Articles/Essays – Volume 22, No. 2

Fawn Brodie and Her Quest for Independence

Fawn McKay Brodie is known in Mormon circles primarily for her controversial 1945 biography of Joseph Smith—No Man Knows My History. Because of this work she was excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In the 23 May 1946 summons, William H. Reeder, president of the New England Mission, charged her with apostasy:

You assert matters as truths which deny the divine origin of the Book of Mormon, the restoration of the Priesthood and of Christ’s Church through the instrumentality of the Prophet Joseph Smith, contrary to the beliefs, doctrines, and teachings of the Church.

This reaction did not surprise the author of the biography. For Brodie had approached the Mormon prophet from a “naturalistic perspective”—that is, she saw him as having primarily non-religious motives. As she later noted: “I was convinced before I ever began writing that Joseph Smith was not a true Prophet” (1975, 10). Writing No Man Knows My History was Brodie’s declaration of independence from Mormonism. In the words of Richard S. Van Wagoner, Brodie’s “compulsion to rid herself of the hooks that Mor monism had embedded in her soul centered on her defrocking Joseph Smith” (1982, 32). She herself, in a 4 November 1959 letter to her uncle, Dean Brim hall, described the writing of the biography as “a desperate effort to come to terms with my childhood.”

Fawn McKay Brodie came from patrician Mormon stock.[1] Her paternal grandfather, David McKay, helped found Huntsville, the small Utah farming community ten miles east of Ogden where she grew up. Her father, Thomas E. McKay, was a respected Church leader who served as president of the Swiss-German Mission and later as president of the Ogden Stake for nineteen years. Politically active, he had been president of the Utah Senate and later state public utilities commissioner. His older brother and hence Fawn’s uncle, David O. McKay, was already a member of the Quorum of the Twelve when Fawn was born. On her mother’s side, Fawn’s grandfather, George H. Brimhall, served as president of Brigham Young University from 1904 to 1921. Her mother, Fawn Brimhall (for whom she was named), was an accomplished water-colorist of minor renown.

Fawn, the second of five children, early demonstrated her exceptional intellectual abilities. Her older sister Flora recalled:

When I was five and Fawn three, I remember mother trying to teach me to repeat the poem “Little Orphan Annie.” I was struggling just to learn the first verse. One morning [when] mother and dad were in bed and we were playing at the foot of the bed . . . mother asked me to say the poem. I just barely got past the first verse and stopped. Fawn piped up, “Let me say it mother,” and she went through all three verses without one mistake (Crawford n.d.).

When Flora was six and due to begin first grade, an epidemic of whooping cough persuaded the McKays to teach her at home rather than send her to school. Her mother taught her to read, write, and do simple arithmetic. Four year-old Fawn was eager to learn along with her older sister, and by the following spring, she was reading fourth grade books. When she was formally enrolled in school two years later at age six, she was initially placed in the third grade because she was already reading at a sixth grade level. Convinced of her exceptional ability, the principal gave Fawn an IQ test and found that “she went over the top score” (Crawford 1988). He then promoted the bright six year-old to the fourth grade.

In a schoolwide spelling bee held during that fourth grade year, Fawn defeated everyone in grades four through six except for one sixth grader, a bright twelve-year-old, twice her age. She wrote poetry, and when she was nine Child Life, a national literary magazine for children, published one of her poems. She later recalled that it was “an unspeakable thrill to see my name in print. I had fantasies about writing great short stories and fine novels [but] did nothing about it” at the time (Berges 1977).[2]

Fawn’s precocity, however, was not without its price. Because she was three to four years younger than her classmates, she was “quite insecure” and reticent (P. Brodie 1988; McKay 1987). Her sister Flora (who was in the same grade) was much more at ease.

Fawn attended school dances, which were generally stag affairs. One former classmate, Louis A. Gladwell, recalled that Fawn, despite being skinny, tall (she ultimately reached 5’10”), and “kind of gawky,” glided across the dance floor gracefully. Her personality was sunny and upbeat, and Gladwell recalled her declaration that “she intended to enjoy life to its fullest, to hear the lovely music, read the great books, and enjoy the hills and dells of Huntsville” (1981; 1988). Although only thirteen, by the end of her sophomore year, Fawn was dating, on a steady basis, Dilworth Jensen who, according to Dilworth’s daughter Patricia, was also from Huntsville and five years older (P. Jensen 1988). Fawn herself described Dilworth as “tender, sweet, witty, [and] gallant,” noting in her later recollections that she “fell passionately in love” with him (F. Brodie 1980). But theirs was a stimulating intellectual relationship as well. Barbara, Fawn’s younger sister, recalled that when they would attend a dance, “they would generally just stand in one spot .. . so absorbed with conversation that many times they weren’t aware when the music stopped” (Smith 1982, 11). Fawn and Dilworth frequently double dated with her older sister Flora, who was seeing Dilworth’s older brother Leslie.

Fawn attempted to overcome her shyness by participating in school activities, student government, and especially debate. A vivid storyteller, she spoke frequently in student assemblies, won two state-wide oratorical contests, and was a member of the Weber debate team that took the state championship. An excellent student, she was salutatorian for the Weber High class of 1930. She was fourteen.

Besides the difficulties of trying to fit in socially with older classmates, Fawn was aware that her parents did not have the same approach to their Mormon beliefs. She described her father as “very devout” and felt that through his quiet assertiveness “he was always pulling me, trying to pull me back into the Mormon community” as she grew older and started drawing away. By contrast, she characterized her mother as “a kind of quiet heretic.” This made it “much easier for me. Her heresy was very quiet, and took the form mostly of encouraging me to be on my own. But this made for some family difficulties, too” (1975, 4).

Fawn, however, was involved with the Huntsville ward both spiritually and socially. According to Keith Jensen, a neighbor and long-time Huntsville resident, she taught a Sunday School class and frequently spoke or gave poetry readings as a member of the local congregation (K. Jensen 1988). Much of her recreation centered around the ward’s youth group, known as “the Builders Club.” It was here that she developed her long-lasting relationship with Dil worth Jensen. In Huntsville ward meetings, moreover, Fawn expressed her own religious beliefs. Her brother Thomas recalled that in a particular fast and testimony meeting, Fawn got up and “bore a beautiful testimony” asserting her belief in the truthfulness of the restored gospel (McKay 1986).

After graduating from Weber High School, Fawn enrolled at Weber College, a junior college in Ogden run by the Church. Fawn continued to excel in forensics and was a star debater, winning almost all of her debates. She traveled as far as Chicago to participate in intercollegiate contests. In 1932, sixteen-year-old Fawn and her older sister Flora graduated from Weber College together. Flora later recalled: “Our father was president of the Weber College board and he was so proud” when he presented his two daughters with their diplomas (Crawford n.d.).

Fawn entered the University of Utah in Salt Lake City in the fall of 1932.[3] As she recalled, “these were the deadliest of the depression years,” and she felt “lucky . . . to be in college at all” (1981, 86). Away from home for the first time, she and Flora shared an apartment a half mile below campus. At first, Fawn continued her debate activities, but during that first year “something happened,” she recalled, “to dull my appetite for confrontation and the heady satisfaction of winning.” Fawn developed “a revulsion at our debater’s practice of canvassing the documents on the nation’s suffering only for the purpose of finding arguments with which to win.” At this turning point, “whatever fleeting fantasies” she may have “had about going into law and politics, [although] never articulated” to her parents, “vanished at this point forever” (1981,90-91).

Fleeing from what she described as “both national . . . and personal problems,” Fawn turned inward to the “fantasy world of literature.” During what she characterized as “the three most rewarding months of study of my life,” she “read almost all of Shakespeare, a fair sampling of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Corneille, and Racine, and . . . developed a taste for Russian novels to which” she “later became an addict.” The “Gargantuan literary feast” revived her childhood dream of “writing great short stories and fine novels.” But this dream was dashed with “ineffable bitterness” as Fawn learned from her teachers that she had “no talent” for writing fiction. Later, she noted philosophically that “it was useful to have had it pointed out so early, though I clung for several years to the illusion” that this assessment was “in error” (F. Brodie 1981).

Fawn’s experiences at the University of Utah also began to create tensions with her heritage of Latter-day Saint beliefs. According to her older sister Flora, Fawn “began doubting the strong ties she had with the Church” (F. Brodie 1975; Crawford n.d.). In Fawn’s own words, “I was devout until I went to the University of Utah.” She began to move “out of the parochialism of the Mormon community.” But this separation “was tentative and constantly subject to testing.” She noted that the “Socratic questioning” of her philosophy professor, E. E. Erickson, “gently shook the faith of some of us who were devout, but did not raise tumultuous anxieties.” In one of her English classes, she remembered reading Milton’s Paradise Lost where Satan, despite being “wrong headed and vulnerable, had heroic qualities and was far more likeable than the omnipotent Jehovah.” The impact on her religious faith was “subtle but indelible.” In another English class, she recalled “the delicately worded criticism” of a professor who had encouraged her to write a research paper on the Latter-day Saint missionary system—a paper which she con ceded “had echoed only the propaganda of the faithful.” Fawn summed up her two years at the University of Utah as “a quiet kind of moving out into . . . the larger society and learning that the center of the universe was not Salt Lake City as I had been taught as a child” (F. Brodie 1975; 1981).

She did not discuss her growing doubts with her father or any other family member. According to Fawn’s younger sister, Louise, there was a complete absence of dialogue, particularly between Fawn and her father. Whenever Fawn would attempt to raise questions, the only thing her father would say was, “You’ve got to believe” (Card 1986). She later recalled in a 4 November 1959 letter to her uncle Dean Brimhall, “We both found it impossible to communicate on the subject, as on most others.” She attributed this lack of communication to a McKay family tendency to avoid unpleasant matters.

Fawn completed her university studies in 1934 and was awarded a bachelor of arts degree in English with high honors (joining Phi Kappa Phi, the scholastic honor society). At the age of eighteen the new graduate returned to Ogden and Weber College to teach English for the modest salary of sixty dol lars a month. Although she was younger than most of her students, her cousin Jeannette McKay Morrell (a college English teacher herself), recalled in a letter to Fawn’s sister Barbara that Fawn “did a beautiful job” and “taught rings around a great many of the long-established teachers” (Morrell n.d.).

But her doubts persisted. According to Flora, Fawn “began looking into the history of the Church . . . particularly the founder Joseph Smith.” This, in turn, affected her still flourishing relationship with Dilworth Jensen. Dil worth had been called to the Swiss-German Mission at the beginning of Fawn’s freshman year at Weber College, and Fawn had maintained close contact through weekly letters. He returned home in June 1933, enrolled that fall at the University of Utah, and was, thus, with Fawn her senior year. When Dil worth completed his bachelor’s degree in zoology in June 1935, both he and Fawn were awarded graduate fellowships at the University of California at Berkeley. They even talked of marriage (P. Jensen 1988b).

But Fawn’s persistent questioning of Latter-day Saint beliefs created difficulties. Dilworth, firmly committed himself to Church tenets, became “very frustrated and worried” as he observed Fawn’s problems with Church history and doctrine. Fawn, her strong attachment to Dilworth notwithstanding, was concerned about their present and future religious compatibility (F. Brodie 1980; P. Brodie 1988; P. Jensen 1988a). A potential impasse was averted when Flora, over her parents’ objections, eloped with Leslie Jensen, Dilworth’s older brother. The McKays apparently feared that Fawn and Dilworth might follow their course, and so Fawn and her parents mutually agreed that she would not go to Berkeley but would instead attend graduate school at the University of Chicago (Crawford 1986; P. Brodie 1988; P. Jensen 1988a).

Fawn’s departure for Chicago was undoubtedly the turning point in her life. Living away from Utah for the first time, “she met . . . people with tremendous intellectual curiosity and completely open minds” (B. Brodie 1983). But at the same time, she maintained ties both with Church members and Utahns. She was active in the “Utah Club,” a group of University of Chicago students who occasionally got together socially (Larson 1988). She also continued certain Latter-day Saint practices despite her doubts. According to Fawn’s daughter, Pamela, Fawn prayed every night before going to bed (1988). Fawn, moreover, continued to correspond on a daily basis with Dil worth, at Berkeley pursuing his own graduate studies (F. Brodie 1980; P. Jensen 1988b).

However, Fawn asserted her independence from her Mormon heritage with some apparent success:

the confining aspects of the Mormon religion dropped off within a few weeks … . It was like taking off a hot coat in the summertime. The sense of liberation I had at the University of Chicago was enormously exhilarating. I felt very quickly that I could never go back to the old life, and I never did (F. Brodie 1975, 3).

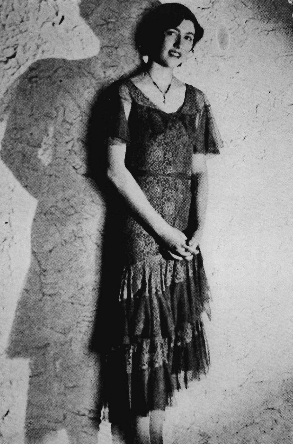

And after she met fellow student Bernard Brodie, she completely severed her relationship with Dilworth Jensen. She was working in the school cafeteria, serving free second cups of coffee—a job that she got because she was tall and could be seen across the large dining hall—when a mutual friend introduced her to Bernard. He was immediately attracted to Fawn, who was not only very intelligent but statuesque, beautiful, and sociable.

In turn, Bernard was unlike anybody Fawn had ever known in Utah, having grown up in Chicago “surrounded by tenements . . in a lower-middle-class family” of Latvian-Jewish immigrants (Berges 1977). But like Fawn, he was articulate, extremely bright, and charming. According to their son Bruce, Bernard was “quite a romantic, and along with bringing [Fawn] flowers each day, would recite poetry to her and take her horseback riding in the parks” (1983, 5-6). Fawn’s parents had strong reservations about the match. Flora recalled that the McKay family fasted and prayed for a week that the objectionable marriage would not come to pass (Crawford 1988). But it was a whirlwind courtship.

On 25 August 1936, the day that Fawn received her M.A. in English and after a mere six weeks of courtship, Fawn and Bernard were married in Chicago, interestingly enough, in the local Mormon ward. Fawn consented to be married there, despite her growing alienation from the Church, in order to please her mother (P. Brodie 1988). Indeed, Fawn’s mother was the only one of either set of parents to attend the wedding. “And she,” according to Bruce Brodie, “came from Salt Lake City to Chicago as much to talk my mother out of it as to attend the wedding” (1985, 5). Pamela Brodie recalls her mother telling her that because the local Mormon ward served as the site of the wed ding, Bernard’s side of the family was offended, particularly his mother and brothers who declined to attend (P. Brodie 1988). However, Bernard Brodie’s younger brother, Leonard, recalls that tensions and conflicts within the Brodie family itself were more responsible for his family’s decision not to attend (L. Brody 1988). Whatever the case, Fawn was only twenty and according to her son, “had to lie about her age to get her marriage license” (1983, 5).

Shortly after her marriage, the new Mrs. Brodie began the research which led to the publication of No Man Knows My History seven years later. To some extent, her initial research on the life of Joseph Smith was an effort to answer the questions of a husband “totally new to the Mormon scene. . . . Answering his questions,” Fawn later noted, stimulated her “to find out the roots and sources of what Joseph Smith’s ideas were.” She started out “not to write a biography of Joseph Smith but to write a short article about the sources of the Book of Mormon.” But, as she pursued her research, she found there was “no good biography of Joseph Smith” and so undertook the task her self (F. Brodie 1975, 6-7).

Researching and writing about Joseph Smith would moreover enable Brodie to secure independence from her Mormon heritage and thus relieve the tensions between her secular learning and what she perceived as the apparent naivete of Mormon beliefs. Her questions, although long antedating her marriage to Bernard Brodie, intensified as she pursued her research and writing following her graduation in 1936. Since Bernard had not completed his doc toral program, she remained at the university and secured a job in the school library entailing minimal duties. Fawn was left with a significant amount of time for her own pursuits.

During these years, she was particularly close to her uncle, Dean Brimhall, her mother’s younger brother. Brimhall, a Columbia Ph.D. in psychology, was then an administrative assistant in the Department of Labor Management of the Works Progress Administration. As he was also known as a free thinker and critic of various aspects of Mormon doctrine and practice, Fawn felt comfortable confiding to him her doubts and concerns.

In 1937, following Brimhall’s lead, Fawn took an interest in the Church Security Program (later known as the Welfare Program), at the time touted by Church leaders as a Mormon version of the WPA. The Church Security Program was initiated in April 1936 in reaction to the anticipated curtailment of federal relief. Although this program aided many destitute Church members, both Brodie and Brimhall felt that Church officials overstated the pro gram’s impact in taking Church members off federal relief rolls. Their point was that the Church was deliberately creating the illusion that it had removed “most or all of its members from public assistance” rolls through its Welfare Program (F. Brodie 1937). But in reality, the number and percentage of Church members receiving public assistance remained high. Brimhall, who studied the issue carefully, remarked to a friend in late 1937 that “only six states had a ‘higher load’ on the Emergency Works Program than Utah.”[4]

Prompted and encouraged by Brimhall to make her own study of the problem, Brodie arrived at the same conclusions but also suggested in a 13 April 1937 letter to her uncle that the Church, in collecting tithes and other donations to be used in its relief efforts, was “actually making money on the whole business.” In this same letter, she confided that “I have been working up this paper which I hope will be worthwhile to someone if it ever sees the light of publication.” But if it were to be published, she continued,

I shall take the utmost pains to prevent anyone from home discovering who wrote it. I have too deep a regard for daddy and mother to let them know my present attitude toward the plan, and the Church as a whole, especially since I am trying to make a minor move against it.

But then she concluded, “It’s all very complicated and sometimes a little sickening.” Brodie’s inner conflicts were clearly evident.

Latter-day Saint activity in Nazi Germany during the late 1930s further alienated her. Brodie’s reaction had a familial aspect, due in part to her immediate family’s “quasi-German heritage.” Thomas E. McKay had served two Church missions in Germany: the first during the 1890s and the second just before World War I, when still unmarried and in his mid-thirties, he was called as president of the Swiss-German mission. Indeed, it was during his second mission in Germany that he met his future wife, Fawn Brimhall. She had been vacationing in Europe and had stopped off in Germany to visit her missionary brother Dean, who then introduced his sister to Thomas McKay. In the late 1930s, Brodie’s younger brother, Thomas B. McKay, was also called as a missionary to Germany, and shortly thereafter the Church dispatched her father to Switzerland to serve first as president of the Swiss-German mission and then as president of the Swiss-Austrian mission. The elder McKay’s jurisdiction eventually came to include Church affairs not only in Germany but elsewhere on the continent.

Fawn Brodie, therefore, had more than a passing interest in pre-war Nazi Germany. The Church’s position there had become increasingly precarious as Nazi officials placed more and more restrictions on Church activities. Alfred C. Rees, mission president for eastern Germany, attempted to ease the situation by currying favor with Nazi officials. In early 1939 he wrote an article describing those features within Mormonism he thought would appeal to Ger mans. His article, “In the Land of the Mormons,” was published in the Nazi Party’s propaganda sheet, the Volkischer Beobachter. Brodie, made aware of this controversial development by family members close to the scene, was further distressed to learn that “Rees has encouraged all of the missionaries to write [similar] articles for the local [German] newspapers.” In a 14 June 1939 letter to Dean Brimhall, Fawn commented on the semi-official Church position vis-a-vis the general German situation: “If the Deseret News is careful not to offend Germany, and I gather from your statements that it is falling over back wards on the attempt, it is my guess that first of all the Church is afraid of complete banishment.”

Brodie continued in this same letter to comment on the critical situation of German-Jewish refugees as Nazi persecution intensified during the late 1930s. The Church, she complained, did not confront this issue editorially in the Deseret News and thus appeared oblivious to its moral dimensions. Al though Brodie was also sensitive to the difficulty of the Mormon position, noting that “the Church [in Germany] can ill afford persecution at this moment,” she also attributed Latter-day Saint evasiveness to “the latent anti Semitism which exists in every area as provincial as Utah and which is not dispelled by the Church doctrine that we are all of the ‘blood of Israel.’ ” She ended the letter with a touch of ironic sarcasm: “I can just hear the good brethren .. . at home saying—’of course the persecution of the Jews is terrible but God moves in mysterious ways, his wonders to perform.’ ”

On this issue Brodie once again reflected her own ambivalence. On the one hand, she was very aware of the Church’s quandary in Nazi Germany—difficulties that directly involved her immediate family. But, at the same time, she was indignant at what she perceived as Latter-day Saint indifference to the German persecution of the Jews— an issue that assumed particular relevance by virtue of her marriage to Bernard.

During the same period, Bernard himself found it difficult to secure an academic position, despite his intellect and his Ph.D. in international relations from the University of Chicago. According to his son Bruce, Bernard attributed the difficulty “at least in part” to being Jewish since “at that time many institutions still openly discriminated against Jews” (1983, 7). Eventually Bernard was offered a position at Dartmouth College, and in 1941 the Brodies moved to Hanover, New Hampshire.

Encouraged by her uncle Dean Brimhall, apparently Fawn had begun to think seriously about writing a biography of Joseph Smith in late 1938 or early 1939. In the same 14 June 1939 letter Dean Brimhall mentioned above, she also outlined the research she had completed and added, “I hope sometime to be able to turn out a genuinely scholarly biography.”

But the biography would be no mere academic exercise. By this time, Joseph Smith had become the focus of her accumulated grievances. Convinced that he “was not a true prophet” and that she had found real answers, Brodie would flesh out her convictions and supply her answers in an account of his life that would invalidate his claims to a divine mission. This would enable her not only to reject Joseph Smith and hence the authority of the Church, but also to satisfy her need to understand and explain by supplying a naturalistic interpretation of his life. Once an alternate version was in place, she could free herself from all the baggage of Mormonism.

According to her son Bruce, Fawn “felt an intense sense of betrayal but was working through in a way an equally intense childhood love for [Joseph Smith] who had been vitally important [to her] as a young Mormon” (1983, 12). Brodie in 1975 maintained that she had been “conned” and two years later elaborated that she “simply had to know whether I’d been taught the truth, years earlier in Sunday School” (F. Brodie 1975; Berges 1977). “The whole problem of his credibility,” Brodie maintained, “was crying out for some explanation” (1975, 7).

Smith’s credibility was apparently further undermined in Brodie’s eyes by the results of concurrent research being done by scholars on the life and activities of James Jessie Strang—the schismatic Mormon leader. M. Wilford Poul son, a professor of psychology at Brigham Young University, whom Brodie knew well and corresponded with, had decifered the coded portions of Strang’s “Diary,” revealing a different, albeit mercenary side of Strang contrasting to his public image of religious piety. According to writer Samuel W. Taylor, the diary revealed Strang to be “intensely ambitious but frustrated until he deliberately became a fake prophet strictly for what was in it for Strang—the pomp and trappings of authority, the wealth from tithes, the adulation of the flock and the choice of pretty girls for plural wives.” Taylor later recalled that Brodie “learned of Strang’s code from Poulson and applied Strang’s attitudes to Joseph Smith” (1978, 232).

In retrospect, Fawn Brodie summarized her varied motives for writing her biography of Joseph Smith:

It was a rather compulsive thing. I had to. It was partly that I wanted to answer a lot of questions for myself. There were many questions that no one had answered for me. I certainly did not get any of the answers in Utah. Having discovered the answers and being excited about them, I felt that I wanted to give other young doubting Mor mons a chance to see the evidence. That, plus the fact that I had always wanted to write, made it possible—not made it possible—made it imperative that I do a serious piece of history (1975, 10).

In explaining to Dale Morgan why she wrote the book, Brodie placed her motives in a somewhat different perspective. In a 23 May 1946 letter to Juanita Brooks, he passed on Fawn’s explanation that the biography served her the same way “the autobiographical novel serves many other writers; it has been a kind of catharsis” (Walker 1986, 121). The ambivalence, however, did not go away. She admitted that “there was always anxiety along with [this work] because I knew it would be difficult for my family.” And she added, “I . . . always felt guilty about the destructive nature” of the book. But at the same time, she confessed that she found the “detective work” involved in exposing Joseph Smith as a “fraud” or “imposter” to be variously “fun,” “fascinating,” or “exciting” (F. Brodie 1975, 10, 15; 1939).

Brodie’s inner conflicts were reflected in other ways as she got deep into her research and writing. In a 14 October 1943 letter to her fellow author and close friend, Claire Noal, she confessed: “More and more I am coming to believe that the great biography of Joseph Smith will be a fictionalized one.” She continued: “There is plenty of evidence to write a book without fictionaliz ing, but to bring to life the man’s inner character, to display all the facets of his infinitely complex nature, requires I think the novelist’s perception rather than the historians digging.” Brodie then concluded “I shall have to be content with the latter.”

Despite such conflicts (or more properly, because of them), she completed the biography. It took her approximately seven years from late 1938 (or early 1939) until its publication in November 1945. The “major research” was done in the University of Chicago Library, which had “a great collection” of western New York State history. Brodie also made extensive use of materials in the New York State Library at Albany, the New York Public Library, and the Library of Congress. She also examined materials in the Huntington Library, Western Reserve Library, the library of the Reorganized LDS Church in Independence, Missouri, and in the collection of the LDS Church Historian’s Office in Salt Lake City (F. Brodie 1945, xi).

Brodie apparently began synthesizing the results of her research after the Brodies moved to Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1941. She had the assistance of both her husband Bernard and Dale L. Morgan in this difficult task. In her 14 June 1939 letter to Dean Brimhall, Fawn credited her husband with pro viding “a detachment” she could “never have” and acting as “a first-rate literary critic.” According to her acknowledgments, he “read the manuscript many times, each time effecting some improvement in its literary qualities” (F. Brodie 1945, xi).

Fawn also relied heavily on the help of Dale L. Morgan, whom she first met in 1943 when they were both living in Washington, D.C. Brodie and Morgan became immediate friends with Morgan quickly assuming the role of mentor. Morgan “went through the manuscript with painstaking care,” utilizing his skills as “an exacting historian and penetrating critic” (F. Brodie 1945, xi). Moreover, both Bernard Brodie and Dale Morgan exerted a moderating influence on Fawn, urging her to be less negative in her assessment of Joseph Smith. In a 29 January 1979 letter to Revere Hansen, Brodie disclosed:

The volume would have been a harsher indictment of Joseph Smith had it not been for [Bernard’s] influence. I was angered by the obvious nature of the fraud in his writing of the Book of Mormon; I felt that his revelations all came out of needs of the moment and had nothing to do with God, and I thought the frantic search for wives in the last four years of his life betrayed a libertine nature that was to me at the time quite shocking. My husband kept urging me to look at the man’s genius, to explain his successes, and to make sure that the reader understood why so many people loved him, and believed in him. If there is real compassion for Joseph Smith in the book, and I believe there is, it is more the result of the influence of my husband than anyone else.

Dale Morgan assessed a preliminary draft of Brodie’s manuscript as “over simplified in its point of view.” Morgan told her in his undated letter,

I am particularly struck with the assumption your ms. makes that Joseph was a self conscious imposter. . . . Your own point of view is much too hard and fast, to my way of thinking; it is too coldly logical in its conception of Joseph’s mind and the develop ment of his character. Your view of him is all hard edges, without any of those blur rings which are more difficult to cope with but which constitute a man in the round.

He proposed that the biography

should be so written that Mormon, anti-Mormon, and non-Mormon alike can go into the biography and read it with agreement—disagreeing often in detail, perhaps but observing that you have noted the points of disagreement and that while you set forth your point of view, you do not claim that you have Absolute Truth by the tail.

However Brodie may have moderated her assessment of Joseph Smith, it was not enough for the leaders of the Church. In May 1946, six months after the publication of No Man Knows My History, the Church moved to ex communicate her. Two Mormon missionaries came to Brodie’s home in New Haven, Connecticut, with a letter asking her to appear before a bishop’s court in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to defend herself. According to her account, she “simply wrote in reply that I would not be present,” later adding “because after all, I was a heretic.” She was then “officially excommunicated and got a letter to that effect” (1975, 4; 27 May 1946.).

Although it seemed that Fawn Brodie had achieved her long-sought independence from Mormonism, even at this critical point, she manifested apparent inner conflict. According to Wallace Stegner’s account, later corroborated by Fawn herself, “she came to Dean Brimhall in tears, and . . . could hardly be comforted because she was so disrupted to be disfellowshipped” (1983, 109-10). Aware that her uncle had relayed the details of this incident to her mother and father, Fawn wrote them 2 June 1946, “I hope Dean didn’t give you an exaggerated picture of my own attitude. It was just that I could see so clearly what it might mean for you and Daddy. . . . I felt badly about it in the beginning because it seemed to symbolize how completely I had burned my bridges behind me.” She never associated with another church. Years later, in an 18 October 1967 letter to Monseigner Jerome Stoffel, Brodie confessed that she had dismissed all religion as “only a complication in my life,” asserting that “abandoning religion altogether has been a wholly liberating experience.”

But the independence was less than complete. According to her brother Thomas B. McKay, Fawn “never really left her Mormonism behind” (1987). She continued to embrace values and behavior which, although universal, received special emphasis within the Latter-day Saint community. For ex ample, maintaining strong family bonds was important to her. Fawn and Bernard, despite what their son Bruce called “not an easy marriage,” remained together for forty-two years until Bernard’s death from cancer in 1978. Fawn’s desire to forge strong family bonds was also reflected in the way in which she related to her children. Although she enjoyed and needed the stimulation of research and writing, Fawn was acutely aware of devoting the time necessary to be a good mother to her three children: Richard, born in 1942; Bruce, who came along in 1944; and finally Pamela, who was born in 1950. She asserted on more than one occasion that being a mother gave her much greater satisfaction than writing books. “Children are more rewarding than books,” she declared. Unlike children, “once a book is finished it is the deadest thing in the world” (F. Brodie 1975, 47-48). Thus, during the years they were growing up, her children took priority over the research she was doing for her second biography on Thaddeus Stevens, the radical Reconstruction leader.

Brodie also shared the Latter-day Saint emphasis on community involvement. “A political activist,” she was “more liberal and far more closely identified with student causes than her political scientist husband” (Van Wagoner 1982, 36). She was also concerned about the natural environment. Brodie, moreover, not only proclaimed the Mormon “work ethic . . . one which I greatly admire.” Judging from her five major books, teaching, community activities, and her family responsibilities, it was one to which she strongly sub scribed. Brodie admitted to working “extremely hard,” attributing it to “some kind of mad, inner compulsion which has to do with God knows what” (1975, 46). On another occasion, she described herself as a “compulsive woman racing around frantically,” asking rhetorically, “Why do I do it? Because Fm unhappy when I’m not doing it” (in Berges 1977).

Brodie’s Mormon background, moreover, had an influence on the approach she took in her four later biographies. In her second biography, Thaddeus Stevens, Scourge of the South (1959), she attempted to rebuild the reputation of a man whom she felt “had elements of greatness” but had been “abused and vilified by history.” Brodie confessed that this was “a total about face” in terms of what she had done earlier with Joseph Smith. With Smith she had brought down to earth a man whom she felt “did not deserve” the reputation that he had among the Latter-day Saints. In contrast, by writing about Stevens, Brodie was pleased “to be doing a positive rather than a destructive thing” as she “had always felt guilty about the destructive nature of the Joseph Smith book” (1975,15).

Brodie’s third biography, The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton (1967), also had a connection with Utah and the Latter-day Saints. Burton, a nineteenth-century British explorer and anthropologist, had had an intense interest in varied (some would say deviant) sexual customs. To pursue this interest, Burton had visited Utah in the 1860s to observe Mormon polygamy. His account appeared in his book, The City of the Saints. In the early 1960s, Alfred Knopf decided to reissue this volume and asked Brodie to edit and write the introduction. Brodie soon found Burton “fascinating beyond belief” and pushed ahead with a full-scale biography that she completed in 1967 (1975, 66-67).

In researching Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History, her fourth biography, she recognized parallels to her own life as the daughter of a prominent Church leader. In interviews given shortly after the book’s publication in 1974, Brodie noted that “when I examined Jefferson’s life, I had a sense of deja vu” in that “I’m obliged to admit important resemblances between Jefferson and my father.” Like Jefferson, Thomas McKay “exhibited deep affection for his offspring along with equally strong expectations” (Eckman 1974). Both men “insisted on orderliness. Both stressed self-control. Both admired ‘adoring, deferential daughters.’ Both were chronically in debt.” She acknowledged that Jefferson “reminded me of the way I was brought up. My father was a gentle, courtly man, but a benign despot in his own family. Just as Jefferson was” (in Hano 1974,4).

Brodie also took note of certain parallels in the controversial nature of her research on Jefferson, comparing it to her earlier work on Joseph Smith. She did this in outlining her approach in relating “the story of [Jefferson’s] slave family by Sally Hemings, as well as a proper accounting of his wonderful love affair with Maria Cosway in Paris.” She noted that in taking this approach “the problems are major, and I find the Jefferson establishment at the University of Virginia almost as protective of Jefferson as were the brethren in Salt Lake City protective of Joseph Smith” (F. Brodie 1971).

Brodie’s final biography, Richard Nixon: The Shaping of His Character (1981), also echoed back to Joseph Smith in certain respects. As had been the case with Joseph Smith, Brodie found Nixon to be a “very, very complicated man” (F. Brodie 1975, 40). She saw Nixon as she saw Joseph Smith: a man who presented himself as something more than what he was. Nixon was a “man who promised to bring truth to government” but who entered “into a situation of telling so many lies.” This paralleled her interpretation of Joseph Smith’s quest for religious truth and his subsequent covert practice of Mormon polygamy. Brodie was intrigued by another facet of Richard Nixon’s life, “the intensity of affection for the man” by people who “supported him through his career” and who were “still supporting him” even in the wake of the Watergate Scandal (Berges 1977). Like Nixon, Joseph Smith’s integrity and credibility had been questioned and carefully scrutinized, but unlike Nixon’s case, this had been going on for over a century with a parade of critics and skeptics, including Brodie herself, exposing his weaknesses and contradictions. But, despite such disclosures, devout, practicing rank-and-file Latter-day Saints retained their affection for him, and the Church continued to grow.

Thus, Fawn Brodie was never truly independent from Mormonism. Even as she was dying of cancer in late 1980 and early 1981 and struggling to finish her biography of Richard Nixon, two stories circulated concerning her past and present relationship to the Church. The first suggested that immediately following the appearance of No Man Knows My History in 1946, Brodie had asked to be excommunicated from the Church and that in purging her name from the Church rolls, Church officials were merely acquiescing to her request. This, of course, was untrue.[5]

A second story, circulating in early 1981, was that Brodie had asked to be rebaptized. (Versions of this story had circulated since the publication of No Man Knows My History.) What gave renewed impetus to the rebaptism story was the late December 1980 visit Thomas B. McKay made to his sister, who was gravely ill in St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica. According to Brodie’s 1980 account, “I was very glad to see [Thomas] and asked for a blessing—as my father had communicated blessings over the years as a kind of family patriarch. This blessing he gave me, and I told him I was grateful, saying he had said what I had wanted him to say.” Her account reveals her lingering inner conflict: “My delight in asking for an opportunity for a blessing at that moment indicated simply the intensity of an old hunger.” But she care fully added: “Any exaggeration about my requests for a blessing meaning that I was asking to be taken back into the Church at that moment I strictly repudiate and would for all time.”[6]

On 10 January 1981, Fawn Brodie died at the age of sixty-five, and in accordance with her wishes, her body was cremated and the ashes scattered over the Santa Monica mountains she loved near Pacific Palisades where she had spent the last thirty years of her life.

Fawn McKay Brodie was never able to free herself completely, despite having written No Man Knows My History and despite being excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This failure can be attributed, in part, to the close ties she maintained with her parents, sisters, and brother who all remained in the Church. Also, Brodie herself shared many of the distinctive values of devout, practicing Latter-day Saints. And finally, she had emotional ties from which there was no escape. She seemed to recognize this in admitting to her brother, Thomas B. McKay, “that once you’re a Mormon you can never escape it” (McKay 1987).[7]

[1] Aside from Shirley E. Stephenson’s oral history interview of Fawn Brodie, her sisters and brother are the most useful sources for her early life. Flora McKay Crawford has recorded her memories, “Flora on Fawn,” and in 1982 Barbara McKay Smith presented an address, “Recollections of Fawn M. Brodie,” to the Alice Louise Reynolds Forum, Provo, Utah.

[2] There is some confusion about the children’s publication that published Fawn’s poem. She told Marshall Berges that it was “a Mormon church children’s magazine” (1977, 8). However, according to Flora McKay Crawford (n.d.), the poem was published in Child Life, a nonreligious journal published in the Midwest.

[3] Fawn Brodie’s experiences at the University of Utah are vividly described in “It Happened Very Quietly,” including in Remembering, The University of Utah (1981).

[4] See Heinerman and Shupe (1985, 181-87) for an account of the Church Security Program.

[5] At the time of Brodie’s death on 10 January 1981, the Associated Press reported that she “had requested excommunication.” See: “Fawn McKay Brodie Dies; Known for Biographies of Jefferson, Mormon Leader,” Washington Post, 13 January 1981. Barbara McKay Smith’s rebuttal to this claim appeared in a 19 January Associated Press article, “Relatives of Fawn Brodie Dispute Statement on Excommunication.” She stated that Brodie “had never asked to be excommunicated but had chosen not to answer a summons in June 1945 to an ecclesiastical trial called by her local church leaders in Cambridge, Mass.”

[6] Indeed, Fawn Brodie’s own children, who kept a close watch over their mother during the last weeks of her life, minimized the religious implications of this blessing. According to Pamela Brodie, her mother’s cancer had by this time moved into her brain, and this, combined with the heavy medication that she was under, caused her to “hallucinate.” Pamela believed this was the condition Fawn was under when she requested a blessing (P. Brodie 1988).

Bruce Brodie, in a 30 November 1988 letter, concurs, noting that his mother “was suffering from an organic brain syndrome when this incident occurred, due probably to a com bination of heavy medication and cancer metastasis in the brain.” He added: “During the last weeks of her life, either my brother, my sister, or I were with her nearly twenty-four hours a day. None of us ever heard her mention the Mormon Church or anything remotely related to it. For that matter, she never ever talked about God or heaven.”

Bruce Brodie, moreover, characterized his mother’s request for a blessing on another level—that is, as a “gift” that she chose to “give” her brother. In explaining this, he noted that “When my mother saw her brother she spontaneously asked him for his blessing.” Brodie compared his mother’s behavior to her actions toward her younger sister Louise Card, noting that “when she saw my Aunt Louise (who has always loved fancy clothes), [Fawn] modeled a new hat for her. As my aunt wisely pointed out, ‘She gave a gift to each of us.’ Asking my uncle for his blessing was just that: a gift to him.” Bruce Brodie took care to emphasize that his mother’s request for a blessing “was in no way an indication of any ambivalence toward the Mormon Church” (B. Brodie 1988).

[7] Again, Brodie’s children minimize the significance of the interaction that their mother had with “things Mormon” during the course of her life. Fawn’s son Bruce concedes that during the “first half” of her life “the Mormon Church held a fascination for her, as it does for many ex-Mormons.” But he continues that “during the second half of her life she lost even that fascination with the church.” He concludes: “She gladly accepted honors from Utah historical groups and would occasionally read Mormon history when requested. But she had no real interest of her own” (B. Brodie 1988).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue