Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 1

Forgotten Relief Societies, 1844-67

Nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint women showed a remarkable propensity for organizing. To engage in benevolent service, to share useful information, to fill social and spiritual needs, they met together in the humid summers of Nauvoo, Illinois, and in the blustery winters of Cardston, Canada. Mormon Relief Societies emerged in struggling branches in Europe and in new-founded settlements in Arizona and Wyoming. But between the vigorous movement in Nauvoo and the equally vital organizational efforts which began in the late 1860s fell a twenty-three year gap.

The Female Relief Society of Nauvoo received its initial impulse in 1842 from a seamstress’s proposal to sew shirts for the men working on the Nauvoo Temple. In response, Sarah Kimball and her neighbors organized the effort, which the Prophet Joseph Smith soon sanctioned and amplified, declaring organization for women to be an essential feature of the organization of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Evidence that the Nauvoo Relief Society filled more needs than covering a few backs was the involvement of approximately 1,300 women in its activities.[1] But the original Relief Society was disbanded in early 1844 in the midst of conflicts in southwestern Illinois which threatened to tear the Church apart, conflicts which led to the eventual murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Indeed, Church leaders may well have suspended the Nauvoo Relief Society because of lack of confidence in its president, Emma Smith, wife of the Prophet.[2]

In late 1867 Brigham Young instructed Latter-day Saint bishops to organize Relief Societies in their wards and authorized Eliza R. Snow, secretary of the original Relief Society, to assist. Less than two years later, Latter-day Saint women had created an impressive, far-flung organization which has persisted to the present time. Still, the gap between Nauvoo and the permanent “restoration” of the Relief Society is puzzling. Published accounts tell of the brief existence of local women’s organizations, formed in Utah wards in the 1850s. They included an “Indian Relief Society” which functioned briefly, then expired by mid-1858.[3]

The gap is more apparent than real. Actually, there was a profusion of women’s meetings at Winter Quarters in the spring of 1847 and again in the Salt Lake Valley from the fall of 1847 to the first months of 1848. Small groups of women met in private homes where they encouraged and blessed each other, often exercising such spiritual gifts as speaking in tongues. “Had a rejoicing time thro’ the outpouring of the spirit of God,” was a typical comment in Eliza R. Snow’s journal in April 1847. “All hearts comforted.”[4] Although there was no formal organization, procedures were well defined, and different women presided at various meetings. Eliza Snow and Patty Sessions were prime movers in initiating these meetings. Thus, sagging spirits were bolstered and deep feelings of sisterhood, begun in Nauvoo, took root.

These unofficial “female meetings” tapered off drastically by the spring of 1848, several months after most of the women made the trek across the plains to Utah. Women’s meetings were then held only occasionally for several years. Interestingly, women met most frequently while Brigham Young and other Church officials were traveling, which may suggest that their absence made the need for mutual comfort and encouragement more acute. On the other hand, the women possibly knew or felt that the brethren did not approve of their holding “spiritual feasts” too frequently.[5]

The first formally constituted women’s organization in Utah for which records exist was the Female Council of Health, begun in Salt Lake City in 1851. Its initial nucleus was a group of midwives who had been meeting weekly at the home of Phoebe Angell, the mother of Brigham Young’s wife Mary Ann. They were members of the Council of Health, a local body founded in 1849 which was open to both men and women. Realizing that some women were reluctant to discuss medical matters in the presence of men and thus did not wish to join the Council of Health, the parent council organized the auxiliary female council and expanded it to include any woman interested in health care. Phoebe Angell was appointed its president and treasurer 17 September 1851 with Patty Sessions and Susannah Lippincott Richards as counselors. Members of the Female Council heard lectures by local physicians, discussed the use of faith and herbs in healing, attempted to design more healthful female fashions, spoke and sang in tongues, and enjoyed a social and spiritual interchange. They generally met twice a month. While no figures are available for the member ship or attendance of the group, the fact that they occasionally met at Salt Lake’s old tabernacle would seem to indicate that a considerable number of people was sometimes involved. In November 1852 the Female Council of Health appointed representatives to all but two of the nineteen wards in Salt Lake City to provide for the health needs of the poor. After the death of Phoebe Angell in November 1854, Patty Sessions was appointed to succeed her as president.[6]

Other needs soon arose which were outside the specific concerns of the Female Council of Health, and women responded with another organization. This time Brigham Young and other male Church leaders evidently helped provide the initial inspiration, but not the specific authorization, for the women’s new organization. In the fall of 1853 Utah was limping toward the close of the Walker War, a series of sporadic conflicts with the Ute Indians. President Young began to outline with fervent intensity his vision of the mission which the Latter-day Saints should undertake among the Indian people. Latter-day Saints interpreted the Book of Mormon to find that Indians were descendants of the House of Israel who had been partakers of true religion and an advanced civilization, but had fallen to a degraded state. They were to be redeemed from degeneracy by the “gentiles,” including particularly the Latter-day Saints.[7] Now, in this land of Utes, Paiutes, and Shoshoni, Latter-day Saint colonizers were confronted with the frustrating necessity of coexisting with people whom they were supposed to help but who often resented the Mormon presence and came into conflict with them. Brigham Young focused on the irony of the situation:

My mind is continually upon the stretch and the spirit is upon me all the time and these are my thoughts and meditations, to say what is the use to send missionaries to all the world to convert the world, while we have a tribe of Israel in our midst, which [we] are called upon to save and redeem from their degredation and misery, and make them acquainted with the light and glory of the gospel of their fathers, but instead of this, many have appeared to only wish them dead, this mission is near, when the Lord will require it at the hands of this people, to save this portion of Israel.[8]

In the opinion of President Young, so urgent was the necessity of undertaking missionary work among the Indians that he urged Church leaders in early October 1853: “The time has come. If you will find a man to preside [in Salt Lake City] I will go. I say turn to the House of Israel now.”[9] Two days later he issued a call in general conference to two dozen individuals to serve as missionaries among the Indians in the Great Basin. The Saints, he declared, had been driven from Nauvoo to the West so that they might preach the gospel to the Indians. The missionaries’ first concern should be “to civilize them, teach them to work, and improve their condition by your utmost faith and diligence.”[10] The following week, in an epistle to the Church throughout the world, President Young and his fellow authorities announced: “The time has come for the leaven of salvation to be offered to the remnants [of the House of Israel—the Indians] that dwell on the continent of America.”[11]

Salt Lake City was relatively prosperous that autumn. Utah had experienced four consecutive good harvests. Business was brisk and most stomachs were full. Mormon apostle Parley P. Pratt suggested to the large October conference audience that heretofore, the settlers had been hard pressed just to sustain themselves and promote the immigration of their fellow Saints,

but now we are able to feed and clothe the Indians, or at least, the women and children. They are discouraged at their situation, which is the cause of their stealing; but now the time has come to improve them, and bring about their restoration and redemption, no matter what labor or expense is incurred thereby; for every word of that book [Book of Mormon] will be fulfilled, for it is the word of God unto you, and if we can redeem the children of Nephi and Laman we shall be made rich in the promised blessings.[12]

The Indian missionaries were expected to depart in the spring of 1854, when conditions were more favorable for travel. In the meantime, Pratt’s comments about feeding and clothing the Indians must have fallen on responsive ears. Several women of Salt Lake City, including Matilda Dudley, Mary Hawkins, Amanda Smith, and Mary Bird, met 24 January 1854 and decided to organize “a socity of females for the purpose of makeing clothing for Indian women and children.”[13] Two weeks later, 9 February 1854, at the home of Matilda Dudley, a thirty-five-year-old native of Pennsylvania, they formally organized. Matilda was elected president and treasurer; Mary Hawkins and Mary Bird, counselors; Louisa R. Taylor, secretary; and Amanda Smith, assistant secretary. Twelve other charter members were listed. They adopted four resolutions: Each new member should pay twenty-five cents; meetings were to be opened and closed with prayer; the society was to meet at 9:00 A.M. and close at 4:00 P.M.; and their first effort would be to make a rag carpet, sell it, and use the proceeds to purchase materials to make clothing for Indian women and children.[14]

The women’s work progressed over the next four months. They expanded their membership, met weekly at the homes of various women, and took in donations which included seventy-five cents’ worth of saleratus from Miss Dud ley and varied cash contributions. The hymns they sang reflected the religious and humanitarian nature of their undertaking. One, Parley P. Pratt’s “Oh, Stop and Tell Me, Red Man,” bespoke the hopes for the Indian peoples which the women’s organization embodied:

Before your nation knew us,

Some thousand moons ago,

Our fathers fell in darkness,

And wander’d to and fro.

And long they’ve liv’d by hunting,

Instead of work and arts,

And so our race has dwindled

To idle Indian hearts.

Yet hope within us lingers,

As if the Spirit spoke—

He’ll come for your redemption

And break your Gentile yoke;

And all your captive brothers

From every clime shall come,

And quit their savage customs,

To live with God at home.[15]

With the coming of the spring thaw, 1854, Brigham Young sent the Indian missionaries to the vicinity of John D. Lee’s small settlement at Fort Harmony, Iron County. Then, almost on their heels, he set out himself with a large traveling party to visit settlements south of the Salt Lake Valley, hoping to establish peace with the Utes. His visit with Chief Wakara at Chicken Creek, Juab County, was “eminently successful,” as he expressed it.[16] Wakara and two other chiefs accompanied him for much of the remaining trip, having assured the Mormon leader that even men traveling alone to California need not fear violence from these Native Americans.

Peace with Wakara and establishment of the Southern Indian Mission signaled the beginning of the Mormons’ most ambitious attempts to establish positive relationships with the Indians. By now Brigham Young recognized that enormous cultural differences posed formidible challenges. Still, he expected his people to aid the Indians in a substantial way and, in so doing, to strengthen their own position in the Great Basin. The Indians’ precarious living conditions would improve as they learned skills in homemaking and health care, in raising cattle and growing wheat. Hopefully, many of them would eventually be converted to true religion as a part of their Mormon-sponsored redemption.

For the balance of his southern trip, Brigham Young turned his attention to the relationship he wished the missionaries and Utah’s southernmost settlers to establish with the Indians. At Fillmore and Parowan he challenged the Saints to overcome their aversion to Indians, mingle with them, and teach them. “We have a considerable pill to swallow,” he frankly declared, but now was the time to make good past promises: “I am sure there r [are] women present who have spoken in tongues [prophesying] that they would have to go among the Lamanites & instruct them to sew to knit to wash & perform all domestic works & the men have said that they were going to preach to the Lamanites I ask you now r you going to swallow your faith and eat up your own revelations & persecute these poor degraded beings who are forsaken of God Now I tell you the time has come that you will have to carry out that which you have seen years & years ago & make them honorable.”[17]

The women of Parowan were to play a major role in carrying out President Young’s instructions. An 1855 report of assignments gives a glimpse of skills and spiritual gifts crucial in everyday pioneer life which the women shared with their Indian neighbors: “Tom Whitney, an Indian, was set apart as chief of these Pai-edes [Paiutes], and Aunt Mary Smith, sisters Meeks, West, and Fish were set apart as nurses and teachers to the females, to teach them their organization, the taking care of children, &c, and to nurse according to revelation, that is, by laying on hands, anointing and with mild herbs.”[18] Young’s southernmost stop was at Fort Harmony, where he reiterated to the Indian missionaries that their immediate purpose was to feed, clothe, and teach the Indians, and learn to speak with them in their own language.[19] While the missionaries could help the Indians learn to farm more efficiently and provide them with some food where necessary, there was little they could do to clothe them. On the sound insight that a cultural transformation must include clothing (not to mention the necessity of providing protection against the elements), the missionaries appealed to readers of the Deseret News to donate used clothing, “especially shirts, to help cover the nakedness of the Indians, especially the women.”[20]

Brigham Young went further. He announced to the people of Parowan: “We are going to propose to the sisters when we get home to make clothes, &c for the Indians & I give you the privilege to make clothing for those little children & the women, but the men I dont care so much about.”[21]

Now Parley Pratt’s suggestion of the previous fall was to be implemented: the Mormons would help clothe the Indians — specifically, those in Southern Utah. With this goal in mind, President Young, apparently unaware that an Indian Relief Society was already functioning in Salt Lake City, had a surprise awaiting him when he returned home.

Brigham Young’s first Sunday sermon after his return reflected the optimism generated by his trip south. He declared that the Lord’s spirit was influencing the Lamanites, that they would be converted were it not for “the foolishness of the whites,” and that the time had come for settlers to play a more active role in their behalf. Turning from these generalities, he made a specific proposal which was strikingly reminiscent of Nauvoo and the organization of a Relief Society there: “I propose to the Sisters in this congregation to form themselves into societys to relieve the poor brethren and sustain them. We need not have a poor family. I propose to the women to clothe the Lamanite children and women and cover their nakedness. All the Lamanites will be numbered within this Kingdom in a very few years and they would be as zealous as any other. The sisters should meet in their own wards and it will do them good.”[22] Once again, as in Nauvoo, ecclesiastical leaders had capitalized on a fledgling women’s organization which had been initiated independently to achieve specific goals and sanctioned its expansion to meet official ends.

Brigham Young did not refer to the women’s society which had already been functioning for four months, but by now he must have been conscious of its activities. The Wednesday following his homecoming address, one of his wives, Augusta Cobb, sang at its regularly scheduled meeting. Later that day, at the same location, Matilda Dudley chaired a meeting organizing a separate society for the Salt Lake Thirteenth Ward. She was elected president and treasurer; Augusta Cobb, first counselor; Sarah A. Cook, second counselor; and Martha Jane Coray, secretary. Appropriately, these meetings were held in the home of William and Rebecca Hennefer: William was one of the Southern Indian missionaries.[23]

The initial concern of the local societies, quickly organized in Salt Lake Valley, focused on the Indians, although Brigham Young’s injunction to the women also called for aid to the poor among themselves. After some debate, the Thirteenth Ward organization adopted the name “Female Indian Relief Society.” (Brigham Young’s records used the term “Indian Relief Society.”) Patty Sessions referred to the Sixteenth Ward society, of which she was elected president, as “a benevolent society to clothe the Indian squas [squaws].”[24]

The initial society for Indian relief, consisting of women from several Salt Lake City wards, met once more to finish cutting their carpet rags. They then disbanded and became members of the societies organized in their own wards. Their president, Matilda Dudley, was elected president in the Thirteenth Ward, apparently a confirmation of her being “called to preside” by Bishop Edwin D. Woolley. Amanda Smith of the original society became president of the Twelfth Ward group. Bishops were apparently charged to organize societies in their wards although they seldom participated directly in Indian Relief Society meetings.[25]

At least twenty-two Indian Relief Societies were organized in 1854, primarily in Salt Lake City. There was no systematic effort to encourage organization outside the city; however, a smattering of other wards also founded Indian Relief Societies. South Weber Ward, about twenty-five miles north of Salt Lake City, responded favorably when Phoebe Woodruff visited in June with her husband, Wilford, and encouraged the women there to organize. Other outlying settlements involved in the clothing drive—presumably through organized Relief Societies — were Big Cottonwood (Holladay), South Cotton wood (east of present-day Murray and west of Holladay), West Jordan, and Mill Creek. Interestingly, Brigham Young’s own Eighteenth Ward was one of only three in the city which failed to organize. His wives, Mary Ann Angell Young and Augusta Cobb, and his daughter-in-law, Mary Ann Ayres Young, were all active in the Thirteenth Ward’s society.[26]

The Indian Relief Societies met biweekly, weekly, or occasionally oftener when the women were eager to complete Indian clothing for a shipment south. The societies seemed somewhat ad hoc, working diligently on a short-term project of some urgency, yet reflecting concerns beyond simple relief programs. Soberly, the Thirteenth Ward women entered into a covenant: “That we speak no evil of each other nor of the authorities of the Church but endeavor by means in our power to cultivate a spirit of union humanity and love and that this shall be the covenant into which all shall enter who become members of this society.”[27] This covenant was a tacit admission that disunity and gossip were viewed as potential problems, perhaps indicating that the society consciously sought to avoid some of the problems of the Relief Society at Nauvoo.

One of the first activities for the Relief Societies was soliciting donations. The Thirteenth Ward approached this task systematically, assigning pairs of women to visit specific blocks within the ward territory and request contributions. They accepted cash, yardage, sundry sewing items, carpet rags, and various items which could be converted into cash. Occasionally, a used article of clothing was donated. The Society sponsored a party in the Social Hall and the proceeds were used for Indian clothing.[28]

Having received donations, the women proceeded with the first phases of production. The Twelfth Ward bought one and one-half bolts of sheeting and began to sew clothing from that material. They also bought cotton, dyed it, wove it into thirty-three yards of plaid, then proceeded to make clothing items from it. Other materials used included linsey, homespun gingham, “Jeans,” hickory, calico, linen, “factory,” and “drilling.”[29]

Dresses were the most numerous items sewed. Also common were slips, chemises, sacks (short, loose-fitting coats), and shirts, with an occasional apron, pair of stockings, or handkerchief. One sister donated a used purple woollen petticoat. Indian Relief Societies also made several quilts and, occasionally, blankets.

Individual ward Indian Relief Societies delivered the Indian clothing they had produced to Brigham Young, presumably by taking it to the General Tithing Office on the corner of South Temple and Main in downtown Salt Lake City, where clerks recorded in detail what was received. Brigham Young’s twelve-year-old daughter Luna, daughter of Mary Ann Angell Young, thus delivered one lot of children’s clothing from the Thirteenth Ward.[30]

[Editor’s Note: For the list, see PDF below, p. 114.

Even more detail was given for a shipment from the Sixteenth Ward:[31]

[Editor’s Note: For the list, see PDF below, p. 114]

Each Relief Society was credited separately on Brigham Young’s financial records for all items brought in. The bulk of Indian clothing was produced in a four-month period, from June to September 1854, although several items came in as late as December. The last items, two dresses, were contributed in April 1855. In all, Indian Relief Societies contributed Indian clothing and bedding valued at $1,540 and cash totaling $44. In addition, seventy-eight yards of rag carpet valued at $90.50 were credited to the Twelfth and Fourteenth Ward Indian Relief Societies and were purchased by Brigham Young’s household, probably for use in the newly completed Lion House. The proceeds may have been used to purchase materials for Indian clothing.[32]

The average Indian Relief Society produced $70 worth of Indian goods representing about fifty items of clothing and bedding. At the same time, the five most productive wards contributed an average of $182 in goods, amounting to about 90 items from each ward. In all, the Indian Relief Societies contributed nearly 900 items of clothing, most of which were sewn specifically for the Indians by the women themselves. Given the fact that work was done by hand and that the communities contributing these items had a total population of less than ten thousand in 1854, the productivity of these women was impressive. In the Thirteenth Ward at the peak of activity, each of forty-one women donated an average of almost one day per week to this work; and the Twelfth Ward involved as many as twenty-one women in one work session. However, after the burst of initial enthusiasm in which much of the Indian clothing was completed, a typical work meeting would draw fewer women.[33]

Between August and October, Brigham Young shipped Indian goods valued at $1,880 to Cedar City for distribution to the Indians by Iron County settlers, and to Harmony for the Indian missionaries to distribute. This included some items purchased from or contributed by Salt Lake City merchants, as well as Relief Society donations. Isaac C. Haight, Cedar City mayor and iron works superintendent, and Rufus Allen, head of the Southern Indian Mission, were instructed to keep detailed accounts of their disbursements. The clothing was not to be a “handout”; rather, it was to be used to teach Indian families to work for goods they desired. Settlers and missionaries were to distribute the clothing to Indians in exchange for labor, or for skins or other items. In turn, they were to return payment for the clothing to Brigham Young, who represented the Church. Considering the barter economy of these remote areas, the Church’s credit system provided a fairly convenient means by which all these transactions could be handled.[34]

Some modification of Brigham Young’s instructions was necessary. Haight found numerous articles of clothing “all together unfit for the Indians,” and was allowed to sell them to settlers, many of whom had received insufficient supplies that year. He was also allowed to use his own best judgment in setting prices after he complained that the listed prices were too high. Allen was per mitted to give away items of clothing to Indians when, in his opinion, circumstances warranted it. The point was that the Indian goods were a means to an end, not merely a commodity for sale.[35]

The generous donations made by the women of Salt Lake City saturated the market for Indian clothing in Southern Utah for years to come. Initial distribution was quite modest. During the first two months, Haight’s books accounted for sales of $235 to settlers for distribution to Indians, theoretically leaving $466 in goods on hand.[36] The settlers of Cedar City did not work with as many Indians as some had expected. In November David Lewis, first counselor of the Southern Indian Mission, counseled them that they should not leave all the necessary work with the Indian people to the missionaries. He urged: “I would advise that you employ them — feed them well and at the end of a week or so give them one of those shirts which the Sisters of the various wards in and around the city [Salt Lake City] made & [which are] now lying among you to warm them [and] cheer them on to future diligence. These with out your employing them may lie on the shelves & the Indian remain cold.”[37]

But the missionaries fared little better. They reported that soon after the arrival of the Indian goods, “from a little misunderstanding of instructions and other motives,” a few items had been used by white men and their families. They promised this would not happen again. After two months they had sold little clothing to Indians. Since their own crops failed that fall, they turned to haying at Cedar and Parowan to sustain themselves and had to recommend to the few Indians they met to seek employment in the towns. While the Indians who did so soon became sufficiently clothed, others preferred to live in the deserts and canyons where they hunted rabbits and other small game for food.[38]

With the expansion of the Southern Indian Mission southwest to Santa Clara, new opportunities arose through the willingness of Tutsagavits and other Paiutes to cooperate with the missionaries, to help them build homes, and to learn the arts of settled agriculture. By May 1855 Jacob Hamblin had distributed nearly $50 in Indian goods at Santa Clara. Others who bought clothing for Indians that spring included John D. Lee, Charles W. Dalton, and Robert Ritchie of Harmony. Items were generally sold for one-third to three-fifths of the original list price. Distribution at Harmony and Santa Clara continued at least as late as October 1855.[39]

By May 1856, some Indian relief goods remained at Cedar City and at Santa Clara, but their distribution no longer conformed with Brigham Young’s original instructions. With the Southern Paiute market saturated, the supply was apparently drawn upon for the purchasing of Indian children from the Utes and for trading for skins. Indian missionaries and settlers occasionally purchased Paiute children from the Utes, preferring to bring them them up in Latter-day Saint homes rather than see them abused or taken to Mexico for sale as slaves.[40]

Latter-day Saint settlers found the Southern Paiutes, to whom most of the clothing was distributed, more inclined to cooperate and more willing to learn from the Mormons than were their neighbors, the Utes. The Utes frequently received gifts but apparently did not regularly earn clothing for steady work.

What effect the Indian Relief Society movement had on the Indians of Southern Utah is impossible to assess with any confidence. As a tangible sign of Mormon goodwill, providing clothing and bedding in return for labor or commodities helped alleviate antagonism and promote friendly relations between the Southern Paiutes and the Latter-day Saints. It may have enhanced the respect and friendship which Mormons such as Jacob Hamblin received from many of these Indians in the initial months of their relationship. And there were some real attempts by Southern Paiutes to adopt the ways of Mormon farmers.[41]

Nevertheless, relatively few Indians actually worked with or for the Mor mons over extended periods of time. Among the starving Paiutes, as well as the Utes and Shoshoni, there was a growing inclination to seek handouts from Mormon settlers, rather than adopting their ways. Southern Paiutes who did try to fit into Mormon society often suffered culture shock. Few adult Indians were effectively converted to Mormonism. Few male Indians who grew up in Mormon homes married and raised families. Adult Indians and the children of mixed marriages suffered socially in Mormon communities. The excitement surrounding the Mountain Meadows Massacre in the 1850s, the Black Hawk War and Navajo wars of the 1860s, and the creation of reservations disrupted or changed the character of Mormon-Indian relations. The Indian population declined, partly because of epidemics; and aid to the Indians was increasingly left in the hands of the federal government. To some extent the Indians were more effectively “controlled,” particularly by the federal government, but they were not “redeemed” in the way Brigham Young had hoped.[42]

In the long run, the Latter-day Saint people themselves were the main benefactors from the establishment of Indian Relief Societies. By December 1854 the associations had produced an ample surplus of clothing for Southern Utah’s Indians. Yet some of the women were reluctant to disband “their” organization. As sewing for the Indians tapered off, women began quilting and making rag rugs for local poor. Soon Brigham Young and the ward bishops, recognizing the potential in the women’s organizations, found other projects for them. In early December 1854, Brigham Young requested the wards of Salt Lake City to provide rag carpeting for the floor of the old Salt Lake Tabernacle. Each ward was to furnish specified lengths and widths for a total of 771 square yards. For an organization like the Sixteenth Ward’s Relief Society, or “Benevolent Society,” the carpeting assignment posed little challenge. They completed half of their carpet by mid-December and soon were ready for other assignments.[43]

Next came a transition to more permanent concerns. In January 1855 Brigham Young notified bishops that he wanted the women to concentrate on aiding the Latter-day Saint poor. Bishop Shadrach Roundy of the Sixteenth Ward told his “Benevolent Society” president, Patty Sessions, that President Young “said we had clothed the squaws and children firstrate; we now must look after the poor in each ward.”[44] President Young had mentioned this facet of relief work in his initial revival of the women’s societies in June 1854, but it had been almost totally eclipsed by special projects.

The transition came in a variety of ways. Bishop Roundy called a special meeting of the existing Sixteenth Ward Benevolent Society to explain the new direction its members were being asked to take. The Thirteenth Ward’s society completed its rag carpet assignment in January but did not meet again until August, when they, too, began to focus their efforts on the poor. They retained the same slate of officers and treated the organization as a continuation of their Indian Relief Society. Perhaps some wards saw the Indian Relief Society as a one-time effort having little or no direct continuity with the new Relief Society. Furthermore, wards and communities which had not produced goods for Indians now created Relief Societies, too. Brigham Young’s announced intention was that Relief Societies be organized in all Mormon wards or communities.[45] By 1858, Relief Societies functioned in Cedar City, Manti, Provo, Spanish Fork, and Willard, as well as in Salt Lake Valley. Clearly, the pattern became widespread, although few contemporary records have survived to fully document the movement.[46]

The need for Relief Society aid to the poor was soon far greater than anyone could have anticipated. In early 1855, the Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake Valley were relatively prosperous and comfortable; but during the summer, grasshopper infestation and drought decimated the year’s harvest, and a severe winter followed. A second grasshopper infestation made the harvest of 1856 no better.[47] With the entire Utah Mormon community on the verge of starvation, Relief Societies had ample opportunity to serve. They took up collections for food, clothing, and money and produced various useful items, especially quilts and rag carpets, which could be provided for the poor, or sold or ex changed for necessary commodities.

Special needs arose so frequently that they became a regular facet of the societies’ activity. Lucy Meserve Smith, president of the Relief Society for the city of Provo, told of providing clothing and bedding for the destitute survivors of handcart treks in late 1856:

I never took more satisfaction and I might say pleasure in any labour I ever performed in my life, such a unimity [unanimity] of feeling prevailed. I only had to go into a store and make my wants known, if it was cloth it was measured off without charge. My councilors and I wallowed through the snow until our clothes were wet a foot high to get things together give our noticeses &c. We peaced blocks carded bats quilted and got together I think 27 Quilts, besides a great amount of other clothing, in one winter for the needy.[48]

In 1857-1858, when United States troops approached Salt Lake City in connection with the so-called Utah War, the Provo Relief Society contributed bedding and warm clothing for the Utah men standing guard in the mountains. They later made a flag for the Provo Brass Band and rag carpets for a new meetinghouse.

The Salt Lake Fourteenth Ward Relief Society made similar contributions. From September 1856 to March 1858 they provided food, clothing, and cash amounting to the following:[49]

[Editor’s Note: For list, see PDF below, p. 120]

Such substantial contributions were significant in a time of deprivation.

Besides helping the poor, one outlying Relief Society broadened its focus to fill other needs. Local priesthood leaders Isaac C. Haight and John M. Higbee blessed the presidency of Cedar City’s Relief Society “with power to wash and anoint the sick, and of laying on of hands.”[50] And Bishop Phillip K. Smith told Cedar City women their organization was “not so much for the supplying of the poor, as for the advancement of the Sisters in the Kingdom of God.”[51] With a charter membership of ninety-five in November 1856, the society quickly became a significant factor in the spiritual life of the community. The Indian Relief Societies were among the first of a variety of organizations which blossomed forth in Salt Lake Valley in the mid-1850s. Within several months, the Polysophical Society, the Universal Scientific Society, the Deseret Philharmonic Society, the Horticultural Society, the Deseret Theological Institute, and the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society all held forth. A spirit of optimism, a broadening of interests, the pursuit of knowledge and excellence in varied fields seemed the order of the day. But during the Mormon Reformation of 1856-57, pluralism was discouraged, and many such organizations declined. Doubtless, crop failures and the progress of coloniza tion dampened the enthusiasm of some groups. The Relief Societies and the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society, organizations of obvious utility, survived.

Latter-day Saint wards in Northern Utah suffered a major organizational setback from the mass evacuation of Saints in the spring of 1858. This move south had been proposed as a means of avoiding encounters with the Utah Expedition, which moved into the Salt Lake Valley in June and eventually established Camp Floyd in Cedar Valley, forty miles to the southwest. When people returned to their homes beginning in July, organizations did not quickly return to their previous state. Relief Societies, having just reached a high point in dedication and effectiveness, thus ceased to exist as a general rule, even in settlements like Provo which had not been evacuated but had been disrupted. It was as if there were an unspoken moratorium on creating local organizations.

The fact that Relief Societies were not then formally reestablished as a vehicle for poor relief and for women’s social and spiritual enrichment may have been due, at least in part, to the multiplicity of voluntary cultural, theological, and intellectual organizations prior to the move south. Some of these societies had aroused apprehension, and the Polysophical Society, in particular, came under open attack by some Church leaders.[52]

Also, the troublesome presence of federal troops and camp followers in Northern Utah apparently had a dampening effect on organized Mormon activities. In January 1859 Isaac Morley told the Saints of Manti, where a Relief Society had continued to function, that they enjoyed the “privilege of meeting to worship while other settlements had not such privileges.”[53] Fear, defensiveness, and demoralization — if not martial law — probably helped curtail group activity at this time.

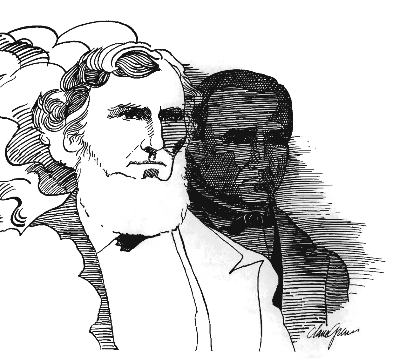

Another issue was male leaders’ perceptions of women’s organizations which affected their relationships with the Relief Societies. In Nauvoo, after Church authorities allowed the Relief Society to grow, Emma Smith’s resistance to plural marriage in that forum aroused doubts about the merits of the organization. Its meetings stopped abruptly in 1844. After Joseph Smith’s death, Brigham Young, president of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, denounced any attempts of Latter-day Saint women to “meddle in the affairs of the kingdom of God.”[54] Accusing such “meddling” of contributing to the martyrdom, he firmly announced that he would take the initiative on reestablishing any Relief Societies: “When I want Sisters or the Wives of the members of the church to get up Relief Society I will summon them to my aid but until that time let them stay at home and if you see Females huddling together veto the concern . . .”[55]

In the mid-1850s, when the Thirteenth Ward Indian Relief Society was formed, someone suggested it be called the “Female Indian Relief Society.” Martha Jane Coray, according to the minutes, “objected to the word Female as no Association could be virtually sustained by females but must of necessity be kept by their Husbands Fathers or Guardians.”[56] Matilda Dudley did not oppose that argument. Rather, she countered that “the labor required was female labor” and that the proposed name was therefore appropriate. Despite such caution, that organization acted more independently than seemed prudent in later years. Bishop Woolley took his time reorganizing the Thirteenth Ward Relief Society, waiting until 1868. Then he pointedly emphasized that the sisters must be subject to his authority.[57]

On the other hand, the Cedar City Relief Society was particularly responsive to the direction of local male Church leaders, at whose urging the society helped promote obedience of wives to husbands and acceptance of the principle of plural marriage. Its visiting teachers sounded out individual women’s opinions on those two topics and reported any dissent they found. Those who persisted in opposing the accepted teachings were to be excluded from the society. In its reinforcement of prevailing community values, Cedar City’s Relief Society partook of the crisis mentality which led to the tragic Mountain Meadows Massacre. Members were exhorted to “mind your own business, and ask no Questions”[58] when their menfolk were called out to fulfill duties. The day before the massacre, the women were encouraged to “teach their sons and daughters the principles of righteousness, and to implant a desire on their hearts to avenge the blood of the Prophets.”[59]

During the decade 1858—67 there were still poor to be cared for, including thousands of immigrants from Europe. Other needs continued to exist which Relief Societies had helped meet, but very few societies were reorganized. Cedar City’s Relief Society functioned until April 1859, then lapsed for nine years. The Manti Relief Society continued at least through 1859, perhaps beyond then. The Spanish Fork Relief Society contributed an ox to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund in the winter of 1860-61 and may have been the only society to have had continuous existence throughout the 1860s. By 1864 Wil lard’s society and perhaps those in a few other locations had regrouped after a period of inactivity.[60]

What accounts for the hiatus? The Latter-day Saints had not lost creative vitality. The construction and establishment of the Salt Lake Theater in 1861-62 and the building of the Salt Lake Tabernacle beginning in 1863 were evidence of that. Nor had they lost the will to provide time and means for the benefit of the poor. There were considerable donations to the Perpetual Emi grating Fund. Hundreds of wagons were sent to the Missouri Valley, and later to meet the railroad as it pushed west, to bring poor immigrants to the Salt Lake Valley. But for reasons that remain unclear, Brigham Young did not explicitly encourage the reinstatement of Relief Societies between 1858 and 1867. Not until after the Civil War, news of the coming of the transcontinental railroad, the discovery of precious metals in the hills of Utah, and the first signs of a major influx of non-Mormons into Utah did any thoroughgoing organizational efforts take place. And until Brigham Young took the initiative, the women were not formally organized into a Church-wide structure.

Uncertainty surrounds the role of Eliza R. Snow, who would later help organize Relief Societies throughout the Church. In what little she wrote or said about Relief Societies of the 1850s, she maintained one point — there was a widespread effort to organize societies beginning in 1855. She might have referred either to the Indian Relief Societies or to the organizational effort which immediately followed. Sister Snow considered the 1855 efforts as the beginning of what eventually became the Church-wide Relief Society under her own leadership. In her mind it was no mere temporary effort. But her own role in 1855 or at any point before 1867 remains less clear. In an 1855 account she seemed to telescope the events of 1855—57 with those of 1867—69, claiming she was commissioned by Brigham Young to promote the organizing effort of 1855. However, there is no evidence beyond her own statement that she played any role except that of encouraging her own Salt Lake City Eighteenth Ward.[61]

Eliza Snow’s poor health — she was reportedly “in the last steps of consumption” in 1848-58—has been mentioned as one reason why the Relief Society was not reorganized before 1867.[62] But her health had improved by the period of least activity, 1859–66, and even during her decade of illness, Eliza was not bedfast. During the time Indian Relief Societies were functioning, she visited friends and was a leading participant in the Polysophical Society. However, she apparently played no role in Indian Relief Societies and obviously was not essential to their success.[63] Other women who led out in organizing and conducting Relief Societies in the 1850s, at least in their own wards, would have been capable of doing so on the same basis in the early 1860s, had President Young given similar encouragement.

The questions about Eliza Snow’s inactivity between the profusion of meetings in 1847 and the whirlwind tours beginning in 1868 parallel our ignorance of Latter-day Saint attitudes toward women’s organizations during the same period. The relative success of the little-known Indian Relief Society movement, the health of its successor Relief Societies of 1855-58 and the overwhelming support given the Relief Society’s reorganization in 1867-69 makes the inactivity of 1859-66 and the relative lack of women’s meetings from 1848 to 1853 appear to be a curious anomaly. Additional insights into the Latter-day Saints’ underlying assumptions about local organization, about women, and about women’s proper sphere of activity are required to satisfactorily explain the events of 1847-67.

The scope of Relief Societies’ activities in the 1850s was usually rather limited, focusing on specific work to be performed. Speaking in tongues, prophesying, and other intensely spiritual experiences characterized Mormon women’s meetings in 1847, the Female Council of Health in the early 1850s, and to some extent the Polysophical Society in the mid-1850s. This was apparently not a feature of the new Relief Society movement, which steered clear of anything that might smack of “meddling in the affairs of the kingdom of God.” The Cedar City Relief Society, with its early encouragement of spiritual gifts, was one notable exception.[64]

In 1867, when President Young asked Sister Snow to supervise the organization of Relief Societies in all wards and settlements, he clearly intended to revive the organization on a broader basis than the societies of the 1850s. Sister Snow’s vision of Relief Society included spiritual dimensions in addition to compassionate service. With her organizational ability, her broader vision of the potential of women’s organizations, and her ability to proceed aggressively while retaining priesthood sanction, Eliza Snow helped establish societies that caught the enthusiasm and filled the needs of their members.

Despite the lack of continuity, the Indian Relief Societies and the Relief Societies which immediately succeeded them in 1855-58 did leave a legacy for Mormonism. Not only did they provide for pressing needs of the time, but they helped establish some precedents. Once established, the tradition of quilting at meetings persisted and has even been introduced outside America in societies where quilting was not common. Beyond that, the notion that some of women’s time at Relief Society meetings ought to be spent “making something” has generally continued until modern times. The monthly “work day” was only recently replaced by a “homemaking day” in which the members receive instruction in homemaking skills. Finally, although recent LDS social and educational programs for Indians have not involved Relief Societies directly, those Native Americans living in each ward are the recipients of compassionate concern and service in the same way as any other member of the congregation.

The Relief Societies of the 1850s, like other facets of Latter-day Saint life in that period, passed rather quickly into obscurity. Yet the vitality of Mormon group activity before the move south—particularly among women—was a significant feature of the pioneering experience.

[1] Jill C. Mulvay, “The Liberal Shall Be Blessed: Sarah M. Kimball,” Utah Historical Quarterly 44 (1976): 210-11. History of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: The General Board of Relief Society, 1966), pp. 18-25.

[2] There is some evidence that Emma Smith used the Relief Society to promote opposition to her husband’s teachings about plural marriage. See Minutes of General [Women’s] Meet ing, 17 July 1880, in “R. S. Reports,” Woman’s Exponent 9 (1 September 1880): 53-54; and Valeen Tippetts Avery, “Emma, Joseph, and the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo: Un suspected Arena for a Power Struggle,” paper presented at Mormon History Association annual meeting, Rexburg, Idaho, 2 May 1981.

[3] Generally, secondary sources recognize the existence of Relief Societies in Utah before 1867 but are vague about their origin and the scope of the movement. The phenomenon of a decentralized but officially mandated auxiliary organization has posed challenges for histories, particularly since the early records were not systematically submitted to Church headquarters. Susa Young Gates, “Relief Society Beginnings in Utah,” Relief Society Magazine 9 (Spring 1922) : 184-96, is the most detailed listing of pre-1867 Relief Societies in Utah. It mentions the Indian Relief Society but defers discussion of it to a subsequent article which never appeared. Emmeline B. Wells, “History of the Relief Society,” Woman’s Exponent 32 (July 1903) : 6-7, evidently had access only to recollections and to Salt Lake City Fourteenth Ward Relief Society records, which later disappeared. Wells may be inaccurate in claiming that “temporary” Relief Societies were organized as early as 1851-52, but she correctly notes that in 1855 Brigham Young directed that each ward should have a Relief Society. The abbreviated treatment in the official History of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: The General Board of the Relief Society, 1966), pp. 28-29 is based on the two above-mentioned accounts. Kate B. Carter, ed., “The Relief Society,” Our Pioneer Heritage 14 (1971): 71-73, 75-78, 103, 113, uses records relating to four supposed Relief Society organizations in Utah before 1867 — records not available to the general researcher — and the Wells article cited above. Eliza R. Snow’s brief mention of the early history of Relief Society, part of an autobiographical sketch prepared for Hubert Howe Bancroft in 1885, is published in Eliza R. Snow, An Immortal: Selected Writings of Eliza R. Snow (Salt Lake City: Nicholas G. Morgan, Sr., Foundation, 1957), pp. 1-48. This account fails to mention either the Indian Relief Society movement or the disorganization due to the move south, and it apparently telescopes events of 1855 and 1867-68. Leonard J. Arrington, From Quaker to Latter-day Saint: Bishop Edwin D. Woolley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), pp. 337-55, discusses the Salt Lake City Thirteenth Ward Indian Relief Society in some detail. Finally, Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), pp. 149-50, drawing in part upon early research for this essay, briefly discuss Indian Relief Societies as a general phenomenon.

[4] “Pioneer Diary of Eliza R. Snow,” 26 April 1847, in Eliza R. Snow, An Immortal, p. 322. See also entries for 14 March 1847 through 6 April 1848, ibid., pp. 320-64; Patty Bartlett Sessions (Parry), Diary, 4 Feb. 1847-26 April 1848, Historical Department Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, hereafter cited as LDS Church Archives.

[5] “Pioneer Diary of Eliza R. Snow,” especially entry for 4 Feb. 1848, pp. 361-62. Father John Smith, who presided in Salt Lake City in the absence of Brigham Young, met with the women 27 Dec. 1847 and they explained “the order of our meetings” to him, ibid., 27 Dec. 1847, p. 360. He apparently approved and promised to meet with them again. Men occasionally presided, but the meetings were organized by women; see Patty Sessions, Diary, particularly entry for 6 Feb. 1849.

[6] Phinehas Richards, Journal, 6 May-20 Dec. 1851, microfilm copy of holograph, LDS Church Archives; Patty Sessions, Diary, 22 March 1851-16 Jan. 1855; Female Council of Health in the Tabernacle, Minutes, 14 Aug. 1852, Miscellaneous Minutes Collection, LDS Church Archives; Christine Croft Waters, “Pioneering Physicians in Utah, 1847-1900” (M.A. thesis, University of Utah, 1976), pp. 14-17, discusses the Council of Health and mentions the Female Council.

[7] See, for example, in the Book of Mormon: 1 Ne. 15:13-18; 22:3-8; 2 Ne. 30:3-6; 3 Nephi 21; Morm. 5:12-21; and D&C 3:16-30; 28:8; 32; 50:24.

[8] Brigham Young Speech, Nephi, Utah, 10 May 1854, Thomas Bullock Minutes Collection, LDS Church Archives.

[9] Minutes of Meeting in President’s Office, 4 Oct. 1853, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[10] Synopsis of Brigham Young’s address, 9 Oct. 1853, Salt Lake City Deseret News, 24 Nov. 1853.

[11] Deseret News, 15 Oct. 1853.

[12] Minutes of General Conference Address, 9 Oct. 1853, Deseret News, 15 Oct. 1853.

[13] “Record of the Female Relief Society Organized on the 9th of Feby in the City of Great Salt Lake 1854,” Louisa R. Taylor Papers, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, cited hereafter as Taylor Minutes. An almost identical record is found in the papers of Amanda Barnes Smith, Church Archives, referred to hereafter as Smith Minutes.

[14] Except for Amanda Smith, survivor of the Haun’s Mill Massacre in Missouri and a member of the Relief Society in Nauvoo, none of the founders of the first Indian Relief Society appears to have been particularly prominent in the Latter-day Saint community. Matilda Dudley was born in Pennsylvania 15 March 1818, became a plural wife of Joseph Busby 13 March 1856, and died in Salt Lake City 8 Oct. 1895.

[15] Sacred Hymns and Spiritual Songs for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 10th European ed. (Liverpool: Published for Orson Pratt by S. W. Richards, 1854), no. 283.

[16] Brigham Young to Thomas L. Kane, 29 June 1854, Brigham Young Letterbook 1, pp. 570-72, LDS Church Archives. Minutes of Meeting, 11 May 1854, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[17] Minutes of Meeting, Parowan, 21 May 1854, Thomas Bullock Minutes Collection, LDS Church Archives. See also Brigham Young Sermon, Fillmore, 14 May 1854, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[18] J. H. M[artineau] to G. A. Smith, Parowan, 30 May 1855, Deseret News, 11 July 1855. The commission to “teach them their organization” may have referred to Relief Society, if such an organization had been established at Parowan by May 1855 as part of the broader movement described below. Or it could refer to procedures normally followed by Latter-day Saints pioneer women in blessing meetings or in washing and anointing expectant mothers and the sick.

[19] Report of Brigham Young Speech, 19 May 1854, Juanita Brooks, ed., Journal of the Southern Indian Mission: Diary of Thomas D. Brown (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1972), pp. 29-31.

[20] Letter of mission scribe, Thomas D. Brown, Deseret News, 22 June 1854.

[21] Minutes of Parowan Meeting, 21 May 1854, Thomas Bullock Minutes Collection, LDS Church Archives.

[22] Minutes of Meeting, Salt Lake City, 4 June 1854, Thomas Bullock Minutes Collection, LDS Church Archives. The minutes are partially in Pittman shorthand.

[23] Taylor Minutes, 7 June 1854; Salt Lake Thirteenth Ward Indian Relief Society Min utes, 1854-57, LDS Church Archives.

[24] Thirteenth Ward Indian Relief Society Minutes, [7 June 1854]; Brigham Young Financial Records: Ledgers, 1853-55, pp. 397-402, and 1854-59, pp. 289-96; Journal, 1853-54, Brigham Young Papers; Patty Sessions, Diary, 10 June 1854; LDS Church Archives.

[25] Taylor Minutes, 13 Jun e 1854; Thirteenth War d Indian Relief Society Minutes, [7 Jun e 1854]; Smith Minutes, 10 June and [13 June] 1854. Amanda Smith’s record thus includes minutes of the Twelfth Ward Indian Relief Society, 10 June 1854-16 Aug. 1854, as well as minutes of the original Indian Relief Society, 24 Jan. 1854-13 June 1854.

[26] Brigham Young Ledgers, 1853-55, pp. 397-402, and 1854-59, pp. 289-96. Wilford Woodruff, Diary, 16 Jun e 1854, LDS Church Archives. Thirteenth Ward Indian Relief Society Minutes.

[27] Thirteenth War d Indian Relief Society Minutes, 14 Jun e 1854.

[28] Ibid., [7] and 21 Jun e 1854 and donation lists.

[29] Smith Minutes, summary following minutes for 16 Aug. 1854. Brigham Young Financial Journal, 1853-54, pp. 264-65, 267-69, 275-76, 279-80, 285-86, 296-97, 309, 311, 313-15, 318, 332, 341-42, 344, 355-56, 358, 366, 373.

[30] Ibid., p. 344.

[31] Ibid., p. 265.

[32] Brigham Young Ledgers, 1853-55, pp. 396-402, and 1854-59, pp. 289-96. Brigham Young Financial Journal, 1853-54; Isaac C. Haight and Rufus C. Allen accounts with Brig h am Young, 17 Aug.—10 Oct. 1854, Brigham Young Miscellaneous Letterbook, LDS Church Archives.

[33] On population of wards, see Bishops’ Reports for April Conference and October Conference, 1854, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[34] Brigham Young to Isaac C. Haight and Brethren and the Southern Settlements in Iron County, 18 Aug. 1854, Brigham Young Letterbook 1, p. 631 . Young to Rufus C. Allen, 13 Sept. and [9 Oct. ?] 1854, Brigham Young Letterbook 1, pp . 674-75 , 705. Brigham Young Financial Journal, 1853-54, pp. 286, 344. Indian Relief Societies received credit for $474 in Indian goods and $44 in cash after the last known shipment of goods was made to Southern Utah , 10 Oct. 1854; Brigham Young Ledger, 1854-55, pp. 396, 402 ; Brigham Young Ledger, 1854-59, pp . 289-96. Whether these later donations were also sent to Southern Utah or were used for other purposes is not known.

[35] I. C. Haight to Brigham Young, 8 Sept. 1854, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives. Young to Haight, 20 Sept. 1854, Brigham Young Letterbook 1, pp. 684-85. Young to Allen, 13 Sept. and [9 Oct. ?] 1854, Brigham Young Letterbook 1, pp. 674-75, 705.

[36] Haight to Young, 2 Oct. and 11 Oct. 1854, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives. If Haight sold clothing at less than the list price, which is likely, he distributed more than the figures would indicate at first glance.

[37] Brooks, ed., Journal of the Southern Indian Mission, p . 96.

[38] Ibid., p . 103. T. D. Brown to Young, 22 Dec . 1854, Brigham Young Papers, LD S Church Archives. Allen and Brown to Young, undated [late 1854], Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[39] Jacob Hamblin, Diary, 1854-57, entry for 21 May 1855 and notations in back of volume, LDS Church Archives. Brown to Young, 14 April 1855 and 1 April 1856, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[40] Brown to Young, 30 May 1856, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives. Juanita Brooks, “Indian Relations on the Mormon Frontier,” Utah Historical Quarterly 12 (1944): 4-15.

[41] Indian Agent George W. Armstrong to Brigham Young, 30 June 1857, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (Washington, D.C.: Gideon and Co., 1857), pp. 308—9.

[42] Brooks, “Indian Relations on the Mormon Frontier,” pp. 25-48. Floyd A. O’Neil, “The Utes, Southern Paiutes, and Gosiutes,” in Helen Z. Papanikolas, ed., The Peoples of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976), pp. 46-49. Charles S. Peterson, “Jacob Hamblin, Apostle to the Lamanites, and the Indian Mission,” Journal of Mormon History 2 (1975): 21-34.

[43] Copies of requisitions for carpeting from each of Salt Lake City’s nineteen wards, 9-10 Dec. 1854, Brigham Young Letterbook 1, pp. 779-788. This must have followed in formal notification by about a month. Patty Sessions, Diary, 2 Nov.-16 Dec. 1854.

[44] Patty Sessions, Diary, 19 Jan. 1855.

[45] In 1857 Wilford Woodruff reminded the bishops of Salt Lake Valley: “President Young had expressed a desire that in every ward there shall be a Female Relief Society established, which would be of great service to the Bishops, by relieving the poor.” Minutes of Presiding Bishop’s Meetings with Bishops, 17 Feb. 1857, LDS Church Archives. Woodruff pointed to the success of the Fourteenth Ward Relief Society, of which his wife Phoebe was president.

[46] Cedar City Relief Society Minutes, 1856-75, LDS Church Archives; Manti Ward His torical Record, 1850-59, LDS Church Archives; Spanish Fork Ward Relief Society Account Book, 1857—89, LDS Church Archives; Lucy Meserve Smith, “Historical Narrative,” in Kenneth W. Godfrey, Audrey W. Godfrey, and Jill Mulvay Derr, Women’s Voices: An Un told History of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book 1982), p. 268; Brigham City First Ward Relief Society History, 1868-1915, in Brigham City First Ward Relief Society Account Book, 1912-20, LDS Church Archives. Curiously, the Brigham City First Ward records give the best information available about the society organized in Willard. Available information about other supposed Relief Societies in the 1850s is often sketchy and contradictory, and seldom contemporary.

[47] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958), pp . 148-56.

[48] Lucy Meserve Smith, “Historical Narrative,” pp. 269-70.

[49] Wells, “History of the Relief Society,” p. 7.

[50] Cedar City Relief Society Minutes, 2 Nov. 1856. See also Linda King Newell, “A Gift Given: A Gift Taken : Washing, Anointing, and Blessing the Sick among Mormon Women, ” Sunstone 6 (Sept.-Oct. 1981): 16-25.

[51] Cedar City Relief Society Minutes, 3 Dec. 1856. Bishop Smith’s name is sometimes given as Klingonsmith.

[52] Henry W. Naisbitt, “‘Polysophical’ an d ‘Mutual,’ ” Improvement Era 2 (1899) : 741-47; Maureen Ursenbach, “Three Women and the Life of the Mind,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (1975): 28-32; John Hyde, Mormonism: Its Leaders and Designs, 2nd ed. (New York: W. P. Fetridge & Company, 1857), pp. 128-29.

[53] Minutes for 9 Jan. 1859 in Manti War d Historical Record, 1850-59, LDS Church Archives.

[54] Seventies Record, Minutes for 9 March 1845, LDS Church Archives, ss Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Salt Lake Thirteenth Ward Indian Relief Society Minutes, [7 June 1854].

[57] Arlington, From Quaker to Latter-day Saint, pp. 328, 426.

[58] Cedar City Relief Society Minutes, 12 March 1856. The speaker was Elias Morris. On the mentality antecedant to the massacre, see Juanita Brooks, The Mountain Meadows Massacre (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962), pp. 15-59.

[59] Cedar City Relief Society Minutes, 10 Sept. 1857. The speaker was Annabella Haight, wife of Cedar City Stake President Isaac C. Haight.

[60] Cedar City Relief Society Minutes, 1856-75; Brigham Young to Rhoda Snell and Adelia S. Richards, [Spanish Fork], 9 Feb. 1861; Young Letterbooks; Spanish Fork Relief Society Account Book, 1857-89; Brigham City First Ward Relief Society History, 1868-1915; Manti Ward Historical Record, 1850-59.

[61] Eliza R. Snow: An Immortal, pp. 38-49 ; [Eliza R. Snow], Brief Sketch of the Organizations conducted by the Latter-day Saint Women of Utah , Salt Lake City, 1880, holograph, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, California: microfilm, LDS Church Archives; Salt Lake City Eighteenth Ward Historical Record, 6 Sept. 1855, LDS Church Archives.

[62] Gates, “Relief Society Beginnings in Utah, ” pp. 191-92.

[63] Patty Sessions, Diary, 10 August 1854; Deseret News, 11 and 18 Jan. 1855; Samuel W. Richards, Diary, 20 Marc h 1855, LDS Church Archives. Joh n Hyde , a participant in the Polysophical Society who later left the Mormon Church, charged that Eliza Snow and a few unnamed associates exercised a sort of intellectual tyranny over Mormon women in the mid-1850s; Hyde, Mormonism, pp . 127—28. Th e apostate’s claims may have been colored by his antagonism, but apparently Sister Snow was vigorous enough to exert a formidable influence.

[64] Speaking in tongues was occasionally noted in the Cedar City Relief Society Minutes. Hannah Tapfield King received a blessing in tongues at a gathering of Salt Lake City’s Fourteenth Ward Relief Society as recorded in her journal, 3 March 1855, typescript, LDS Church Archives. Perhaps fuller documentation of other Relief Societies of the period would show a greater abundance of spiritual gifts.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue