Articles/Essays – Volume 11, No. 2

Everything that Glitters | Ron Carlson, Betrayed by F. Scott Fitzgerald

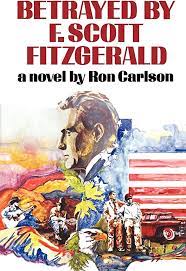

Though set in Salt Lake City, Betrayed by F. Scott Fitzgerald is not a “Mormon novel”, even in the way that Scowcroft’s The Ordeal of Dudley Dean is—which does not mean it will not interest Mormons. Still, the first thing to interest them will not be Carlson’s Salt Lake City, nor the drunken academic party that opens the book—at least not in the way it seems to have misled Francine Du Plessix Gray into calling it “a nervy, very witty romp through contemporary Academe” (as quoted on the jacket). Most Mormon readers will be first interested in the character of Larry Boosinger and his language, because they, and not plot nor place, hold this book together.

Character is perhaps too precise a word. It implies a clear (or critically clarified) psychological profile of a figure in a narrative. Boosinger is defined not through his psyche but through his gestures. It would take a critic, not a reviewer, to clarify any character he might have. On the other hand, Larry Boosinger is a “character” familiar in modern fiction—all gesture, with the flamboyance of the innocent romantic, the student prince, monarch of himself: he is living in late adolescence, an American prolonged adolescence. He shows no ties to his family but memory and love, no responsibilities but those of a teaching assistant (and those primarily selfish), no obligations but to pay the rent (and other bills).

That is not entirely true. Larry has a fiancee, Lenore, who is leaving, whom he wants to stay, and a friend with whom he shares an apartment, Eldon RobinsonDuff. Both he and Larry are writers, and it is one of Carlson’s gestures in defining his book to have these two supply him with epigraphs: “Everything that glitters should be gold” from Eldon, and

My undergraduate days, having left my bed and board, I can no longer be responsible for their debts.

Larry Boosinger, Daily Utah Chronicle

Boosinger’s epigram not only defines his “character” but illustrates, in the attribution, Carlson’s manner of generalizing from the specific, here using the name of a student newspaper (at the U) as a claim for the book. But is it a daily Utah chronicle? Some Mormon readers will find themselves asking that question for the Utah in this novel does not match, say, that of Don Marshall or Doug Thayer. Comparison with other writers is not really fair, for this is largely a (Salt Lake) city novel, but Carlson’s Salt Lake does not develop like one of the new instant dry photographs, over time, in one’s hand. It may simply be unfamiliar territory to LDS readers like me. But it remains for me the topos of the action, an abstract place never localized. Carlson likely knows exactly where are the houses, apartments, trailers and stores of which he writes, but it is not one of his concerns to tell those who do not know.

This generalizing of place helps mark the book as more romance than novel, matching the emphasis on “character” and gesture that replaces plot. True, there is a narrative line: Larry wins at drunken croquet and offends his teachers and fellow students; Larry and Eldon show a movie in their apartment and offend their landlady and the police; Larry drops out of school to write, offends himself, has an auto wreck and offends the garage owner who fixes his truck, who then uses it to commit a crime which lands Larry in prison at the Point of the Mountain; Larry escapes and offends no one—is in fact ignored by police; Larry and Eldon go fishing to rest from offense; Larry enters a demolition derby staged by the garage owner and offends him and his henchmen with a spectacular crash—which batters him out of adolescence and into adulthood, and whereby he “clears his name”; Larry settles into convalescence with Eldon’s widowed sister Evelyn, and family life begins to heal the wounds of self-conscious romanticism that adolescence has inflicted upon him.

Having mentioned that Carlson’s language glitters (in keeping with Eldon’s maxim), let me quote Larry quoting Eldon: “His motto was simply, ‘If you want to read a good book, you have to write it’.” That concept, along with the following observation from Larry, governs his structuring of the book and frees Carlson from the necessity of a conventional plot: “Writers’ block (which troubles Larry at the time) is not really so much massive cerebral shutdown, as it is a toxic belief in all the bad things people have ever said about you”. Larry writes his book as an aftermath to the crash which breaks him of adolescence, and likewise smashes his writers’ block. The detoxifying wit glitters on the page. But the gold of the book is its record of Larry’s escape from the self-derived romantic lunacy (which he credits to his worship of F. Scott Fitzgerald – hence the title) he has lived, a madness originating in what he calls “easy access … a source for a major portion of all the grief and regret that blindingly swarm this planet”. In his break-out from habits of easy excess, Larry reveals the sentiment with which Carlson hooks the reader.

The fishing scene celebrates rural, earth-grown values—wisdom, patience, careful work. Much of the wisdom (in scene and in book) comes from Larry’s father, memories of whom surface like a mythic trout, one Larry is trying to hook. His father’s maxim, “Blame is not important. Whose fault it is will not get anything fixed”, introduces the book and provides the easy-going tone, devoid of much rancor, in which Larry narrates. And the close, which finds Larry enjoying a present domestic bliss and projecting it into coming days, living a settled life with Eldon’s sister Evelyn and her son Zeke, is the fitting development of such solid values.

The sentiments, the concepts controlling the action, tone and outlook of the narrative, will interest a Mormon reader of the book, not the place, nor any possible gossip about its people, nor observations on its things. This is where the value of the book resides, for although its considerable charm will delight the readers, only its truth to those sentiments will bring them through.

Betrayed by F. Scott Fitzgerald by Ron Carlson. New York: Norton, 1977. $7.95

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue