Articles/Essays – Volume 32, No. 1

Ella Smyth Peacock: Seeking Her Place in the West

Like the early Mormons whose beliefs she would eventually adopt, landscape artist Ella Smyth Peacock early on sought refuge in the west.[1] She was born in 1905 in Germantown, near Philadelphia, a city created in 1681 by god-fearing visionary William Penn as part of a “holy experiment” to provide a sanctuary for the religiously persecuted. As Joseph Smith would nearly 200 years later, William Penn—a multi-talented man with radical ideas and a determined spirit—designed a city with streets laid out in a grid, in precise symmetrical right angles. However, unlike the Salt Lake valley, this eastern land, which originally was inhabited by the Algonquin Indians, lay between a bay and a fresh water lake. It was rich with river valleys, gentle mountain slopes, and dense forests.

Despite the land’s natural amenities, Ella long wanted to leave the east coast. She didn’t care for the fertile, intensely green land and didn’t value the refined lifestyle her 17th-century American ancestors had bequeathed her. She disliked the dance cotillions and afternoon teas that asked for so much in propriety and appearances, and she eschewed the proper and “self important” Philadelphia society. At a young age she felt anxious in groups outside her family and, as she matured, felt out of place, living an unconventional life that had not lead directly to college and a marriage befitting her family. But as Brigham Young had once ad vised the Mormon faithful, Ella’s father coached his young daughter to follow her own light. She envisioned a different, less controlled land, a place she could live free from others’ expectations. Thus inspired to seek her own purpose, she imagined life outside Philadelphia society and eventually—though not for fifty years—escaped the east for that space and autonomy in the western desert.

Young Ella was raised in a religiously conservative atmosphere next door to her maternal grandparents, Mary Emily Munhall and well known evangelist, Leander W. Munhall. She was her parents’ third child; two more would follow, making her the middle child in an accomplished and remarkable family. And she had some of the traits middle children often bear: a tendency toward insecurity, a feeling of being overshadowed by the competence of the older children and the charm of the younger.

Perhaps because of these personal uncertainties, all her life Peacock admired strong and independent-minded men and women, eventually modeling her life after their qualities of self-reliance and unconventionality. Most memorable were her grandfather and her father, both strong men with sensitive spirits and clear convictions.

When she was in her ninetieth year, Peacock remembered Grandfather Leander W. Munhall as “quite a lively person who had entered the Civil War as a drummer boy, survived thirty-three battles and mustered out as a lieutenant.” She admired his innovative lifestyle, carried out at the same time the LDS church sent missionaries around the world. Grandfather Munhall—a Methodist evangelist who traveled widely, knew the Bible “from front to back,” and wrote extensively about his conservative, religious opinions—went on his final mission to California to preach with Aimee Semple McPherson. It was 1933, and he was ninety-one. As a child Ella loved sitting with her brother and sisters at her grandfather’s knee, listening to lively stories of the Civil War and his proselytizing experiences; he was an outspoken man, convinced that so ciety and especially Methodist doctrine were becoming too liberal.

Weighed down by the complexities of society, Ella’s father George Albert Smyth impressed Ella deeply with his understanding and encouragement. He was a man with artistic sensitivity who had capitulated to his parents’ demands that he become an attorney. Knowing he couldn’t bear a lifetime of criminal law, he became a corporate lawyer, working part of the time for Young Smyth Field Company, his family’s Philadelphia wholesale import/export firm, and escaping to the research library as often as possible. In her father Ella found a soul mate, another who objected though he sometimes succumbed to the pressures and expectations of others. But after he’d had his second nervous breakdown, Ella’s mother, who was also challenged with a new baby, sent the “nervous” Ella to her maiden aunt Dibbie for calming. Here the six-year-old Ella learned to make pincushions by stitching together small circles of felt and cardboard; she gave one to her father, who kept her gift in the breast pocket of his suit coat.

Though he died tragically when she was just thirteen, Ella’s father marked her profoundly with his belief in self-direction and his passion for honest work. Most critical to Ella, however, was the license her father gave her to value herself and to do what she felt she had to do, advice liberating to a young woman who “back in Philadelphia was supposed to do just what she was told.” He told her to “choose just what you want to do in life and go after it.” She took his counsel to heart, but, as it turned out, could not do wholly what she wanted for five decades. When her father died, Ella was enrolled in the private Quaker schools she had at tended from the beginning, strict, refined, and academically sound institutions that gave her a classical education. Yet within two years, the family business collapsed and Ella’s mother, Adelaide Munhall Smyth, was left bereft of her comfortable life. Ella was then forced to attend a public high school, a place she “couldn’t stand” because the students shocked her with their disrespect and frivolity. So she quit in December of her senior year, simply refusing to abide the personal discomfort it caused her. Thus, at the brink of her adulthood in 1923, she established what would become lifelong habits of willfulness and self-direction.

Obliged to survive with a very limited income, Adelaide Smyth modeled for her daughter the take-charge courage of truly independent women. She sold the family’s summer home on the New Jersey shore, the site of Ella’s fondest childhood memories, and turned the family home in Germantown into rental apartments. And she raised her younger children alone for the next sixteen years.

Ella Smyth’s subsequent decision to attend art school seems founded more on default than on response to a calling because she had had no art instruction or experience. Instead, her mother had encouraged her to study music. She remembers, “I loved music and loved playing the piano, but that wasn’t on my mind. I tried studying music at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, but decided I didn’t want to do that. I got to talking with another girl who was going to art school, and that just sounded to me like what I wanted to do. I just hoped I could do it.” “Gillmer,” as she was then called, studied art for one year at the Maryland Institute in Baltimore, financed by a “private scholarship” from her mother’s good friend. The next year she enrolled in the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, a small private school that had been founded in the 1840’s as an “experiment in training for the useful and beautiful.” Her work here reinforced the work ethic that had been modeled for her in her childhood home and established in her own mind an image of herself as a quiet rebel against many of the restrictions common to her culture.

She attended three years on a school scholarship, working during the school year and summer breaks to pay for her supplies. Gillmer’s education at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women established her opinions about art education: Here she learned from practicing artists, not from instruction in theory and technique, but from weekly critiques and hours of individual, independent work. She learned, too, of her love for painting outdoors, frequently leaving during class time—against the rules—to paint outside. She graduated in 1927 with a degree in Illustration and quickly secured her first postgraduate job working for a sculp tress—posing nude in an outdoor garden beside a live deer.

The Depression made her stronger and formed a conviction she would hold long into her old age that taking government handouts was wrong. Gillmer Smyth supported herself and later her family at a variety of jobs, including painting, for the next seventy years. She spent the De pression years expanding her art experience: painting portraits on commission, sketching at the Philadelphia wharf, taking a few courses at a teachers’ training college, and—importantly—driving out west pulling a trailer, sometimes collecting antiques along the way. But she also worked hard to persevere through the rough times of the thirties, continually employed at a colorful variety of jobs, all design related: She carved frames and applied gold leaf to them, created decorative wooden brooches she sold to Saks Fifth Avenue, updated antique jewelry for a Philadelphia jeweler (a painful task for her aesthetic), painted designs on lampshades, and, finally, ran a business with a former art school friend—remodeling and decorating basement recreation rooms for wealthy families in Germantown. The carpentry she spent so much time doing toughened her hands, eventually making them too stiff to play the piano and contributing to her arthritis.

Recalling only one childhood “crush” on a boy, Gillmer claims she never dated in high school or art school. Perhaps the challenge of virtu ally supporting herself for the fifteen years after her family’s financial ruin had toughened Ella’s resolve to remain autonomous; perhaps her constant self-effacement and insecurity about her appearance (“I’ve always had too much nose,” she told me) preempted the usual expectations about marriage held dear by most young Philadelphia women in the thirties. At any rate, Ella Gillmer Smyth Peacock remained clearly ahead of her times as an independent woman. In fact, she did a man’s work and broke male barriers throughout her life, experiences that developed qualities that would later help her survive and would influence the quality and production of her best work.

Gillmer Smyth was a 34-year-old woman who “wasn’t looking for a husband” and who claimed she “wasn’t ever going to get married” when she met an Englishman named William Francis Bailey Peacock “over a hammer and saw.” Against her mother’s warning that Bill Peacock was “beneath” her socially, Gillmer married Bill in 1939. She was thirty-four years old and he was almost forty. Bill, whom Peacock remembers as “calm and good for me,” had left school at age fifteen to join the British army at the start of World War I in 1914. The carpentry skills he’d learned since the war and those Ella was developing gave the newlyweds their start. They lived in one of the apartments her mother had made in the family home, remodeled more space into apartments, and eventually bought the apartment house from Ella’s mother Adelaide, who by then was in her sixties. Two years later in 1941, Ella answered the country’s call for women to support the war effort and enrolled in a vocational high school to learn drafting. She learned quickly and worked as a draftsman for most of the next thirty years, earning the main part of her family’s income.

In 1949, when their only child Bailey was five years old, Ella and Bill moved out of the city for Bill’s health, to Wayne County, Pennsylvania, where they bought a barren dairy farm though they “didn’t know a thing about cows.” The barn was dilapidated, and the cows they bought were diseased. So they bought a new herd and both Ella and Bill worked the farm side by side—milking the cows and running the dairy machinery. Bill enjoyed the farm life and the country air, but Ella remembers, “I always had it in the back of my mind to move out West.” The dairy enterprise wasn’t profitable enough to support their family, so Ella left for six months to work as a draftsman in New York City, commuting home on weekends to see Bill and Bailey. She remembers her work environment:

The fellows were very nice, easy to work with, and there wasn’t any problem though I was the only woman in the room. But one man from Pennsylvania told me a married woman shouldn’t have that job, that it should be a man’s job. He called me “sir” all the time and I called him “mam”! I sat beside him and one time caught him studying my drawing; I was a better draftsman than he was; I knew that. My supervisor said when he wanted a job done right, he’d give it to me.

Though women could easily find work doing a “man’s” job on the east coast in post World War II years, discrimination was clearly an issue. For one year in 1954, Ella taught a correspondence course in drafting, mostly evaluating students’ work on programmed assignments. She signed only her initials to her critiques because the school didn’t want it known that all the instructors were women who had been hired because they would work for less money—$50.00 a week in this case.

The Peacocks found the Mormon church during their days in Wayne County, but their connection to Mormonism had actually begun much earlier. Just before Ella’s father died in 1919, a distant relative, the Mormon apostle and convert Richard R. Lyman,[2] had contacted him, seeking genealogical information. So, on one of Ella’s trips west with her mother during the 1930’s, she and Adelaide drove to Salt Lake City, curious to see the Mormon headquarters and meet their relative. Apostle Lyman took Ella and Adelaide Smyth upstairs to meet apostle George Albert Smith, who was standing at a lectern speaking to the women of the Relief Society. Apostle Lyman “introduced Mother as Mrs. George Albert Smyth. That got a laugh from everyone.”

Thirty years later in 1962 when Bailey was finishing high school, Bill and Ella contacted the Mormon church again, this time to ask about the colleges in Utah—”not wanting to be missionaried,” but curious and thinking it might be nearing time to sell the dairy farm, so Bill could re tire and the family could finally move west. They had recently read an article about the Mormon missionaries and had spoken of their interest to a clerk at a local A&P, who, in turn, had mentioned it to the local missionaries, Salt Lake boys Greg Hawkins and Gary Workman. The young men found the Peacock’s dairy farm on a country lane, quite close to a small Catholic monastery, outside the town of Honesdale. Only Bill was home, but the missionaries remember he was “tickled pink” to meet them and introduced them to the Peacock menagerie that included sheep, chickens, rabbits, ducks, and dogs.

Elders Hawkins and Workman met with the Peacocks weekly for four weeks, teaching them the Mormon gospel. Ella remembers both she and Bill were especially intrigued by the plan of salvation. They changed their habits, according to Peacock’s recollections, in order to join the Mormon church. Ella quit cigarettes “cold,” and Bill gave up the drinking “he’d picked up in the army” and “the tea he was raised on.” After they were baptized on February 25, 1962, Ella says she remembers thinking the Methodist church women’s organization was a “cooking and baking club” and she expected that the LDS Relief Society might be different, “but it’s too much of that too,” she said. “I didn’t go for Relief Society very much; I still don’t, but it isn’t necessary.”

The Peacocks finally sold their dairy farm and moved west in 1964 to Salt Lake City where Ella worked for four years. They lived on “C” Street, finding friendships in the church and worshipping regularly in the Salt Lake Temple. Although she had long desired to move west, Ella ran into some practices in Utah that conflicted with her upbringing and art training. While in Salt Lake, Ella took a figure drawing class because she “wanted to get back into painting and wanted to get some criticisms.” At a time when most schools across the country were using nude models for life classes, this one was still unsure about the practice. She doesn’t re member the school, but she remembers: “They had a nude model, but the trouble was the instructor didn’t know how to run it. You know, the model poses for a certain amount of time and then rests. It’s professional for the model to put on a robe and walk around then. They don’t walk around without any clothes on and talk to people. But this model didn’t know that and the instructor didn’t know that. It wasn’t professional at all.”

Peacock was more disturbed, however, by the sexist hiring practices she encountered in Salt Lake City. All the private engineering firms she applied to refused to consider her for employment. She remembers one in particular: “They wouldn’t look at a woman draftsman and even told me so. I asked, ‘Would you tell me why?’ He said, ‘You have to be extra good if you’re a woman and if you’re that good, the men don’t want you around.'”

Despite her rebuff from private firms, Ella did get hired for part-time civil service work with the Veterans Administration Hospital in 1964 and was quickly promoted after taking the exam for a permanent position, earning two raises and advancements while working there. After living in Salt Lake City for four years, the Peacocks read about the small farming community of Spring City, a National Historical District about 100 miles south of Salt Lake City in Central Utah’s Sanpete County. They drove down one Saturday to see the town and fell in love with the area and a one-hundred-year-old adobe house that was for sale just off Main Street. They bought it, but before moving into their newly purchased house, Ella realized she could reap more retirement benefits if she worked longer, so Bill and Ella drove an airstream trailer to Miami where she continued to work two more years for the V. A. Hospital. When the Peacocks returned to Utah in 1970, they immediately moved to Spring City and lived in their trailer on the property while they fixed up their new home.

In Spring City, Ella seemed to become herself, to settle finally into the westerner she was meant to be. “You can see the sky here, and you can’t see the sky in Salt Lake, you know,” Peacock insisted. And it’s true. Because Sanpete County is at least a thousand feet higher than Salt Lake City and because it escapes the inversion layer that obscures the air in the northern counties, the sky—sharply blue and alive with clouds in the summer and crisp azure between storms in the winter—seems vaster, the horizons lower and wider. Ella remembers, “I just thought I could paint around here for the rest of my life.” And she nearly did. She spent most of the next twenty years out looking—especially when the sky was “doing something”—and documenting vanishing old homesteads and arid desert mountains.

It was here in Spring City that Ella established herself as the “matriarch of Utah artists,” and it was here that most collectors of Peacock’s paintings learned to love her work and admire this woman who is so much like her interpretation of the desert. From 1970 until late 1997, Ella lived at 12 East Third South in her taupe-colored adobe house built in the 1860’s. Large fir trees shade this old pioneer home and the struggling sagebrush Ella and Bill transplanted from the desert. Ella opened her old Mormon pine door to many over the years—local artists and good friends Lee and Joe Bennion, close friend Helen Madsen McKinney, artist and devoted neighbor Osral Allred. Strangers appeared too: collectors hoping to buy her art. Memorial Day visitors touring the historical homes of Spring City, and the curious from out of town wandering over from the Horseshoe Mountain Pottery across the street.

My first tentative knock at Ella’s door in 1984 followed a serendipitous stop at the pottery. When I showed my pleasure at finding such good art in this small out-of-the-way town, Joe Bennion pointed across the street, “Why there are lots of artists in town. Ella Peacock lives over there and next door is Osral Allred,” he began. Just then, eater-cornered from the pottery, on the porch of her adobe house, a tall, thin woman wearing paint-splattered work clothes, her long gray hair wrapped around her head and held back with a black headband, called sharply, “Jeff! Jeffrey! You come back here!” Her Golden Retriever dashed ahead of her from the porch and toward Main Street. A few minutes later I was on her porch at her one hundred-year-old, hand-grained front door, which she opened, allowing me in to a sudden sensual treat: earthy smells of oil paint and turpentine, soft light illuminating dove gray walls carefully painted with a waist-high frieze featuring Native American motifs, parched antlers in a window alcove, birds’ feathers tucked here and there, and, prominently, in the dining room studio, Ella’s old paint splattered wood easel, her brown wool fedora perched on its top. Paintings hung, stood, and leaned everywhere—portraits from her art school days, a “nearly finished” painting of the Manti Temple, the small treasure First Sight of the Desert, and many documents of Sanpete’s gentle landscape. The room was a study of the earth’s sage grays, blued greens, and warm ochers; here was clearly the home of an artist in place and at home with herself.

For eight years, “Rollo,” as her husband called her (perhaps after the English sweet), and Bill established their place in Spring City together, participating with other couples in church and community activities. They also explored the old mining towns and massive fiery rock walls in southern Utah, places where Bill could fish and Ella could paint. They took road trips all over the country: back east to visit all their previous homes in Pennsylvania, throughout the western states and into Mexico. According to Ella’s recollections, Bill, “a strong, manly-looking man,” was “good with people, always talking to somebody” if they went some where he couldn’t fish or hunt. And she remembers hunting with him, satisfied that she’d always failed to kill any animal.

When he died of a brain aneurysm in 1978, Ella lost her soul mate and best friend. He had motivated her “to do things” and—like her father—encouraged her to do just what she wanted. He had done most of their cooking because she didn’t like to, though he eventually taught her to cook pot roast and bake an apple pie. Still, she didn’t cook much after he died, and she never returned to their four poster bed, preferring to sleep instead on the sofa bed in the living room.

At ninety-three Ella still stands nearly all of her five feet, eight inches in height; she has remarkably large blue eyes and waist-long gray hair, always pulled back and knotted into a bun. For the past thirty years, she has worn a headband, not for effect, but just to keep her hair away from her face. In her days in Spring City, Ella usually wore men’s clothes: khaki slacks or jeans, long sleeved shirts, boots, and various caps and hats when she was outside. She was well known in town for her driving and “looking” habits: She would drive throughout the 15 miles of the Sanpete Valley—usually from Indianola on the north to Manti on the south—anytime the “sky was doing something,” accomplishing her “full time job of looking” at the landscape. Whenever she would settle on a spot to paint, she would pull off to the side of the road, sometimes all the way into the drainage ditch to avoid curious motorists. Here she would paint inside her car all year long. Well known in Spring City are her crashes—the times she looked too long at a particular spot and rolled her car or swerved into the ditch. Fortunately, passing motorists always res cued her. Of course, sometimes she was offered rescue when she was intentionally in the ditch, painting some barn or house about to be demolished or just some sagebrush against the mountain.

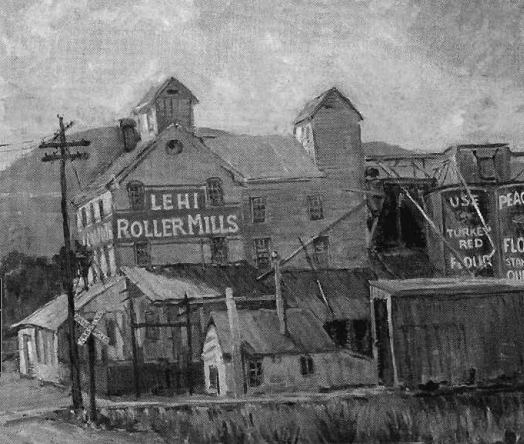

She did most of the work on her paintings outside, first sketching briefly with her brush. A thrifty painter, she applied paint sparingly with broad brush strokes in the grayed colors of the parched desert, sometimes in her last years leaving spaces of bare canvas. She was particular about where she settled down to paint and sometimes, on returning to work again on a painting, grew frustrated if she could not remember where she had been sitting when she began the painting. She said she had found the perfect place to paint the Lehi Roller Mills, one of her fa mous subjects outside Sanpete Valley. She could sit under the freeway overpass and still get a good view without anyone stopping by to watch her. She would usually return to her studio to finish her work and there evaluate her paintings with a critical eye, questioning if this one “worked” or if it was merely a “flopperoo.” In the corner of her kitchen, she would make the frames she had hand carved since her days in art school; simple and with natural lines, they are tinted with the colors from her “slime jar” of palette scrapings.

After Bill died, she still took road trips to scout out places to paint, often with her close friend Helen Madsen McKinney. One time when they were given an inferior motel room in southern Utah, Helen remembers Ella marching right to the front office and telling the clerk, “We may look like two old ladies who can be taken advantage of, but we aren’t.” She insisted on and got a better room. Helen admired her friend’s directness and honesty: “She understands a person; she’s been impatient with me when I’ve let someone take advantage of me and has said it’s my own fault. She tells you what you need to know.”

Although Bishop Osral Allred referred to the Peacocks as “a breath of fresh air in the community” when they moved to Spring City, Ella knew many in town saw her as an “eccentric outsider,” always a “newcomer.” One home teacher told her she “should do Relief Society work and then, if I had time left, I could paint.” Despite her unconventional opinions, Ella kept her feistiness into her old age, persisting at being herself— something often hard to do in a small town—and protesting whatever seemed to her artificial: She objected, for instance, when some women re cited the adage that “every girl looks better with a curl.” She commented to a friend that the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singers looked “unnatural,” so perfectly coifed and made up. She wondered why the Relief Society women at a Salt Lake City art exhibit were smiling so much. She objected to the new lawn and trees planted on the Manti Temple grounds, “spoiling the composition—green trees and the desert mountain background; it’s not good.”

When two young women wrote a letter to the local paper The Pyramid, complaining that no one in the valley had stopped to help them change their flat tire on the highway, Peacock responded with her own letter to the editor, suggesting that drivers should be required to be able to change a tire in order to get a driver’s license. She also wrote letters to The Pyramid protesting the “distinct hazards” of pedestrians jay walking, objecting to local residents slaughtering deer in areas of new development, and calling the sarcasm in a political column “the lowest form of communication.”

She addressed her most formal and pointed complaint to the LDS church. In 1978, at the height of the controversy surrounding the Equal Rights Amendment, the LDS church spoke against it, assuring women they did not need the ERA, that it would be to their detriment. Fourteen years after she had first sought employment in Utah, Peacock’s memories of rejection resurfaced. She objected to an editorial in the Church News section of the Deseret News, entitled “The Place of Women,” that told of Joseph Smith’s advocacy for “liberty for women in the purest sense … to fully express themselves—as mothers, as nurses for the sick, as proponents of high community ideals and as protectors of good morals. What more can any woman want for herself? What more could any man want for his wife?”[3]

Some church members in the late 1970’s agreed with this attitude and some bristled at it, but most did nothing about their reactions. Peacock drove two hours to Salt Lake City to hand carry her letter of response to the Church, hoping to speak to Mark E. Peterson, whom, she understood, had written the editorial. She thought if she could “have a conversation with him, to bring things up,” she could explain herself, but he wasn’t available; instead, she was only able to talk to his secretary, who pro moted, “the glorification of womanhood, that women shouldn’t be draftsmen; they should do women’s work.”

Ella left her response to the editorial’s questions. What more could any woman want or any man want for his wife? In Ella’s opinion a lot more: “The liberty to engage in the kind of work that she is fitted for and that she wants to do.”

On moving here from the East I tried to get employment in the kind of work that I had been doing for several years and that was what I was fitted for. I was a senior draftsman, doing some design work in architectural drafting and also in pressure vessels. No one in Salt Lake City [in private firms] would even consider me, and I was told that a woman would not be hired in that field. I finally got a job because it was temporary. Was kept on and advanced from there to be an engineering technician. Why was this considered not the ‘Place of Women’? I wish I had an answer for this.

Thank you, hopefully, if you would set my mind at rest on this question.”

The task of replying to Peacock’s letter fell to Janath R. Cannon, First Counselor in the Relief Society, who told Ella she did “not know why you were not given a job by the Mormon men to whom you applied back in the 1960’s.” Cannon defended the church’s “emphasis on the value of women’s unique contributions in childbearing and homemaking” and included “some official Church statements that may be helpful.” Ella kept Cannon’s letter, but never understood these affronts because, as she often emphasized, “I could have had my choice of three jobs back east.”

That she had an abiding interest in women’s issues is evidenced in the clippings file she kept in her Spring City kitchen. Peacock was in the habit of cutting out news articles that interested her. Often she would write on the clipping, usually correcting errors in biographical information that accompanied reports of her own exhibits. In this file she also kept two news articles about Brigham Young University professors in the mid 1970’s. One told of Janice L. Tyler’s support for the ERA and another of Eloise Bell’s concern that at BYU “women were pushed into areas of Child Development and Family Relations rather than being encouraged in the areas of their interests and abilities.” Peacock also kept a clipping citing Brigham Young’s often quoted belief that “women . . . should stand behind the country, study law or physics, or become good bookkeepers and be able to … enlarge their sphere of usefulness for the benefit of society at large.”[4]

Although she was long peeved about these sexist attitudes, which were fairly common at that time in the rural states that lay between the two coasts, Peacock rationalized that “the civilization on this continent runs from east to west; it gradually crosses the continent, but the West is certainly way behind the East in women doing their own thing.” Al though she never, to my knowledge, espoused feminist causes formally, she was certainly determined in her honest reactions.

Peacock’s objections to these sexist attitudes are refreshingly straight forward. Without the “born under the covenant” mind set of women raised in the church that makes any church policy a given, Peacock questioned these practices without the guilt commonly experienced by more conventional Mormon women.

She spoke just as vociferously against what she saw as the architectural errors of the community. Once, she drove by an old house in Spring City, making a “thumbs down” gesture at the workmen about to demolish the structure, and later she returned to paint Being Demolished, one of her best works. She objected to many of the new houses built “for show” in Spring City, “probably by people kicked out of California,” and she especially admired the old Chester stone sschoolhousethat Ann and Paul Larsen dismantled and reassembled in Spring City. She admired the lifestyle of the Bennions, good friends who subsist on their land and art. She admired women who “do things,” who are productive and energetic. She valued trustworthy and supportive friends like Lee Bennion and Helen Madsen McKinney, and she honored hard work, always paying the All red children next door “like professionals,” they reported, for waxing her car or mowing her yard.

Here was a woman who seemed timeless, like the desert, as though she had always been there. Ella Peacock was so much a part of the land scape in this secluded valley, she seemed to resemble her paintings. It seemed she had come to her final resting place when she came here; it seemed right that she should finish out her days in Spring City.

But in November of 1997, on a looking trip to Ephraim, Ella became confused in her directions and could not find her way back. She was ninety-two years old and still driving her car, the gray 1988 Chevy Nova with the untinted windows, the interior splattered with the colors of her palette. A few months earlier she had confessed to me that she was driving without a license (“You won’t tell on me, will you?”), and I knew people in town gave her lots of room when they saw her car speeding down the highway. In recent years she had been fond of saying that her “forgettery” kept improving or that she felt “fine—from my neck down.” So, because she needed assistance at home and on the road, she had to be moved out of her desert element and to the east again.

She lives there today in Gaithersburg, Maryland, with her son and daughter-in-law, not far from the Washington, D. C, Beltway and half a day’s drive from Philadelphia. Now the three Peacocks live in a small apartment—the walls are decorated with Bailey and his wife Jan’s collection of nature photography—near the Shady Grove Metro stop in a tidy and carefully landscaped complex. On summer Saturdays Bailey takes Ella to nearby Walkersville in Frederick County to paint for two hours while he grocery shops. She has been dutifully working on the same painting since she arrived, a farm scene, clearly showing the east’s duller light, all the work done outdoors because of Jan’s allergies to oil paint. Ella drifts through her days, often disoriented in her son’s apartment, “without my car, you know.” Bailey and Jan attend carefully to her needs and encourage her to keep active with the task of washing the nightly dinner dishes. During her first month in Gaithersburg, when I asked if she was still painting, she said, “Yes, but it’s too green here.”

Editors note: Ella Smyth Peacock passed away on June 27,1999. She was 94 years old.

[1] This essay is based on numerous interviews I have conducted with Ella Smyth Pea cock since July of 1987. Interview notes and photocopies of various documents are in my pos session.

[2] Ordained in 1918, excommunicated in 1943, re-baptized in 1954.

[3] Deseret News, 11 March 1978, Church News section.

[4] Journal of Discourses

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue