Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 3

Book of Mormon Poetry James Goldberg, A Book of Lamentations

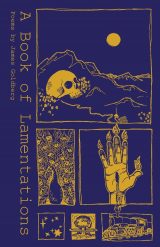

A few years ago I was researching poems written about the Book of Mormon. I had read Eliza R. Snow’s “The Lamanite” (adapted from a poem she wrote before becoming a Latter-day Saint titled “The Red Man of the West”), so I suspected that there were probably a few dozen other poems that either touched on Book of Mormon themes or retold Book of Mormon stories. In the end, I found several hundred of them.[1] It is with some confidence, then, that I can say that the handful of Book of Mormon–themed poems in James Goldberg’s remarkable new collection, A Book of Lamentations (2020), are both unique and necessary contributions to the Latter-day Saint literary canon. Most Book of Mormon poems are either epic celebrations of Lehi’s triumphant journey to the New World or elegies focused on the heartbreaking image of Moroni burying the record of a fallen people. Goldberg’s poems work within this tradition, but they redirect the heroic energy of the epic and the easy sentiment of the elegy into territory that demands us to take seriously the Book of Mormon’s warning that our world, like those of the Nephites and Jaredites, is one of conflict, greed, and self-destructive violence.

In the first poem of the collection, “The Book of Mormon Was Written for Our Day” (3), Goldberg contrasts the platitude that this sacred text was “written for our day” by “a voice from the dust” with topics that aren’t often discussed in seminary and Sunday School: climate change, nuclear proliferation, and violence against the world’s most vulnerable populations.[2]

A voice from the dust

for a nuclear age

for a world leaning in

to its climate’s change

for men gone mad with

homicidal rage which

cannot be quenched

with children’s blood

The contrast between familiar Latter-day Saint talking points and the horrors of the contemporary world is precisely Goldberg’s point, both here and throughout A Book of Lamentations. “You think you know what the Book of Mormon is about,” he seems to say. “You think it’s a book about avoiding the ‘pride cycle’ so that you can ‘prosper in the land.’” But Goldberg reminds us that the generational sins that contribute to climate change and that increase nuclear stockpiles cannot be bracketed off from individual righteousness. Regardless of how many commandments I keep, I can’t prosper in the land if the land I live on has been rendered uninhabitable by ambient radiation or rising global temperatures.

Goldberg finds the representative figure for generational sin in the Jaredite refugee-king Coriantumr. Unlike Moroni, whose tragically beautiful story is a perfect fit for the conventions of the elegy, Coriantumr is a tattered refugee of a war of his own making; Coriantumr is an object of pity, not a subject for elegiac beauty, whose wretchedness tarnishes the gold plates themselves:

For us, a lonely

prophet carved

Coriantumr’s fate

into plates

of tarnished

gold

In a note at the end of A Book of Lamentations, Goldberg glosses “The Book of Mormon Was Written for Our Day” with an insight from Kylie Turley to emphasize that Coriantumr’s tragedy is not merely a consequence of individual choices but of collective values: “Kylie Turley has said that belief in the Book of Mormon is inextricable from the weight of its warning. When Latter-day Saints say we know the Book of Mormon is true, we are saying something about human nature. We are affirming that we understand a civilization that chooses hatred and division is fully capable of destroying itself” (114). This is the warning that Coriantumr brought with him to the people of Zarahemla, and it is the same warning he offers to us today. Goldberg calls this “the truth / he buried beneath / us” (3). Coriantumr’s buried truth, however, is different from the truth that Moroni placed in the ground with the invitation to “ask God . . . with a sincere heart, with real intent” if the Book of Mormon is true or not (Moroni 10:5). Instead, Coriantumr’s is the truth that human beings are

so very capable

of choosing death

and choosing it

and choosing it

and choosing it

until we grow numb

This repetition (“and choosing it / and choosing it / and choosing it”) updates a century-old warning from T. S. Eliot (“this is the way the world ends / this is the way the world ends / this is the way the world ends,” from “The Hollow Men”). It also reminds us that the Book of Mormon is about three American civilizations, two of which (the Jaredites and Nephites) already chose death while the third is increasingly moving toward what Goldberg calls “the consuming / violence of a / total / self-destruction.”

All of the poetry in A Book of Lamentations, whether focused explicitly on Book of Mormon themes or not, returns to this somber note. Goldberg wrote these poems leading up to and including the annus horribilis of 2020, when the apocalyptic messages of every sacred text (not just the Book of Mormon) seemed to take shape in the COVID-19 pandemic, the wildfires raging in Australia and the American West, the perpetuation of state-sanctioned violence against people of color, the Black Lives Matter protests, the (first) impeachment of Donald Trump, and the attendant conspiracy theories surrounding all of these events and more. One poem that feels particularly at home in 2020 is “The Waters of Mormon” (7), where Goldberg writes in the voice of a refugee from the land of Lehi-Nephi fleeing the burden of generational sin brought on by the selfish and narcissistic King Noah, a bloated egotist who had managed to corrupt religious authorities and common citizens alike (see Mosiah 29:31).[3]

I was baptized in the waters of Mormon

I signed up to flee the king

The king, the king

the city of the king

and the ways of the king

even the dreams of the kingI came to the forest by the waters of Mormon

Staked my life to flee the king

The king, the king

the court of the king

and the knowledge of the king

—the searches of the king

Goldberg’s religious refugee is traumatized by the outsized presence of a wicked king who permeates every thought and dominates every line of poetry, eclipsing the possibility for a rhyme scheme of any kind and shutting down any meter other than his own relentless iambs. Reading this poem in 2020, it’s impossible not to see the Trump presidency in the kingship of Noah, as other commentators familiar with the Book of Mormon already have.[4] It’s a terrible irony that, a month after Goldberg published A Book of Lamentations, Senator Mike Lee (R–UT) publicly compared Trump not to King Noah but to Captain Moroni.[5] Lee’s spectacular misreading of the story of Captain Moroni—an anti-fascist who put down efforts to impose a king against the will of the people (see Alma 51)—should come as no surprise, given that Trump is, following Goldberg’s description of King Noah, “the king / who twisted / everything.”

But “The Waters of Mormon” is hopeful that “the shadow of the king” will not shut out all light. The poem paraphrases and then rewrites the very passage from Isaiah that the priests of Noah had distorted in their defense of an indefensible king. Noah’s priests had perverted the words of Isaiah 52:7 (“How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings”) to mean that anyone who spoke ill of the king was denying scripture and promoting fake news:

And how beautiful the hope

of other worlds other waters

other priestsI keep running to the wilderness

keep clinging to the memory of waters

to flee, to flee

the shadow of the king

who twisted

everything.

Goldberg’s poem reclaims the distorted words of Isaiah and in their place finds a space of possibility (“other worlds”) in uncorrupted nature (“other waters”) with uncorrupted ritual (“other priests”). Goldberg himself is one of those “other priests,” offering his Book of Lamentations, like Jeremiah’s before him, both as a witness that Zion has been overrun by Babylon and as a prayer to “Turn thou us unto thee, O Lord, and we shall be turned” (Lamentations 5:21).

James Goldberg. A Book of Lamentations. American Fork, Utah: Beant Kaur Books, 2020. 161 pp. Paper: $15.99. ISBN: 979-8667443285.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Edward Whitley, “Book of Mormon Poetry,” in Americanist Approaches to The Book of Mormon, edited by Elizabeth Fenton and Jared Hickman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[2] All subsequent quotations from this poem appear on page 3.

[3] All subsequent quotations from this poem appear on page 7.

[4] Aaron Brickey, “Doesn’t Trump remind Hatch of a wicked Book of Mormon king?,” Salt Lake Tribune, Sept. 5, 2018.

[5] Lee Davidson, “Sen. Mike Lee says Donald Trump is like Book of Mormon hero Captain Moroni,” Salt Lake Tribune, Oct. 29, 2020.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue