Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

Ethnization and Accommodation: Dutch Mormons in Twenty-first-century Europe

Alongside Utrecht’s largest canal, the nineteenth-century Neo-Gothic Martinuschurch dominates the centuries-old waterfront houses. Far be neath its glistening spire, the little entrance square, with a statue of the warrior saint Martinus at the center, bristles with people. Still, this is not Sunday; no service is held. This particular morning bears no difference from any other: just people going to their jobs. The splendid church has become a condominium; thirty-eight apartments fill the space created by this former house of worship. Residents at the top can boast large gothic windows, and middle floors have stained glass windows from floor to ceiling. The church’s exterior has been restored with great care during the transformation. Only at night is the change evident. Dutch custom calls for unshuttered windows, so light from the many apartments shines through the bay windows.

There is nothing unusual here, not in Holland. As in Germany, Switzerland, and other Western European countries, the houses of worship in Holland are being deserted. Non-ecclesiastical use is essential for the upkeep of more than half of the buildings.[1] The faithful no longer flock to the Sunday sermons of Dutch Reformed, Roman Catholic, or Neo-Calvinist (Gereformeerd) services. One indicator is the number of non-church-affiliated Dutch: 20 percent in 1958, 57 percent in 1991. Of church-affiliated Dutch, in 1966 51 percent went to church regularly (once a month), but in 1979 only 34 percent went. This percentage has decreased by about 1 percent per year down to an estimated 23 percent in 1991. In recent years the retreat has tapered off to about 2 percent every three years.[2] Differences by denomination are marked. Among Roman Catholics the retreat is most dramatic: from 85 percent in 1966 to 28 per cent in 1994. Neo-Calvinists show more stability: attendance dropped from 81 percent to 64 percent during the same years.[3]

In the 1970s and early 1980s the clergy tended to interpret this process as loss of the ecclesiastical fringe: People who had belonged only marginally to a denomination dropped out, leaving the hard core behind. This would provide the churches with a challenge to concentrate on their true calling to develop a community of faith. However, the process has not halted; the core is giving way as well, and the prognosis is that by about 2020 only the most devout—a small minority—will attend church.[4]

The average Dutch person has chosen not to belong to a denomination or to attend services. Compared to other countries in Europe, the Dutch situation is not unique. Though Holland is becoming one of the most secularized societies in Europe, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Ger many, and Switzerland are all comparable. The 16 percent of the total Dutch population that regularly attends church[5] is about the same as in West Germany and Great Britain. Norway has the lowest figure, with 5 percent attending church.[6]

Non-attendance is part of a larger phenomenon, secularization, which implies in its first phase a separation of secular and sacred institutions, and in its second phase the breakdown of religious institutions. Thus secularization is the dominant theme in assessing the future of religion.[7] For many observers, processes such as industrialization, urbanization, massive schooling, and the development of science have led to an erosion of the credibility of and need for religion. However, this view is too simple, picturing waves of enlightenment beating on the sands of unproven religion, washing superstition away with the advance of objective knowledge. Secularization is an observable but more complicated process, which we will see for the Dutch case in order to place Mormonism in the secularizing religious landscape there.

Secularization in Western Europe: The Crumbling of Pillars

Not long ago a Catholic comedian in Holland, for the amusement of his audience, recounted, “Last Sunday I watched our parish football team play against a team from a Protestant community. Objective sports admirer that I am, I applauded an action of the adversary. Immediately the man in front of me turned and chided: ‘Have you no faith?”‘ Such is but one expression of secularization in today’s Europe. Following David Martin’s incisive study[8] on the relation between church and politics, several types of secularization may be discerned: the type with a Roman Catholic monopoly (Belgium, France, Italy, Spain); the mixed type (Ger many, Holland, Switzerland); and the type with a non-Catholic state church (England, Scandinavia). Since my focus is on continental Western Europe, I will concentrate on the second type, of which the Dutch form a typical case.

The American situation is different from any of the European types. Martin characterizes the American situation as follows: a pluralist culture, federalist in politics and religion, with churches playing a large role in the interstices of society. Its low-status clergy has a constant turnover, according to the constant adaptation of religious styles to changing circumstances and to a floating population. The legitimation of the overall social order comes from a pervasive civil religion, with a definite social gospel: the welcome offered by the Statute of Liberty in fact is a symbol of general salvation, social inclusion, and universal civil rights. In America churches are denominations, competing in a market with other denominations, and judged by genuineness and performance.[9]

The most relevant type for Western Europe is Martin’s so-called mixed type, i.e., a large Catholic minority and a Protestant majority, a situation that has prevailed in several countries (Germany, Switzerland, and especially Holland), leading to a close intertwinement of religion with politics, education, health, and other institutions.[10] The process is one of subcultural segregation: around each denomination a political party, a school system, a broadcasting corporation, trade unions, medical and paramedical care, sports facilities and organizations, and cultural organizations have developed. A more or less complete subculture has been created for each denomination. This is a “pillar.”

Someone born in, say, a Neo-Calvinist Dutch family would be delivered in a Diakonessenhuis (a denominational hospital), with nurses from the same background. Nursery, basic schooling, secondary school, and university of the same affiliation are provided. During his school years a boy would not only attend his church but find his recreation in a Neo Calvinist football club, blow his trumpet in a denominational brass band, and enter a denominational student body organization at the denominational university. His wedding would take place in the church, career activities would be supervised by a Christian trade union, and ultimately his funeral would be taken care of by a “confessional” (the operative term in Holland) undertaker. A similar story could be told for a Roman Catholic citizen, and curiously enough even for a leftist non-believer, who has his or her own niche in a social-democratic pillar.

Not all denominations have been equally successful in creating their own pillars or subcultures. Neo-Calvinists and Catholics were among the first and most effective. Evangelicals came relatively late in Western Eu rope, but they too succeeded in creating their own socio-political and cultural pillars: political parties, a broadcasting corporation, and even an attempt at a university. However, they entered a shaky system, for the basic elements of, and public support for, such secularized pillars were al ready eroding.

Mormonism in Holland is too small to have its own pillar. Still, some Mormons have tried to create a pillar with a primary school, an old age home, shared time in public broadcasting, and their own periodical; but without success: the efforts were too few and too late. The tide for pillar building has passed. Also most Dutch LDS leaders have not been too happy with member initiatives, foreseeing practical problems and in principle opposed to segregation through pillars.

Politics in such a system was, and still is, a discourse of compromises; of give and take; of arguing and listening; of respect and tolerance, on the one hand; but steeled conviction, on the other. Politics and religion in these countries always have been characterized by moderation, absence of extremes, and middle-of-the-road theological pragmatism. Pillarization has been the dominant theme for about a century in Western Euro pean religion. However, for the last decade of this century and the first part of the next, de-pillarization will be crucial.

Dutch Catholicism offers the clearest example of the erosion of a pillar. Up until the 1960s the Dutch Catholic province, roughly the south of the country, was among the most orthodox, uniform, and obedient in the Roman Catholic church. The “pillar” it constructed between 1860 and 1960 has been its means towards “emancipation”; the Catholic minority at the turn of the century was less educated, had less power and influence, and was less vocal than its Protestant compatriots.

Within the span of two decades, however, Dutch Catholicism has, from the viewpoint of Rome, changed from a faithful servant to an obnoxiously progressive and extremely vocal church province. Vatican Council II initiated fierce controversies, great enthusiasm, and a general slackening of Catholic identity and practice. Discussions between parties in the debates, intellectuals versus administrative elites, could not be cur tailed by the clergy: “the bishops were forced to referee a civil war within the middle class, paralleling the civil wars elsewhere, e.g., England and the USA.”[11] The close, coherent, and efficient organization created for Catholic emancipation was now used for debates, discussion, and dis sent. “Previously, the system had echoed loudly to the tune of one message; now it resonated doubly with several conflicting messages, especially so given the progressive sympathies of media operators. Knowledge of being watched by the world acted as a further accelerator.”[12]

The reaction on the ideological level was clear. Mainline churches, like Dutch Catholicism, in the 1970s and 1980s became arenas of ferment over contemporary issues, political, cultural, humanitarian, and social. Third World projects abounded and still are crucial. Congregations were expected to adopt projects, either as part of ongoing programs or as partners with a project or Third World town. This might seem similar to the old link-with-the-missionary-in-the-field of Catholic congregations, but any resemblance is superficial. The missionary tie was a logical extension of the church; nowadays the project has become an alternative to the church: not a this-worldly translation of the message, but the message itself.

In the larger society churches have become focal points for discussions about moral issues. During the 1960s and 1970s there were mainly the issues of apartheid (South African apartheid was a particularly Dutch trauma), nuclear armament, abortion, homosexuality, divorce, unmarried cohabitation, chemical preservatives, etc. Here the same thing happened: the issue itself became central, replacing the transcendent message with a pragmatic and political one, even if the discourse was moral in nature.

For Mormons in Holland the absence of such discourse at their church was and is sometimes felt as a void; lessons and manuals hardly ever treat reality, focusing only on our desired perfection as members and families, avoiding the relevant issues of the times. The absence of Third World projects and the non-debate on moral discourse have meant political non-involvement, separating LDS members from their fellow Dutch.

Political debates have remained intensely moral in Holland, but with less and less religion behind them. Any moral controversy calls at the same time for religious, social, and political discourse. This loss of transcendency in the mainline churches has been applauded by several theologians as a return to the proper calling of the church. However, the issues themselves, like any moral dilemmas, have been tough, timely, but also time-bound. In 1996 the issues from the 1960s seem dated and are no longer topics of discourse. Most have disappeared because they have been generally accepted or resolved; nuclear armament and apartheid became obsolete through political change. The discussion on abortion is still with us, but given the degree of its acceptance by the general public and by most church-affiliated people, what remains are questions of detail: under what conditions, for what motives, etc. Euthanasia is the topic of the 1990s, having become an unofficially tolerated practice in clinically terminal situations and enjoying almost nationwide support.

The difference from the American scene is evident. In the U.S. denominations have entered a religious market situation competing in a religious arena defined by primordially transcendent claims. There are links with politics but not with any particular part of the political spectrum. The absence of a center in the American political dichotomy is important here. In Western Europe no direct competition exists among churches in the American way. Churches confront each other on non transcendent issues through pillarized institutions. They have eschewed the supernatural marketplace.

For European mainline churches, what remains is a pragmatic Christianity, a shared Christian cultural heritage. The issues are clearly this-worldly: human rights, environment, helping the hungry. Christianity in Western Europe finds its clearest expression in secularized institutions like the Red Cross, Amnesty International, Greenpeace, and other eco-movements. Generalized Christian notions of charity, partnership, stewardship, and mutual dependency form the guideposts of these organizations; they are the inheritors of general Christianity in Western Europe.

The Denominational Margin

The recent history of mainline Christianity in Western Europe might read as the demise of religion, but it is not. In fact it is a history of secularization, not only of society but of churches themselves. This redefinition of religious content simply brought the churches in line with their social and political environments. This kind of secularization, according to Stark and Bainbridge, “eventually leads to the collapse of religious organizations as their extreme worldliness—their weak and vague conceptions of the supernatural—leaves them without the means to satisfy even the universal dimensions of religious commitment.”[13] According to their theory, this kind of secularization is the standard way of reducing tension between the denomination and its social environment. As a consequence churches may flounder, but the supernatural does not disappear: “Only the gods can formulate a coherent plan for life.”[14] What is lost in the center grows anew in the margins. Indeed, in Western Europe religion is not on the way out; it is just changing faces.

Secularization has not occurred in the small orthodox sects, many of which split off in the last century from Neo-Calvinism. Neo-Calvinists themselves are less prone to secularization. Evangelicals and Neo-Calvinist splinter churches are doing well (in Holland it is even hard to count them, fission-prone as they are). Often they are tied to specific communities (like fishing villages or small agricultural towns), but also in large cities they have their place. Even their efforts at creating a new pillar in an age of depillarization are somewhat successful. Yet they represent not so much a new growth of religion as a resistant old core.

The truly new forms of religion are, of course, the most marginal: cults, sects, and movements coming from abroad, though a few are homegrown. The “non-respectable” fringe of the religious scene is doing well. Jehovah’s Witnesses, Adventists, Scientology, Hare Krishna, etc., are growing, though some have felt the general loss of interest in organized religion in recent years, and their growth in the past decade seems to be slowing.[15] Pentecostal movements are doing well, as are Evangelicals such as the Moravian Brethren.

Far more spectacular in Western Europe has been the success of East ern cults, movements, and currents, a large fringe with diverse forms of organization. The general context for the kind of speculative thinking in volved in these movements is exemplified in the increased acceptance of astrology. From 1966 to 1979 the number of people who “thought the stars might influence our lives” doubled in the Netherlands.[16] Led by the media, the “old sciences” of astrology, palm-reading, and the like re gained credibility and respectability. The New Age, with its amalgam of Eastern and Western occultisms, flourishes. This kind of margin has be come the fashion. Bookshops feature large and profitable sections of occult literature.

The more organized cults of Indian and Eastern origin are popular as well. The Rajneeshi Baghwan found, after Oregon, his firmest support in Holland, before the grand expose took place. The Unification Church, Hare Krishna, and others remain entrenched, though their heyday seems to be over. Some movements are homegrown, too. A number of European movements have sprung up with a mixture of Eastern and European con tents. Some remain small, but some have intense media appeal. Recently a healer cult, through one Yomanda, a former ballet performer, has attracted large numbers of people in Holland: train schedules have to be adapted to her performances. Though most people maintain a detached skepticism, interest in something new is common.

The rise of the occult goes hand in hand with a loss of confidence in Western science. Increasingly the limitations of technology for existential problems, as well as the inflated presumptions of science, are exposed: “Hinten der Kosten Explosion im Gesundheitswesen steht Verzweiflung fiber Endlichkeit” (“Behind the cost explosion in health issues stands despair over finality [when it will all end]”).[17] The demise of the supernatural has brought a heightened consciousness of the fragility of individual well being. The enormous growth of psychotherapies in the 1970s and 1980s is a case in point. Though the crest of this wave has passed, psychotherapy remains a continuous presence, in many cases fulfilling more than a few functions of religion.

Mormonism as Perpetually Marginal

Any religion is part of its environment. Though Mormonism in West ern Europe is an imported religion, Mormons still have to live in and with European culture. They are, in fact, products of that culture, so they will have to deal with the consequences of secularization. Clearly, general Western European culture is moving farther away from the basic elements of Mormonism. It is not separation between church and state that is a problem, for Mormonism has long accepted that idea and even made it into a social doctrine. However, the process of secularization of churches in Holland, and in other European countries, implies the dissolution of religious institutions. The trend is towards non-organized religion or networking religion. Secularization in Europe involves de institutionalization. The idea that salvation is found in a specific organization, led by a well organized hierarchy with an authoritative voice, will become more alien to European culture. Notions of hierarchy, authority, and power are increasingly suspect. In Europe the time of the theocracies is over. Thinking in absolutes, in fixed norms and standardized value systems, becomes increasingly marginal culturally. Transcendental theology with a closed theology and half-open scripture is out of step, both with the secularizing majority and with the immanence-oriented theological margin.

So tension between European Mormons and the cultural environment will increase. In a few areas Dutch and other European members have to accommodate the general society. For instance, in Holland tolerance of alternative forms of marriage relations (such as common-law marriages which have been accepted legally and socially); of alternatives to the traditional nuclear family; and especially of alternative forms of sexuality, are all points of difference. Condemnation of homosexuality is seen as intolerance (a damaging epithet); recent findings of genetic origins for homosexuality have received a wide and receptive hearing in Western Europe. Mormonism’s condemnation of homosexuality means reduced respectability in Europe.

As they grow more distant from the cultural center, European Mor mons will increasingly find themselves at the ecclesiastical margin. Ironically enough, this is the very position society has allotted Mormons in the past, and against which European Mormons have battled since World War II, striving for respectability and legal acknowledgement (the latter finally acquired). However, in the course of Western European secularization this margin itself is of rising importance and respectability and does hold some opportunities for future development and growth. The question then becomes, if the center moves away, how well will Mormonism fit into the margin?

Mormonism shares a number of features with Evangelicals: the orthodoxy, the link between creed and behavior, obedience to authority, some emphasis on the experiential side of religiousness, and inner directedness. Some social characteristics are also comparable: small, homogeneous congregations, mutual self-help, intense internal networking, a sharp distinction between in- and outgroup. Ironically, from a political point of view, Evangelicals are ill at ease with Mormons, branding them members of a heretical sect mainly because of the extra scriptures. Yet a number of Mormons feel at home in the Evangelical “pillar”; for ex ample, in their broadcasting corporation. Orthodox Neo-Calvinists are also part of this margin; they, however, being chips off the old Calvinist block, enjoy greater respectability in Dutch society. Even when their practices clash with the common good, authorities and the general public are tolerant. For instance, several Calvinist groups prohibit inoculation; thus, every odd decade a small polio epidemic scourges their communities, also endangering other people. Yet the government has never made polio vaccination mandatory, though the press and the general public have been critical. Mormonism does not enjoy that type of public tolerance.

This part of the margin, however, is not the most productive one. The occult religious milieu is far more dynamic in terms of its following, though it is often difficult to speak of membership. However, Mormon ism is almost diametrically the opposite of these movements, with their diffuse doctrines, absent authorities, non-organization, and individual salvation. The fuzzy organization and identity of these movements stand in contrast with the clear-cut organization and unambiguous boundaries of Mormonism. Finally, the low level of commitment in these cults, the amount of shopping around, and ecclesiastical eclecticism are not encouraged in Mormonism. So even in the margin Mormonism occupies a position among small stable denominations lacking spectacular growth, but it is never accepted as one of them.

Most European LDS members have become used to this position.[18] In most countries social ostracism is not severe. Holland, for example, does not always live up to its reputation of tolerance, and in indirect ways LDS members have been put at some disadvantage in the job market and especially in public positions. Yet the trend in society is toward less per sonal judgments, toward more latitude for alternative lifestyles, even for Mormons. Anti-Mormon drives are not likely in Western Europe; any clergy willing to instigate them would lose respect.

Dynamics in Western European Mormonism: Ethnization with Accomodation

The Impact of Immigration

Many changes are affecting Europe. One is immigration in recent de cades, requiring the accommodation of an increasing range of cultures. The depillarization process, as well as the specific forms of secularization, affect only the main population; and the traditional mono-ethnic situation is breaking down in many countries. Not only does this engender the rebirth of ethnicity, currently the scourge of eastern and southeastern Europe, but also the arrival of other religions, such as Islam. A consider able ethnic fringe is developing in Western Europe, with immigrants of ten depending on state welfare. This ethnic lower class offers a suitable terrain for missionizing, especially the recently arrived Africans and the more entrenched Surinamese and Antillians in the Netherlands. They occupy a position in society similar to that which the LDS church occupies in the ecclesiastical environment. Their receptivity to the missionaries’ message is greater than that of the mainstream population. So the growing ethnic margin of European societies might fill the religious void cre ated by a secularized middle class.

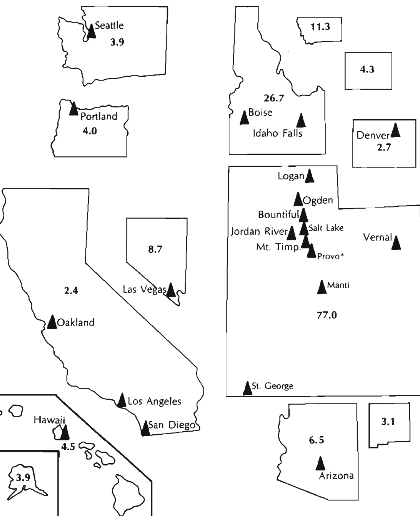

In the Dutch Mission (including Dutch-speaking Belgium, most of the time) during the past fifteen years (1980-94) a total of 1,960 baptisms have taken place, averaging 131 per year, with about one-third coming from member referrals and two-thirds from missionary contacts. In the early 1980s mission presidents were hesitant to baptize ethnic minorities, fearing an “easy come, easy go” attitude in these converts. In the late 1980s pressure to proselyte among these groups increased, and so did baptisms. Of the 110 baptisms in 1994, sixty-six were from missionary contacts and included the baptisms of twenty-eight ethnic converts; forty four were from member referrals and included four ethnic converts.[19]

No longer will middle- or lower-class Dutch nationals, who used to form the bulk of converts, continue to fill the ranks of the church. The distance between their culture and the Mormon subculture is growing larger, making the transition harder and missionaries less successful. For people at ease with Dutch culture, and with the trends in that culture, the step into Mormonism demands an increasing reorganization of values and a rethinking of norms. Though occupational and societal consequences of their LDS membership will be less serious, the cognitive trans formations will be greater. However, the immigrant population presents a different situation. At least the non-Muslim among them have a definite need for attachment, for reassurance, for inclusion in a closed community. Their view of hierarchical authority, as well as their value systems, is much closer to LDS ways. In their countries of origin secularization is only just starting, and religion remains a meaningful institution.

Increasing proportions of immigrants and refugees are thus joining the church. The opening of eastern Europe will enhance this tendency. The present experience is that immigrant converts come in quickly and fade away gradually. They tend to be “consumers” of new religions, without taking part in leadership positions or activities. Several reasons account for this: They lack standing in Dutch society, have language problems, and come from cultural backgrounds where religion has always been more consumed than produced. Baptism often has some opportunism to it: they shop around. In many of their background cultures (especially the African ones), plurality of religions is an accepted way of life, a strategy for survival and optimization of life-chances; the pattern is repeated in Holland. However, Mormonism does not make this strategy easy, so they fade away once the heyday of attention is over.

The Shrinking Core of Long-term Members

Branch and ward leadership positions still have to be filled by nonimmigrant members. As the balance of convert baptisms continues to shift towards immigrants, the majority of Dutch will be second-, third-, and fourth-generation members. They will run the wards, serving an increasing fringe of ethnic Europeans, who, in turn, will be only marginally involved in activities and leadership. A small core, with slowly changing personnel, will work hard on behalf of an increasingly floating population, which shops around for religious alternatives. The rotation of callings in such a system implies a recycling of relatively few leaders through the positions, often to return to the same position two or three times. Someone who becomes branch president or bishop for a third time will not be exceptional. This trend will endure as the number of potential leaders remains limited, even among second-generation Mormons.

Given an organizational struggle to retain long-term members, and the growing shortage of non-immigrant Dutch converts, the future will bring a trend already evident: the “ethnization of Mormons.” Ethnization is the process by which a group exaggerates its differences with the main population in a situation where they increasingly interact, and in which its culture in reality grows less distinctive. I expect this to happen to Mor mons for several reasons. Being a Mormon in twenty-first-century Eu rope constitutes an effort, not a comfortable identity. The self-definition of Mormons will not coincide with the place they occupy on the fringe. Lacking public respectability as Mormons, they will not simply accept their Schicksalsgeworfenen (the fate to which they have been thrown). Most long-term members will develop a dualistic attitude. On the one hand, they will define themselves as Mormons, active, obedient, and worthy; in the branches and wards they will share in an internal discourse of feeling privileged to be Mormon.

On the other hand, they will tend to downplay their membership in public life, among gentile peers, colleagues, or neighbors. Though tolerance in Holland is great enough to warrant a group’s right of existence, individual relations are too brittle to expose to contrasting definitions. Members will be comfortable in the church among fellow members, but also reasonably comfortable in the secularized tolerance of the general society, as long as they do not mix the two spheres. Living a dual cognitive life inevitably draws the minority towards the general culture of the majority: Mormons will become more similar to their cultural environment, while continuing to stress their differences. The fact of being a second- or later-generation Mormon enhances this process; members without a first hand experience of living in another denomination will tend to overdefine the gap between them and others. Stereotyping the other is an integral part of ethnization. This ethnization process enables members to manipulate their various identities, either defining their Mormonism as different or being part and parcel of European culture and society. European members thus will follow to a considerable degree the developments and tendencies of their own cultures, while defining themselves as different at the same time. A relatively high degree of societal tolerance for their peculiarities will permit them to define their own identity in a secular society.

Relationships with Non-member Friends and Relatives

The bifurcated attitude resulting from ethnization appears especially in missionary work. No topic is treated as often in conferences, priest hood meetings, or sacrament talks; yet no topic is as tedious to the average audience. Members in Europe must live in two worlds: a secularized one with high tolerance but increasingly alien to fundamentalist preach ing, and the church environment which resists secularization. Some degree of disjuncture in the action and thinking of LDS members is essential for successful living; yet the call to proselyte is precisely the intrusion of one of these domains into the other. In Western European culture this kind of intrusion is resented. In Europe people tend not to mix socially with shop or office colleagues but have separate friends, neighbors, and acquaintances for hobbies and sports. So missionary work is something of an oddity in secularized Western Europe, both because it is active preaching and because of the fundamentalist content of the message.

One other issue, relevant for most European members, is their relationships with non-member relatives. In recent decades becoming a member has not necessarily entailed the rupture of relations with one’s family, at least in the Netherlands. Yet all members still have to define their church ties within the circle of their own personal families. Manuals written in Utah offer no help here, especially in the case of wayward children, a common phenomenon. The need for continuing relationships with non-member children and non-member spouses runs counter to the definition of self versus other in Mormonism. Again church manuals of fer no guidance. European members feel a need for realistic treatment of everyday problems. In these family matters separation between church and public spheres no longer is possible, a predicament exacerbated by divorce. Since primary relations tend to be modelled more after European ways than Mormon ways, the growing divorce rate in European societies will reflect itself in a growing divorce rate among Mormons, as well. Frowning on this development from the pulpit will have no effect. Divorces represent the fastest growing part of the church population, but officially they do not exist in the church. No attention at all is given to their problems; no programs to retain them in the fold; no discussions about how ex-partners should interact; for in small European branches and wards ex-partners constantly have to interact at church. Stake conferences increasingly are becoming occasions for ex-partners to meet (or avoid) each other. For Dutch members it is incomprehensible that the church does not address these practical problems. In the matter of ruptured primary relations the continuing pain and problems are issues which should be addressed.

Doctrinal Homogeneity and Ethnization

The ethnization process has accompanied a general church change in the doctrine of gathering. “Gathering to Zion,” up to the last decade still common among European Mormons, is losing its appeal and will fade away. Millennial movements, too, inside or outside of Mormondom, will continue to be marginal in Europe. In the church it is possible that some muted hope of gathering to the U.S.A. might surface again briefly with the approach of the new millennium, but it will quickly subside. Some appeal of America will always remain, not as a millennial attraction, but as an attraction to a church stronghold, or even to BYU. Loss of the “Zion-America Mystique,” however, is inevitable. Even the appeal of the missionary has changed. Not only do European girls no longer marry American missionaries in any numbers; missionaries are no longer seen as “representative of the church” or even “representative of America.” Increasingly they are seen as youngsters in “uniform” in need of guidance.

Important in this respect is the changed attitude towards America it self, and of course Mormonism still has strong American overtones. The position of the United States in European culture has been ambivalent. After the pro- and anti-American decades of the past, the general political and cultural image of America seems to have stabilized. The times of the “baseball baptisms” are over, never to be repeated, not only because of more recent church policy, but also because the image of America is not as alluring as it used to be. In European youth culture, and in the subculture of the business world, the influence of the U.S.A. is large and pervasive, but in other subcultures this is less the case. The standard political term Amerikaanse toestanden (American conditions) in the Netherlands has negative overtones. The image conjured is one of a sharp division be tween haves and have-nots, low social security, high rates of violence and crime, and an internal arms race due to a terrible gun craziness (Euro pean Mormons wonder why the church does not speak out against private arsenals).

The absence of internal variety in European Mormonism facilitates the drawing of sharp boundaries between “them and us,” an essential feature of ethnization. In doctrine and practice “middle-of-the-road” Mormons tend to dominate. The absence of polygamy fundamentalists, Christian Identity adherents, or other Mormon splinter groups leaves quite a monolithic Mormonism. The smaller sizes of wards and branches promote doctrinal and behavioral conformity as well. Dutch-speaking LDS on record in 1994 numbered 7,734, with an average attendance at sacrament in the first quarter of 2,885, or 37 percent. These members are distributed among forty units, more often branches than wards.[20] One specific ward, about average, has 162 members of record, with a sacrament meeting attendance of sixty-five: fourteen in the Melchizedek priesthood, six in the Aaronic priesthood, twenty-one in Relief Society, six Young Women, and eighteen in Primary. The truly active members comprise eleven families with young children; two young married couples without children; five couples with adult children; seven women with children (six of them divorced, one remarried to a non-member after divorce); one divorced man with children; eight single women (two of whom have been divorced though one now has a non-LDS husband); and six single men (two of whom are divorced). Of the twelve divorces, in one case both ex-partners have stayed on in the same ward. Of the eleven full-member families with children, nine are second-generation LDS, in three cases with their parents living in the ward (counted as older couples).[21]

Almost all older couples have one or more, sometimes all, of their children inactive or disaffiliated. In Europe people are either members and more-or-less active, or they are totally inactive. Europe has few “Jack-Mormons” on either side of the boundary; most wards and branches have no marginal members in a practical sense. Dissenters do not stay in the church, for moving out is easier than staying. Once having lost contact with wards and branches, people seldom return. Whereas in the U.S.A. a high disengagement rate is accompanied by a substantial return rate,[22] the Dutch LDS scene has almost no returnees. One reason is that in Holland raising a family does not typically call for church affiliation. Thus youth who drop out seldom return. Such might be even more true for the elderly. Their activity, where mobility is required, becomes problematic at a time when they are gradually losing self-sufficiency. They tend to gravitate for care to institutions in one of the “pillars” (identified with mainline Christian churches), where they gradually fade from view.

Ethnization is the drawing of boundaries in situations of relative similarity. West European Mormons will do so on a doctrinal basis, while still conforming to the general culture. Another distinction appears in education. American Mormons can boast a somewhat higher education level than the American average; not so in Europe where members seem to have lower general levels of education than non-members. The over representation of Mormon converts in lower clerical jobs (as in other proselyting churches) has led to an internal Mormon culture where education has a slightly lower value than in the rest of society. A latent anti-intellectualism pervades much of internal Mormon discourse. Spirituality counts more than intellect or learning. At the same time, somewhat ironically, European culture holds academics in high esteem, higher than in the U.S.A. Almost all public opinion ratings have the university professor at the top as the most respected status in society (though not the highest paid!). Here the Mormon culture in Europe has been at variance with the general cultural environment. However, this difference seems to decline quickly in the next generation, where higher education becomes more important. In this respect perhaps the situation is not so different from that in the U.S.

One example of such a second generation can be found in the participants of a typical Young Adults camp. Of the seventy-two Dutch participants in last year’s camp, a third had an education on the LBO level (lower professional education) and a fourth on MBO level (medium professional level), leaving slightly under one-half with higher education (10 percent with university education and 30 percent with higher professional schooling). Of those seventy-two participants, fourteen are converts and fifty-eight are second-generation Mormon youth. Of the latter, fourteen had completed missions. After four years thirty-one had married in the church and four others with non-members. The educational distribution of this “sample” is comparable with that of general Dutch youth population. There is, however, a tendency among Mormon youth to opt for “practical” or applied sciences and skills—like nursing or technical training—rather than purely intellectual ones. A Mormon youth opting for, say, psychology is viewed with some alarm. Medical professions are in high favor.[23]

So the second generation catches up, despite the lingering anti-intellectualism, and despite the pressure of leadership positions in the church, confirming Niebuhr’s thesis that in any new religious movement after a few generations the level of schooling rises.[24] Whether traditional LDS emphasis on education will result in an improved Mormon profile in higher education remains to be seen. One problem is that the university system in Europe differs importantly from its American counterpart. Most of the medium professional or vocational training in Europe is done in separate schools, not in universities. European universities generally do not have a level comparable to the bachelor’s degree, which allows great numbers of American youth a respectable way out of the university system, after a thorough but short brush with higher education. Most vocations and professions in Europe have their specific schools, and universities tend to concentrate on more academic subjects, up to the M.A. or M.S. as the first graduation level.

For Mormon youth in Europe this implies that, given their practical orientation, they tend to seek schooling in specialized higher vocational schools. This fact, and the structure of universities, makes a mission more of a problem than it is in the U.S.A., since a two-year leave of absence can be very disruptive. The only feasible point at which to interrupt one’s education is after secondary schooling; but for those not in college this comes too early. So the missionary call is out of sync with the educational system, which creates difficulties for Mormon youth. On the whole the church has little influence on schooling plans, so the Mormon community will come increasingly to reflect surrounding European trends.

The situation might be different for women, as Mormon women in Europe (like other women there) tend to favor home-making and child rearing roles. Holland especially has the lowest proportion of married women working for wages (31 percent). In other countries of Europe the figure is higher, with Scandinavian countries at the top (where two-thirds of married women work outside the home). The traditional housewife is very much present, and of course her role is reinforced by church values. In lower levels of secondary education Mormon girls are overrepresented. The few of them who do opt for advanced education still expect to give priority as soon as possible to child-rearing and home making over career or profession.

Ethnization is further enhanced by the strong endogamy in the Mormon peer group. For example, in the above-mentioned Young Adults group the majority married within the group. For Mormons this is nothing new, but in Western Europe peer groups are limited and partner selection is restricted. The LDS penchant for endogamy can be seen more clearly in the case of that Dutch-speaking ward mentioned several para graphs earlier. In this ward were two LDS mothers (A and B), both of whom had married non-LDS men (though one subsequently divorced). The children of Mother A married those of Mother B. Their children (the grandchildren), in turn, intermarried with those of a third (divorced) LDS woman, Mother C. The principals and offspring of those unions comprised a third of all active ward members. In the literature of anthropology one would have to look far to find a similarly dense endogamous network.

Most LDS youth find marriage partners in different wards, however. European cross-national marriages, though on the rise, are still a minority. In the future this type of internationalization might increase, though the centripetal tendencies of the various language communities preclude a large increase. In those cases where the partner comes from beyond the Mormon-gentile boundary, recent years have shown a hopeful sign. In earlier years mixed marriages tended to imply either restricted activity for the member-spouse or a gradual drifting away; with the second generation increasingly the non-member partner is drawn into the church, though the numbers are still too small to predict reliable trends.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In general, European Mormons will have to struggle against growing alienation from the values of their own LDS culture while growing to resemble more the social profile of the average Dutch, German, or Belgian. The tensions thus created can be both a challenge and a problem, resulting probably in a stronger definition of “otherness” even in situations of great similarity. Cognitive retrenchment, the redrawing of the borders of orthodoxy, is not likely to happen. Tolerance in European culture, and the relative comfort Mormons enjoy there, will preclude a siege mentality. So in order to live in reasonable comfort (an important European value) in his or her society, the European Mormon will have to invest considerable mental effort to bridge the gap (on the one hand) between Mormon culture and mainstream culture, between his or her view of society and society’s view of itself and of him- or herself, and (on the other hand) be tween the expectations of the Utah church and the reality of Mormonism in Europe. At least in Holland, and in most Western European countries, the larger society is tolerant enough to make room for such cognitive maneuvers. Persecution, harassment, and problems with authorities will di minish, mainly because of a lack of concern.

We can expect internal changes in the European church in the next century mainly from changing attitudes among second- and third-generation local leadership. They will be better educated and will probably al low more leeway for diversity. Their room for maneuver, however, will depend on the room allotted them from higher up. The growth of the European church will be mainly internal, with strengthening leadership pat terns and a local Mormon scene with its own ideas. One important factor will be the autonomy the Area Presidency gives to local leaders and receives from church headquarters. A more European and more permanent Area Presidency, with more authority of its own, might reduce some of the control and provide some flexibility for local leaders. However, the present trend seems to be the other way, towards uniformity and control from the center, which will only aggravate the problems.

Flexibility is important for several issues in particular. One is the mission. Mission terms (age, duration) have to be flexible to fit the European educational structure. In Holland, for example, boys leave secondary school at about age eighteen, and a mission is best served before entering the university. More flexibility in mission duration, say, eighteen months, would also alleviate some strain. A second and related issue is the need to encourage high aspirations among youth and to promote education. Latent millennialism, mission calls at inopportune times, and the huge load of leadership in small units all form obstacles to educational and professional development.

Marriage and divorce form a third issue. As elsewhere divorce rates are mounting, and Dutch Mormons, at least, increasingly resemble their fellow countrymen (roughly 40 percent of first marriages end in divorce, with half that for second marriages) in this regard. In the coming decades divorce will be the main internal threat to Mormondom. The present church stance implies a definition of divorce as failure, and divorces seem a nonexistent category in the church. An already traumatic situation is thus exacerbated by the church. What is needed is some rethinking about our teachings on the family institution to accommodate non-ideal family arrangements. More broadly, the standardized “script” of an individual’s life in terms of mileposts (mission, temple marriage, children) could be reconsidered.

Whatever the internal dynamics, the main interaction of Mormons will always be with their larger cultures. Living implies facing moral di lemmas. For European Mormons the church needs to encourage more discussion of existential dilemmas, of how to live productively with inactive children, with non-member partners, with ex-partners. Decentralizing the production of church manuals would make this easier. Yet for European Mormons the issues do not stop with their own family circles. Political and general moral issues are of great concern, including poverty, economic development, political dilemmas, and the like. For Europeans the Utah church seems overly-focused on sex-related problems, ignoring problems of violence, pollution, and poverty. Though possibly far fetched, one European LDS style might be the development of a “green Mormonism.” Ecological issues weigh heavily in Europe, and European members sometimes wonder why church leaders say so little about eco logical problems. Mormon doctrine easily can accommodate an involved partnership with the environment, offering another venue for coping with the chasm between doctrinal definitions and societal realities.[25] This raises again the issue of the general inward-orientation of the church. For European members more activities and projects aimed at alleviating poverty and at development more generally in the world would greatly enhance their sense of LDS pride and alleviate some of the strain in trying to be both Mormon and European.

[1] A. Stinissen, Functieverandering van Kerkgebouwen (Change of Function in Church Buildings) (RUG: Groningen, 1989), 56.

[2] J. W. Becker and R. Vink, Secularisatie in Nederland, 1966-1991 (Secularization in the Netherlands, 1966-1991) (Rijswijk: Sociaal-Cultureel Planburea, 1994), 116.

[3] Ibid., 51.

[4] Ibid., 190.

[5] The self-report basis of these studies might even make for some exaggerations. Such church attendance records as do exist (also unreliable) give much lower figures.

[6] The same holds for the 8 percent of the Dutch who cling to a literal interpretation of the Bible; this figure matches those of most Western European countries and of the Eastern European as well (Becker and Vink, 168).

[7] R. Stark and W. S. Bainbridge, The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival and Cult Formation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 429.

[8] D. Martin, A General Theory of Secularization (Oxford, Eng.: Blackwell, 1978).

[9] Ibid., 25-32.

[10] G. Schmidtchen, Ethik und Protest. Moralbilder und Wertkonfliktejunger Menschen (Op laden: Leske & Budrich, 1993); M. A. Thung, Exploring the New Religious Consciousness (Am sterdam: Free University Press, 1985).

[11] Martin, 192.

[12] Ibid., 193.

[13] Stark and Bainbridge, 429.

[14] Ibid., 431.

[15] Jehovah’s Witnesses, for instance, experienced a decrease in adherents in 1994, for the first time in decades (R. Singelenberg, personal communication).

[16] From 21 percent to 40 percent (W. Goddijn, H. Smets, and G. van Tillo, Opnieuw: God in Nederland [God in the Netherlands, Again] [Amsterdam: De Tijd, 1979], 123).

[17] Cited in ibid., 151,231n6.

[18] The difference with Belgium, where ostracisim is very present, is striking, though. See Wilfred Decco’s essay in this issue.

[19] Monthly baptismal reports of Netherlands Mission; notes in my possession.

[20] Correlated reports from the three Dutch stakes (Apeldoorn, Utrecht, and Amster dam) and from Flanders; notes in my possession.

[21] These data come from a very knowledgeable source.

[22] S. L. Albrecht, M. Cornwall, and P. H. Cunningham, “Religious Leave-taking: Dis engagement and Disaffiliation among Mormons,” in D. G. Bromley, ed., Falling from the Faith: Causes and Consequences of Religious Apostasy (Beverley Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1988), 62- 80; H. M. Bahr and S. L. Albrecht, “Strangers Once More: Patterns of Disaffiliation from Mor monism,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28 (1989): 180-200.

[23] Records of young adult camps in the Netherlands and additional oral information of several participants; notes in my possession.

[24] Stark and Bainbridge, 99,100.

[25] See, for example, Larry L. St. Clair and Clayton C. Newberry, “Consecration, Stewardship, and Accountability: Remedy for a Dying Planet,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 28 (Summer 1995): 93-99.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue