Articles/Essays – Volume 01, No. 2

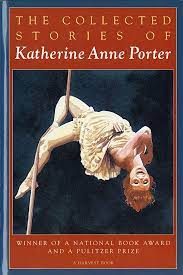

Fools of Life | Katherine Anne Porter, The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter

The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter has been published following the success of her long novel, Ship of Fools. None of the stories is new although she includes three “lost” stories and has finished a fourth from an early manuscript. The resulting volume contains her earliest work, Flowering Judas, the three short novels in Pale Horse, Pale Rider, plus the stories published in The Leaning Tower and Other Stories, all written between 1922 and 1944.

Katherine Anne Porter is acclaimed as one of our most important living writers, not because of the volume of her work, which has been modest, but because of her stylistic accomplishment. She follows the manner of Henry James and Edith Wharton. Like James, Miss Porter focuses each story on a central character through whose eyes the reader gradually discovers the situation and its meaning. Her style is less involuted than James’s, and when she is symbolic, her symbols are large — a landscape, a house, or a train of thought that illuminates the mind of her character. Other writers can learn much from her precise description, her careful structuring of events and conversations, her exact vocabulary, and her exploration of moral issues without moralizing.

Her work should be especially interesting to Mormon readers — and writers — because she comes from a religious background, although her feeling for family and for the traditions of the South and Mexico seems to be stronger than her Catholicism. More than James or Wharton, she celebrates a section of the country and its people. She is a local-color writer turned psychologist and an objective and poetic stylist who does not avoid moral issues. She writes some of her best work about herself and her family, who were Kentucky plantation aristocracy that had moved to Texas, or about her experiences among Mexicans and Germans. But she demonstrates that lands and people can provide source material without limiting an artist’s perspective on personality. For all her careful laying of setting — a farmhouse kitchen, a country lane, a cafe — she never succumbs to mere description. The center remains the thinking, feeling, remembering mind of the character who lives in the setting and reveals a part of his life.

Mormon writers may profit more from studying Miss Porter’s style than from observing her use of religious ideas. While her stories have the morality of individual life as their central concern, she is seldom articulate or resolute about the world view Catholicism should have given her. An absence of positive comment seems to express implicit criticism of the Church. Her characters take from religion only the strength and comfort of tradition, not any personal conviction of truth. Catholicism has little moral influence on the Mexican peasant, Maria Concepcion, knife-swinging wife of an unfaithful husband, whose purpose in life beyond faithful attendance at mass is to kill her rival and win back her man. When Miss Porter confronts moral problems head on, as in “Noon Wine,” she responds to these crises with primitive and suicidal solutions, rather than mature or philosophical ones.

Among Katherine Anne Porter’s more sophisticated characters, interest in social reform for the most part has taken the place of religious allegiance. Laura, the heroine of “Flowering Judas,” is an American school teacher in Mexico who carries messages for the revolutionary underground. From time to time she surreptitiously enters a church to try to pray, but neither her old religion nor the philosophy of revolution satisfies her. When a young political prisoner dies of an overdose of sleeping drugs she has smuggled to him, Laura dreams she is eating the blossoms of the Judas tree as they are transubstantiated into his flesh and blood and awakens in terror. That is the end of the story; the Church provides symbols for guilt but no return route for the lost soul.

In her introduction to the 1940 edition of Flowering Judas, Katherine Anne Porter says that because she found the world sick and society dislocated, her energies have been spent in trying “to understand the logic of this majestic and terrible failure of the life of man in the Western world.” Her writing probes the reasons for failure without offering much hope for change and correction.

Here I must take issue with Miss Porter’s approach to reality. Her people have no sense of purpose to raise them beyond the vortex of their own pasts. Parents and children, friends and lovers, never reach deep personal understanding of each other, with the result that nothing in life means much. No one saying w7hat he believes is understood by another. No purpose — neither art, politics, religion, or love — gives ultimate meaning to life. Only in the death coma of Granny Weatherall in “The Jilting of Granny Wetherall,” or in the feverish delirium of Miranda in “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” comes some epiphany, some visionary reconciliation of past desires with present suffering and future hopes.

Like the young Miranda of “Old Mortality,” Katherine Anne Porter refuses to understand the world in conventional terms. Fleeing distortions, she vows to see life for herself, to find truth through her own experiences. Such a declaration of independence both frees and limits a writer. She is free to create observing, sensitive, analyzing spirits who can study human failure, but she also divorces herself from systems of thought that might lead her characters to positive action or hope.

Only the domineering, horseback-riding grandmother in “The Source” has the moral strength to give meaning to the world around her. The grandmother, once a Southern belle, has become matriarch of a clan and holds together her family, homes, farm, and servants by her will to work and her power of command. Her authority and sense of duty provide security for the whole family. When she dies and the Negro nanny who has been her life-long companion retires, the family begins to disintegrate. A counterpart of this grand dame appears in “Holiday,” where absolute obedience to the mother and father brings stability to a German immigrant farm family. In both these households, feelings of affection are subjugated to the larger interests of work, increase, and solidarity. When individual members separate themselves from the family group, the authority that defined their identity loses its force, and they face the world alone, confused by its injustice, falsehold, and misery.

There, too, Miss Porter’s readers are left without hope; they are philosophically, as she said of herself and the deformed sister in “Holiday,” “equally the fools of life.”

The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1965. 495 pp. $5.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue