Articles/Essays – Volume 11, No. 4

Editor’s Note

Earlier this year David Whittaker informed Dialogue that his long-awaited bibliography of Leonard Arrington’s works was ready—and that it would coincide with the 20th anniversary of Arrington’s trailblazing Great Basin Kingdom. We agreed that the winter issue would be the right place to hold the celebration.

Soon after that we learned of the deaths of three senior Mormon historians—Gustive O. Larson, David E. Miller and T. Edgar Lyon. Their influence upon Arrington and a whole generation of other historians cannot be denied. Dr. Larson, 81, was professor of history at Brigham Young University and the author of three important books: Prelude to the Kingdom, The Americanization of Utah and Outline History of the Mormons. Dr. Miller, 69, a University of Utah professor, was known for Hole in the Rock: An Epic in the Colonization of the Great American West. He was co-editor of Utah’s History.

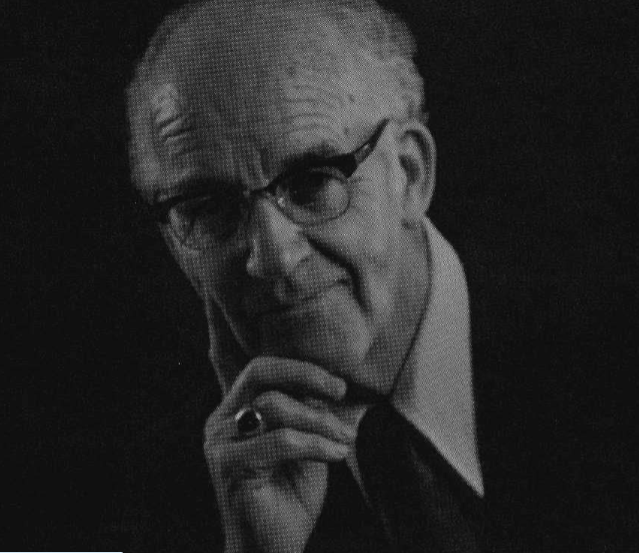

Because of T. Edgar Lyon’s influence on the founding editors and on the present editors of Dialogue, we have chosen to use his picture on the cover and to publish one of his best-loved lectures. We have also included Lowell L. Bennion’s funeral tribute and a brief biography from Davis Bitton. Doctor Bennion, founder and long-time co-director of the University of Utah institute program, was Dr. Lyon’s close friend and associate for more than forty years. Dr. Bitton, a fellow historian, has worked with Dr. Lyon on the Nauvoo restoration.

“Brother Lyon” as he was called by a legion of affectionate students at the “toot” was the first teacher to make church history come alive for me. Although I had studied it in church and seminary, it was Brother Lyon’s twinkling-eyed lectures that changed the people of Mormondom from larger-than-life cardboard dolls to truly inspiring human beings, models with lessons to teach. My interest in those people and their times has never failed, just as Brother Lyon’s energy never failed. We students used to speculate about the source of that energy. It was not what has been called “nervous energy.” It came instead from some deep wellspring of vitality with an intelligence and a steady, calming cheer carried forth on a voice always on the verge of laughter. One of our number finally decided that he owed this energy to his cat naps—we had all caught him at them—sitting straight up at his desk during the ten-minute intervals between classes. (He always carried himself like a soldier—no one ever saw him slouch.) It was rumored too that he was able to catnap right in class, during his own lectures, with his eyes wide open!

I am grateful that I knew him then and grateful that I was with him at the Boston Education Week Series the year before his death. I heard him give his “Old Nauvooers” speech and was able to spend several private hours reminiscing with him. He had spent the previous months nursing his wife back from cancer, and though he attributed her healing to the powers of the priesthood, I knew that at least part of that power came from his own nurturing personality. For I had grown up in the neighborhood where he and his family lived, and I knew first hand of his devotion.

I taped his Boston speech, and I have played it several times since his death. The miracle of media reminds me of the miracle we, his friends and students, look forward to. I speak of that day when millions shall know Brother Lyon again.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue