Articles/Essays – Volume 09, No. 4

Close to the Bone | Joyce Eliason, Fresh Meat/Warm Weather

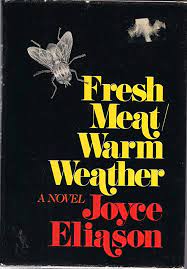

It’s nice to know there was something to talk about in Manti last winter. I’m refer ring to Joyce Eliason’s Fresh Meat/Warm Weather, a confessional autobiography disguised as a first novel, which has a lot to say about growing up absurd in Southern Utah. Published by Harper & Row in the fall, Fresh Meat/Warm Weather has been getting favorable reviews around the country. (It was eighth on the best seller list in Southern California last spring.)

Although Manti is not mentioned by name, the setting is unmistakable, and I can just imagine how the book must be arching some of the local eyebrows. Joyce Eliason lays bare the wound, cutting so close to the bone that I’m sure there are some who can feel the scraping of her knife. (I predict a meeting in hushed tones at the Manti library, perhaps a couple of letters in the city paper—like a garnish on top of two hundred tons of gossip. Note: the four-letter words are enough to keep the book out of town, if anyone wants to press the issue.)

Fresh Meat/Warm Weather is the story of a perplexing Mormon childhood, two failed marriages, a failed career (as an actress), and, in sum, a failed personality. It is also, for better or worse, the Mormon “woman’s movement” novel (“Is it easier to be black and Jewish than a woman and a Mormon?”—Sammy Davis, where are you when we really need you?). The book will undoubtedly provide some solace to those long-ignored “Jill” Mormons whose hearts have been broken by the world but who still have enough good sense to reject the Fascinating Woman solution.

I tried to get recognition through Lee and it never worked out the way I wanted it. I want so much. And through myself this time. . . . Maybe I don’t even want a man anymore. Maybe I just want me.

Maybe. Overall, Fresh Meat/Warm Weather reads less like a novel than a loose collection of reminiscences, recriminations (against self as well as others), and determinations. At its worst, it is open to the charge of woolgathering; at its best it offers us a mini-tour-de-force in the art of recollected anger, in verse as well as prose:

What I want to tell you is

that I hate you

I hate you

I hate you

I hate you

and

I hate me

I hate me

I hate meBut you four times and me three.

The narrative is only roughly sequential; everything is presented in flashbacks. The question is not when something happened, but when the narrator wants to bring it up, so the effect is cumulative—we gradually piece her story together as she ruminates on the pieces. The point of view is first-person-hysterical; the paragraphs tend to be short, without indentation, and separated by double-spaces— sketches. It looks like an exercise in getting one’s dreck together, and I strongly suspect that it was written at the prompting of the author’s analyst (“one sheds one’s sickness in books,” etc.)—see the dedication.

What holds Fresh Meat/Warm Weather together—remarkably, considering the dangers in this self-indulgent kind of fiction—is a letter written by the narrator’s grandfather, which was at his request opened only after his death. (If Ms. Eliason composed this letter herself she is even more of an artist than I think she is; if she stole it, braving her family’s wrath, I salute her pluck and her sense of form.)

We didn’t much get along with Father. But that was hard to say then. I remember of going to the first wife’s house (her name was Mary) for dinner and all the kids and the big table. She always served soup out of a big bowl in the middle. One night the cat got frantic and jumped on the table and right into that big bowl of soup. It didn’t bother Mary at all. She got the cat out of the soup and continued dishing up our portions. My mother never fully recovered.

Grandpa Erastus’ letter, quoted in sections throughout the novel, helps to ballast the narrator’s emotional freight. Grandpa Erastus himself apostatized from Mor monism, struggled against the frontier—and the Ward teachers—all his life (“There was no way of keeping fresh meat in warm weather”) and achieved an integrity of his own—which puts his granddaughter’s trials in perspective. Things were different then, in the same way. Without Grandpa’s letter, Fresh Meat/Warm Weather would be no better than a good cry in the ladies’ room. With it, Joyce Eliason has constructed a small masterpiece out of a small problem.

Fresh Meat/Warm Weather. By Joyce Eliason. Harper & Row, New York, 1974.145 pp. $6.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue