Articles/Essays – Volume 36, No. 2

Havesu

He watches Elain’s buttocks, the tan shorts browned at the seat, as she walks briskly ahead of him on the narrow trail. Her dirty orange day pack bounces on her back, the leaky canteen a long wet lump on the right, the camera a squarish bulge on the left, separated by the other things she’s stuffed in—toilet paper, hand lotion, capless ballpoint pens, little sticky rectangles of sugarless gum, and a ragged paperback, so she’ll never have to waste time. In honor of nature on this trip, she’s left behind Isaac Bashevis Singer and has limited herself to guidebooks on plant and animal life in the Grand Canyon.

When Rob first met her, six years ago now, at Jody’s flat, she was smudged and sweaty after a twenty-hour charter flight from Tel Aviv, two jolting bus rides from Kennedy, and a four-story climb from 93rd Street proper. She dumped that same dirty orange pack upside down on Jody’s mohair rug. “I’ve simplified my life,” she said. “These are all my possessions.” There were, he remembered, some travelers’ checks, her passport, a Swiss army knife, some cotton underwear and t-shirts, all stamped with the Hebrew letter aleph by a kibbutz laundry, a camera with sand gritting somewhere in its innards, a poetry anthology dating from her undergraduate years at the University of Nevada, and a blue paperback copy of the Book of Mormon that she said she’d stopped read ing but was holding onto for sentimental reasons. She’d given away a cheap guitar and the rest of her clothes. Finally, however, she admitted to owning boxes of books and a carton of aunt-embroidered dish towels and box-top-bought stainless steel spoons and forks—no knives—all of which arrived just before they were married.

The orange pack suddenly looms larger. He slows his step, so he won’t run into her; she hikes unevenly, racing for fifteen minutes, then dawdling for twenty. She holds a pronged ocotillo branch aside for him now. “Careful. I’m too poky for you.”

“Poky.” He pokes at her ribs and she sucks in her stomach. “Funny word, poky. Poke. I wonder what it means in cowpoke.”

She shrugs. “You could still run on ahead, you know. You could probably catch the boatmen if you went now.”

“I’ll stick with you. Even if I won’t get a Technicolor, wide-screen ac count of Terrill sleeping with the queen of Siam.”

“He didn’t sleep with the queen of Siam,” she says. “Did he?”

“Elaine,” he says. “Keep walking.”

She speeds up both her step and her speech. “Look,” she says, “you’ll wish you’d gone when they get back and start talking about it. You’d get to see Moony Falls and maybe the reservation. You could take the camera. Get some pictures of the stone gods the Indians used to scare their children.”

“The stones aren’t the gods. The stones are the children. Bad children got turned into stone.” With one hand he slaps at a bug trying to burrow through the stubble on his face; with the other he searches his pockets for the Cutter’s. “I can carry the camera though.”

“No. I want to carry it.” She feels around her back with her left hand, pats the bump. She is talking over her right shoulder. “You’ll have to work up gradually again to your daily ten miles. Hanging onto a raft and hiking a little won’t do it. Especially eating like porkers. Maybe if you rowed. How many miles would you have to row to equal running ten?”

“I don’t know.” He spreads insect repellent on his hair for good measure, then shifts his attention to the creek. A river really, it spreads out, rolls over a flat layer of rocks, drops half a foot. They’ve come about a mile from where it laps into the Colorado, from where they left the rafts tied up, one to another in the surprise inlet in the sheer limestone walls. “Why don’t you get a picture?” he says.

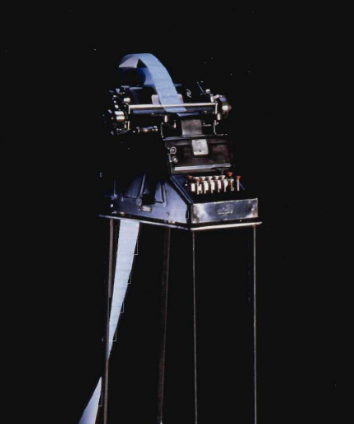

She squirms out of the backpack, reaches in. Fiddling perfunctorily with the adjustments, she aims at the foam and snaps. She drops the camera again into the pack. She lost the lens cover a week after he’d given it to her, a Christmas present to replace the series of sandy instamatics.

The canyon is green. Like spring in the canyons back home. Old home, that is, the Wasatch Range, the Uintas, where he used to go off by himself summer days—biking the old three-speed up two-lane highways with camp stove and sleeping bag weighing down the rear tire, or packing in with Eddie, who always got nosebleeds at high altitudes. One time they were flushed out of a canyon with their homemade kayak. They wrecked on the rocks and crawled up the bank just in time. Borrowed truck bed empty, they drove, squeaking with mud and sobered with fear, back down to the valley. They didn’t bang the back screen, but Mom wailed, “Don’t sit on anything, don’t even stand there, get straight under the shower,” while LaNell and Lou Anne, big sisters, always virtuous and clean, squealed their disgust. Mom and Dad and Eddie the Unmarried still hold down the purple brick house with the bent tree in front. LaNell and LouAnne long ago moved to their own brick houses. Only LaNell is dead now, proving God knows what. If God knows. If God.

“Are you thinking about your long-lost youth?” Elaine shakes her hands as she walks. Her fingers swell, are constricted by her rings.

“Actually, I was thinking about certain economic indicators for the international plastic market.”

“You were thinking about your past. What were you thinking about it?”

He shrugs even though she can’t see him. “It’s long lost.” He side steps something whipping across the trail into the brush. Something reptilian probably. “I was thinking,” he says, naming something safe, “of snipes.”

“Oh,” she says. “Snipes. We went on a snipe hunt once.” She talks to the left side, so he can see part of her cheek. “At Lake Mead. The bigger kids gave us paper bags and parked us there, told us to wait for these great big birds.” She shapes one with her arms. “We waited for hours before someone came and told us we were wasting our time.”

“Hours?”

“Well,” she concedes. “Maybe forty-five minutes.”

“Snipes don’t even live in Nevada,” he says. “That’s why you were wasting your time. Snipes live in Utah. And you could never catch one in a paper bag. We once gave a pack of Cub Scouts some gunny sacks, told them to wait on the hillside. We gave them a nicely detailed description of a snipe. Scales. Big nose. Stringy neck. Gold-plated molars. Everything we could think of. We told the kids to crouch down on a rock with the gunny sacks open and to whistle as high as they could. Snipes have very acute hearing, you know. If you whistle just the right notes, the snipes will run into the gunny sacks. Know what one of the kids said?”

“What?”

“‘What’s a gunny?'”

Elaine laughs. “Gunnies are even bigger than snipes, you should have told them. They eat goats.”

“After which they burp and belch and suck blood,” says Rob.

They are moving along the trail fairly fast now. Most of the group is behind, but there are several fresh tread prints when the trail is dirt, not rock. The thin-ridge soles are Terrill’s. He and Andy spurted off as soon as they’d tied up their boats. The Sacramento soil engineer, Jerry P., had galloped after. Rob wanted to, Elaine is right, but Terrill—born-again blowhard, instinct epitomized—it’s bad enough to watch him perform in public. Rob didn’t think he could handle a private showing. Besides, Elaine keeps going distant on him. He wants to stick around. “Hmm,” he says to her back, “what was easier to believe in—Joseph Smith and visiting angels or snipes and gunnies?”

A knee-high boulder blocks the trail. She sits on it, swings her legs over. “Not a fair choice,” she says. “We didn’t grow up singing songs about snipes every Sunday.” She brushes off the back of her shorts, but since her hands are dirty, she makes the smudge worse. “Hey,” she turns back after a few steps, “I still believe in gunnies.”

This is a comfortable little canyon, he thinks. The main gorge isn’t intimate and overgrown like this. It’s vast, indifferent in its millions of years, the perfect antidote to human pride. Yet somehow the natives believed they mattered, mattered enough for gods to seek out and punish them. On the canyon walls, the Havusupai stone babies; in the depths of the gorge, the remains of a retributive, earth-swallowing flood. Some tribes, he has read, have thought the Colorado their own road to hell. Some have believed in a god who inundated the road to Paradise—so human beings wouldn’t try to sneak over the boundary.

According to the boatmen, most obstreperously Terrill, the whole Grand Canyon is Paradise, not the way to or the way from. Paradise. It sounds like the name of an Atlantic City amusement park. Mormons believe Paradise is a kind of check point in an endless cross-country race. He tries to remember the party line. Christ preaches there to the dead. Folks already prepared and repentant jog on towards a heaven which is itself a par-course to another trail to. . .Rob ducks under an ocotillo branch that Elaine has cleared with an inch to spare. Mormon Paradise isn’t like Jewish Paradise, at least according to the Singer stories Elaine likes to read aloud. Nor like those other pastoral places, banana pudding in the sky and all.

He kicks at one of Terrill’s thin-ridge sole prints. Earth of course is an exhausting place too, even for ex-Mormons, if there really is such a thing. Rob has suspected for some years now that there isn’t. Alienated, repudiated, even excommunicated—which he isn’t and doesn’t want to be— Mom would suffer too much, maybe even he would suffer—there never is a final break. B.R. doles out cocaine and Rob not only shakes his head, the small white cups make him think of the sacrament and he shudders inside. He doesn’t contribute to, can’t even laugh at, the luncheon discussions of the Hindu sex positions. And before he’d met Elaine, he had a very nice, very bright, very pagan girlfriend whom he saw only once after that first night at Jody’s and that once to tell her goodbye. Elaine had a chance of understanding, he figured, about the faith that no longer securely folded him.

He bumps into her now, not noticing until the back of her head hits his chest that she has stopped. She takes a quick step forward and points at the cliff ahead. “Where’d the trail go?”

He looks around. “Over there. They said we’d be fording the creek. This must be the place.” He repeats that with a gravelly voice. “This is the place.” Elaine is unamused. Grimacing, he plunges into the water. It reaches his waist.

“It’s deep,” she says.

“Come on. You’re the swimmer. Anyway I’m waiting for you.”

She takes a few steps in, is up to her chest. “It’s cold!” A few more steps and he grabs her outstretched arm. The rocks feel slick and spherical; they teeter on them as they push against the water and across the current. He boosts her up to the opposite bank to the trail. The wet shorts wrinkle around her bottom. The lower half of the daypack is wet. And probably the camera. He sighs. Oblivious, she trots on ahead, squeaking water out of her running shoes.

She bought those shoes three or four years ago, has used them for everything but running. The plan was to try a mile or two in the mornings with him. She never really got into it. “It’s not any fun,” she’d say. “I’d rather ride the rec club exercycle. At least I can read while I’m pedaling.” She took up racquetball for a while, with Jody, but that didn’t work out either. She finally settled on swimming—the one sport he dreads—maybe since the kayak splintered in Logan Canyon. She’s good at it, too, likes the feel of the water on her body, she says, likes the stretch. She comes home late from work three days a week, hair wet and dark, slicked back behind her ears or tied in two stubby bunches at the sides of her face. “Two kilometers,” she says,” or “Can do the butterfly ten minutes straight now.” When she’s pregnant, she tells him—they’re talking about it, maybe next year—she’ll be able to swim up until the last moment.

Before them a sneeze punctuates the silence—Andy grinning and wiping his nose on his bare, brown arm. “Allergies,” he sniffs, “to spring things. Flowers. Pollens.” He blows his nose into a blue bandanna he pulls out of a tight pocket in his cutoffs.

“You already been up to Moony Falls?” Elaine asks.

“Just patrolling the trail. You found where to cross, I guess.” He grins again, wide and toothy. He has a deep scar next to his right eye, and it crosses with wrinkles when he smiles. “I’d better get back to the ford,” he says. “Didn’t mean to let you cross on your own.” He sidles past.

“I like Andy,” Elaine says when she judges he is out of earshot.

“You like everyone.”

“No I don’t. I don’t like Lona much.”

“Why not?” He doesn’t like Lona because she’s so severe, frenetic, so narrow-hipped, tight-lipped, but Elaine often talks to her at dinner. He thought of them as friends.

Elaine bends down and peers at a big-petalled orange mallow. “Maybe,” she says finally, “because I’m something like her. That’s a pretty common reason for disliking people. We dislike people we can compare ourselves with. Isn’t that why you dislike,” she pauses shrewdly, “certain people?” When he is silent, she straightens up, looks at him, trots on.

To himself he thinks, me, comparing myself with that big-mouthed boatman? Terrill. What do we have in common? Even his name sounds manufactured, Hollywoodish, like the names of the women he is always, according to him anyway, humping—Tiffanies and Sheilas and Jessicas and Kims. But he is good with the oars. Rob can tell by the way the other boatmen act. And he’s got the women hypnotized. Even Elaine, who’s usually distrustful of muscle men and Jesus freaks.

A Jesus freak. That at least is original, Rob thinks. It is so original that Terrill couldn’t have made it up. It doesn’t compliment the Hemingway he-man crap. He must really believe it. Well. He slaps at another insect. Most of us did. Once.

There are shrill shouts on the trail ahead. Elaine turns around, looks at him. “What’s that?” she asks.

“Snipes,” he says.

The whoops take on bodies, a clump of khaki-clad kids with wet, rolled-down socks. “Hey mister,” says the first one, a blond boy of about twelve whose shirt, still buttoned at the waist, hangs down about his shorts. “How far to the river?”

“Two miles,” Rob says, “maybe three. Where’d you come from?”

Information acquired, the kid isn’t interested in chitchat. He whistles at the Scouts bunching up behind him. “Two more miles, guys!” He shoots past. The others bump along after.

Twenty years ago, Rob thinks, Mom would iron his army drab uniform and mustard scarf, so he could march like a little Nazi in a down town parade or pant, too warm, on a mountain hike or scrabble with similarly suited little fellows in the church parking lot. On the trail ahead a sweating man in a large uniform leans against a big rock. His hair is stuck to his forehead. He seems to be breathing too hard to talk. He raises his eyebrows in a question and motions with his head the direction of the boys. Rob and Elaine nod, respecting his silence. He sighs and raises a foot, clumps heavily down the trail.

“If he’s in such bad shape going downhill,” Rob steps around a hedgehog cactus, “he’ll probably have a coronary on the way back up.”

“You could be a scout leader,” she says.

“Huh?”

“I mean if we ever became Mormons again. I don’t think scout leaders have to believe anything so long as they can tie knots.”

Rob stops, stunned. “What are you talking about?’ he starts to say, but distracted by a redbud tree, she is fishing the camera out of the day pack.

Her forehead creases, the foretelling of tears. “It’s wet.” She hands the camera to him.

“I should have carried it,” he says as gently as he knows how but not gently enough.

She sucks in both lips. “Don’t you take the blame. You’ll just resent it when you start thinking about it. It’s my fault.” She sounds almost proud. “I’m sorry.” She doesn’t sound sorry. “I was careless.” She pronounces “careless” as if it were two words.

“You weren’t careless,” he says. “You were just short.” He pushes the camera back into her pack, brushes her hair aside and touches her neck. “Come on. Someone’ll catch up.”

“So what?” Her voice is strained.

“It’s nice to have a few hours alone. You handle communal living better than I do. You had that kibbutz experience.”

“Anyone who can live wedged in among ten million people for nine years ought to be able to handle twenty for two weeks.” She takes long steps away from him. “Listen,” she says. “Must be Beaver Falls.”

The trail forks, the lower path ending at the base of a dozen short flat cascades terracing the widened river. The less traveled path climbs the cliff, where shirtless, sunning like a large lizard, Terrill perches on a rock. “Hey,” he sits up on his haunches, “wanta swim up to the second floor?”

“I thought you were hiking to Moony,” Rob says.

Terrill closes his eyes and smiles. “Hiked up a few miles,” he says, “to show Big Jerry the way. Thought I’d come back and show you the intermediate sights.”

Elaine’s eyes are bright. “What’s behind the falls?”

“More falls,” Terrill says. “Prettier ones. Come on. I’ll show you.”

Elaine dumps the backpack with the ruined camera on a rock, peels off her already wet shorts and shoes, and wades into the same river she had nervously crossed below.

“Isn’t it still cold?” Rob says.

“No. More sun here.” She is suddenly gone, having apparently stepped off an underwater ledge. She reappears, sputtering, giggling, her hair molded to her head. “Don’t you want to come?”

He doesn’t, but Terrill is standing, overlooking the whole scene, so he shucks shoes and shirt and steps into the water. Elaine splashes over the rock rim that forms the low falls, her t-shirt sticking to her back. Now she is breast-stroking easily in the pool beyond.

As soon as the ground drops away, he panics. The banks are close, he tells himself, he can always swim that far, but the water is so cold he can’t breathe right when he tries the crawl. Elaine is in the middle of the pool now, paddling and shouting up at Terrill. “Now what?”

“You okay, Rob?” Terrill asks. He peers down from his cliff.

With wild strokes, Rob pulls himself over the bank and climbs up. “Too cold for me,” he shivers. “I’ll wait here.”

Terrill nods. Then he plummets into the water, sneakers first. He bobs up next to Elaine. “Come on!” he says and swims off against the narrow rush of water. She follows. They are out of sight in a second. The churning water drowns out all sounds beyond. There goes my wife, Rob thinks, in her underpants, with a boatman. He settles on a rock and lets his feet sink into the mud. Briefly fascinated and repelled, he analyzes his own fear, envy, shame, disgust, relief. Then he thinks about practical things. He might as well try to get back to the trail end before anyone else arrives to see him stranded, abandoned.

If he sticks to the edge of the pond, hangs onto the sides, he can prob ably avoid the drop-off. The ragged rocks jab at his feet and pimple his hands, but he makes it to the base of the falls without getting his head wet. Sitting on a rock next to Elaine’s shorts, he extracts the camera from her daypack and examines it. It doesn’t rattle. Maybe a good shop can do something. Some things can be repaired. He pulls on a sock. There is a trickle of blood along the side of his left arch. He massages his foot. Most wounds heal. He laces up his shoes.

There are sounds from the trail. Others are coming up the lower fork. It’s plump Marie, glistening in her nylon running suit, and a dull accountant whose name he can never remember.

“Been swimming, I see,” the accountant says. “Where’s Elaine?”

“She swam up to the back falls with Terrill.”

“Didn’t you try it?” asks Marie.

“I’m going to hike on up,” Rob says. “Up towards the reservation. Maybe I’ll be able to see them from the cliffs.” He doesn’t think of this until the instant he’s said it. “Besides, I want to see Moony Falls.”

Marie is shedding her shoes as he starts out on the upper fork. He pauses on the cliff side and looks down over the pool. He can’t see the narrow passageway to the upper falls from here. The gravel slides under his feet. He leans into the mountain. Some of the rocks look and feel as hard as the side of a skyscraper, some crumble like rotten wood. All are dry, hot, and old, so old they obliterate the possibility of belief. And yet for centuries the men who walked this wilderness believed.

He hears a shout and looks down at the bank where he had pulled himself out of the pool. Marie is sitting there, embracing herself with her arms. “It’s too cold,” she yells. She has on a swimming suit top or a dark blue bra, he can’t tell which. Her skin is pink, burning.

“And too deep,” he shouts down. “And too wet.” He turns back to the faint trail. A lizard skitters into a creosote bush. A thin-ridged print points the way, maybe, who knows, to Paradise.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue