Articles/Essays – Volume 36, No. 2

God, Man, and Satan in The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint

[1]Awell-known American novel begins with this:

NOTICE

PERSONS attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.

BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR, Per G.G., Chief of Ordnance.

(Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn)

Brady Udall has given the same sort of message to readers of his fiction. In an interview with the journal Irreantum, Udall said, “I don’t want to teach readers a lesson of any kind. I simply want them to have a hair raising, heart-thumping, mind-numbing, soul-tearing experience.”[2]

The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint is certainly not a didactic novel. How ever, like The [heart thumping] Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, it contains deeply literary and morally-informed themes and artistic material that enrich the story and raise the novel’s aesthetic power as well as its spiritual resonance.

The novel describes the suffering of a young, half-Apache boy, often in black comic style, though the events are truly horrific: he loses his par ents; he is run over by a mail truck and suffers through years of recovery; and he undergoes physical and psychological torture at a boarding school. Udall’s book is powerful, not because it captures the specifics of Edgar’s native culture, but because the author does not flinch from the suffering and evil that are endemic in life. Edgar does not dramatize his own suffering. Childlike, he takes it in stride, accepting the world for what it is. He survives simply by enduring; he just keeps moving forward. And he draws the reader irresistibly in through a vast and vulnerable human capacity for coping.

Dialogue’s reviewer complained that the book is marred by what it isn’t, an inculcation of Edgar’s distinct tribal identity. For her it sends the wrong message in the wrong voice.[3] For me, however, the book is made aesthetically and spiritually profound by what it is, a likeness of universal human experience, achieved through a combining of the engaging primary story—Edgar’s heroic journey through his youth—with the deeply Mormon cosmological world in which Udall places his hero and other characters. At the center of the action of the novel is the relationship, on the one hand, between Edgar and an old and broken alcoholic named Art and, on the other, Edgar’s ties to a one-time physician, Barry, who stalks the boy throughout the book. As the novel progresses, these relationships seem increasingly allegorical, for the relationships between man, God, and Satan in their traditional Mormon conception. Edgar is a kind of “everyman”; Art takes on the attending father role of God, and Barry mimics Satan. This spiritual, cosmological element reveals the ambition of this novel.

what is low raise and support;

That to the height of this great Argument

I may assert Eternal Providence,

And justify the ways of God to men.

—John Milton (Paradise Lost, Book I, 23-26)

I hesitate to lay out all the figurative events and circumstances in the book that I think refer to the Mormon variant of the Christian account of the relationship between man and God. For an LDS reader, one of the real pleasures of reading Udall’s novel lies in discovering these parallels. Nor will I have time in this brief note to mention all the allegorical and metaphorical material in the novel, but I will present a few key examples.

Let’s start with Barry. Many readers, professional book reviewers included, have had a hard time understanding why this alternately annoying and terrifying character keeps appearing. After Edgar, Barry is the character the reader spends the most time with. Who is Barry? At the opening of the novel, he is a young doctor, both driven and caring, who saves Edgar’s life after his horrific accident with the mail truck. But when Barry does not get the credit he thinks he deserves for saving Edgar, his sense of injured merit and thwarted ambition quickly destroys his career as a doctor. He is forced to leave the hospital—significantly named St. Divine’s—that is, he ceases to be a chosen angel. “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!” (Isaiah 14:12) He soon becomes a drug-dealing devil, ever at Edgar’s heels, trying to bring him into his orbit of influence. As Satan had his own plan for mankind’s salvation, so does Barry for Edgar.

Let me mention a couple other points about Barry’s allegorical identity. In the Utah sequence, when Edgar is in the Indian Placement Program, Barry seeks to get close to the boy through flattering and tempting Edgar’s foster mother, Lana. What goes on between Edgar’s foster par ents and Barry clearly parallels events in the Garden of Eden. Lana, married to Clay (like Adam, “of the earth”), is the more educated and inquisitive of the two. Just how successful Barry is with his seduction of Lana is unclear, but there is no doubt about what is going on: Lana and Clay, Edgar’s adoptive parents, are in a struggle with Barry over the boy’s future, just as Satan entered the Garden and contended with our first par ents over the future of humankind.

Why does Udall devote so many pages to Barry? Udall’s first book, the collection of stories entitled Letting Loose the Hounds (Norton, 1997), conveys a rather dark view of the world. His characters have to contend with Barrys much more than they get to spend time with people like Art.

From the diabolical to the divine: The very choice of Art’s name suggests creation. Moreover, Art in his own way is certainly a shepherd for Edgar, a role to which his surname—Crozier—points. (A “crosier” is the shepherd’s hook used by high-level officials in several Christian churches.) Art and Edgar meet in St. Divine’s hospital, and as Edgar be gins to recover from his accident, Art watches out for him. In this passage, Art assists Edgar in getting loose from the restraints of his hospital bed while at the same time he helps Edgar move from his bed to solid ground:

[Art] unbuckled the restraints—it took him awhile to figure them out with only one good hand—then stole every pillow and blanket he could find in the room and placed them around my bed, creating a landing pad. That night I threw myself off the bed twice, and both times Art was there to help me back up, make sure I didn’t have any lasting injuries, and to argue with the nurses when they came in wanting to know why the restraints had been taken off.[4]

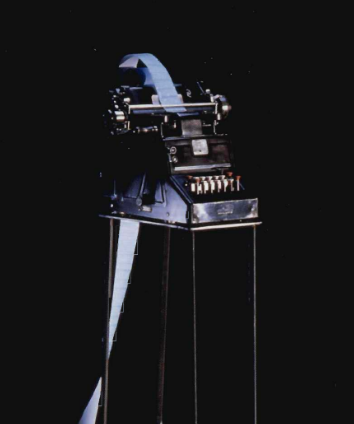

Before Edgar leaves the hospital, Art gives him an old manual type writer, a “Hermes Jubilee” model (Hermes is a messenger of the gods in Greek mythology). Throughout the book, Edgar types out his thoughts, his fears, and occasionally, letters to Art, which like prayers or petitions to God go unanswered in any literal way.

I find Art to be moving especially as he is not depicted as omnipotent or all-knowing or even as particularly virtuous. He is flawed, an-all-too human Father on Earth, and like Edgar, he too suffers. Art, desolate and lonely, “has descended below all things.”[5] That is how and why he understands Edgar. The anthropomorphic view of God is, I think, the most Mormon aspect of the underlying theology of the book. It is extreme, probably heretical, but like the Cowboy Jesus in Levi Peterson’s The Backslider, I find it deeply moving. Art cannot save Edgar from suffering and pain; he is limited by the universe they both live in. What he can do is be there when needed to show that he understands and that he cares.

I treasure this traditional Mormon anthropomorphic view of God. I don’t mind at all that God might be finite, subject to the constraints inherent in the physical universe. I feel more comfortable with a contingent than with an absolute deity, one who is more like than unlike me in nature.

Towards the end of the novel, Art and Edgar meet again. (For me the scene has clear parallels with LDS temple worship.) We find that Art treasures the contact he has with Edgar: he needs it to get himself through his own suffering. In Udall’s vision, both acolyte and master are co-sufferers. I find the notion that Edgar and Art need each other to help give meaning and substance to their lives profoundly theological. I think this is one of the most forthright books I have ever read about how happiness and divinity, suffering and evil, really do work in our lives. In a recent interview Udall said:

[T]hough I’m not the most spiritual or religious guy in the world, I know that God plays a central role in the lives of people everywhere. It’s hard for me to understand why so many contemporary writers seem to be reluctant or downright afraid to confront God in their work. I guess I write about God because God is in our lives, whether we want Him there or not.”[6]

One of the amazing aspects of this book is that one can read and enjoy it merely for its rousing, touching, and often very funny story, while remaining unaware of the theological elements I have discussed here. You do not need to see the theology to enjoy the book though in my case it certainly gives the book even greater aesthetic and spiritual power. At times in the novel Edgar’s mundane world and the deeper theological world in which Udall has placed him come together and merge. God chooses Edgar; then Edgar chooses God:

The Elders taught me all they could and I tried my best to get it all sorted out. I learned that my mother and I could be reunited and live on together into eternity where nobody got old or sick or—Elder Spafford promised me—bored. I learned that Jesus, God’s only son, had suffered for every one of my sins, for all the guilt and sorrow they caused. This did not seem very fair to me, but I kept my mouth shut. I learned that cigarettes, beer and coffee were all no-nos, and that chastity, which I understood to mean keeping away from females entirely, was a must. And most importantly, I learned about this God who presided over this place called heaven where my mother was, who had a plan for me, who loved me without qualification, who watched over me. God, I learned, would never die, would never disappear without notice, would never beat anybody up, would never grow sick or old or tired of living. He might become angry or disappointed, yes, but He would never abandon you.

Okay, I would accept Him, I decided. I’d have to be an idiot not to.

So, I typed Him a little prayer that said: God. This is Edgar. I will take it.[7]

[1] Prepared for the Association of Mormon Letters conference, February 2003.

[2] “Interview: Brady Udall,” Irreantum 3, no. 4 (Winter 2001-2002): 15.

[3] P. Jane Hafen, “Speaking for Edgar Mint,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 179-181.

[4] Brady Udall, The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint (New York: W. W. Norton, 2001), 34.

[5] See D&C 88:6, 122:1-9, esp. 8.

[6] Brady Udall, “Interview,” available at http://www.bookbrowse.com.

[7] Udall, Edgar Mint, 226-27.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue