Articles/Essays – Volume 38, No. 1

Flying in a Confined Space

In my dream, people mill at a fair, trying things they’ve never before done. There’s horseback riding on flashy steeds and archery with brightly fletched arrows.

At the fair’s farthermost edge, wings rest upon the green. Their colors—kite colors—catch at me. I cross the field whispering, I’ve always wanted to try this! An attendant helps me strap into the hang-glider. I snap helmet and goggles in place and cast myself to the wind.

Well, it turns out I’m a natural. Within me wakes the Aufklarung of flight, of orientation with the horizon and fearlessness in the face of movement ungrounded. I spin course by stars I cannot see and trust in winds I do not control. Over the green I soar, in accord with a finely drawn yet constantly changing map in my blood. I both follow and make the map as I go.

Suddenly, there’s a wall! I wheel to the right, only to find another, rising hundreds of feet into the air. I turn on a wingtip and circle, but—another wall! What do they mean?

Looking up, I realize that the odd tint to the sky is the shadow of a vast ceiling. Skylights bubble outward, permitting glimpses of free air, yet it is a ceiling all the same.

I fly within these confines, skillfully using the space, but my condition has been reduced to that of a swallow trapped in a barn. Looking at the skylights, I think, I must get my wings into that blue.

***

Capitol Reef National Park, Chimney Rock Trailhead, September 1999. The rain that muddied the trail earlier has dried off, leaving little sign of its passing. Good footing on the trail is a must: I’ve been away from the desert for a long time and have gone out of shape. I’ve been away from almost everything.

I walk over to study the map board. Another trail branches off the Chimney Rock Loop, veering into Spring Canyon. My eyes linger over the spot where the trail splits. I’m tempted, but tell myself, Just the loop.

On the phone, Mark said everything was going “okay,” a word that I knew reflected worry but which was meant to encourage me to get what I needed from my first trip away from home in seven years. He said our daughter, Mattea, had slacked off her feedings. Which means, soon she’ll stop altogether, unless Mom—me—arrives to restore normalcy.

Isn’t as bad as it used to be. Used to be, if the formula we fed her was a few degrees too warm or too cold or if its ingredients changed slightly, she would go on a hunger strike. Possibly the turmoil such differences caused were not mere fits of tantrum, but discomposure—her injured brain’s inability to settle with that with which it is not exactly familiar. She may have had a sensory dysfunction in her mouth.

Whatever the case, such days-long fasts resulted in dehydration and combative behavior, followed by severe constipation and her screams of pain and terror. Sometimes we had to manually evacuate her bowels. The trauma burned off any progress she had made; we’d have to channel weeks of effort into helping her recover what she lost.

Used to be, feeding her took two hours per meal. Six hours a day for three meals, forty-two hours a week: nearly two days’ time out of every seven. Some weeks I figure it did total two full days. I crushed the rest of my life into the three-to-four-hour intervals between feeding times. The job of getting food into Mattea fell to me because she and I worked out a rhythm for feeding I couldn’t explain and no one could duplicate, and also because she’s rigid, tolerating no sudden change.

Since I left on this trip—my first time away since her birth—she has allowed Mark to feed her a few meals. Don’t know why she lets him for some but not for all. Now when such disruptions occur, they’re less severe and she recovers more quickly. Before daring to venture from home, I took care to “tank her up.”

To the southwest, aspens burn where fall has kindled in the high forests of the Aquarius Plateau. Yellow flames sweep through the trees in seemingly unbroken waves.

Here at the park’s lower elevations, pinon pines and junipers stand apart. Their night-wet greens and shadow blues mix with dry shades of rice grass, shad scale, and purple aster. Silver-green clusters I can’t name break from the brick-red soil. Everything shimmies in an early morning canyon wind.

Just the loop.

As I set out, the ground changes color from terra cotta red to clayey gray green. I’ve crossed my first threshold, one that spans hundreds of thousands of years. On our geological time palette, the colorful strata along this trail are named Moenkopi, Shinarump, Chinle, Windgate, and Kayenta. All around, time lies petrified in a sandstone spectrum. Above arches the blue empyrean formation of stratified gases and light. The whole works enchants the eye. As I climb the steep switchback that jags through the gray-green formation, my appetite for being here rises.

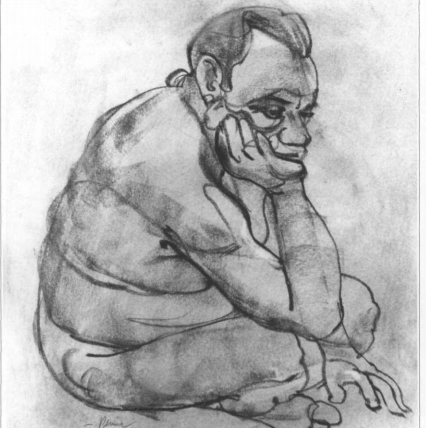

But the going isn’t easy. As the sign said, this trail is a three-mile loop, semi-strenuous, and I have gained so much weight, making me sympathetic to the striving of stones. Don’t know when it happened, exactly—maybe as years of voluntary confinement accreted, hardening to sheer captivity.

***

Earth Day, April 22, 1992. A breeze lifts the bedroom curtains. Rain-spatter from the eaves whispers. Wind and rain seem to have arrived to comfort me, or maybe, in the way of women and storms, to deliver me. For two days I’ve been feeling the restlessness felt by gravid females of many species about to give birth.

My transformation began in low chemical whispers between cells. Brain and womb talk together, drawing on ancient knowledge they can speak only in doing, so I can’t know what I know—what my female theme, running deeper than dreams, knows. Birth, like the change in seasons, is a rough chart at best. We may have hours, even days, of waiting.

As contractions intensify, I leave Mark and my two-year-old son Saul sleeping in bed, arrange pillows on the living room couch, and lean back. In my mind, I walk into the oceanic pulses. Waves start small, then heave higher until one rises above my head. Here comes the big one. Let it come—Ai! I parcel out breaths. The wave crashes down, tearing away air. Diving into it, I feel its muscle crush, can almost taste the salt. It passes. The ocean rocks back in beauty. Look out on the expanse. Rest, till the next swell.

Thus I weather the power bearing me away from civilization into the wilderness of body. I’ve lived in this body for decades, yet there remain un bridled tracts, like this one.

Things pick up. I wake my husband. “We’re close,” I say. Lulled into false security from my long hospital labor with Saul, Mark rises slowly and gathers our things at his leisure.

Suddenly, a contraction unlike any of those I’ve felt hits me. It stabs like lighting and totally possesses without consent. I don’t know what it means but understand the situation has become urgent. Gasping, I barely manage to shout, “We have to go—now!” Mark wakes Saul and dresses him. I move onto the bed, where two more contractions rack my body—pulses so intense I hardly want to breathe, but breathing feeds the baby. I flounder between a rational urge to control astonishment and my gut impulse to trust my life and my baby’s life to rogue waves.

After a fourth hard ripple comes a powerful urge to push. Muscles stir, then heave—something inside bursts like an overripe pod. Amniotic fluid soaks into the sheets. Now I know: those four intense ripples were transitional contractions—when the womb’s environment shifts from contractions to open the cervix to contractions to move the baby down the birth canal. The magic girdle tightens. I realize I might give birth right on the bed. “Mark, I’m pushing! Towels!”

He gets them. Moving faster now, he loads the car and helps me to the front door. On the threshold I drop to all fours, overcome by another pusher. Tilting belly earthward, I hang hope on gravity to help me contain this baby a little longer. Saul bursts into tears. As calmly as I can, I tell him I’m all right. The same thing happens in the driveway—hands and knees press the cool, wet concrete.

At the Women’s Center, a nurse helps me onto a bed. Two contractions and five minutes later, I press down my chin, push, and give birth. A nurse exclaims, “It’s a girl! A tiny one!”

A daughter, five pounds thirteen ounces. We name her Mattea: God’s gift.

Somebody asks if she has arrived prematurely. “No,” I say. “Her due date’s tomorrow.”

***

I climb, using my old willow walking stick, a plain tool for gaining leverage in the desert. From time to time, I look back at the moon. It appears translucent: the illusion is that of a sequin reflecting at its edges sur rounding blue broadcloth.

The climb wearies me. But I’m in the desert again and rise to familiar stimuli: sun streaking the canyon’s upper cliff faces; the sequin moon shimmering above red buttes; junipers, the fragrant old folk come into the area millennia ago once the climate became seasoned to their liking.

When I hit the fork leading to Spring Canyon, I hesitate. Can I afford this? Down at the trailhead, somebody pulls in. I want to be alone, don’t want anyone to pass me, stirring up wildlife so it’s gone before I get there. I branch left toward Spring Canyon even though the sign directs me to bear right.

***

There’s something about Mattea—don’t know what. Mark and I call her “our little enigma,” a title we bestowed while she was yet in the womb. When I was pregnant with my son I came to know something about him. We had his name picked out; at birth, he slid right into it.

But this one—even in my arms, even looking into her eyes, I can’t tell who she is. She gives nothing away—not even to me. She fights the breast, biting the nipple and yanking her head sideways as if enraged. Such com bat is the antithesis of that flowing peace I felt nursing my first baby.

She screams all day but sleeps deeply at night. Everyone says, “colic,” but I’m not so sure. She startles repeatedly at the same sound: a snow shovel’s rhythmic scraping against concrete, noises her brother makes in the next room.

There’s something about her eyes. Sometimes they go blank, as if she has retreated to a place beyond my sight. But how do I communicate these concerns?

At Mattea’s two-month pediatric checkup, I say, “She’s not lifting her head.” The doctor holds her in the air above the exam table. It looks like she’s flying. “I can detect no noticeable head lag,” he says. I’m doubtful of the sophistication of such a test but allow his words to cool my worry. His reassurance doesn’t fit, but wanting to believe the best I carry it away.

As the weeks pass, Mattea slips further behind what I have come to expect from raising her brother. At her four-month checkup, I say, “Not only does she not hold up her head, she isn’t using her hands.” The doctor performs the same test as before, lifting her in the air, getting the same results.

“1 just don’t see any head-lag here,” he says. “All babies are different.” He turns to speak with a man outside the exam room about a duck hunt they’ve planned. 1 feel a flash of anger but say nothing. After all, I have a well-paved path of expectations for Mattea; and while I sense that somehow she and I have departed from that path, yet I protect hope.

At Mattea’s six-month checkup, the doctor walks into the exam room, takes one look at her, and says, “Sometimes all a doctor has to go on to know something’s wrong is his instinct.” A mixture of fear and cold irony shoots into my blood. His instinct! I could tell him what I think of his instinct. But now that we’ve got his attention I just want to hear what he has to say.

***

Used to be desert was for me both home and sojourn. In those days no other person or place tugged at my solitude. I was free to offer up everything; often, I did, yet after each stay there was always more to me than when I had arrived. But after seven years’ hard confinement, doubts: nervous little birds flitting in a hedge. I’m hedging.

Maybe I’ll feel alien and unwelcome. Maybe I’ve gone farther already than I ought to have. I think about the risks of hiking deeper into the desert, alone, in my poor physical condition, with only a liter of water. Believing I wouldn’t stay long, I skipped breakfast before coming. Now here I am, embedding myself in the place. But I can’t fight it. The siren song of sand-peppered wind and high canyon walls shifting light works upon desire, calling me in.

I hardly believe it! I’m in the desert again, surrounded by all the old beauties. Old beauties: Just as in me, the desert’s deep themes run like sap in species of plants, animals, and in tones of earth. Designs trade between individuals and run backward and forward through generations. Looking around, I see stories lying exposed in sandstone strata that submerge, then breach again miles from here—at the Grand Canyon or Dead Horse Point—telling the regional tale. Genetic plots and subplots effloresce in tiny blossoms exuding pure confidence.

I press my face into the pale flowers of a cliffrose. A bomb of sweet musk bursts in my nose. Now that I’ve crossed my own reproductive rivers, I recognize it as more than just pretty scent. Shocked, I pull back, but pollen rides away on my nose-tip and upper lip. Perfumed smoke swirls in my nostrils.

“Oh, oh, oh, oh!”

***

The MRI shows that some conflagration has laid waste to more than a third of Mattea’s brain. Water-filled cysts, like giant blisters, remain where portions of right and left lobes once were. Genetic tests come back normal, and close scrutiny of birth records leads to the conclusion that, while the birth was precipitous, nothing about it could have resulted in destruction of such magnitude.

Antibody screening, however, reveals an abnormally high count in Mattea’s bloodstream and in mine for cytomegalovirus. I’ve never heard of it; but as it turns out, it’s a common pathogen, found everywhere—one of the few able to cross the placenta and attack a fetus whose immune system has not yet armed to repel marauders. The reality is staggering: Mattea suffered terrible damage from this organism while in my womb, and I hadn’t a clue. I failed to protect her from something I didn’t even know existed. The doctors’ assertions are severe: “blind and deaf,” “quadriplegic,” “no hope for self-reliance,” “needing a host of interventions.” Some of these I know to be untrue, but the business of sorting through it all to figure out what is or what might be is maddening. Where do we go from here?

***

Deeper into the canyon. Like a tonic, the pollen dispels hesitation. The world rushes through my seven-year fog of diffidence, nearly to the point of overwhelming me, yet my senses, wildly aroused, strive forward.

Ravens’ voices rattle in the cliffs. From time to time, I see a single black bird dip into the wind and sway from rim to rim. Its lazy skimming across a cliff face provokes me.

A canyon wren calls, its song dropping like a pebble down the smooth face of silence. These pebble-notes drop into my soul as if into a pool; ripples of pleasure spread out, then roll back on themselves.

As I walk, a phrase I’ve heard recently leaps to my mind: wilderness interface. This term refers to areas where urban development has crept onto the rough ground of wilderness. Craving relationships with Nature that has receded to areas no longer located near work or shopping, people build among the nearest native wildlife, then commute. Such developments appeal to me, as they do to many others. I mentioned my admiration for one to a friend who works for the U.S. Forest Service.

“A nice area,” she said. “But as a Forest Service employee, I must point out it’s a wilderness interface. The fire hazard is high there and the residents have just one path to safety so far.” She spoke of the fact that the development is thickly wooded, with a single road leading into and out of this tinderbox.

Every year it happens somewhere in the West: wildfire, destroyer of the status quo. Forest, meadow, human flesh, animal flesh, cabin, million-dollar home—it doesn’t matter. Property rights go up in firestorms, resorts and last resorts reduce to ash. Sometimes we fight such fires, trying to save that to which we feel we have a right—home. At other times, it’s just too big. We surrender all, risking to trust the new green sparking beneath ashes of incinerated old growth, new green often dependent, in fact, upon these very fires to prepare the ground for burgeoning.

What I feel as I hike through the canyon is like the chemical and muscular fires of childbirth. It happens not because I will it—though conscious human will leads to points of ignition—but because, I think, the soul has its own wilderness interface area. There the domesticated new brain meshes with the ancient wild one, and sudden fires ignited by lightning bolts of circumstance—vicissitudes—sweep through, burning every thing to the ground. Yet always, lying beneath the obvious and expected, old forms stir, ready to lift life to the next level.

Now I run toward the beauty of this place like a beggar to a table spread with shining delights. But what’s here at hand or within sight isn’t enough. And I don’t desire to devour it, but to get across it.

How can I explain this? At this moment I feel the ground I walk spinning with unnamed and uncounted bodies and forces through wide fields of possibilities. The world I have lived in—a world of senses atrophied by focus upon domestic crises—falls away. Perspective opens. Stretching into blinding blue, I orient by stars I know are there. And there. And there. In the stirring and shifting of lights I taste momentum and position as if on the tongue but can’t taste both at once. It’s heady, like flying. Well, it is flying—life rising to its next level. Yes, I remember now: life craves living. This trip is no longer about escaping captivity. Now it’s about getting out.

***

Instinct. A highly underrated wellspring of genetic—ancient—wisdom. True human instinct is hardly considered, yet it is instinct—not doctors, not medical know-how—that urges me to provide Mattea a point of orientation, a lodestar. Instinctively, I know that lodestar is my body, the ground she grew in. So I keep her by me every minute of every day, wearing her in a baby sling as I go about my daily activities, despite her screaming. I sleep with her pressed against my side or cradled under one arm. Though it’s a hardship, I continue breastfeeding. I don’t go anywhere. I do hardly anything else. It’s all about Mattea, about persuading the relevant gods to release her from that underworld she has been born into.

Also, I find a gifted physical therapist, Dave. He comes to the house and does her more good in two weeks than nine months of visits to doc tors and neurologists. Using simple tools found at hand—a towel, a pillow—he teaches me how to arouse, channel, and then build upon reflexive behaviors whose triggers lie in the old brain, where the remnants of Mattea’s deep themes lie buried.

At Mattea’s yearly pediatric checkup, a nurse measures her head circumference. I look at the graph: her cranial growth curve is flattening out. Besides damaging the larger lobes, the virus attacked her brain stem where brain growth cells generate. The doctor says to expect that one result of Mattea’s brain injury will be microcephaly, or abnormal smallness of the head. He explains she’ll be severely developmentally delayed—what some call retarded.

“There is a direct relationship between head size and intelligence,” he tells me. At home, I measure my head and Mark’s head with a tape measure. “I’m two and a half centimeters more intelligent than you,” I announce to him.

Dave tells me some CMV babies are indeed intellectually impaired. They progress, but only by behavior modification. “But I see a growing richness of response in Mattea,” I say. “She has inflection in her voice, which shows capacity for language.”

“Yes, but there are other indications.” Dave explains that the games he’s seen us play—”where’s the kitty?” and “hit the balloon”—demonstrate cognizance. Mattea shows signs of being intellectually able, but her intellectual development is inhibited by her extreme physical challenges. He says, “I have a lot of optimism for Mattea’s future. In the last six months I’ve been visiting her regularly, she has literally come alive. She’s getting out,” he says.

One day as Mattea lies on the floor banging her left arm and fist against the carpet, I crumple a piece of paper and place it within reach. Startled at first, she investigates the paper cautiously with the back of her hand, keeping her palm locked up tight inside her fist—a reflexive behavior common to brain-injury sufferers. When she knocks the paper out of reach, she complains loudly. I replace it. She smiles her contentment.

That smile! Doctors look at me doubtfully when I tell them she smiles. They don’t think she’s capable of it—they don’t think she’s capable of anything. When she’s with them, she withdraws into her cave or screams because of rough handling. The neurologist asks, “Does she scream like this all the time?” Mark and I look at each other. Our thoughts are one: Not anymore, not with us.

Every day has been spent groping along the sloping walls of her daily experiences, trying to find that place where she goes. It’s a strange region I have no chart for. Society hasn’t developed sufficiently to feel motivated to map the neural anarchy of the injured brain. At least, not to the point where the knowledge and technology filter down to common folk with usual doctors and modest insurance plans.

In the way of unextraordinary doctors, ours speak in terms of conformity, not retrieval or recovery. What means they have to help her achieve an appearance of normalcy—drugs and surgical interventions laced with risk—they’ll impose. Some procedures offer hope but others are obviously more about how she looks rather than who she is. So in my quest to rescue her, I have only old relations to draw upon, the bottomless desire of mother for child. It’s all part of a map in the blood, one I follow to its edges, where new lines suddenly appear, as if by magic. For years.

As I couldn’t express my early doubts to our pediatrician, it’s hard to speak now of my ecstasy when Mattea makes direct eye contact. Her looking lasts just a split second before she experiences neural overload and has to glance away.

Those eyes flickering off remind me of something. Ah, yes. That sense of unbalance one feels when one looks out on the universe and feels in the soul as if in wings intractable hunger for flight.

***

I return to where the Spring Creek trail meets the Chimney Rock Loop, bear left again, and once more start climbing. Now it’s hot. Bright, too—light is everywhere, bounding and rebounding. The trail is steeper for longer stretches. I have to stop more frequently to catch my breath. My poor legs—they quiver from strain. I truly regret my weight but can’t change it in the next two hours. Just have to work with what’s there.

Finally the light becomes so intense I’m forced to look into my shadow for relief. In Spring Canyon’s sheltered morning I had no shadow. But here, climbing the trail’s eastern incline, my shadow’s edges are clean cut, as if from paper.

I reach the butte’s top, cross it, and begin my descent. My shoes aren’t suited for the steep terrain, and here’s where my walking willow proves useful. A stabilizing influence, it gets me down the trail. Reaching the bottom, I look out of my shadow at the landscape. Everything has changed, everything in my field of view and everything in my soul. At first I think I’ve strayed onto a wrong path, the trees, plants, and stones all appear so differently in the highlight. But no, it’s the same path, just winding now through a different part of the day.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue