Articles/Essays – Volume 31, No. 2

Ehab’s Wife

For me, Jesus’ home is my husband’s, and it is also the birthplace of my extra-American consciousness. I was never allowed to see it as a tourist. I never listened to a tour guide’s simplistic explanations of “The Holy Land.” I was a hometown boy’s American wife. Something of an Eliza Doolittle, I didn’t belong with either “his kind” or “my own kind.” Also like her, I have never been able to see “my own kind” in the same way again. On our first trip we were married in the little Greek Orthodox church called The Annunciation that is so popular with bus loads of visitors. On my wedding day I felt incongruous as I was the object of curious looks from travelers.

It was in my husband’s interest not to fulfill my naive expectations about Israel. He gave me the alternative tour. Standing behind the noisy bus depot in Jerusalem, I tried to see the shape of a skull in a hillside, but the pilgrimage mood had never been set. Naturally, I found the typical Christian tourist highlights all very speculative. One of our stops was Akko—not the Dead Sea or Masada, not a site renown among Mormon Sunday school teachers or Hollywood executives. Akko was first a crusader fort, then an Arab Islamic stronghold against Napoleon. Unlike the wailing wall, this proud moment in Arab history was not overrun with sun-screened Americans. Until my first trip to Israel, I had never noticed the American flag flying outside our LDS church at home. Now it irritates me: this inappropriate and thoughtless show of nationalism where national boundaries should dissolve in universal Christian love.

These trips to Nazareth were my first profound experience of feeling my Americanism separate from myself. When I saw a small Palestinian flag in my sister-in-law’s room, I had to think slowly and carefully to con struct her point of view. Not that our summers in Israel have been overtly political experiences; mostly they’re two unglamorous months of extreme heat and limitations to which I am not accustomed. My awakening has not been a matter of dramatic political confrontations, but of living a different life. As a mother, I’m used to being in charge of my life and having easy options like movies, ballet lessons, and Popsicles at my fingertips. In preparation for the long somewhat trapped afternoons I anticipate in Nazareth, I jam our suitcases with every conceivable child’s entertainment: Play Dough, paints, cassettes, even an inflatable pool. I attempt to recreate our American life, and am happy when I fail. The duality of our life there is striking; it’s both wonderful to be there and so hard. My feelings never settle into either frustration or enjoyment, but hover between. Every morning this summer my three-year-old daughter woke up and asked, “When are we going back to El Paso?” As Disney’s Hebrew version of The Little Mermaid played, she listened perplexed then offered, “It’s broken.” More than just her language, she misses what’s familiar like bathtubs. She misses ease. I miss having a car; being free to move about. Freedom. A word that accompanies any flourish of American patriotism, but for my daughter and me in Nazareth it comes down to pan cakes, chocolate chip cookies, and movies that are easy to get and easy to watch. When it’s most challenging, I cling to the promise of going home, but home has never been the same.

It is especially hard for a three-year-old to be a displaced English speaker. Of course it’s not merely Arabic words she’s exposed to while we’re there, but Arab ideas. Modesty, individuality—these ideas are more a matter of living than of translation. I learned to feel the same shame for wearing a bold University of Utah sweatshirt as I did for thoughtlessly dressing near a window: wearing my mod Americanism loudly instead of keeping it covered. In my husband’s world, our interests, the details about our lives, belong to our families and are for their eyes only. As for personal territory, my husband and I can’t have an argument by our selves, everyone wants to get involved. And why not? The unit, not the individual, is the basis of that life. Ownership, self, identity—my understanding of these ideas was decidedly American. Not just words in need of translation, but a question of where boundaries lay. I can’t switch from American to Arab like changing languages. My Americanism doesn’t dis solve like Tang in water. No matter how accustomed my mother-in-law’s neighbors become to seeing me, I’m still foreign. This has added to the typical insecurity about being accepted by one’s in-laws. Once belly-ach ing to my husband, I complained, “Your family doesn’t ask me about me. They don’t ask me about my life. They don’t seem interested in our other life. My family is so interested in you. They have so many questions about what it’s like to be a Palestinian.” And before he thinks his re sponse through, he says, “Well, they already know about America.” Hmm. The more I’m there, the more I do feel like a stereotypical Ameri can, but is it possible that the sum of their political and social notions about America is all that I am?

I had noticed that very often “American” means arrogant, young, self-righteous, and foolish. “American woman” generally means promiscuous. American marriages are notoriously temporary. The Arab-Israeli divorce rate is almost non-existent compared to ours. Once, when I was walking alone to my father-in-law’s, a young local took me for a tourist. He looked at me too long, too closely, and too sexually. All he said was “How are you,” but his implication was obscene. I was furious. In the States my Arab husband has suffered many similar stupidities. A real estate agent, while showing us around El Paso, upon realizing my husband was not a Jewish-Israeli but an Arab-Israeli, pointed to the impoverished landscape of Juarez visible from I-10 and said, “That must remind you of home.” During my engagement I was encouraged by concerned family members and travel agents to read Not Without My Daughter, a book which apparently authorized their view that all Arab men are Moslem, sexist, and sinisterly underhanded. During the summer of 1995 I had ca joled my husband into attending our graduation ceremony and being hooded together as Ph.D.s. We learned, too late, that the center piece of the commencement would be the presentation of an honorary doctorate to Teddy Kollek, former mayor of Jerusalem. Mormons tend to be captivated by Israel and, because of narrow interpretations of certain prophecies, are fixated on the Jewish people. A stadium of unknowing, unthinking Mormons was aflutter at having this figure in their midst. My husband, on the other hand, was confronted with a man who had taken land from Palestinians and supported the unfair construction of Jewish settlements in Jerusalem. We watched the presentation from the front row—the only two people still seated as the crowd was swept into a eu phoric standing ovation—I wished our seats hadn’t been so good. It was a most powerful and personal illustration of the experience of being a minority.

My own ignorance and prejudices continue to be exposed. I still ask the same questions: “Now, explain to me again how Jewish is a religious distinction not a racial one?” I continue to struggle in Nazareth with the litter and the stench of the market. It contrasts with my minty-fresh American life. Woodsy Owl’s “Give a hoot, don’t pollute” is an indelible fixture in my memory of youth. Sanitation, it had seemed, was a question of character. I hadn’t known until Nazareth that sidewalks, swimming pools, public libraries, and quaint well-kept parks are a matter of political resources and influence. We flooded to our parks when I was a child with our quilts and snow cones after the Fourth of July parade. “Why don’t you want to go?” I asked my husband each Fourth of July after we were married. I really didn’t understand until I went alone to a celebration and for the first time saw the self-righteous show of arms—the self-deception that had always escaped me before. An American girl who’s had all she’s needed needs a reminder that everyone’s paradise isn’t covered with freshly mowed lawn and neatly attended waste receptacles. In El Paso, where my Voice and Articulation students are 70 percent Hispanic, when in need of a quick memorized text to use in our work, couldn’t we use the Pledge of Allegiance? American. Allegiance. In a classroom in El Paso or on the streets of Nazareth, I see that in some eyes I am guilty of my Americanism—my wealth and naivete—my need for sunglasses and my Patagonia child-pack. And though I’d like to, I can’t belong with other young Arab mothers hoisting children onto a bus in the heat. How can I share their indignation or even fear of uzi-armed Jewish-Israeli soldiers seated across the aisle when my tax dollars paid for their guns?

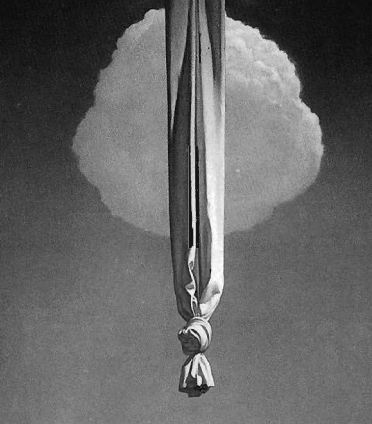

On my first trip I noticed people called me “Marte-Ehab,” which means “Ehab’s wife,” instead of by my name. Four trips ago my Ameri can feminism bristled at that custom, but after six years of living along side this man my reasons for enjoying being identified with him have deepened beyond mere political ideology. At the airport Marte Ehab Abunuwara is an Arab, with all that that implies to a security employee at Ben Gurion. Innocuous American tourists pass through the gates while we are detained and searched. This infuriating hours’ long ritual helps me forget the heartache of leaving my husband’s family; “Marte-Ami,” my sweet, heart-broken mother-in-law. Repacking my belongings, I can still feel my sister-in-law crying. Five hours after we’ve left Nazareth for Tel Aviv, the sky is just getting light. By the time we board the plane, I’ve replenished my supply of amusements for the kids. The air-conditioned cabin, the soft drinks—English is being spoken around me and it’s almost already American soil. I feel torn in two. My world view has been tossed into the air just as I was. An Arab bride, I was hoisted in a chair above the heads of dancing, inebriated Arab men. My polite smile did a poor job of hiding my distrust and anxiety, but I’m no longer holding on to my American vantage point as I once was. I’ve occupied another place in the world. If I had that moment again on the Nazareth street when the rude young man insulted me with his stare, I wouldn’t call him some belittling name. I’d only want to change my placement in his eyes—change my pinkness, my hair, my language, my name, my foreign status by saying, “Ana Marte Ehab Abunuwara”: “I am Ehab Abunuwara’s wife.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue