriage and a wannabe Happy Family/Smiley Face marriage up in smoke. Divorce is imminent. My husband David and I hadn’t made it to “united we stand.”[1] We weren’t moving in the same direction. Our promises of faithfulness for time and all eternity were a bust. I was also a bust at motherhood because my sons were independent-minded, irreverent, raucous, and uncontrollable, and my first son, Geoffrey, had disappeared on me when I wasn’t watching. Evaporated. Died much too young before we had a chance to get fully acquainted.

I’m bone-tired of the fiction of myself, of the mask of the kind, elegant, noteworthy, nice woman I’ve tried so hard to be. Everything feels out of kilter, strange, topsy turvy. I feel like a long, extended row of ze roes. Unrecognizable. Uncomputable.

My friend C. J., all around outdoors woman and also my student in the Vermont College MFA in Writing Program, needs to run from the Rockies as much as I do. We’re both getting divorces. We’re both at loose ends. We both need to do something to jolt us out of our sense of being abandoned by love and its promises. We’re the perfect match to do something indescribably insane, like me agreeing to C. J.’s cockamamie plan to take a 2,300 mile trans-continental bike ride from the Front Range of the Continental Divide to Montpelier, Vermont, for the summer residency. We’ll ride fifty-five miles a day with no time scheduled for days off. We’ll carry forty pounds of gear and have no support vehicles. We’ll camp out every night. And all of this during tornado season in the Midwest.

It doesn’t matter that I haven’t ridden my bike seriously for years, if ever, that I’ve only trained for two months on flat terrain, that I hate hills. It doesn’t matter that C.J. is sixteen years younger, much more fit, a much more likely candidate to complete such a trip. It only matters that both of us want to get out of Dodge and fast. Escape our lives. Escape everything.

So, two days before May Day, the time of flowers blooming after April showers, we straddle our bicycles, both feet on the ground and grin at each other.

“America, here we come,” C. J. shouts, a strand of hair already loose from underneath her helmet and blowing across her face. “Yes, yes and yes.”

From Inside my Head.

It’s like this: when a big event comes along, the U.S. Postal Service commemorates the moment, the notable place, the triumph, the kiss, the breakthrough. These memories are set by engravers making incisions in metal, but that’s beside the point.

There’s a commemorative stamp lying on your desk right now, and you love commemorative stamps. This one is the Centennial Olympic stamp—1896 to 1996—the almost naked man preparing to hurl the discus. His arm is pulled back. He’s poised for action. He’s the essence of the Olympic Games. The embodiment of Hero. But he’s a concept, not a man.

You don’t have a story here, do you? Only a hero in his perfection. What would you find out if you saw other pictures of this man, such as him stepping out of the bath? Is he as well hung as the rest of his body promises? Is he really a winner? Is he a good man when he’s not hurling the discus? Or is he boorish and cruel to women and children? What face does he wear when he’s not in front of a crowd?

Too bad there’s not a series of stamps, like moving picture stamps, where you could watch him preparing for the big event, making his way to the stadium through rude crowds, swinging his arm from back to front and releasing the round disc to spin through the air. It could show the perspiration on his neck before the discus sailed across the stadium, flecked with pieces of sunlight as it spun, tilting slightly, wobbling, land ing where it could be measured. And then you could see the crowd cheering and the wreath of laurels being placed on his head. Or not.

But postage stamps wouldn’t be postage stamps if they were like that. They’re one picture that implies history. Period.

You’re attached to stamps and monuments. More than that, you in sist on commemorating the harsh moments, the unforgivable things said or done—those things hovering in the shadows where low-burning lanterns give off greasy light and blacken the walls with smoke. You have embraced, carried, and nursed those bruised memories until they have almost destroyed the rest of you. But why is it necessary to commemorate the ugliest parts of yourself and tuck them deep inside where they fossilize like trilobites on a dry lake bed? Why should you, a living person, become a statue of stone, an unchanging, granite-carved monument of memory that may have nothing to do with truth? What about the blanks, the continuum, the margins, the rest of the story? Isn’t there forgiveness? Or only the harsh remembrance of things you didn’t mean to do? Freeze frames. Cold. Icy. Unforgiving.

The Life.

Death is as big as life, maybe bigger, but nobody wants it coming down their street. As if talking could keep it out of town. . . .Most people shift their eyes when the subject slips out. It’s unsocial. It’s gauche. Un comfortable.

Geoffrey died. My first child. Our young son. Sometimes I want to talk about the Geoffrey I loved with all my heart and feared with all my fear and about what happened to him, but it makes people uncomfortable. Their alarms go off when The Nice Talk Rules are broken. They squirm and say they have someone they must talk to, so excuse them, they’re oh, so sorry to have to leave. It’s best to stay with innocent, uncomplicated sorrow. Let people cry for the dead. Let nothing ruffle pure grief.

It’s May of 1970, and David and I are standing in a hushed room of a chapel with sage green carpet. Friends and relatives are loosely assorted around an open casket, while we shake hands with a flow of blurred people.

“I know just how you feel,” a woman with a tightly curved nose says to me. “I lost a son, too.” She pats my hand and curls her bony hands around my cold fingers. “God needs your child now,” she says. “It’s his time to go.” Mrs. Hansen seems sure of her theology, but I want her to go away. The wax of my friendly-face smile feels tight. “Nice of you to drop by,” I say.

The line winds like the wall of China as people dressed in silk and suits wait to express regret in the dim light fanning from the wall sconces. Curious people who’ve taken time from their daily routine to pause and honor the dead, so many who haven’t known, who say they had no idea.

We hadn’t advertised Geoffrey’s hemophilia when we moved to Salt Lake City. Everyone seemed to back away at the mention of the word. The royal disease. The rare blood disease. We’d learned to be selective about whom we told. We knew that superstitious fear bred unconscious cruelty.

Even I was afraid of what had come through me—something so out of the ordinary that no one in the family had ever had before. And on this day in that seafoam colored room, I am a publick example, standing before the mourners in moss green, a woman needing comfort, but also a woman who’s played a part in passing on a thing called hemophilia. I am a link in something I didn’t know I was linked to. Me—the carrier. Someone dropped a drop of madjack potion into the amniotic fluid. Or maybe I did something wrong along the way—something major I hadn’t owned up to.

“God will watch over your child now.” Mrs. Hansen is speaking to David, whose gray crescent smudges beneath his eyes seem darker because of his navy blue suit and tie. “It’s better this way. God’s plan is big ger than we can know.”

Am I really standing in a reception line at my son’s funeral—my black hair limp and disinterested in holding a curl, my face unlit by enthusiasm? The day seems diffuse, not of one piece, separated into particles that form clouds to hide the sun and the way out of this confusion.

“Thank you, Mrs. Hansen. Thank you for coming today.” David seems simpler in his acceptance of her sympathy. He weeps openly as she squeezes his hand. I’m only feeling cold and hostile hearing her platitudes and feeling her fingers curl around mine. He’s a simpler man than I’m a simple woman. He’s still holding her hand.

In the blur of the next hand grasping mine, the next mouth offering condolences, I overhear a gathering of relatives talking to each other— the in-laws to the out-laws, depending where one fits into the hybrid family tree David and I had joined together by marriage—a group of people bunched tightly and unaware of anyone else around them.

“This didn’t come from our side of the family,” someone says from the cluster of all-my-relations. Battle lines are being drawn. “We’ve never had anything like this ever. Hemophilia is not in our bloodline.”

“Well, it didn’t come from our family either,” another definitive voice says as the soft light of the hushed room fails to soften the words. “Never heard of it before now, except in books.”

David and Phyllis, X and Y, my husband and I. Two young parents standing in a room full of people shaking their heads and the responsibility from themselves. Looking uncomfortably at the casket. We have failed genetic engineering. Mis-manufactured the blood. Marred the family myth of perfection. But why should blood misbehave for any family? Why has the blood turned on us? Against the child lying in a nest of blue satin pleats with powdered, rouged cheeks and a faint touch of lipstick on his lips?

Everything is turning, it seems. Turning strange. My autonomic body has secrets it’s kept from me, things like physical changes in chromosome relations, biochemical changes in the codons that make up the genes. Mutations. Changes in the lineal order of the ordered. Accidents. Surprises. And, my emotional body is more complex then I’d imagined—pride and wounded pride, shame, anger, motherly love for the flesh is suing forth from my body and frustration at being asked to carry this burden. All this behind my friendly face.

From Inside my Head.

Is this what two people get when they made love, when they had sex, when they obeyed nature’s imperative: let’s get together, yeah, yeah, yeah? Hot to trot and what have you got? A little boy whose blood won’t clot. Now we stand like two Jobs in the middle of the desert. Why me, God? Why us?

“Be grateful you have other children,” Mrs. Hansen is saying. “Life does go on, so be grateful for everything it gives you, even the difficult things. Only you can lay your suffering at the feet of God.”

Mrs. Hansen’s words make me more tired than I am. Is she a book on the subject or something? Does she understand subtlety and complexity, the condition that every case in court has different facts? I want my own grief. And why should she be so sure of herself? Why is David still holding her hand like she’s his mother and why don’t his tears stop rolling down his face?

I want to capture my life in words and pin it all down somehow. I want to capture the essence of who I’ve been, who I’ve wanted to be, who I seem to be after all the trying to be other than who I am. I have a story to tell. I confess.

The truth is, no one can capture an entire life. For everything selected from a life, a thousand other things are left out. For everything told, there’s the question of interpretation. Maybe there’s no such thing as the whole truth and nothing but the truth. When we shape the past in the present, the past becomes something new. When we pin a butterfly to the corkboard, we no longer have the flittiness, airiness, the magnificence of what a butterfly is.

I’m a musician who believes music speaks more clearly than all other mediums. Sometimes, my speaking needs to be singing. Sometimes I need to hear the beauty of a melody line or the wail of an honestly-felt song.

Chapter Two

I thought of that while riding my bike.

—Albert Einstein on the Theory of Relativity

Two Weeks before the Journey

“Is this some kind of mid-life or post-divorce crisis?” my mother asked in her ancient, wavering voice over the telephone. She had a hiatal hernia somewhere in her voice box. I could picture her sitting in her Lazy-Boy chair, her old-age shoulders sloping too much and her head too high off her neck, but I could still envision her signature elegance. “That’s pretty ambitious, I’d say.”

I could imagine her expression, the one that mothers reserve for their hopeless offspring who are about to set off on a wildhair adventure. “You’re strong, but not that strong,” she said. “You’re fifty-three years old. And aren’t you supposed to train on a bicycle for months and months to be in shape for this kind of thing?” She sipped something, probably water or juice between words. “Why do you have to do this?”

“Mom, skip the drugstore psychology.”

“You don’t have to be snippy. Remember what your dad said about pride.”

“Of course: the story about Prince Bellerophon riding to Mt. Olympus on Pegasus. He thought he’d become Zeus. Hubris a te nemesis. I’ve heard it all before, Mother, and you’re barking up the wrong tree. Under stand? This isn’t about my pride.”

“But everybody can see you’re hurting. What’s so bad about that? Just accept the fact of hurting for a while and then come back and live with the rest of the human race. That’s how it works.”

“I need to do something I’ve never done before, okay? It’s crazy. It doesn’t make sense, but I’m going to do it. Period.”

“You always were impulsive.”

“That information is useless, Mother. Doesn’t do anyone any good.”

“Are you taking a cell phone?”

“No.”

“What about anything for self-defense?”

“I took one self-defense class; that should be sufficient.”

“I heard about a man on a long bicycle trip who got kidney stones from being on his bike so much.”

“Mother!”

“You always were the strongheaded one, weren’t you?”

“Nothing matters. Can you understand that nothing matters to me right now. I hate this gray place where nothing matters.”

“But there are better options than riding a puny little bicycle across the country. What about your joints? You’re not a spring chicken, you know. You could seriously damage your body. Did you ever think to compute just how many spins of the pedals it will take to get you from here to Vermont? Think about it. And what about your boys?”

“They don’t need me anymore. You know that.”

“So they might say. Why don’t you make an appointment with a therapist?”

“I just need to do something wild and reckless. I want to take care of things myself. Can you understand?”

My mother took a huge sigh from the eons of her experience. “Where’s your sense of humor? You’ve gone dry as a bone. Can’t you laugh at yourself anymore?”

“You’re right, always right, Mother, but I don’t feel like laughing, period, that’s the way it is.”

“Just laugh, Phyllis. Start now.”

“Yeah, yeah, like Daddy used to say: A merry heart doeth good like unto medicine.’ I’ve had it with the scriptures, Norman Vincent Peales, and drugstore analysts.” I started shuffling papers on my desk. I didn’t want to talk any more. “Anything else before I’m off? Any other words of encouragement?”

“No, Miss Temperamental. Why are you in such a hurry?”

“Trust me, Mom. I’ll call you from somewhere in the Midwest.”

“You and Dorothy and her red sequined shoes. The people who care about you are more real than those shoes, believe me.”

“Me and Dorothy. Blown away from home. Gotta get to Kansas, Mother.”

“You don’t need to run away, Phyllis, but if that’s what you want to do, then good luck. God will help if you’ll humble yourself, but I know you don’t like me to talk about God or the church.”

“Mother.”

From Inside my Head.

Singin’ the blues is all about letting it all hang out. Not pretending. You could pretend you’re not singing about what happened to you, just talkin’ about somebody out there somewhere, but you know and I know, you gotta know it to sing it.

You used to be happy and you used to love to dance, sing, and whirl around. But somewhere along the way, you got all sad and choked up, maybe about the time you concluded the final straw had been laid across your back. Your pores oozed the blues. Your mind clogged up like wet spaghetti. You felt like singin’ the blues more than anything else. And you knew you had to do something, even if it was get on your bicycle, girl. Roll those wheels. Flush the sad out of your cells and bring them back to life.

The Life.

Maybe it’s a dream and maybe it isn’t.

My husband licks the small of my back while I sleep, caressing my hips while I try to escape the waking world. His tongue wet and sloppy on my skin, I suddenly pull myself to the edge of the bed. This is my husband, and I’m crawling away from him, inching away, a bit at a time.

Love. What is love? And sex, what is that? It means too many things, I think. It’s a place for abandon and recklessness and giving up your mind, and yet all I can think about when he touches me is that I don’t want to give in to that touch. I don’t want him arousing me anymore. I’ve given over one too many times. I roll out of the covers and run to the bathroom to gasp for air. I feel six years old. The tightness in my chest won’t open up.

He follows me. He stands behind me and cups his hand around my breast. “You want me. Don’t try to run away.” My autonomic responses are waking, my genetic impulse to procreate is in action, and I find myself trembling at the touch of his fingers on my nipple.

“It’s a lie between you and me,” I force myself to say, resting the palms of my hands on the sink tile. “Things dried up a long time ago. You want other women, so go take them. Go have what you want, but don’t drag me along just so you can have everything you started with. I don’t want you. I don’t want your body. Leave me alone.”

He presses his maleness against my back side, and I feel goose flesh on my arms. “Just because I’m attracted to other women doesn’t mean I don’t love you.”

Why can’t I be calm? Why can’t I be cool? Why can’t I tell him to go away and leave me alone? I feel excitement rising in my body, that sap, that juice, whatever it is that is the source of all fluids.

“Go find someone else. Things are too messy between us. Too many botched attempts. We don’t have a big enough heavy-duty pink eraser, you know. ”

He bites into my neck and plants three tiny kisses on the lobe of my ear. “I want you,” he says. “I’ve always wanted you.”

“That’s not enough anymore,” I say, reaching for my bathrobe on the hook of the bathroom door. “Like I said, things are too messy. We’ve blown it too many times. I just want a clean slate.”

I break free of his hold and direct my arms through the purple sleeves of my robe. Tie the sash in front. Hoist myself up to the bathroom counter. Let my legs hang over the edge. Swing my legs and hum a faintly familiar tune.

“There’s not a clean slate anywhere in this world, except for a brand new baby. Fact is, people make mistakes. But smart ones forgive themselves and move on.”

“All I can feel right now is that the mistakes are always there. White correcting fluid still lumpy. Erase marks.”

“But isn’t there such a thing as forgiveness?” He examines the shadow of his beard in the morning light. “For a woman who talks about faith, you don’t have much.”

He looks small in his nakedness. His family jewels are at rest, unengorged, hanging quietly. He is a man. No more. No less. A simple man with a penis, pelvis, a hairy chest, arms, legs, and a head and whatever else.

“Actually, the way I figure it,” I say from my perch on the counter, “if you hang onto the bad things that happen, you’ll have something to talk about. Something dramatic. People love a shocking story. A whispered, closely-told shocker. They try to hide their fascination with your bad luck or judgment while secretly congratulating themselves on their lot in life being better than yours. Or they feel hip and privileged being around someone who’s been there, done that, and knows all about bad luck. Don’t you think?”

“You’ll never be happy. You don’t want to be happy. You’re too attached to the sad, cynical story of it all.” He pulls a T-shirt out of a bathroom drawer and climbs into it. Then he pulls out his running shorts. “I couldn’t make you happy if I tried, and believe me, I’ve tried. When are you going to lighten up?”

“Iron Maiden. Adagio Alice. Pavanes for dead princesses. That’s my style.” I smile against my will and force a laugh. And then the forced laugh turns into a real one. He rolls his eyes back, slips his sweatband onto his forehead, and kisses my cheek quickly. The bathroom brightens.

Too much stuff gone down, baby,

Too much stuff.

Too much acid in my heart,

Too much.

Too many lovers, too many lies,

No more desire, between my thighs.

Too much stuff gone down, baby,

Too much stuff.

Too much broken glass,

Too much.

Don’t touch my body, don’t touch my breath,

My face is empty. No kisses left.

Cars are all right on occasion, but they are not moments of grace as bicycles are.

—Colman McCarthy

The Journey.

C. J. and I started our bicycle journey on the morning of April 29, 1996. We left Ft. Collins, Colorado, heading east to Montpelier, Vermont, where we planned to arrive in seven weeks to attend the summer residency at Vermont College. We’d outfitted ourselves for wind, rain, cold, heat, emergencies, and the night. All of this, weighing about eighty pounds, was stuffed and rolled into a gazillion plastic bags and fitted into front and back panniers on both of our bikes. The weather looked promising enough on the day we began, pedaling out of town on Vine Street to Highway 14 into farm and ranch country and America here we come.

As we passed over the interstate, jazzed to be on our trip at last, we knew we were the lucky ones. People passing in their hurried, worried cars couldn’t feel Spring. They couldn’t smell it. They couldn’t feel the sun and the way it touched our shoulders. They were locked inside metal and glass, fenced off, corralled like cattle and speeding down a chute into the feed lots of the big cities: Ft. Collins. Boulder. Denver.

C. J., an optimistic, brimming-with-energy, elf-like blonde with a turned up nose and an irreverent mouth, was set to pedal into herself or out of herself, whichever came first. She came across as confident, self-assured, and even cocky, but was a combination of bold, brassy, and exceptionally fragile. When people asked how tall she was, she’d tell them, “Five foot two. And people didn’t think they piled crap that high.” She was more like a young girl than a woman, as if something had arrested her in her youth and held her hostage. Her voice hadn’t matured with the rest of her, and sometimes she sounded like a promoter for the “Hey Kids, There’s a Magic Ring in Your Cereal” Show. She often got carded in bars.

She didn’t like to talk about her feelings, except for short blasts out of the blue. “I’m a friggin’ train wreck,” she said one day when we’d been buying our tent, then let the words sail away with no further comment. I knew she was reeling from her own separation, from the hurt of her husband losing interest and moving across space away from her into new territory and maybe even another woman. I didn’t know much more, except that the “train wreck” analogy resonated with me.

I’d been separated from David for two and a half years, waiting for tax implications to settle before making the final step to divorce. After being Ms. Lonely Heart Supreme, I’d gotten involved with someone I thought was a primal, real man: someone who seemed straight arrow and uncomplicated; someone who was like the hunter stepping into the light from the leaves of the woods; someone who was basically uneducated—the perfect antidote to my cerebral husband of 32 years and his complicated psychological explanations for his behavior. Problem was, I found out too late that this very appealing, big-grinning, primal man was addicted to crack cocaine and pot and tobacco and alcohol, you name it. His main goal in life was to make enough money to support his daughter, who lived with his ex-wife, and to drive a Pontiac Trans Am. Red.

Maybe because I needed someone to fill the void or maybe because I’d been well-schooled in the Christian way, that all people are equal in God’s eyes, I’d taken him in the summer before. He’d needed help with his eight-year daughter who was visiting him for a summer. After a night of smoking crack in the living room of his apartment while his daughter cowered in a corner of his bedroom, he couldn’t bear hurting her any longer. He came to my house the next night, broke down, cried, and asked for help. Not clear about my motives, I invited him and his daughter to move in. After all, he was a lost soul, and at his best, a decent human being.

Who knows why for sure, but I became obsessed with helping the man I’ll call Spinner, even though he repeatedly disappeared into thin air with my VCR and acoustic guitar which he pawned for crack money. This became like a game of “I’m sorry. I couldn’t help myself. I’ll pay you back.” On again, off again, kicking him out, taking him back, I thought I could be the one to help him find his way, to accept responsibility and his own individual strength. There’s a slight chance I had an Atlantic sized heart, but more likely I was a marginalized, lonely woman who needed someone to look after and be intimate with. After all, I’d been with three sons and a husband for a long, long time.

As C. J. and I headed toward Briggsdale, the destination for the day, with nothing else to do but turn the pedals and occasionally shout some smart remark to each other, I kept wondering about the Phyllis I’d once been. The one who was alive, spiritual, curious, and enthusiastic about life. The one who’d once been able to accomplish the moving of mountains, who’d raised three sons, who’d chaired endless committees, who’d been a dedicated Mormon, who’d raised thousands of dollars for good causes, who’d helped launch the Writers at Work conference, who’d edited the Junior League Heritage Cookbook, who’d played piano con certs and accompanied hundreds of musicians, who’d written and published books. She’d disappeared. She’d given up somewhere along the way.

I touched the back of my hand to verify I was still in my body, but how was it possible for C. J. and me to transcend ourselves? To find answers? To move out of our perceptions about how life had to be to be a good?

Our wheels turned round and around, passing discarded cigarette packs, two golf balls, a car light reflector cover, even two strawberries on the shoulder of the road—bits and pieces of passing lives. There were farms and there were sheep who bolted when we rode by. A Peregrine hawk, cows and more cows, and a dead owl whose wings I stopped to spread and whose feathers I decided not to pluck.

After stopping for French dip sandwiches and a pee break in Ault, we hit a hill that required me to try the front derailleur for the first time (I’d never needed to use it on the gentle slopes in Denver). To my dismay, I found I couldn’t shift into the highest gear. Against the recommendation of the bicycle shop in Denver, but in an attempt to have state-of-the art everything on my bike, I’d upgraded the derailleurs at the last minute. At this point in time, it seemed terribly stupid to have been seduced by the phrase “state-of-the-art.”

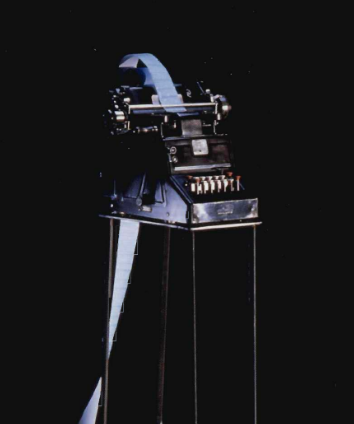

Being more familiar with bicycles, C. J. volunteered to fix the problem at the side of the road while I read instructions out loud from the bike repair manual. After I read from page 26 and after C. J. adjusted the designated screws, I tried out the bike. It did shift more easily but sounded like a sewing machine.

“We’ll see if we can find someone in the next town to refine my repairs,” C.J. said.

After a first day of 47.3 miles, we finally limped into the tiny burg of Briggsdale. Sam and Charity, two kids on swings at the playground, told us how to find Lou, the town mechanic.

“The problem’s in the gear shifter,” he said, stroking his cheek. “But this thing’s too complicated for me. All these gears. You’d better take it to the bike shop in Sterling in the morning. Where you planning to spend the night?”

“We thought we’d camp out in one of the fields,” C.J. said. “Pitch our tent.”

“Not a good idea tonight. The fields were sprayed today. Why don’t you try the local motel? My wife’s mother owns it. She’ll give you a deal.”

We didn’t want to look a gift horse in the mouth, but the room in the Briggsdale Motel was dingy—two beds with limp red poppy bed spreads, an ancient black and white TV with a small screen, a leaky faucet and bulb-burned lampshades. We couldn’t complain for $20 and didn’t. Because the grocery store was closed, Lou’s mother-in-law and her miniature poodle named Bear brought us dinner on a tray. I recorded all the day’s details, including the Wonder bread, tomato slices, carrot sticks, hamburger patties, baked potatoes, and applesauce served on blue Melmac, in my newly-purchased journal. The adventure had begun.

Back on the highway the next morning, we hitched into Sterling in a Mack truck driven by Pat, a combination Navajo-Sioux-Mexican with a sharp-shooter moustache and a great laugh. After regaling us with tales of the truck driver, he dropped us at Jimmy G’s Bike Shop in a square, white-washed, no account building. Jimmy G himself put my bike back in business with a flourish and at no charge. . . .

From Inside my Head.

Over the years, I haven’t known whether to label myself as creative with a vivid imagination, bright but flawed, normal with a certain spin, gifted with a string attached, bi-polar or uni-polar, an aesthetically sensitive woman, someone who’s unafraid to talk about life from the down side or maybe someone who’s touched by madness. Maybe what I am is mad, plain and simple, though there’s no such thing as simple about madness. But it could be that madness is Divine Madness—a kiss from God, a chance to know the full spectrum of humanity, a chance to feel the condition of being tied to the moon and the tides and the pull of the ocean waves, back and forth, in and out.

It takes strength to love so deeply and to sorrow so sadly. There are days when I think I can’t take it any longer—being caught in a riptide, caught between rocks and seaweed and the chaotic tumbling of water. Except for sometimes, there’s a lull and I float out to sea. Or I get washed up on shore to be warmed by the sun until the waves grab me again.

Maybe my tribe and I have been asked by The Someone who assigns tasks for this earthly experience if we would be those to take on the depths and heights of human feeling: the musicians, the painters, the sculptors, the writers. Everyone is assigned some challenge it seems: the delirious, the clogged, the malignant, the bent who can’t straighten, the straight who can’t bend. . . .

My mind feels mad as I try to put this into words or concepts, as I try to capture what it is to be highly sensitive to every movement in a room, to the colors that swim past my eyes, to every nuance of feeling in a friend’s or lover’s face. What it’s like to be so full of feeling with no place for it to go. How it feels to be a body of water, not solid flesh, as though I’m a wetlands with the sadness always spongy beneath the surface. Step wrongly and the water squishes up out of the earth and soaks your and my shoes.

I want to arrange my thoughts about this. I want to come to some definitive conclusion about whether I am well or sick or whether I am a gift or a hex or a bad seed. It seems a curse to have a mind which can behold so much, hold so much, feel so much, and to have it turn against itself and devour itself, tortured with the task of figuring everything out.

Be still, mind. Be still and feel the rhythm of the waves, the lap of water at a lake’s shore, the birds in the trees, the rustle of leaves. Be still and sit in a chair with your legs and hands uncrossed and behold the beauty. Behold another’s face. Hold a sleeping baby. Hold yourself. Be still. Listen when the blues come knocking, and be still.

[1] David and Phyllis Barber, married for 33 years and divorced for six, are devoted friends. This is not a “kiss and tell” or “here comes the judge” account, but rather a recognition that there are many whose idealism gets caught beneath the intersecting wheels of Mormonism and of contemporary life. It is also a willingness to share this struggle to pull free again with others who may have been in a similar place.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue