Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

Guest Editor’s Introduction

Who would have dared to predict in 1830 that a tiny, radical circle of religious seekers around the Joseph and Lucy Smith family would be a church of 10 million only a few generations later at the dawn of the twenty-first century? The answer: Maybe the irrepressible and visionary prophet Joseph Smith, Jr., but scarcely anyone else. For that matter, who would dare to predict now that by the middle of the twenty-first century this same church could increase at least ten-fold to 100 million or more? The answer: More than one expert! The most engaging of these is non-Mormon sociologist Rodney Stark, whose predictions about Mormon growth were first published in 1984 and have since been updated.[1] His optimistic projections have so warmed the hearts of the faithful that they are often quoted over the pulpit, even in general conference now and then.

Church growth during the past decade, at least, has matched or exceeded Stark’s projections, thereby lending credence to his longer-term expectations. Yet Stark was not the first to track Mormon growth trends into the future. As early as 1969 Mormon economist Jack W. Carlson published in Dialogue his projections to the turn of the century, covering not only church membership but also average household income of Mormon families![2] A generation later these ambitious projections seem surprisingly accurate, though slightly short of the actualities. Carlson has American church membership reaching 6 million by the year 2000 (it is already at 5 million), most of it in suburban residential areas, and an additional 2.5 million outside North America (already more than 4 million), for a total of 8.5 million out of a world population of 5 billion. These figures can now be seen as underestimates, but not by very much.[3] Up to the year 2000, at least, Carlson’s estimates converge reasonably well with Stark’s to that same point, though made from a greater temporal distance.

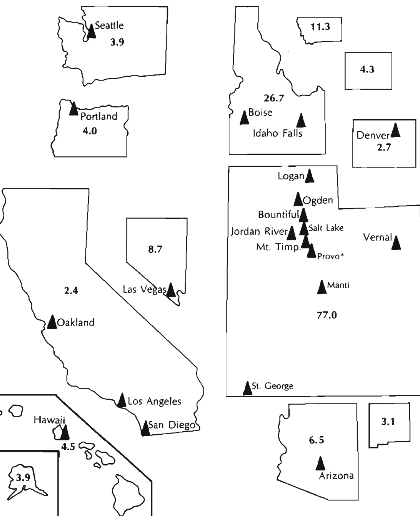

The projections of Ben Bennion and Larry Young, in the first article presented here, go only as far as 2020, when they estimate a worldwide church membership of about 35 million, more than triple the current figure. Since membership has tripled during the past twenty-five years, it is not extravagant to estimate that it will triple again in the next twenty-five, though Bennion and Young are too cautious to take their projections farther into the next century, as Stark has done. Yet another tripling in the twenty-five years beyond 2020 would take us to the 100 million or so that Stark has envisioned by the middle of the next century. Of course, demo graphic projections get more tricky with temporal distance; and in the case of a new religion (which is what Mormonism is everywhere but in the U.S.), they are especially contingent on variables that are almost im possible to estimate with any precision. That is why, as Bennion and Young show, the regional projections embody greater fluctuation and, when combined, yield a somewhat higher total than we get by making more composite projections for the world as a whole. It seems, in other words, that the whole is smaller than the sum of its parts in this case.

The fluctuating variables in question include differential rates around the world not only of conversion but of marriages, births, deaths, and (perhaps most of all) retention. It is obviously not enough to reap only where the “field is white and ready to harvest.” If the field is small to begin with, or if some of the seed does not germinate, or if some of the ripe grain is lost to disease or weather, the harvest will not be large in that particular field. Similarly, even with a good initial harvest, large quantities of grain can be lost in storage if great care is not taken to guard against rot and rodents. Then, of course, there are those fields that never seem to “ripen” for the harvester’s sickle. Thus, one wonders, how much of the Latin American success story for Mormons (and, indeed, for Jehovah’s Witnesses and Assemblies of God) can be attributed to the sheer sizes of the birth rates in most of those countries, which insure a steady supply of young people and young families, the “ripest” of all potential converts. Conversely, how much of the seeming “stagnation” in Mormon growth in Japan or in northwestern Europe can be attributed to the relatively small birth rates in those countries? Or is it that most of the “grain” in those highly secularized societies never seems to “ripen,” given the unfavorable “spiritual climates” there, as some of our later essays seem to suggest? In short, how important, respectively and relatively, are demographic factors versus socio-cultural factors in the conversion and retention of LDS members?

Let us be clear at the outset that we cannot adequately explain the growth or success of the church anywhere in the world on the basis of social science knowledge alone, whether we are talking about demo graphic, political, social, or cultural factors. Surely much of the explanation will always lie with other influences (including the spiritual) that are scarcely understood by social scientists. Although much of the readiness or susceptibility of a given people for the gospel message can be understood in human or social terms, how do we account for the fact that similar social conditions yield very different rates of conversion from one country to another, or even within the same country? The “ripening” of a people for a missionary harvest has much to do with how they respond to their social conditions (whatever these are); and that seems to be a spiritual matter less amenable to social science prediction or explanation. In dividual missionaries in the right place at the right time, whether through divine intervention or not, can also have a powerful spiritual im pact on the conversion process. One thinks, for example, of the special power of Paul’s preaching in New Testament times or of Wilford Woodruff’s in England during the 1830s and 1840s.

Yet, even with a spiritual interpretation, one can easily understand that the divine hand might well use social and political conditions to prepare a people for the missionaries. Other human factors also reveal themselves in the differential skills (and results) that we see throughout the church in the strategies and tactics of missionaries and of local leaders as they strive, no matter how prayerfully, to do the work to which they have been called; for, obviously, equally spiritual and conscientious servants of the Lord do not produce equal results. Clearly, therefore, the spiritual and the social science explanations for missionary success are more complementary than contradictory. The essays in this special issue have thus been prepared on the assumption that social science explanations can contribute to our understanding of church growth and success, present and future, without excluding spiritual explanations but adding to them.

When Dialogue editors Martha Bradley and Allen Roberts encouraged me, some two years ago, to put together this issue, I was very ap prehensive about the eventual outcome. I had sworn years ago that I would never again put myself in a position of trying to enforce deadlines on other authors. As things turned out, however, the process went more smoothly than I had expected. We began by casting as wide a net as possible in an effort to recruit knowledgeable authors. In addition to calls for papers that appeared both in Dialogue and in the Newsletter of the Mormon History Association, we sent personal letters of invitation to some 80 scholars. Eventually a dozen or so responded with commitments to contribute papers. Nearly all of those came through with the contributions that you see in this collection. We hope you will be pleased with the work that all of us have done.

Without the gift of prophecy, which none of us would claim, how does one make credible prognostications about the future, even a future as close as the twenty-first century? The best we can do in most cases is to study the present and the immediate past in order to tease out trends likely to persist into the future. As a matter of editorial policy in this is sue, we have deliberately slighted history, especially the more distant past, in order to give the collection a future-looking orientation. In some cases, the trends have seemed fairly clear; in others, considerable imagination has been required to estimate the future. In all cases, the authors have tried to be appropriately humble and cautious about their predictions. We have thus been more willing to identify likely future issues and problems than to propose solutions or to predict outcomes. Some of the papers point to options or possibilities that might be helpful in resolving certain problems, but it is not the scholar’s role to instruct church leaders in solutions. Yet we hope that some of what we have to say will prove useful to anyone interested in the future.

We have tried to employ a perspective that is serious and realistic without being somber or negative. All of the contributors are members of the LDS church, many actively involved. All of us wish the church well, not only in the twenty-first century but all the way to the Millennium! Speaking at least for myself, and I believe for the rest of the contributors as well, we gladly associate ourselves with the remarks made by President Gordon B. Hinckley at the concluding session of the October 1995 general conference. He deplored the tendency for some observers to cry doom and gloom about the future of the church and called on all of us to go forward with optimism and enthusiasm in church service. We presume, however, that no one would have us advocate a naive triumphal ism in considering the future prospects of the church; neither the Lord, the church, nor its members are well served by such head-in-the-sand assessments.

For the fact is that the church will have to deal with many serious problems, present and future, if it is to continue to enjoy its recent rates of growth in the world, and particularly if it is to retain the active commitment of its members and their children. We have little doubt that most of these problems are well known to church leaders, general and local, so what we are offering here are perspectives, and perhaps a few suggestions, rather than new “revelations.” No matter how knowledgeable church leaders themselves might be about the matters to be discussed in these pages, most members of the church are not so knowledgeable. Thus we hope that our readers will benefit from our efforts here, perhaps gaining insights that will help them as partners in building the Kingdom.

Some of the essays in this issue would have benefitted by access to data gathered and maintained under official church auspices. Several of the authors, indeed, explicitly sought access to such information but could not obtain it, given the strict proprietary controls imposed on most church-generated data. Fortunately, however, much valuable information was still available from more public sources. In a few cases, furthermore, local church leaders were willing to share what they knew (if only anonymously) out of personal trust in an author’s judgment, balance, and fair ness. We have tried to vindicate that trust. Furthermore, many of the papers rely as much on personal experience for their “data” as on external or archival sources. This is particularly true of those authors with experience from outside North America. While personal experience is not systematic, and therefore cannot be easily generalized, it nevertheless is still empirical, for it represents the observations of “expert witnesses” and “native key informants,” as they might be called in anthropological field work. Our key informants in this case, furthermore, have been immersed in Mormonism for decades as active members and leaders. Their passionate and sincere concern for the future of the church sometimes breaks through in their writing, but their observations can hardly be dis missed as merely emotional or impressionistic, given the depth and breadth of their LDS backgrounds and church experience.

This unique collection of papers reflects implicitly the assumption that the future of Mormonism in the next century depends largely on what happens outside North America. Accordingly, while a few of the es says deal with general topics like scriptural interpretation or science, most focus on countries or regions outside the U.S.: Latin America, Eu rope (north and south), Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. We would like to have included a paper on England or the British Isles, where half of all Mormons in Europe reside. However, no such paper was offered, despite some solicitations.[4] Perhaps some inferences can be cautiously generalized to the British scene from what we learn in observations about Australia and continental Europe.

The issue begins with the Bennion-Young geographic and demo graphic overview of Mormon growth in the world, followed by the Shep herds’ study of missionary activity as the engine of that growth. Together these papers provide a strong empirical context for understanding much of what follows. One thing clear from these two essays is the strong circular or reciprocal relationship between member retention and missionary mobilization; as either one of these drops off, so does the other, and each serves to intensify the impact of the other on future church growth. The next two papers deal with issues that will be relevant anywhere in the world in which the church achieves or maintains a significant future presence. Karl Sandberg examines contrasting perspectives that have developed among Mormons on how best to understand and interpret scripture, doctrine, and the teachings of modern prophets, and he wonders which will be the dominant hermeneutical mode of the future. David Bailey reviews the related issue of how doctrine is to be articulated and reconciled with the rapidly emerging discoveries and understandings in the sciences.

The remaining papers all deal with settings outside North America, and despite the obvious cultural differences among these settings, these essays all illustrate certain common problems faced by Saints striving to make an essentially American religion work in other places. The first two of these, Walter van Beek’s from Holland and Wilfried Decoo’s from Belgium, make clear (among other things) that the American connection no longer contributes either to conversion or to retention in those countries; in some ways, indeed, it is an obstacle. One suspects that the same is true in most of western Europe. The commitment and endurance of the Saints who remain faithful in those small and slow-growing LDS congregations should evoke the admiration of those who live in the thriving but complacent wards of western America. In southern Europe, to judge by Michael Homer’s example of Italy, the recent end to the Roman Catholic legal monopoly was followed by an initial spurt of LDS growth, which is now proving difficult to sustain in that part of Europe. Interestingly (and perhaps ironically), a perceived similarity between LDS and Catholic values and authority structures contributes somewhat to LDS conversions there, although the church still has a long way to go in overcoming its image as a weird American cult.

Difficult as LDS proselyting might be in Europe, it has been enormously successful in Latin America, though probably not as successful as that of Protestant pentecostals and other groups. Yet, as David Knowlton points out, it is hazardous to generalize about Latin America, which, after all, comprises many different countries. There is, in fact, a great deal of variation in LDS success among the various Latin American societies for reasons that are not all obvious; and again the U.S. connection is a serious drawback in certain ways. One fascinating attempt in Latin America to deal with the Anglo-American bias found in traditional Mormonism can be seen in Thomas Murphy’s account of local efforts in Guatemala to “re-invent” or adapt the message from up north in ways that will enhance local pride in their own ethnic heritage. One wonders if there is enough flexibility in Mormonism to permit such local adaptations outside the core of basic doctrine; if so, we can look forward to a variety of Mormon isms by the end of the next century.

The remaining papers take us to the Pacific island nations of Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, each of which presents its own cultural complications to the LDS enterprise. At the same time all are “First World” countries (like western Europe) dominated by secular climates in which traditional religions retain only limited popular appeal. According to some contemporary theories, such a setting is fertile ground for the rise and spread of new religions. However, opportunities for the LDS church to expand there are constrained by various historical encumbrances. In Australia, as Marjorie Newton explains, the church is still struggling with the consequences of “hard-sell” missionary tactics tried a generation ago, which (as in England’s era of “baseball baptisms”) severely damaged the LDS public image and left the church with a large proportion of only nominal—or even hostile—members. A similar development has occurred in Japan, and church growth there is further con strained by a powerful, assimilative culture which has never allowed much room for any form of Christianity, and which is now as much permeated with secular, agnostic, and material values as any Western nation. In New Zealand, where the church has historically enjoyed great success among aboriginal Maori people, it has in recent years found itself drawn into the national political struggle for Maori cultural preservation and autonomy. While the New Zealand situation is unique in some ways, it also provides an example of the kind of quandary that the church can expect increasingly to face in multi-ethnic nations, not only elsewhere in Polynesia, where the LDS presence is already strong, but in other emerging nations.

In the final essay I have tried to highlight certain present and future issues affecting church prospects in the world and to provide a general theoretical perspective that views those issues in the framework of “religious economies” or “religious markets.” This perspective has become the dominant “paradigm” in the sociology of religion during the past de cade or so, and it offers a new and challenging way of assessing prospects for Mormonism around the world during the coming century.

Enjoy your reading!

[1] Rodney Stark, “The Rise of a New World Faith,” Review of Religious Research 26 (Sept. 1984): 18-27. Stark’s updates, publicly reported in recent oral presentations but not yet published, indicate that his 1984 projections might have been somewhat conservative. Stark has also studied demographic, economic, and cultural correlates of Mormon growth in various lo cations. See his “Modernization, Secularization, and Mormon Success,” in Thomas Robbins and Dick Anthony, eds., In Gods We Trust: New Patterns of Religious Pluralism in America, 2d (Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1990), 201-18; and “Modernization and Mormon Growth: The Secularization Thesis Revisited,” in Marie Cornwall, Tim B. Heaton, and Lawrence A. Young, eds., Contemporary Mormonism: Social Science Perspectives (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 13-23.

[2] Jack W. Carlson, “Income and Membership Projections for the Church through the Year 2000,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 4 (Spring 1969): 131-36.

[3] Carlson also estimated median family income for the year 2000 among U.S. Mormons (surely a more difficult task!) at $23,000 in 1968 dollars, which might be an overestimate if we triple that figure to reflect 1995 dollars, but again not enormously off base.

[4] Actually, a few knowledgeable potential authors, especially some who are BYU-connected, declined to participate for reasons that were not always clear.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue