Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 4

Enduring

Edgar to Gloucester in King Lear:

Men must endure

Their going hence, even as their coming hither.

June 1982

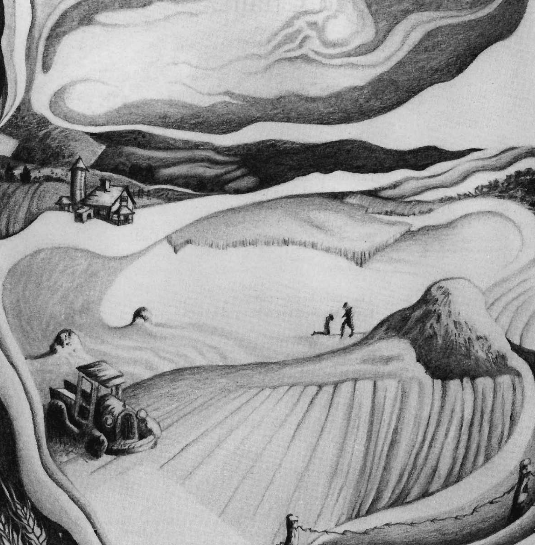

I grew up in a safe valley. The years five through twelve, when we are most sensuously attached to the landscape and when, I think, the foundations of identity are firmly laid, I lived in gardens and wheatfields. They had been claimed a generation before from desert knolls and sagebrush flats but were now constantly fruitful, watered by canals or sufficient rain for dryland grains and surrounded by low mountains that were protective, inviting, never fearful. We hiked into the mountains for deer and trout to supplement our meat, eaten sparingly from the pigs butchered each fall, or sometimes we rode out to look for horses that had strayed and, once a year, on the Sabbath nearest the 24th of July, with all the Sunday School, we went in cars to have classes out of doors and eat a picnic together and explore those safe canyons of Cherry Creek or Nine Mile that brought us our water.

Even when I found a perfect flint arrowhead and a large flawed spearhead on one of those picnics, I did not imagine the blood. Instead I thought about coming there to live in a rock cave I had found high in the canyon—perhaps with Dee Christiansen, my companion in Saturday-long Tarzan adventures, perhaps with Margene Ware, my first serious love (moral and practical details absolutely did not intrude into such fantasies).

I wanted safe and secret places even within that safe valley. And I found or made them. The canal was one. It moved slowly along the east side of the valley, no more than two feet deep except at “The Diversion,” where a falls as the canal divided created a spice of danger. Submerged in the rich muddy water with a straw for air or lying on the farm road bridge while it seemed to move backward over the surface flowing just a few feet below, my mind would flow to a safe world inside me.

There was the vacant lot across from Grandma Hartvigsen’s that grew pepper weeds three feet high, dense and fragrant, perfect for making trails and hidden nests. The cottonwood that stood right at the corner of Grandpa’s barn and could be reached from the roof had a large cup where the first branches separated. And there was a little grove of fruit trees, part of the old homestead out on what we still called the Coffin place. My father relentlessly consolidated those early 160-acre holdings, each with log cabin, a well, outbuildings, and trees, into large, uninterrupted fields to fit the economies of the shift from horses to tractors. This grove was not leveled partly because it was watered, along with a lovely line of cottonwoods, by overflow from the town reservoir, built on our northern boundary to hold the stream from Nine Mile. Dad kept Peter Coffin’s old house and barn to store machinery in and we always parked the truck there and ate our lunch in those trees on that fresh, grassy bank, adding watercress from the little overflow stream and sometimes plums or apples from the neglected grove.

The subtlest bliss from such safe and cozy places came each spring. It was a bliss mostly of the mind because I could only be in such a place occasionally and briefly—but my heart yearned, on early May mornings, when the brisk Southern Idaho wind still moved the tops of sagebrush along our fencelines and I could look down as we passed in the truck and see, among the clumps of sage, small patches of last year’s dead grasses with just a scatter of new blades and a few small flowers coming through. I knew those places were warm and fragrant, humming with tentative insect life.

When I would sometimes, on a Saturday, walk out to the “ranch” (as we called it, though any livestock that might justify that name were gone), carrying an extra dessert for Dad’s lunch or a hoe to work at the potato patch we planted during the war by a spring in the lower 320, I could sometimes stop and hide for a time under the sagebrush out of the wind. I could crush the small gray-green, velvet leaves from the strangely dead-looking branches until the air was sharp with sage or hold my fingers close until the smell went back into my throat. There would be one or two mild yellow buttercups, with five waxed petals, concavely shaped as if still ready to close quickly around the orange center. And by late May a few wild honeysuckles, the blossoms washed pink and detachable, made to be plucked off delicately and delicately set between the lips so the tube under the blossom could be sucked for the smallest, most delicate taste, deep on the tongue.

But most of all I was drawn to secret places I made, like the huge lilac clump at Dee’s grandmother’s, where we had cut out the inner branches for our hiding place and could strip to our shorts, creep out and run wild across the lawn and garden, through the barns, and even sneak into her cellar for a can of tuna fish and retreat through branches to lie still as she walked by, calling Dee. Or the places I fashioned at the back of our woodpile where I could be completely hidden and watch crazy old Brother Nelson do his chores, mumbling passages of scripture to himself, and where I hid the revolver a friend, who had stolen it from home, gave me to keep. I would nestle in among the logs and boards, hold the gun in both hands and think about using it to kill deer when I took my mate off to Cherry Creek. One day it was gone.

Our valley began just outside the rim of the Great Basin, at the point we called Red Rock, where the waters of ancient Lake Bonneville had once worn through the Nugget sandstone formation and drained out into what became the Portneuf and Snake rivers, leaving a mile-wide scar and finally a slough moving slowly through cattailed bottom lands that gave us our name, Marsh Valley. The slough provided poor fishing—mostly chubs and suckers—but attracted great flights of geese in the fall that swept up to our stubble fields to feed at night and moved to the north in huge, constantly reforming wedges. I may have sensed from them that our valley was part of something larger, but surely I knew so when my parents suddenly went off forty miles to Pocatello late one night in Grandpa’s new hump-backed Mercury, leaving me in Grandma’s care, and came back after a week with my baby sister. Or when I sat in Grandpa’s lap, playing with his gold watch chain and listening to the strange, emphatic voices emerging from the static of his Philco. Prophets, I was told, at general conference in Salt Lake City. But even the Second World War seemed far away, unconnected, intruding only for moments when I rushed outside at a sudden roar one overcast morning to see a strange, double bodied, P-38 fighter plane just passing over our house, hedgehopping down the valley toward Pocatello under the low clouds. Or when the oldest Bick more boy was shot through the chest by a sniper on Okinawa and came home to tell about it in Sacrament Meeting.

Hamlet to his friend:

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

But come—

My father knew of larger things than our valley, and he included me easily. He had left home at seventeen, learned to paint the fine interiors of Union Pacific passenger cars, and lived alone, rising early to read the Book of Mormon and The Discourses of Brigham Young. When he spoke of Nephi and Alma and Moroni or of Joseph and Brigham and Heber I felt his love for me. When he said Christ had appeared to him in a dream and told him the Book of Mormon was true, I knew it had happened. And as I rode with him to do his share on the Church’s welfare farm or to the store or the wheat elevator or the machinery shop or from neighbor to neighbor, to borrow and return, to ask for help and give, to buy and sell, I saw him doing the truth and felt safe.

One June dawn we drove toward the reservoir farm for a day of weeding the fallow ground. He would drive the tractor. I was old enough to ride the twenty-four-foot rod weeders, jumping off to tromp away stubble as it accumulated around the goosenecks and rods. That morning, as he often did, he stopped the truck and took me to see how the wheat was heading out in that lower 320. We kept our feet between the rows as we walked out on a ridge, I just learning how to imitate his motion of plucking a stalk to examine critically its forming kernels. He asked me to kneel with him, and he spoke, I thought to Christ, about the wheat. He pledged again, as I had heard him at home, to give all the crop, all beyond our bare needs, to build the kingdom, and he claimed protection from drought and hail and wind. I felt, beside and in me, something, a person, it seemed, something more real than the wheat or the ridge or the sun, something warm like the sun but warm inside my head and chest and bones, someone like us but strange, thrilling, fearful but safe.

How is it then that sometime in those years I first felt my own deepest, most hopeless, fear, the fear of being itself? It is a fear I have never been able to write about until now nor imagined anyone else knew about or could under stand, a fear so fundamental and overwhelming that I feel I must literally shake myself from it when it comes or go mad. And yet I felt it as a child in that safe valley. I’ve forgotten, perhaps blocked away, the time it first came. Probably it was during one of those long summer evenings when Bert Wilson and I would sleep out on our large open front lawn and watch the stars come. The stars in that unpolluted sky were warm and close and dense and, as I began to learn from my father, who taught early morning seminary, about the worlds without number God had created and that we had always existed and always would, destined to explore and create forever in that infinite universe, it was exciting, deeply moving at times, to look into those friendly fires that formed patterns in the night and stretched away beyond my comprehension.

But one evening there began to come moments when I could feel moving into my mind, like a physical presence, the conviction that all was quite absurd. It made no sense at all that anything should exist. Something like nausea, but deeper and frightening, would grow in my stomach and chest but also at the core of my spirit, progressing like vertigo until in desperation I must jump up or talk suddenly of trivial things to break the spell and regain balance. And since that time I am always aware that that feeling, that extreme awareness of the better claim of nothingness, lies just beyond the barriers of my busy mind and will intrude when I let it.

Much later, of course, I learned about existential anxiety and the Christian sense of total dependence, of contingency, and I heard about the question Paul Tillich’s daughter asked him, “Why is there something and not nothing?” But I believe these are quite different things from what I feel. My own deep fear seems unique, precisely because of those unique Mormon beliefs that have given me my greatest joy and security. It is one thing to wonder, as traditional Christians do, why an absolute, perfectly self-sufficient God would bother to create me and this strange, painful universe out of nothing, to feel the proximate mysteries of this “vale of tears” but also an utter dependence on an ultimate being who can indeed reduce me and the universe to nothingness and thus painlessness again—or to feel Albert Camus’s desperate bitterness about a universe that has produced beings like us, with our constant yearning for meaning and permanence, but which seems to answer with absurdity and annihilation.

My own experience with God and this universe has produced not only dependence but identity. I have felt confirmed in my own separate, necessary, and unquenchable being. I had no beginning, not even in God. And the re stored gospel provides the best answers—the most adventuresome and joy ful -— to the basic questions about how I came to be here and about my present and future possibilities. But there finally is no answer to the question of why and how I exist in my essential being. I just always have, and that is where my mind balks in horror, perhaps at its own limitations. I just cannot imagine how it could come to be that there is existence or essence—how there could be something instead of nothing. And the answer of Joseph Smith, that it did not come to be but simply always was, is marvelous—until I let the horror intrude.

Joseph Smith to the family of King Follett:

All the minds and spirits that God ever sent

into the world are susceptible of enlargement.

I know a young couple whose two-year old boy, because of cerebral palsy, is a spastic quadriplegic, apparently blind and deaf. His twin brother is perfectly healthy. As a new high councilman, I gave a sacrament meeting sermon at my assigned ward on the grace of Christ, his unconditional love for sinners. Susan, the mother, came up, grateful for what I’d said and wanting to talk more about how she could cope with her struggles and feelings, her guilt about her son. What neglect had caused the fever in the hospital that produced the palsy? Or, if a genetic “accident” was to blame, why had God allowed—or caused •— it? Why had priesthood blessings that promised recovery not yet been fulfilled? How could she go on holding Allyn almost twenty-four hours a day to keep him from bracing back and choking? How could she be forgiven for her anger at him, striking him, sometimes wanting him dead? I felt she needed most to rest and offered to hold Allyn while she had an undisturbed Sunday School hour with her husband. Then we talked later in the afternoon.

I wasn’t much comfort. I could testify about Christ’s understanding and unconditional acceptance of her and about the real benefits to her son of gaining a body, however imperfect now, and of feeling her love while he lived, however dimly. But I could not tell Susan I found Allyn’s trouble a blessing in disguise or evidence he was an especially righteous spirit who had volunteered for such trouble or that he would be compensated in some extra way in the next life—that is, beyond the marvelous opportunity to grow and be tested in a normal body during the millennium. She listened, wept, disagreed, accepted some things. I offered our family to care for her twins occasionally so she and her husband could get away to rest and to renew their own relationship, which had, she said, suffered.

Recently in her sacrament service, I heard Susan sing “I Walked Today Where Jesus Walked” and more recently I heard her give a Spiritual Living lesson in Relief Society on apostacy, talking forthrightly about her own struggles with personal apostacy when priesthood blessings seemed to fail and when she felt unacceptable to God and unable to continue to endure. She warned her sisters to constant vigilance. I feel warned of two things: that holding little Allyn while Susan has an hour with her husband is at least as important as my words were and that she sings and teaches and bears her testimony more maturely and movingly now—and also continues to suffer while she endures.

In an interdisciplinary colloquium for freshmen I teach with four col leagues, I’ve been learning about genetic problems that produce malformations in children. As the sex cells divide, the complicated process of meiosis, by which the chromosomes are reduced from forty-eight to twenty-four, some times produces broken and reattached parts—translocations—or duplications in some eggs and sperm cells and, of course, missing or partial chromosomes in their divided opposites. Many of these accidents (statistics all nicely predictable) are lethal, resulting after fertilization in miscarriages or still births, but some produce living children. Down’s syndrome children are the result of such translocations, but there are also many others, rare but real, hidden away from our usual experience. The frequencies are surprising—1 in every 700 births is Down’s syndrome (now being called trisomy 21 to clearly identify the problem and the chromosomes—a duplication or a segment attachment to chromosome number 21, making it “three-bodied”). Jean de Grouchy’s Clinical Atlas of Human Chromosomes, which is amply illustrated with photographs of the victims of chromosomal aberrations, is a kind of chamber of horrors of deformed, doomed children: cleft palates in Patau’s syndrome (1 in 5000 births), impossible flexion deformities in Edwards’s syn drome (1 in 8000). In some texts a refrain comes at the end of each description: “the mean survival time is about 2^2 months, 90 percent of all cases dying within a year” of birth, or “mean survival 3 months, 80 percent dying in the first year.” Is it a relief to know that most such terribly deformed children do not live long? But some do, with retardation, shortened, skewed limbs, grotesquely positioned fingers and toes, clubfeet.

The sex chromosomes, X and Y, most commonly cause abnormalities through duplications, though a missing X in females produces Turner’s syndrome: tiny body, sterility, low mathematics IQ, webbing on the neck. An extra X in men produces Klinefelter’s syndrome: some female body characteristics, sterility, low verbal IQ. Extra X’s can occur up to six, producing lower and lower IQ, but perhaps most trying to a believer in moral agency is the single extra Y in men, which produces a tall, powerful body and impulsive behavior that easily becomes anti-social. Victims of this chance occurrence in cell division (1 in 1000 births) have forty times the chance of others to end up in a penitentiary.

One syndrome, designated 5p monosomy (a missing part of chromosome 5), produces some facial and bone deformations and very severe retardation but not high fatality. Its deformation of the larynx produces a distinctive cry, like that of a kitten, which gives the syndrome its more common name, “cri du chat”—cry of the cat. What do parents endure when they first hear that cry from their newborn—and then as the years go and the cry diminishes and a characteristically wide-eyed, almost jawless face develops in a child who will live long, without language, with an IQ under twenty. If the figure 1 in 50,000 births is right there must be over 4000 sets of such parents in this country, perhaps 80,000 in the world.

A few months ago we read, with surprising calm it seems to me, of the parents in Bloomington, Indiana, who were able to get medical and legal sup port for a decision not to perform the difficult but feasible surgery needed to save their Down’s syndrome child—designated “Infant Doe.” Their lawyer called it “treatment to do nothing.” Columnist George Will called it homicide. Since the case apparently would not have been filed—probably not allowed— if the child had not had Down’s syndrome, the logic of the decision suggests that parents have the right to kill through neglect—and why not more directly?—a child that they decide is a huge trouble. And surely, then, it would seem society must have the right to relieve itself of those who come to us through “wrongful birth,” the tortured phrase that has developed in recent litigation aimed at doctors whose advice or decisions leads to safe delivery of severely deformed or retarded babies who could have been aborted. So far the courts have been willing only to assess the doctors the costs for care of such “wrongful births”—not to establish punitive damages.

I know of a couple whose first baby was born with a gaping cleft lip, the eyes squeezed almost into a cyclops, no muscle tone, and profound retardation. It lived ten days, requiring very expensive care at enormous cost to the parents. A chromosomal check available in recent years revealed the mother to be a carrier of trisomy 13, Patau’s syndrome, and the doctors presented the options: no more children except by adoption, amniocentesis in future pregnancies to check the chromosomes of the fetus and abortion in case of abnormality, or having children with a high percentage of carriers and abnormalities. On the basis of their opposition to birth control and abortion (and thus to amniocentesis that would assume abortion as an option), and with faith in an optimistic priesthood blessing and strengthened by the fasting of their ward and stake, the couple went ahead with another child. It was born with trisomy 13, lived thirty-three days, and put the parents in debt over $100,000.

Jesus Christ to Joseph Smith:

Fear not even unto death; for in

this world your joy is not full,

but in me your joy is full.

A year ago while we were in England, Charlotte learned that her mother, Josephine Johnson Hawkins, had cancer of the pancreas. There was an exploratory operation. The decision was not for the dangerous surgery or traumatic chemotherapy that had little chance of helping but for a peaceful final few months. When Charlotte came home in July she found her mother wasted but still hoping: she had had a blessing, she said, that she would recover. Charlotte decided to do what could be done, found a doctor willing to do limited chemotherapy, brought her mother to her own bed (I moved to a cot in my study), and together with her sisters set about making Josephine well. They cooked tempting food to keep up her appetite against the nausea of painkillers, bathed her, and helped her to the bathroom (finally carrying her) to avoid the discomfort of bedpans. Charlotte was determined and the doctor encouraging until one day in late August when he saw that the chemotherapy was just not working and stopped it. Josephine told me she thought she could have the faith to make the promise work, but there was so much pain and she was so tired. Charlotte kept trying, fiercely believing in the promise, hoping. Our daughters lay on the bed with Josephine, held her in their arms and talked about canning apricots with her years ago. She died on October 2. The last month she slowly turned a deep golden color from the jaundice.

I have long thought that Josephine Hawkins took too much onto herself, keeping her own hurts inside, interceding for others in potential conflicts, absorbing others’ weaknesses, letting any damage be done to her feelings, let ting mercy rob justice. The internal stress she invited may well have brought on her cancer and killed her, and I felt for a long time she was foolish. But I decided in that last month that she was right. And she was also right about jokes. She never could get the punchlines straight and always marred a funny story in the telling so that the humor came against herself, rather than who ever was the butt of the joke. I used to be condescendingly amused, merely tolerant, but I’ve decided she felt intuitively that nearly every joke is at some one’s expense. She took the expense. I think she was right to do so, whatever the cost.

Since last fall Charlotte hasn’t slept well. She wonders about that promise to her mother and about fighting to hold on so long, prolonging the pain, straining her bonds with her sisters. And she takes the children’s troubles more onto herself and doesn’t tell jokes very well.

Christ describing the last days to his apostles just before leaving them:

Then shall many be offended, and shall

betray one another, and shall hate one

another. And because iniquity shall

abound, the love of many shall wax

cold. But he that shall endure unto the

end, the same shall be saved.

On 13 May 1981, an attempt was made on the Pope’s life at his public audience in Saint Peter’s Square. I was in the throng, next to his car, just reaching out to touch his hand. My mind formed clearly two partly visual, mostly verbal images: first, John Paul II, a man of God, is shot, hurting terribly, will die; and second, Poland’s Solidarity, which this man inspirited, and Lech Walesa, to whom this man conveyed symbolic spiritual power, are finished. When I learned that night on the train away from Rome that the Pope had survived I knew it was a miracle—for him and for Poland. I learned of another miracle in the summer when the Polish military leaders, by refusing to use force against fellow Poles, apparently prevented the Communist Party from destroying Solidarity. In the fall I began to wake in the night and think about the coming winter. With Poland’s economic problems still unsolved because of the continuing power struggle, I knew that hunger could defeat Solidarity. Food riots could justify internal suppression or external intervention. Another miracle was needed. Those images of the Pope and Walesa returned. I couldn’t sleep.

Finally I began to explore. I found that most people felt deep concern and admiration for Solidarity and wanted to help but didn’t know how. Agencies like Catholic Relief Services and Polish National Alliance were sending food but not enough and were not doing large-scale publicity that might attract help from non-Catholics and non-Poles. Through Michael Novak, a Catholic lay theologian who had met in Rome with Solidarity leaders, I was able to get in contact, by phone to Warsaw, with Bronislaw Geremek, chief advisor to Solidarity. He said the children were starting to die of dysentery. He asked that we send dried milk, detergents, and technicians to help them build privately controlled small businesses and that we do it soon, by plane. We organized Food For Poland, a non-profit public foundation for tax-free contributions and had a planeload of food and arrangements almost ready for donated flight when martial law was declared December 13.

All flights were grounded. Geremek was one of the first arrested (I saw his name on a list in Time on Christmas day) and from a letter smuggled out later we learned he went on a hunger strike in January and then was punished with an unheated room. Our government cut off its aid and vacillated on private aid like ours. We weren’t certain food would get through. Finally it became clear through messages from Poland and successful shipments from Western Europe that the military was not interfering; our State Department gave approval and on January 6 we sent our first shipment, by truck, then train and Polish ship to Gdansk. Since then we have sponsored a National Day of Fasting, made five more shipments of food, medicine, clothing, deter gents, and sent one of our trustees along with one plane load to Warsaw to verify first-hand the proper distribution to those most in need. Our national director went a few weeks ago to Gdansk to observe distribution of our largest shipment, which included 90,000 pounds of milk from the LDS Church.

We have been responsible for adding perhaps $1 million worth of supplies to the Polish Relief effort. That is pitifully little—the equivalent of one extra good meal for the three million Polish children, aged, and families of imprisoned Solidarity members who are in greatest need. Our government cut off $800 million in aid just for this year. And I am convinced that perhaps twice that much, invested one year ago in a massive Marshall Plan to Poland, focused on improving farming efficiency and on building small privately controlled industries and businesses, would have provided enough economic resurgence and enough return to Poland’s traditional productivity to enable Solidarity’s nonviolent success and a gradual development of basic freedoms. But now the stalemate drags on. Someone tried to kill the Pope again, one year later, this time with a bayonet. Poland is not in the news, and people don’t think much now about helping.

During January and February I woke very early each morning, thinking of the mistakes I was making as an English professor trying to raise funds, the missed opportunities, inept public relations—not enough hard-nosed pushi ness, not quick enough tough-minded assessment of how we were being used by others to their own advantage. I thought of the people I met each day or talked to on the phone who could give $1 million easily but didn’t, or the families who fasted and sent all they could, but only once, or students and faculty who helped a while and then disappeared. And I lay awake thinking of Bronislaw Geremek in his cold cell, of thousands of families with father or mother or both interned or dismissed from jobs -— knowing we were failing them. I thought of a film I saw in December made by a French journalist of an interview with Lech Walesa held just a few days before the December 13 crackdown. Walesa sat holding his daughter, with a portrait of John Paul II in the background. He said, “I must remember that even if my dream of a free Poland is achieved, it could be taken away in a day. Disaster can come anytime, as it has in the past. I must be ready for death. I could die at any time and must be prepared while I continue to work.”

Recently we’ve decided we may have to discontinue Food For Poland before long. We’ve failed to get major corporation or foundation support or the help of a popular entertainment figure—both of which seem necessary to keep up momentum. And I am ready to admit I do not have the gifts—or the stomach—to make a career of fundraising. I do not lie awake much any more. When I do it’s usually to hold Charlotte, who sometimes has bad dreams. We get up very early and, as the days begin to shorten, play tennis for a half hour in the cool shadow of Y Mount.

And for the first time in over a year I’ve begun occasionally to let the fear of being slip into my mind. Sometimes I look up from a book or the type writer and the world is only whirling quanta of energy, reflecting all its seduc tive impressions of color from a palsied and blank universe. If I let it (some times I invite it), the horror deepens, because neither that atomized, inertial, spinning chaos nor my strange ability to sense and order and anguish over it have any real reason to exist. I want to take refuge in the mystery that an absolute God made it all out of nothing and will make sense of it or send it back to nothing, but Joseph Smith will not let me. There must be opposition or no existence. Is it more difficult or easier to take my problems to a God who has problems?

Nephi bidding farewell to his people:

If ye shall press forward,

feasting upon the word of Christ, and endure

to the end, behold thus saith the Father:

Ye shall have eternal life.

Postscript: December 1982

In September, at the equinox, I was called to be bishop of a newly formed student ward. I have stewardship of 120 young couples, most already beginning to have children. The first thing the Lord told me, when I began to think and pray about staffing the ward, as clearly as I have ever been told anything, was to call Susan as my Relief Society president: to be in charge of all the women, their religious instruction, their compassionate service, their sisterhood, their training as wives and mothers. It made no sense: Susan was still burdened greatly by her struggles with Allyn, with her husband, with herself. Dale had left school to cope with their enormous financial burdens and was planning to move them to Salt Lake. But the call was clear and they accepted.

Susan immediately visited every family and established the crucial foundation for making a ward community. She has opened herself and her life entirely to her sisters and conducts all her interviews, her meetings, her casual conversations with the same absolute honesty and down-to-earth forthrightness. The women—and their husbands—experience quite directly the struggles, the ups and downs of anguish and hope, the need for help, and the enduring courage through which she lives day by day.

I’ve tried to be that open and direct as a pastor. I speak for a few minutes in nearly every sacrament meeting, very personally, about the realities of my life with Charlotte, our sorrows, our decisions, our faith, and I teach the family relations class each Sunday for all the newly weds in the ward. I spend many hours with people in trouble: couples who have hurt each other until they can’t speak, lonely husbands, burdened with past sins and present insecurity, women who can’t have children, and women who are having too many. I talk about the problems Charlotte and I have had, how we have hurt each other and suffered and learned and got help and endured. How the Lord has directed us from place to place across the country—toward unforeseeable service and learning and away from ambition for luxury and prestige. I call people to the regular positions but also to special assignments: a couple to help take care of Allyn in sacrament meeting, another to work with an alcoholic living in our area separated from his family. I see people changing, marriages beginning to work again, people helping without being called, people making moral decisions—to pay income tax on tips from years back, not to sue some one who has wronged them. I see Susan, now three months pregnant, smiling often.

Reality is too demanding for me to feel very safe any more in the appalling luxury of my moments of utter scepticism. God’s tears in the book of Moses, at which the prophet Enoch wondered, tell me that God has not resolved the mystery of being. But he endures in love. He does not ask me to forego my integrity by ignoring the mystery or he would not have let Enoch see him weep. But he does not excuse me to forego my integrity by ignoring the reality which daily catches me up in joy and sorrow and shows me, slowly, subtly, its moral patterns of iron delicacy.

Food For Poland has continued. We have been accused of glory-seeking, of being liberals indulging in do-goodism instead of the true religion of doctrinal purity, and by some of being traitors: giving aid to the enemy in time of war. But we are sending, in cooperation with the LDS Welfare Program, another large shipment of food and clothing to help the Poles through this winter. Charlotte’s father, after a year of trying it alone, will be coming to live with us soon. Our third daughter, who was born with a diaphragmatic hernia and who almost died from a resulting intestine block last June, while she was on a mission—came home, was operated on, slowly recovered, and is going back into the field in January. Our oldest daughter is in love. I lie awake sometimes now, as the nights begin to shorten, my mind besieged by woe and wonder.

Edgar to his blind father in King Lear:

Men must endure

Their going hence even as their coming hither.

Ripeness is all. Come on.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue