Articles/Essays – Volume 36, No. 1

Endowing the Olympic Masses: Light of the World

Refashioned beyond recognition, Salt Lake City hosted the Winter Games in February 2002. While the world partied Olympically—Budweisers in hand, whooping it up in chaotic street fetes—Latter-day Saints found haven in the LDS Conference Center. With its open door and rich collection of cultural arti facts, the center functions not just as an auditorium, but arguably as the Latter day Saints’ first cathedral, with side “chapels” designed for devotional and historical art and architecture, and deeply symbolic fixtures, from doorknobs and seat upholstery to windows and waterfalls. The new building is not only an ecclesiastical seat, as in traditional cathedrals, but also a multi-use common where Mormon and non-Mormon can potentially converse with the highest values of the Mormon community.

It thus seemed especially appropriate that this was where the church offered to visitors Light of the World, a theatrical extravaganza of filtered light raining down and flying up. Yet most of the audience (at least on the night I saw the show, February 13), seemed to consist of Mormon families and church youth groups, despite the best efforts of the efficient box office to recruit out-of-towners by putting them in the short, fast-moving line, after asking for identification.

More than a pageant and somewhat less than a traditional book-musical, Light of the World is best described as a truncated endowment ceremony for the masses. Its presentation proved to be less an ecumenical offering than a mirror to church members anxious about their place in a world perceived as indifferent to them at best, hostile to them at worst. In the 21,000-seat auditorium, the early narrative—if not the actual ritual—of the temple endowment was presented commercially, perhaps heralding a first step toward lifting Mormon temple worship out of the “religious pornography” in exposes like The Godmakers and into the public realm of sacred texts, where I believe the endowment belongs.

In the show, familiar temple tropes were everywhere. A seventy-foot, floor to-ceiling drape hung front and center of the stage, reminiscent of the mighty temple veil which symbolically separates humanity from the presence of God. This time, however, the gauzy white surface was a screen upon which striking, high-resolution images of galactic space (borrowed from NASA’s Hubble tele scope) undulated. These were followed by images of the creation, including the “firmament,” plant, and animal life. Such use of the temple veil would otherwise have been a desecration, but here (ostensibly for the benefit of Olympic visitors) Mormons likely saw it as an accommodation to the world, a Disney-esque light show mixed with the book of Genesis. When the veil was penetrated (or more accurately, raised), we learned this was indeed a veil separating God from man, but not the one through which signs and tokens are given in preparation for celestial rest. Instead, this represented the first veil drawn, in Mormon theology, over the memories of spirits as they are born to earth, which appeared suddenly before us as a 130-foot domed stage.

The semiotics of Light of the World are pure Mormon genius. The show presented metaphysics as simply metaphor by rewinding and compressing temple iconography for the public. The effect was both high-voltage spectacle and—as in other Mormon outings of this type—theologically obtuse. To a tribal Mormon like myself whose last temple recommend bears a decade-old expiration date, Light of the World might have been seen as a corroboration to the account of Time magazine reporter Terry McCarthy, who, on his way into President Gordon B. Hinckley’s office to interview him, said he felt like he was in a David Lynch movie, as if “one has been dropped into the middle of a plot, without knowing the beginning or the end.”[1] Jack Mormon that I am, the show made perfect sense to me.

What McCarthy didn’t know was that Joseph Smith’s “restored” understanding of God’s plan for humanity does have a plot. This is true both in Plato’s causal sense as well as E. M. Forster’s, who distinguished story, which arouses only curiosity, from plot, which requires intelligence and memory.[2] Knowing life’s overarching plot in detail is one thing that defines the Latter-day Saint. For this reason, Light of the World encoded the journey of the human, not as a simple picaresque, but as a plan, or plot, driven on high by the glory of God.

The oath-giving endowment, which takes place exclusively in the temple, is more obliquely known outside the House of the Lord as “the Plan of Salvation” (or “the Plan of Happiness” in post-Madison Avenue Mormonism). This, coupled with the first and most public part of the endowment ritual, is what was dramatized through the secularized veil at the conference center. The show, whose title comes from the Gospel of John, was an airbrushed version of “the plot,” complete with thunderous folk dances, the Tabernacle Choir, a giant storybook, big screen projections, and actors flying on wires as high as seventy feet.

Subtitled “A Celebration of Life,” Light of the World was hard to follow because of its myriad diversions, but the church provided a slim, full-color, foldout program deftly designed to function for the audience member as pull quotes in a magazine article do for a reader. Section headings followed the Plan of Salvation, sans both church ordinances and the doctrinal lingo common to traditional proselyting materials. This tack was not unlike Stephen R. Covey’s sly cooption of LDS principles in his Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, which the New Yorker once called “charmless and absolute”[3] while comparing it to the baffling rhetoric of Newt Gingrich. Unlike the brainchild of Covey, Light of the World was all charm. It was also surprisingly non-absolute in ways that could mean a broader definition of what Latter-day Saints can think, say, and do, and still be considered one of the rank and file.

For example, the term “light” replaced “plot” or “plan,” a brilliant re-imaging of Book of Mormon doctrine which grants the light of Christ, or conscience, to all human beings regardless of belief. Despite the change in terminology, life’s phases—the plan—are performed on stage and even listed in the program: birth, discovery, adversity, achievement, and finally, testimony.

To the late Elder Bruce R. McConkie, a testimony was one’s encapsulated belief, the expression of which could only be based on a handful of specific restoration tenets. But in the Conference Center show, testimony was defined as God’s “light [which] gives meaning to life.” Perhaps this re-reading of testimony suggests that Latter-day Saints are not incontrovertibly beholden to McConkie who, as an apostle, not so much suggested certain definitions of Mormon terms, as insisted on them. Indeed, if word gets out that testimony can refer simply to the meaning that God’s light gives life to earth, a broader, more shaded Mormon identity—one that is in conversation with, but clearly separate from, the corporate church—may be close to emerging. This is a development I champion because it would, in my view, be invigorating not only to the individual but also to the institution.

The co-directors of the 1,500-cast show were the ones responsible for its text, which shared temple knowledge with non-Mormons and allowed for different interpretations of notions like testimony. Randy Boothe is a Disney consultant who has been associated for years with the BYU Young Ambassadors, and Light of the World has the toothy, polished, tingle-and-Wow! of those globe trotting performers. But it was the show’s writer, David T. Warner, the fiercely talented eccentric from my youth, who was the mastermind behind the fusion of temple worship, multi-ethnic spice, and Olympic jingoism. As the division head for the church’s music and performing arts, Warner has an uncanny eye for which on-ramps are necessary for a church determined to be a part of the world’s superhighway of mediated messages. He also knew that the rounded earth stage—veiled or unveiled—passed as a giant fish bowl wherein powerful lighting hid as much as it revealed Mormon parameters to the world, but most importantly, to Latter-day Saints themselves.

Pioneer heritage is not only the bedrock, but the driving ethos behind what Latter-day Saints feel is their mission: to colonize the world. So it was no surprise that the most moving moment of the show was when the stage dome cut away like a horizontal door while actors, knee-deep in fog, staged the heroic efforts of three eighteen-year-old boys who carried on their backs each of the stranded handcart pioneers caught in a freak storm at Wyoming’s Sweetwater. In the alchemy of the Mormon mind, expressed sentiment of church history often changes into a spiritual witness that, not only is the church true, but so is the Latter-day Saint who aligns him or herself to it faithfully. If the Plan of Salvation defines Mormons, it is loyalty to the collective which is their litmus test. Joseph Smith’s highest virtue, as he demonstrated, was an unflagging commitment to himself, the prophet, as well as to the body of believers.

Besides pioneer heritage and institutional loyalty, Light of the World also pulsed with the relatively new prescription of Christ as center. But like the fusion of individual to institution which I believe is common in the LDS church, Latter-day Saints apparently cannot separate Christ from their corporate church as do traditional Christians. So while the LDS church is in over-drive to prove it is Christian, it has positioned Christ as a sanctifying code of the church, a code one can hear intoned over and over—irreverently, it could be argued—in a walk through the new Temple Square Visitor Centers. His name is not only the re quired imprimatur placed at the end of prayers and sermons, but also the bold face print on the church’s new logo, the necessary nod to Christian America so that the work of God can move forward.

To be fair, the central role of Christ has always been a presupposition for Mormons, as it was in nineteenth-century frontier America. But for today’s Latter-day Saints, it is the great work bolted to the institution—which is far more than an institution to them—which is “of the essence.” Christ does not seem to figure, for most Latter-day Saints, as the be-all-and-end-all, the deity incarnate celebrated by the apostles John and Paul.

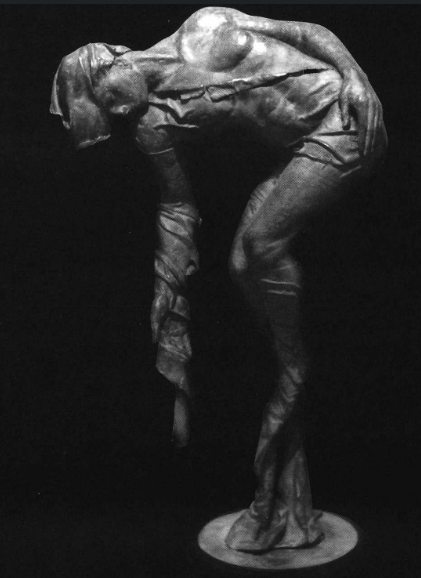

This was what lay uneasily in the shadows of Light of the World, in the darker corners of the earth orb where I believe Mormons still struggle like half molded clay. Yet the show trumpeted the more devotional message of traditional Christianity, a reassurance embodied in the four-story projection of the Christus statue rising above the stage, the warmth of its bare chest between slightly up raised arms embracing the stage earth. Though the symbols intimated a personal Savior whom devoted disciples adore, the Mormon Jesus came across as a curious mix of Christ-as-code word and Christ-as-the Newtonian god who created the world like a finely tuned watch before its gentle launch into the universe. The Son of God, as corporate mascot, leaves the industrious Saints to carry on the work. I believe Latter-day Saints are stuck under these constraints, as were the early Jewish Christians during the first three centuries A.D., between being a variation of an established religion (Judaism) and a completely new one (Christianity).

This “stuck-ness” was borne out by the sudden appearance on the stage near show’s end of a giant projection equal in size to that of the Christus—of President Gordon B. Hinckley. “That which is of God is light,” he quoted for us, “and he that receiveth light, and continueth in God, receiveth more light; and that light groweth brighter and brighter until the perfect day.” The aging prophet seemed almost bashful in his warmly wrinkled way, but pleased. The living prophet—not Christ—is the head of the corporation and the resident gnosis of this great, shining cathedral, wherein the story of man’s search for happiness is told, however carefully, however commercially, for the world. As the veil with its projections of outer space closed in, quieting the teeming earth inhabitants in their colorful, ethnic garb, there was a collective sigh in the largely Mormon audience. The prevailing sentiment was that when the 1.5 million Olympic visitors leave Zion, there will be even more work to be done. But who will they be as they put their “shoulder to the wheel”? Are the good works of the kingdom—with a nod in the direction of Jesus—the only thing that proves someone is a Mormon?

“The games will come and go,” reported the Los Angeles Times at the close of the Olympics in February 2002. “Then the people can return to the. . .truly important work that gets done in some shape or form in every city. They can return to defining themselves.”[4] The city of angels knows something about shaping an identity, having hosted the games once themselves. Until that “perfect day,” civic identity in the Saints’ holy city will always be tied to what Mormons think of themselves, to what they are allowed to think of themselves, and to the open spaces wherein individual believers find expression—open spaces like Light of the World, in which re-interpretation of dogma seems to have tentatively reared its head.

[1] Terry McCarthy, “The Drive for a New Utah,” Time, 11 February, 2002, 58.

[2] C. Hugh Holman, ed., A Handbook to Literature, 4th ed. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1980), 335.

[3] David Remnick, “Lost in Space,” New Yorker 70, no. 40 (5 December 1994): 84.

[4] “The World Watched,” The Salt Lake Tribune, 28 February 2002, A7.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue