Articles/Essays – Volume 02, No. 2

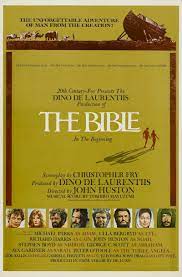

Finding Yourself at the Movies | John Huston, dir., The Bible: In the Beginning . . .

I have seen The Bible and I believe in it as far as John Huston has translated it correctly. He is sometimes like DeMille and other scriptural movie makers—sugar coating, sentimentalizing, pompous piety—but most of his Bible, especially the first half, is obviously the work of a director determined to make a movie and not a pageant.

It begins promisingly with spectacular shots of floods, waterfalls, volcanoes, and other awesome phenomena, to the accompaniment of Huston’s voice reading the words of the Creation. This is almost too promising, because the bulk of the picture does not exploit this promise of reconciling the differences between literal scripture and natural law.

The Adam and Eve story is tastefully and imaginatively enacted. The best moment of the entire three hours, in fact, is “And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground,” in Huston’s ingenious cinematic translation.

Our first unpleasant jolt is Richard Harris as Cain. As he seeks to escape the wrath of the Lord after his inconsiderate treatment of Abel, he is pursued by a camera mounted in a helicopter, and for this hovering audience he performs the darnedest series of brow-clutchings and posturings since W. C. Fields in The Old-Fashioned Way.

But then Huston himself appears as Noah and gives us a folksy and charming depiction of the people of the Ark. He achieves a quirky authenticity, so that you think, as you see him step off the cubits and make that unlikely vessel take shape, “By golly, he’s probably really using gopher wood.” The film arrives at a beautiful natural ending with the Ark on Ararat and the wonderful animals escaping into unfamiliar territory.

Unfortunately, the film does not end here. Modern theatre economics demands three hours, warranting both high prices for tickets and intermissions for the snack-bar trade. So we continue with the Tower of Babel, justifiable perhaps as the sort of “spectacle” audiences expect of Biblical epics—scaffolds and beards flying in the wind, stuntmen dropping off cliffs in careful one-and-a-halfs, thousands of extras bullhorned by assistant directors into vast patterns of pointless movement.

Huston’s Bible (a mere twenty-two chapters of Genesis, leaving much to challenge future directors and extras) concludes with Abraham, Sarah, and Isaac. Huston by now is tiring, and when the classic words of the Abraham Sarah-Hagar triangle come alive on the screen we think of Peyton Place and what folks tell the neighbors when something funny’s been going on. And Lot’s wife turns not to salt but to some kind of wind-whipped papier mache. Abraham and Sarah are credibly acted by George C. Scott and Ava Gardner (yes, by golly, she gets away with it), but somehow in the translation from familiar Bible Story to Big Screen in Color, Scott with the knife upraised be comes a nutty old man and it becomes hard to find God in all this.

For all its moments of cinematic flair, Huston’s Bible is safe and fundamental. We might have expected this daring director to do something unexpected, like showing us where Cain’s wife came from, or why God plagues everybody who believes Abraham’s story about Sarah being his sister. But in the end we see that Huston is no Hugh Nibley. His world is crime, as in The Maltese Falcon and The Asphalt Jungle, and the sooner he gets back to it the better.

Strangely, there is no message of morality in this major scriptural movie, beyond the simple rule of obedience. For moral thought-provoking I recommend A Man for All Seasons, although I’m skeptical of martyrs and their motives. According to Robert Bolt’s screenplay, Sir Thomas More died for two principles: the sanctity of the civil law, which makes him seem noble to men; and the Pope’s objection to Henry VIII’s divorce and remarriage, which makes him seem silly. Disapproving of Henry’s peccadilloes is understandable, but carrying one’s disapproval to the point of having one’s head chopped off and making one’s wife and daughter husbandless, fatherless, and homeless seems to me to be extravagant.

Having noted this personal quibble, I can report that A Man for All Seasons is a superb movie. Paul Scofield portrays More not only with great technical skill but also with the charm of personality that makes you care what happens to him. Fred Zinneman has directed with meticulous craftsmanship, so that More’s whole era springs to life around him. As Cromwell, Leo McKern does a serious version of the oily burlesque villain he played in the Beatle movie Help! And Robert Shaw makes Henry VIII a willful, dangerous, spoiled baby, a universal kind of tyrant as recognizable among men of power today as among sixteenth century royalty.

Anybody will find A Man for All Seasons an engrossing movie. A devout Catholic, or anybody who can accept the remarriage of Henry VIII as a symbol of moral principle relevant to the twentieth century, like, say, the Loyalty Oath, will also find it a memorable dramatization of human dignity.

But for morality that applies to us and our era I would direct you not to these big “religious” pictures but to small and penetrating and unpretentious examinations of twentieth century life like Alfie, Darling, and Georgy Girl. In Abraham and Sir Thomas More you will find the enduring stuff of myth, but in Alfie and Darling and Georgy Girl you will find yourself.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue