Articles/Essays – Volume 18, No. 4

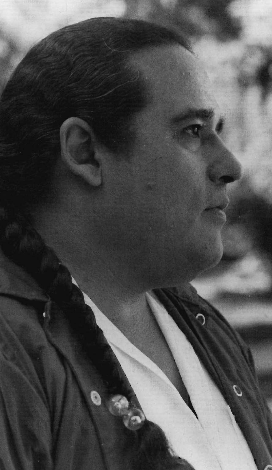

Helen John: The Beginnings of Indian Placement

My grandchild, the whites have many things which we Navajos need. But we cannot get them. It is as though the whites were in a grassy canyon and there they have wagons, plows, and plenty of food. We Navajos are up on the dry mesa. We can hear them talking but we cannot get them. My grandchild, education is the ladder. Tell our people to take it. (Manuelito, c 1880).

Perhaps others than Helen John, Amy Avery, Golden and Thelma Buchanan, and Spencer W. Kimball might have compounded an equally powerful scheme for blessing the lives of Indians, but to these individuals fell that lot. Thousands of other participants have also made great contribution, in many cases at even greater personal sacrifice, but the Indian Placement story begins with Helen. This story is based on oral histories I made with her, Amy Avery, and Heber and Fay Woolsey. They have joined the oral histories of Golden and Thelma Buchanan made by William G. Hartley in the Church Historical Department Archives. It is the story of a beginning.

***

Helen had grown up on the Navajo reservation in Arizona, the third child of Rose Toucha and Willie John’s thirteen children. Her great-grandfather had been born about 1855 and had hidden with his people in Canyon de Chelly when the American cavalry under Christopher (Kit) Carson in 1863, in an effort to subdue the Navajo, trampled their corn and burned 5,000 peach trees. Locke reports tales that survived three generations of their suffering. One pregnant woman had frozen to death during the flight. Another son held his own father as he died of gunshot wounds. Some women smothered their babies, rather than have them starve. When the Indians finally began sur rendering at Fort Wingate, about a hundred from one group of about 1,500 died of dysentery from the weevil-infested flour. The rest were herded out and started on the “Long Walk” to Bosque Redondo, about 300 miles away in East Central New Mexico. Others had preceded them. Many more would follow. Those who were ill were shot by the soldiers or abandoned. One survivor reported seeing his uncle, abandoned by the side of the road when he was too weak to go on, with a small bag of provisions. Some of the New Mexican soldiers stole some of the children and sold them as slaves.

In the four years that they were at Bosque Redondo, grubbing out mesquite with their hands for firewood, outbreaks of smallpox, measles, and other diseases killed, by some accounts, more than half of the approximately 65,000 Navajos and drought and cutworms destroyed their crops. Exhausted from starvation and discouragement, they had to be driven to the fields at gunpoint. The Comanches raided the settlements for livestock and slaves, and the soldiers did not protect them until some of the young men, dressed like Comanches, attacked Fort Sumner and killed some soldiers. Helen’s great-grandmother, who was in her early teens, escaped from Bosque Redondo alone and made her way back home where a Navajo family that had escaped the sweep took her in.

General William Tecumseh Sherman of Civil War fame, visiting Bosque Redondo after the Civil War, responded to the tears and pleas that the starving people be allowed to return to their sacred land. “When we reached Albuquerque, we could see the top of the sacred mountain we called Tsotsil and the old people were overwhelmed with joy. Even the soldiers celebrated our happiness,” the old people said. Helen’s great-grandmother was reunited with her family.

Helen remembers hiding as a six-year-old with eight-year-old Bertha when their mother spotted cars on the highway a few miles from their hogan because Indian agency officials in the 1930s were physically removing children from their families to send to government schools at various locations in the West. Helen’s uncle Clarence had, at the age of twelve, been taken from his herd of sheep and sent to the Phoenix Indian Boarding School. No one told his parents. They did not see him for five years and then he did not wish to return.

That same year, in the summer of 1935, Helen remembers her mother’s despair when the Indian agent reduced the number of their sheep to a size that would not deplete the overgrazed range. With only a few sheep, the family was reduced to poverty and her parents voluntarily brought Helen to the government boarding school at Tuba City. She stayed there nine months without being allowed to go home or to have visitors. Children caught speaking Navajo were punished. Helen, with a patient teacher whom she was anxious to please, made good progress.

In all, she attended the school five years with one year off when she was nine and in a hospital recovering from a heart condition. Then when she was almost twelve, her parents decided Helen should stay home and learn cooking and weaving while one of the younger children took her place.

Helen had grown up in poverty, remembering at the age of sixteen going shopping for a week’s groceries for under $5 and being overwhelmed when the customer ahead of her bought almost $40 worth of groceries. She heard the disparaging comments about “squaws” from white people in Richfield where her family had come to thin sugar beets and deeply sensed the discrimination and poverty of her life. Did God care about them? Had they been abandoned?

When she asked her father for permission to attend school in the spring of 1947 when she was seventeen, Willie John told her gruffly, “You ought to be happy with your life, Helen. Be proud you are a Navajo. You don’t need any more of the Bilagaanas’ education. Besides Ruth needs to go to school. It’s her turn. I can’t have you both away leaving the rest of us to do all the work. Don’t talk to me about it again.”

Frustrated and angry, Helen ran across the fields to get away and sought shelter from the hot sun on the porch of a farm house. Amy Avery, the wife of the farmer for whom Helen’s family was working at Venice near Richfield, had been in bed suffering from undulant fever. She heard Helen’s uncontrollable sobs and, concerned, persuaded Helen to tell her the problem.

“Why don’t you pray about it?” Amy asked.

“I can’t,” Helen wept. “We lost our God a long time ago.” She wiped away her tears with her sleeve.

“Well, if you’ll come in and kneel down by the couch and pray for me to get better,” offered Amy, “I’ll pray for you to get to go to school.”

The two women knelt by the couch. “What’s your name?” inquired Amy.

“Helen Rose John,” replied Helen.

“Being as you’re the guest here, I’ll pray first,” said Amy. “Dear Heavenly Father, this here Lamanite girl—

What’s a Lamanite? Helen thought. It must be me.

“—is kneeling here with me to ask a special blessing. She has been told by her father that she can’t go to school because one of her many brothers and sisters needs to take a turn. Now, dear Father, please smile down on this girl, one of your beloved Lamanite daughters. Open up the way that the desires of her heart will be fulfilled. In the blessed name of Jesus Christ, Amen.”

Turning to Helen Amy said, “My part of the bargain is done. Now it’s your turn.” Helen froze. “Lands alive, child,” exclaimed Amy after a long pause. “I bet you haven’t prayed in English before. Go ahead and pray in your own language.”

Still confused, Helen began to pray in Navajo: “Oh God, if you are there and care to help, please help me to go to school and help this Bilagaana woman to get well.” She couldn’t think of anything else to say so she stood up, helping Amy to her bed. “Thank you, dear,” said Amy, “Well, we done our part. Now it’s up to the good Lord. Would you please walk out to the mailbox by the road and fetch my mail for me? I just don’t think I could take walking out there and back.” Helen obeyed and Amy, looking through the bundle, pulled out one from the stake president. She read through the two-paragraph letter, gasped, and said to Helen, “Well, honey, the Lord never ceases to amaze me as to how fast he works.”

She walked to the telephone on her kitchen wall and gave the crank two turns.

“Operator, please ring Golden Buchanan’s office number in Richfield. Thank you. Oh hello, Golden, this is Amy Avery. We just got a letter from our good stake president and in it he informed us that you have been appointed stake coordinator of Lamanite affairs. Well, I’ve got a case for you to coordinate. I’ve got a Navajo girl in my home right now that I think would like to go to school here and learn more about our people.”

Helen went back to work. She sensed that she had an ally. The next week, Amy invited Helen and her family to the home for dinner. Helen arrived with eleven brothers and sisters.

In they trouped, smiling but shy, all dressed in dirty field clothes. Amy had instructed her children beforehand, “Pay you no mind how they are dressed or how they may act.” As she watched them walk into the house across the carpet and into the family room with their muddy shoes she tried hard to convince herself that she was prepared to face this.

The evening was well planned: Supper, popping popcorn, pulling taffy. Helen had never seen her brothers and sisters enjoy themselves so much. It pleased her that Amy was so accepting of the children, dirty clothes, muddy shoes, and all. Despite this Helen felt that the Averys no doubt had had enough of dirty Indians and that this would be the last time she ever visited them. Amy surprised Helen by inviting her and Bertha over for the following Monday afternoon. “Bring your two older brothers along, too, to give my boys some company,” she added.

When the four John children arrived that afternoon, Amy sent her boys out with Helen’s two brothers to ride horses. Amy, her daughters Marva and Wanda, spent the afternoon in the dining room sewing Indian skirts with Helen and Ruth.

During the afternoon, Helen bluntly asked Amy, “Could you teach me to read real good?”

Amy replied, “Well, Helen dear, as you know I’m not a school teacher and so I couldn’t help you much, but I’ve got a friend by the name of Lula Carson who is one. I bet she could help you. Why don’t I try to get Lula to come over here to find out just how much you know about reading so she could suggest at which level you should start. Here, take these other two pieces and see if you can sew them together on the machine.” Amy pointed out how it should be done, then left the room saying, “I’ll go give Lula a call.”

After making the call Amy returned and sat down next to Helen as she used the sewing machine. As Helen worked carefully at the project, Amy patiently gave her pointers. Amy appreciated how fast Helen picked up new skills. In about fifteen minutes a knock was heard at the door. “Come in, Lula,” called Amy. Lula was a pleasant woman in glasses who, like Amy, smiled warmly while talking. She had Helen read for her, determined that she was about second-grade level, and loaned her about a dozen readers. “Now you take them all home with you and practice reading them. When you don’t know a word and can’t figure it out you can ask either Amy or me.”

That night Helen lugged her newly acquired readers back to the tent, feel ing that she made a good start on her way back to school.

A few days later, Amy and another woman came to the John tent. Amy explained to Helen and her family, with Helen as the interpreter, that she was serving as a stake missionary for her Church and wanted to deliver a message to all of them. Promised in her patriarchal blessing that she would serve the Lamanites, Amy felt a special responsibility to tell Helen and her family about the gospel.

Amy, speaking slowly so Helen could interpret accurately, told them about the appearance of the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith. Helen had to stop her from time to time to clarify what she meant. All this was so new to Helen. Amy also explained how an angel named Moroni showed Joseph Smith gold plates on which was written the sacred history of the ancestors of the Indian people. Because Helen had to listen carefully to translate it, she had to pay close attention to all that Amy was saying. She found herself becoming very interested and felt a warm feeling in her heart. It seemed that somehow Amy’s stories were familiar.

When the family went back to their home in Moenavi, Arizona, for the summer, Amy and Helen corresponded. Amy wrote almost once a week telling her about the Book of Mormon. Helen diligently read the books Amy sent her about the Book of Mormon and also spent time every day reading and re reading Lula Carson’s second-grade readers.

In the last letter Helen wrote to Amy before returning to Richfield to help with the beet harvest she said:

I have think much bout things you write to me. I like hearing bout golden plates and Book of Mormon. You know, I want to learn a lot bout all that and other things, but as you know I only read on second grade level. I want very much now go back to school and learn read better. I want to understand more. I have decided for sure go back school. I don’t know where I go. There aren’t many schools open down here since war. Even though my father says, no, I will go to school.

I come back to Richfield to top beets in the Fall because my family depends on me to help. I see all of you then. I’ll go to school after we finish. Please give big hello to Marva and Carla and Wanda and to the boys.

Love, Your friend,

Helen

The family returned in October 1947. It was with a sense of mission—even destiny—that Helen took the path across the beet field, across the irrigation ditches and over to the Avery’s now-familiar white house. It was as if a vast horde of spirits went with her. There was Great-grandfather. Great grandmother walked arm in arm with him. There was the father who had died in his son’s arms, the uncle, left behind to die on the Long Walk, the pregnant aunt, the little children who had died of malnutrition in the hospital, Manuelito, the Navajo headman who had instructed his people to get an education, Narbona, the beloved leader, Barboncito the eloquent headman who had persuaded General Sherman in the Bosque Redondo to let his people return, and ancient ones Helen had heard about only from Amy: Fathers Lehi, Nephi, Alma, Samuel, and others, their women with them. Countless others followed, distant shadows.

The innumerable host that followed Helen up that path to the Avery home that day was perhaps only our illusion, but there was something to it. She was not taking this walk alone.

She told the warmly welcoming Amy, “I’ve made up my mind to attend school here in Richfield with Carla and Marva. I want to pitch a tent in your back yard to stay in.”

Amy gasped. “Helen, dear, we wouldn’t expect even our sheep dog to stay out there in the cold.”

“I’m used to living in tents and cold winters don’t bother me.”

“We just couldn’t let you stay out there in a tent, regardless of what you say. You’d freeze for sure, child. We would want you to stay right here in the house with us as a part of our family, but darn it we’ve got a bad space problem. With only two bedrooms all five of the children are in the same bedroom. We’ve got the boys half of the room divided from the girls side by a cardboard divider, suspended from the ceiling.”

“Oh, Mother, we could make room for Helen. We could put another bed in our half of the room,” interrupted Carla.

Amy shook her head. “As much as I’d like to, we just can’t. With just one bedroom for all six of you, it just wouldn’t work.”

Looking directly at Helen and holding her hand Amy said, “Helen, honey, somehow, some way we’re going to find a way for you to stay in Richfield to go to school. We’re sorry it can’t be here.” Tears were glistening on Amy’s cheeks.

Amy called Golden Buchanan again.

As long as he could remember, Golden had felt kinship for Lamanites. He had been raised close to them in Glendale, near Richfield, and they had visited in his home often as he grew up. Now as a member of the Sevier Stake presidency assigned to coordinate Lamanite matters he felt keenly his new responsibility to urge members of the stake that hired Navajos to improve their housing and working conditions. He admired the Averys whose concern about their Indian help was limited by their funds. “When Lincoln and his boys work side by side with their Navajo field hands you know their hearts are in the right place,” he mused. “They don’t act like they are better than them. But what to do about Helen?”

That night Golden couldn’t sleep. Lying in bed, he thought “Isn’t it some thing, while all of us who live here in this valley have so much—homes, jobs, all the necessities and more—this girl and her people, descendants of some of the greatest prophets the world has ever known are lying out there in those cold tents hardly getting enough rest to do the hard work they have to do tomorrow. What do they have to eat? Probably very little. The promises made to them in the scriptures are so great, why do they have to suffer so much?” He offered a silent prayer on behalf of the Lamanites working in the valley.

Thoughts then began flowing freely into Golden’s mind one after the other. It didn’t seem to him a vision, but it was as if his mind had expanded, allowing him to see clearly the whole range of possibilities.

“We can find someone to take this girl in and even dozens and hundreds and even more families will be willing to take other Indians into their homes. They could live in LDS homes and be treated exactly as sons and daughters. Not only would they be trained in scholastic affairs in the schools, they would learn to keep house, tend to a family, learn to manage a house and a farm. The boys could learn to work on the farms and learn to operate modern machinery. If they live in the homes of stake presidents, Relief Society presidents, bishops, and other leaders they could see the Church at work and learn the blessings of service to God and fellow men. I can see them going on missions, attending and graduating from college. After all this training what an immense help they would be to their people! They could teach their own people by precept and example all they had learned from the Latter-day Saints. This ought to cut down the time it takes to restore this people to their former blessings by a generation or two.” The whole idea grew in its dimensions the more he thought.

Golden got up quietly so as not to awaken Thelma, went into his den, turned on the light and began writing a letter. He was aware that President George Albert Smith, concerned that the Church was not doing enough for the descendants of Father Lehi, had assigned a new apostle, Elder Spencer W. Kimball, to work with Elder Matthew Cowley to develop the work of the Church among the Lamanites. To Elder Kimball, Golden wrote, outlining all the thoughts that had just come to him so clearly. The next day he mailed it.

Two days later, a short, pleasant man knocked on the door and introduced himself as Spencer Kimball. He apologized “for dropping in on you like this. I just drove up here from Arizona where I was on Church business and I’m here now for the South Sevier stake conference. I wanted to visit with you, however, before going on to Monroe.”

Hearing that he had come from the south rather than from Salt Lake relieved Golden who was feeling presumptuous for suggesting a new Church program.

During dinner, Golden described the stake project to improve living conditions among the Indians. Elder Kimball had not heard about it. After dinner, they moved to the living room. Elder Kimball explained that he had had his secretary read Golden’s letter to him over the phone. Golden had not mentioned the letter to his wife Thelma nor had he described the program he had suggested.

“I’ve come to ask you to take this girl, Helen, into your home. I would want you to take her as a daughter and sister. I wouldn’t want you to take her in as a servant nor as a guest. I would want you to consider her as your own girl.”

Golden looked at Thelma. She looked utterly shocked. Golden explained, “Sister Buchanan has found it hard to like the Indians, Elder Kimball. She had a couple of experiences with them as a little girl in which she was severely frightened.”

“Golden, that’s not completely true,” interrupted Thelma. “Elder Kim ball, frankly, if the truth were known I wasn’t half as frightened then as I am right this minute. Many of our friends just don’t like the Indians and if we were to take one into our home there would be no end to their cutting remarks. Besides, we’ve just raised boys and I don’t think I’d know how to raise a teen age girl.”

Theirtwo unmarried sons were present. Thayne, observed, “Being as I’m going on my mission in a few weeks it won’t really make any difference to me. If you want to keep her it’s okay with me.”

Without waiting to be asked, Dick spoke up, “It isn’t okay with me. If you bring her here, just consider that I’m leaving because I won’t be teased and kidded about having an Indian sister.”

Golden was speechless. Elder Kimball said, “Well, that’s fine. You think and pray about it tonight. We can talk about it again in the morning.”

Thelma was so upset she was almost in tears and prayed so long Golden finally drifted off to sleep. She pled, worried, and pled again. She felt no peace. After more than an hour, she tried unsuccessfully to sleep. Then she prayed again. She repeated the pattern for hours.

As she continued to pray she thought about the covenants she had made in the temple. She recalled clearly her covenant to give of all her means, time, and talents to build the kingdom of God. “Here’s an apostle whose major concern it is to lead out in the building of the kingdom and he has asked me to do something he feels is essential to the work,” she thought. Her mind became clear and peace, blessed peace, flowed freely into her heart. Thelma smiled contentedly.

In the morning, Thelma was frying bacon and eggs when Dick came in. Popping a small piece of bacon in his mouth, Dick said, “Mother, do you know who we have in our house? He’s an apostle. We can’t turn him down.”

“Son, I agree with you,” said Thelma. “I’ve thought and prayed most of the night and now I know it’s right to take her in, but I’ll need your support.”

“You’ll have it, Mother.”

When the family told Elder Kimball its decision, he was pleased but not surprised. “You should know,” he said, “although I believe this is the beginning of something important, you can’t expect any help from the Church, not even sympathy from the Brethren. This is because this is not a Church pro gram, but only something I would like to see tried out. Nonetheless, I can see a great future for the little start you are about to make.”

As he watched Elder Kimball drive down the road toward his conference assignment, Golden sighed. “Well, I’d better get started.”

The first snow of the season fell that night and, with dawn, the temperature had plummeted to well below freezing. All was white except a muddy twenty five-yard stretch of sugar beet field where Helen, Bertha, their oldest brother. Spencer, and their aunt, Mable, had been digging, topping, and stacking beets.

Had the ground not frozen, they could have easily jerked the beets up with the hooked tips of their beet knives. Instead they had to dig the frozen dirt away from each beet with the tips of their knives. They were soaking wet, covered with mud, and exhausted. They had spent the night on the wet floor of an old army tent, trying to keep warm with only wet railroad ties for fuel.

During a brief rest, the usually cheerful Mable was quiet, then broke out, “Why do we do this? Why do we work so hard? Look at the farmer that owns this beet field. All he does is sit on that tractor of his and plow the field and here we sit, in the mud!” Mable turned to Helen. “Helen, why don’t you go to school, get some education and buy yourself a tractor!” They all laughed. Even Helen.

The rest break came to an end. Forcing themselves to their feet, the four Navajo field hands sloshed through the mud to where they had left off digging and topping beets. They swung into action, moving as fast as the cold air and their aching muscles would let them.

As they reached the mid-point of the field, they all turned around so as to work back along unharvested rows toward the head of the field. “Look, there’s a Bilagaana at the end of the field. He’s been looking in our tent.”

It was Golden Buchanan. He began walking out across the mud, taking care to keep his balance. He didn’t want to look ridiculous by slipping and falling. As he worked his way toward them he worried, “After all of Elder Kimball’s efforts to get us to take this girl and what if she should decide she didn’t want to live with us? It would be awful tough for anyone to leave their family and move in with absolute strangers. I don’t think I’ll tell her that it will be my family with whom she will be living. It might frighten her if I tell her. I’ll let Amy tell her.”

As he stepped up to the four, Golden thought, I’ve never seen muddier people in all my life. How do they keep working in all this mud?

“Which one of you is Helen John?” Helen ducked her head and the other three nodded in her direction. “Miss John, I’ve been told that you would like to stay with a family here in Richfield and attend school. It will be possible for you to stay. All the arrangements have been made. Do you want to do this?”

Helen’s voice did not waver, “I want to stay and go to school.”

***

The first attempts at rapport between Thelma and Helen were anxious and awkward, though they were both trying hard. After just a few days, Helen disappeared, taking her clothes with her. They had no idea where she had gone and supposed she had gone back to the reservation. Not to be deterred from the work Elder Kimball had given them, Golden and Thelma arranged placements of several other Navajo children who wanted to attend school, all relatives of Helen’s. They took a teenager named Johnny Kaibetoni, who insisted on staying in Richfield when his family returned to the reservation. He was very easy to have in the home. He worked at the Buchanans’ feed and grain mill with Golden and did exceptionally well.

About Christmas time a letter arrived from Helen, postmarked Cedar City.

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Buchanan,

I had to leave your home because my family needed me to go to Enterprise to talk for them and help make arrangements to dig potatoes there.

We are now snowed in here in Cedar City. The government bus will take my family and relatives back to Arizona as soon as the weather clears up which may be tomorrow. We are out of money. Could you send me a bus ticket to Richfield so I can come back to your home? Just send to me in care of the Bus depot here.

Love, Helen

The Buchanans sent the ticket. Helen arrived, bringing with her two Navajo girls who also wanted to go to school. These two girls could speak no English, and the Buchanans knew that the obstacle was too great. They sent the girls home to Arizona.

Johnny was placed with another family and Helen began living with the Buchanans. Although communication was difficult and Helen would cry in her room from homesickness, they were all determined to make it a successful experience. Thelma marveled at how fast Helen learned housekeeping. She became so efficient that she took over most of the housework, doing one-third of the house on Thursday, one-third on Friday, and the remaining one-third on Saturday, after which she would go to the movies. Helen was very thorough and completely reliable.

Helen, enrolled in the seventh grade, did very well in reading, math, and art. Her school teachers were very encouraged by her abilities and attitude and went out of their way to help her. She won several prizes for outstanding art work.

Golden and Thelma Buchanan became her second parents. She took les sons from Faye Woolsey who was assigned by the stake presidency to teach Helen the gospel. Faye’s husband, Heber, a young seminary teacher, baptized her.

Then in 1949 when Helen was nineteen, the Buchanans took in Helen’s younger sister, Ruth. She had been in school and, though younger than Helen, was more advanced in her skills. This was too much for Helen’s pride and she dropped out of school. She did not, however, leave the Buchanan home.

Golden was called as coordinator of Indian Affairs in the stakes, serving under Elder Kimball and the Lamanite Committee. They all moved to Salt Lake City and Helen entered beauty school. When Golden was called as president of the Southwest Indian Mission, with headquarters in Gallup, New Mexico, Helen stayed in the home of Spencer and Camilla Kimball while she finished obtaining her Utah beauty operator’s license. She then joined the Buchanans in Gallup and obtained a New Mexico license. She worked for two years and during that time met Kenneth Woolsey Hall, one of her foster father’s missionaries. After she herself filled a successful mission in Kenneth’s mission, they were married in 1957 in the Salt Lake Temple. Elder Kimball had consented to perform the ceremony, but could not because he was undergoing a throat operation.

They had four daughters. Helen was a full-time mother while Kenneth worked many years at Hill Air Force Base making rubber parts for aircraft. Both have been active in the Church all their married lives. Ken is presently serving as first counselor to the bishop of the Salt Lake Fifth Ward (Indian Ward) in the Salt Lake Wells Stake. Helen is serving as second counselor in their ward Relief Society presidency and teaches a Relief Society class. Helen, at age fifty, graduated along with her husband, whom she helped in his studies because of a hearing problem, from night school at South High School in Salt Lake City in 1979. One daughter has graduated from BYU. Two are married and will graduate with their husbands. The fourth is engaged and also attending BYU. Three of them have filled missions for the Church and all four are active in the Church.

Although Helen achieved at a high personal level, perhaps her greatest achievement was serving as the catalyst for the Indian Student Placement Pro gram of the Church. After seven years of careful nurturing by Elder Spencer W. Kimball, then chairman of the Church Indian committee, and those that worked with him, the experiment begun in Richfield was declared an official program of the Church. Miles Jensen of Gunnison, Utah, a sugar mill employee who took several Indians into his own home the year after Helen had come to the Buchanans, became a full-time employee of the Church. He did much to build the program and remained in that work until his retirement in 1980. Miles Jensen was only one of many other Latter-day Saints living in South Central Utah who rallied to support the fledgling program by taking Indian children into their homes. Where Indian children had been generally ostracized before, as members of Latter-day Saint homes, they now found themselves the center of attention with other children vying for their friendship.

After its official adoption by the Church in 1954, the Indian Student Placement Program involved relatively small numbers until 1966. By 1980, approximately 20,000 Indian students of many different tribes had been placed in LDS foster homes under the auspices of the program. There is less need for it now with better quality schools and a stronger Church organization on the reservations. The service is no longer expanding and will soon be concentrating on only high-school-age children. Despite individual difficulties, Indian participants achieved success. One General Authority, George P. Lee, spent ten years of his life as a student in the program. And in this generation we see only the beginning of the results that may flow from the program that started with one lone girl, hungry for education.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue