Articles/Essays – Volume 02, No. 1

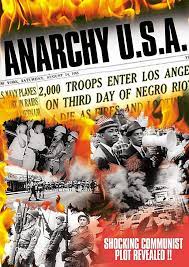

Confusion, U.S.A. | John Birch Society, Anarchy, U.S.A

The John Birch Society is showing a film around called “Anarchy, U.S.A.” I saw it at a meeting of Young Republicans at the College of San Mateo on January 10, 1967.

The point of the film is that there is a substantial connection between Communism and Civil Rights demonstrations. Although Communists may indeed have taken part in such demonstrations, I could find no evidence of it in the film. Nor could I find any information in the film to support its assertion that the Algerian Ben Bella was a Communist. The film said that Castro had once told people that he (Castro) was not a Communist, but that later he told them he was one. Then Ben Bella is shown saying that he is not a Communist (leaving the viewer to infer that he must be one too). Finally, Martin Luther King is shown shaking hands with Ben Bella, and is quoted as saying that he (King) isn’t a Communist either. Rich ard Nixon is shown with Castro, but there seems to be no indication that Nixon is a Communist, because he never says that he is not.

One picture shows men marching along abreast with Castro, locking arms. The next sequence shows Civil Rights demonstrators marching abreast, with arms locked. I suppose the idea here is that people who lock arms are Communists. The film exposes the viewer to riots in various places in the world, some of which were undoubtedly connected with the activities of Communists; but I could find no rational connection between such riots and Civil Rights demonstrations.

Whoever made the film was probably unaware that the “black belt” in the South is not a phrase of recent origin, but refers to the cotton belt. The “region derives its name from the black soil which is prevalent [there] in contrast to the red clays to the north and south” (Cochran, et al., Concise Dictionary of American History, p. 99). The film implies that “black belt” is a name for a new country of Negro Communists — the “black” referring to skin pigmentation. A similar distortion occurs when the film implies that a Castro slogan “Venceremos!” (which probably means “Let’s Win”) was translated into English by Negro Communists and set to music as “We Shall Overcome.” Actually the music is an old Baptist hymn called “I’ll Overcome.”

Two Negroes in the film speak against Civil Rights. They are persons who once embraced Communism, but saw the light and returned to condemn it. One, a little old lady, tells such a pat story that the viewer suspects she might have picked it up at Birch headquarters. The other is a poor fellow with no teeth. He appears so ignorant and imperceptive that one begins to wonder if he was drummed out of the party for giving it a non progressive image and that was when his feelings were hurt. Anyway, the crucial thing about the two renegades is that their testimonies did not make the crucial connection between Civil Rights movements and Communism, except to say that such demonstrations make Communists happy. But then, doesn’t every sort of disturbance in our society make Communists happy, including conservative opposition to the Civil Rights movement?

The film reiterated again and again a five-point Communist “take-over” system. Then it said at one point that the Communists say things over and over until people believe what is repeated. Well, I didn’t believe in the five point system no matter how many times it was flashed on the screen. The film said that Communists identified virtuous causes with “bad smells,” which, in my opinion, was what the film itself did with the Civil Rights movement by identifying it with Communism.

The film spent much time concentrating on mutilated bodies of people killed in Algeria. I suppose the point was to scare viewers into believing that Negro rioters might mutilate their bodies, as part of a world-wide Communist plan to carve up bodies.

The thing that did move me in the film was the depiction of Negroes marching and swinging, singing “We Shall Overcome.” I felt a real kinship with them and their cause, and I empathized with their ministers who cheered them on to strike out for equality. All of this was very inspirational. But I suspect that it was not this message that the editors of the picture wished to put over.

I rather think they wanted the viewer to see something despicable in something beautiful. They wanted to place a Communist context on even the most praiseworthy aspects of the Civil Rights movement.

The film appealed to people with Negrophobia. It gave them an excuse to claim that their discrimination was not racial, but political. Would you want your daughter to marry a Communist?

“Anarchy, U.S.A.” is a film produced and distributed by the John Birch Society.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue