Articles/Essays – Volume 38, No. 2

How Many Members Are There Really? Two Censuses and the Meaning of LDS Membership in Chile and Mexico

How many members are there and what does it mean to be a member? The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints regularly publishes figures representing Church membership. If nowhere else they appear in the biennial Deseret News Church Almanac. These figures are widely cited by the Church, members, scholars, and the press. As a result, it would seem that the question of how many members there are is a relatively simple issue. The other question, what it means to be a member, would seem to be the hard one.

Yet, as we shall see, neither question is either straightforward or simple. Two major countries in Latin America, Mexico and Chile, recently published decennial census numbers that included specific religious identifications. Both countries required their inhabitants to identify their religious membership as part of the regular process of enumerating national populations. In the past, these numbers have been grouped in large categories, such as Catholic, Evangelical, and Other. Many scholars have scratched their heads trying to figure out where Latter-day Saints might be classified in that set. In their most recent censuses, however, both Chile and Mexico required people to identify the specific denomination they identified with, and numbers were tabulated accordingly. For the first time, we have an independent set of figures for Church membership in the region that can be compared with the numbers supplied by the Church or explored in their own right for what insights they might give us about the population of Mormons in Latin America.

Mormons in Mexico and Chile

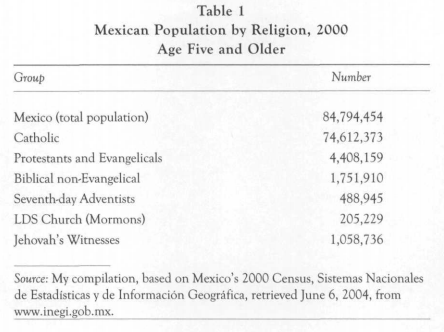

In 2000, Mexico’s census reported 205,229 Mormons five years of age and older. (See Table I.)[1] Yet for December 31, 1999, the LDS Church claimed 846,931.[2] Even if one recognizes that the census figure includes only people five and older while the Church numbers include infants and small children, the difference is astounding and raises numerous questions. These include the question of why Mexico’s official census reported only 20-25 percent as many Latter-day Saints as the Church claimed.[3]

[Editor’s Note: For Tables 1 and 2, see PDF below, pp. 55-56]

In the spring of 2003, Chile published the results of its 2002 census. (See Table 2.) For the last day of 2001, the Church claimed 520,202 members in Chile while the new census identified only 103,735 members age fifteen and older.[4] Again the variance is stunning. After accounting for the difference in ages covered, the census reports about 25 percent the number of Mormons that the Church claims.

In the case of Mexico, it was possible to speak of an isolated instance of discrepancy; but now that Chile presents a similar discrepancy, we face a pattern established by two points of data from widely different areas. The discrepancy requires that students of Mormonism think deeply about numbers and the meaning of membership.

Comparison with Other Denominations

As an initial approach to the problem, we might ask how the published numbers of other denominations fare in relationship to the census numbers. In other words, is this solely a discrepancy between LDS numbers and the censuses, or do other groups also show a similar pattern of discrepancies between their internal numeration and the census reports?

In both Mexico and Chile, it is difficult to separate numbers for the broad range of Protestant denominations. However, groups that most scholars of religion within Latin America label as “Para-Christian” or “Eschatological” (i.e., the Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Seventh-day Adventists) are tallied separately from the numbers for other non-Catholic Christians in Mexico. In Chile the Seventh-day Adventists are aggregated with the Evangelicals while the Jehovah’s Witnesses are separated. Since both the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Seventh-day Adventists accumulate and publish membership figures regularly, it is useful to observe how their figures fare compared with those garnered by the censuses.[5] Interestingly, both denominations are often cited as relatively similar to the LDS Church both in size and in rates of growth around the world.[6]

For 2000 the Adventists claimed a membership of 524,207 in Mexico.[7] The Mexican census reported 488,945 Adventists in the country.[8] The numbers are more than 90 percent the same. Likewise, the census claims that 1,057,736 Mexicans self-report as Jehovah’s Witnesses.[9] This religious body has been very successful within Mexico, far more successful than the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To compare this number with statistics published by the Watchtower Society is not quite so simple as for the Mormons and Adventists.[10] The Watchtower Society reported two membership figures for 2000: (1) the Peak Number of Witnesses, 542,117; and (2) annual Memorial Attendance, 1,681,880.[11] The first is a quite restricted measure of committed members while the second records both the former and those who do not demonstrate as strong a commitment. In comparison, the Mexican census number is almost double the first figure but almost 63 percent of the latter. In other words, the census numbers fall between the two membership figures given by the Watchtower society in the annual report.

Chile recorded 119,455 Jehovah’s Witnesses in its 2002 census.[12] According to the Watchtower Society, Chile in 2002 had 67,909 “active publishers” and 156,704 attendees at the Memorial Meeting.[13] The first number is 57 percent of the census figure, while the second is 131 percent of the census figure. In other words, the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Chilean numbers show a similar relationship to the Chilean census as their Mexi can numbers do to the Mexican census. The Peak Witnesses figure is about half that of the census number while the Memorial Attendance figure is about 1.3 the size of the census number.

On the one hand, the fact that both the Mormon and Jehovah’s Witness data show similar patterns in the two censuses suggests that the censuses reflect configurations of membership that have to do with the interaction between the religious bodies and Latin American society, rather than just the vagaries of the individual census of each local society. On the other hand, the fact that the census numbers and the membership reported by the Adventists should be more than 90 percent the same suggests that part of the concern has to do with how membership is defined in the different bodies and how those formal, institutional definitions relate to people’s identities.

Census and LDS Criteria

While the census asks people to report their personal religious membership, the LDS Church bases its numbers on members of record.[14] This figure includes all people who have been baptized as well as children of record. In comparison, the LDS criteria create a much less restrictive measure than either of the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ numbers. The Witnesses prefer to report as members only those who are committed enough to regularly witness to others about the Bible—that is, to be members, they must actively “publish.” The Witnesses state: “While other religious groups count their membership by occasional or annual attendance, this figure [“peak witnesses”! reflects only those who are actively involved in the public Bible educational work.”[15]

In contrast, being blessed as a child or being baptized (that is, accepting a critical boundary ordinance) is the minimum definition required to be listed to qualify as a member for the Latter-day Saint reports.[16] There is no implication of ongoing commitment or current activity, despite the importance of “activity” for Mormon members.[17]

The census is a very different measure. Instead of being based on the document of an action (e.g., ordinance) performed—something that can be empirically observed and quantified—it is based on an individual’s or head of household’s claim of identity in response to a census schedule or census worker. When the census asks people to state their religious membership, it asks them to make a public affirmation of current religious identity. This is not the same as asking if they are religiously active. Since the census depends on this self reporting, it can be influenced by several factors widely known by scholars of religion in the area.

First, as a society Latin America is predominantly Catholic in practice and strongly Catholic in its public face. There is still significant social pressure for people to participate in Catholic rites and to claim a Catholic identity. Thus, although an individual might claim to belong to a different religious body at other times or might participate in a non-Catholic religion, on the census or in response to a government official that same individual might claim to be Catholic. He or she might fear the implications of making a public affirmation of membership other than Catholic.

Second, religious identities and their affirmation may well be con textual. What counts according to official documents as a changed state because of some ordinance may not lead to the kind of absolute identity presumed by the religious body. People claim different religious identities in different times and places and to different people. Thus, some people may claim the absolute identity of the institution while others may claim different identities in different circumstances.

Third, the main distinction in Latin America is between Catholics and Evangelicals. Despite the many arguments of Evangelical movements that Mormons and Witnesses, in particular, are not Christian and should not be confused with Evangelicals, nevertheless in popular practice, people may see little significant difference. As a result, people the Church counts as Mormons may themselves simply claim to be hermanos—that is, brothers and sisters. In popular parlance this designation is a synonym of Evangelical. Some practicing Latter-day Saints may have been counted under this label.

Fourth, people often have multiple, simultaneous religious commitments in Latin America. They simply seek what “works” for whatever interests them at the moment. Traditionally, people hold multiple devotions to different Catholic saints. And in these more religiously diverse times, it is not uncommon in Mexico to hear people speak of attending different religious bodies for different ends and different times and places. How this translates into an identity reportable on the census form is an open question.

As a result of these factors, it is difficult to simply read the census numbers as a firm measure of absolute religious identity. Instead they must be taken as an indication of how these and other factors, including those of the formal institutions, came together at the time of the census to create statements of identity that could be quantified.

A Field of Religious Activity

Both the formal LDS and the census numbers have validity for scholarship only as limited measures. Neither fully answers the question of how many real members are there or how many members are there really. These may not be answerable questions, depending as they do on absolute essences rather than the vagaries of social process. Yet the numbers do something important; they help us approach the question of the meaning of membership.

It is likely that the census numbers of Latter-day Saints, given the four factors listed above, reflect a body of strongly committed Latter-day Saints, as one type of person involved with the Mormon Church in Latin America. Nevertheless, neither census numbers nor Mormon member ship numbers refer directly to activity or commitment. Since the census requires that people make a positive affirmation of LDS identity, when there are factors that militate in favor of not claiming that identity, publicly affirming that identity indicates some sort of strong commitment. As a result, it is plausible to argue that the census numbers may refer to committed, and hence active, members, whom Douglas Davies would call “the church within the Church.”[18] This church within the Church is like the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ “Peak Witnesses” category of people who are ac tively and strongly engaged in prescribed religious behavior. As we have seen, this number of Peak Witnesses is about half of the number of people on the census who claim to be Witnesses. If this difference parallels that in Mormonism, then somewhere between 50 percent and 100 percent of the Mormons who claim that status on the census form the church within the Church and the rest at least have a strong enough commitment to Mormonism to claim the identity on the census forms.

In fact, the relationship between the census numbers and the Church numbers is similar to the fragmentary data on activity rates we have for Latin America.[19] For example, on a trip to Latin America in July and August 2003, I spoke with seven people in four different countries, representing at least four different wards. I asked them for an impression of activity rates for their wards, and the numbers ranged from around 20 to 35 percent.

Using Davies’s idea of a church within the Church, I think it useful not to conceive of membership as an absolute, singular identity. Instead it should be understood as something in process and as something in relationship with other identities and other religious activities. With this focus, the twin measures provided by the Church and the censuses lay out a religiously significant field in which this process takes place. They help us get a sense of the size of the field and the relative numbers of people in volved at the different ends.[20]

Undoubtedly the Church insists on reporting numbers that reflect only the act of inscription on the rolls of the Church based on an ordinance because it holds that the ordinance changes people categorically. Someone who is a member is not held to be the same as someone who is a nonmember. They are not treated the same. Furthermore, a former member is a third kind of person. This concept must be taken seriously by scholars as part of the Church’s understanding of the meaning of membership.

The distinction between “member” and “nonmember,” then, establishes a boundary around a significant religious field within which people of one sort work out their “salvation” and in which different kinds of Church activity are determined. I recently spoke with missionaries serving in the Santiago II Ward in El Alto de La Paz, Bolivia. They said they spend about half their time trying to activate members of the Church and half seeking new members. In the first case, they are working the field we have identified. In the second, they are attempting to bring people into it. Similarly, when members perform home teaching, visit each other, or gossip about each other, and when they speak to their nonmember friends about the gospel or provide them as references to the missionaries, they are per forming work which depends on the categories of this boundary separating the field of members (some more active, some less active, and some having left the fold) from that of nonmembers.

Official Church numbers speak to important issues of eschatology. They perform a function within the religious system far beyond that of simple propaganda or of trying to make the Church look good. Instead they define issues that to the Church are matters of sacred significance and eternal weight. They have profound moral importance and implications. They are not simple statistics, but have values far beyond their numerical status. They help define the present and the eternities.

From an external viewpoint, the official Church numbers measure those people who have had at least enough extended contact with the Church to be baptized or who were blessed as children. As a result they provide an idea of the relative impact—of this specific religious sort—the Church has had on a given society, such as Mexico or Chile. This measure can be compared with other measures, and the nature of the impact can be more deeply studied. This is another sense of the meaning of membership.

Still the official Church numbers do not begin to measure the group on which the Church is highly dependent, which Davies calls the church within the Church. According to Davies, these are the highly active, temple-attending Latter-day Saints who provide it with its organizational core.[21] They are the leaders and those who till the field of membership. Without them, this lay Church would cease to function. It is likely that the census numbers come close to representing this smaller but institutionally significant church.

Mormon Retention

This smaller church is worth paying attention to in itself. In Mexico, 205,229 persons five years of age and older went out of their way to claim the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as their primary religious identity. This is amazing. It may not sound as stupendous as a member ship of almost a million, but it announces a quarter of a million commit ted souls who made a public admission of their dedication. Such declarations are not lightly made. Nor is it easy to make such strong solidarity with a “dissident” group, as Latter-day Saints and Protestants are called in Mexico, the norm in the region.

Similarly in Chile, 103,735 persons claimed that commitment publicly. This is amazing. Within Chile, as in Mexico, families are raising their children with a primary Latter-day Saint identity. Within both countries, young people are planning on missions, and many are actually serving, within their own country and in other countries. In both countries, a dedicated cadre of returned missionaries occupies positions of leadership. Their numbers may not be as great as had been hoped, but they are substantial nonetheless.

An indication of the importance of these numbers comes from a different country. In Bolivia the 2001 census decided not to ask questions on religion, determining that the information had little political importance. But under insistent pressure from religious groups and other organizations, it agreed instead to perform a nationwide survey on religion. I do not have the data from the full survey at the moment. But Xavier Albo, a prominent Bolivian anthropologist, published a book based on the survey.[22] He does not give us numbers for Mormons in Bolivia, although they apparently are available in the survey. Nevertheless, he does list Mormons as a separate category in his charts on religious retention. Overall his data indicate that the non-Catholic religions retain a significant portion of those who identify on the census as belonging to them, despite how historically recent their growth has been in Latin America. Furthermore, his specific data on people born into a non-Catholic religion are telling. Of those born within a household claiming Mormon membership, 82 percent continued to claim that identity. In comparison, only 48 percent of those born into households claiming no religious identity held to that identity; 68 percent of those born into Holiness households continued, 72.4 percent of those born to the category of undefined non-Catholic continued in that category; 76 percent of those born Adventist remained; 81 percent of those born to families in the historic Protestant denominations continued, while Pentecostalism retained 88.9 percent of its children for their faith as adults.[23]

These numbers are significant. They indicate the strong grip these new Latin American identities have on the next generation. They are able to reproduce themselves and they have social relevance. Of these, Mor monism seems to have one of the strongest claims on its next generation in Bolivia; it is surpassed only by the Pentecostals.[24]

To the degree the Bolivian data may be similar to the situation in Mexico and Chile, they strongly indicate that the census numbers may re fer to a group of highly committed individuals and families. Unlike those for whom the four factors listed above apply, those who claim to belong to a different religion than the Catholic mainstream have a single, strong, non-Catholic identity and are willing to announce it publicly to their national officials.

Another point of importance comes from a reading of those leaving their non-Catholic denomination of birth. In all cases where the people making the change were born into households claiming a religious membership, the largest single group became Catholic. In the specific case of Mormons, more than 10 percent became Catholic. An additional 7.6 percent joined Protestant groups that were not Pentecostal, the dominant evangelical movement in Latin America. This speaks to the ongoing importance Catholicism has as a vital, vivid religious system within Latin American society. However, it also speaks to the strength with which Mormon culture and values are transferred from a convert generation to their children in ways that match those of many metropolitan Mormons. The Latter-day Saint spiritual aesthetic is substantially divergent from that of Pentecostalism, for example, and this seems to create people with little interest in Pentecostalism, even though Pentecostalism is without doubt the most important non-Catholic movement in Latin America and probably the fastest-growing, large Christian religious movement on earth.[25]

Albo’s observation also supports our thinking that those claiming Mormon identity in the census are probably the highly committed members of the church within the Church. These are the families that are most likely to strongly socialize their children into a Mormon ethos and identity.

Regional Distribution of Mormons in Latin America

Another way of approaching the meaning of membership explores the value this LDS community has in the national societies of Mexico and Chile. A beginning of an approach to this question requires that we explore the spatial distribution of these people who claimed to be Latter-day Saint for the census.[26] Once we have seen how they clump, we can pose the question of relationships to other social, political, religious, and economic processes, since these also are distributed unevenly in national space.[27] Membership takes meaning, not just in reference to the official teachings of the Church, but in conjunction with the local social worlds in which the members live.[28]

[Editor’s Note: For Table 3, see PDF below, p. 66]

Table 3 shows the spatial distribution of Mormons across the regions of large and differentiated space that is Mexico.[29] Despite belonging to the same country, each of these regions has a different ethnic makeup, a different political history, and a different political economy. Since Table 3 also shows the distribution of other non-Catholic groups, we can see how the Mormon pattern of spatial distribution compares with those of other religions. It must be noted that these distributions, while dependent on decisions concerning the use of resources by denominational leaders, lead us down the path to understanding how Mormonism finds varying social niches in different communities and how they, in turn, relate to the global Church. Seldom do religions cross all social circumstances equally. Gener ally there is a better fit with some than with others. That fit then constrains the growth of a religion elsewhere in the same society. In this paper, I shall not establish the specific connections between the regions and the growth pattern of the Church. It is enough to show the pattern, especially since the Mormon pattern is different from that of other religious groups, and to suggest that research be performed into the specific relationships between the regions’ social reality and this pattern.

In the 2000 census, the largest block of Mormons lived in or close to greater Mexico City. (See Table 3.) The largest single numbers for Latter-day Saints came from the Federal District and the state of Mexico. They alone contained more than a fifth of Mexican Mormons. When we add the nearby and highly urbanized states of Hidalgo, Puebla, and Morelos, we get more than a third of the total of Latter-day Saints in Mexico.[30] Mexico City and its environs are perhaps the largest city on earth and the most important economic, cultural, and governmental hub for the country. Thus, it provides an important context for Mormon growth, and Mormons show a distinctive relationship with this region.

It might be argued that it is natural for the Mexico City area to claim such a large percentage of Mormons since it has the largest concentration of population in the country. This region claims some 32 percent of the population of Mexico and 30 percent of the Mormons.[31] Although Mormons are slightly underrepresented in this region, the numbers are not radically dissimilar.

But the unusualness of this geographic relationship is emphasized when we look at the numbers in Table 3 for other religious groups. Mor mons stand out for how heavily Mexico City weighs in their national membership. Curiously, this makes the LDS Church somewhat similar to Catholicism (33 percent) and different from the other non-Catholic groups cited. Future work must ask why Mormons are so geographically concentrated in the Mexico City region, as opposed to other areas.

Another important geographical region in Mexico is the northern tier of states along the U.S.-Mexican border. This area is distinctive because of its proximity to the United States and its strong economic, cultural, and political influence. It is an area about which the rest of Mexico feels ambivalence because of that proximity to the Yankees. Here, again, we find almost a third of Mexican Mormons. The relative weight of Latter-day Saints in this zone is far greater than that of any other religion, with the exception of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who find almost a quarter of their members here.[32]

It is tempting to try to explain this pattern of the distribution of Mormons—65 percent of all Mexican Latter-day Saints, according to the census—in these two regions with the historical thesis. Mormonism first established itself in the valley of Mexico and the border.[33] So it would be logical to argue that this pattern continues to the present. Nevertheless, these two areas were both significant areas of Protestant growth even before the coming of Mormons.[34] As a result, the historical thesis needs careful exploration but is not adequate to completely explain this pattern of Mormon growth. The relationship between the economic power of these two zones and Mormon growth, in contrast with that of other religious groups, must also be explored.

The next third of Mexico’s Mormons is scattered over the central north, the south, and a single state: Veracruz. The state of Veracruz is known for having the historically important port city of the same name, for its oil industry, and for its historically important liberal spirit. Not only is it important for Mormons, but it holds an even greater importance for Pentecostals and Seventh-day Adventists, for whom Veracruz alone is as important or more important numerically as the Mexico City region. In short, Veracruz has been one of the major areas in Mexico for the development of alternative religious identities. At some point, researchers must ask the question of the relationship between this state, its economic structure, and these new religions, including Mormonism. They must also ask, curiously enough, why the LDS Church has not been as successful here as these other groups.

In contrast, the central north region, the most traditional and Catholic of Mexico, claimed a tenth of Latter-day Saints. This area is often considered the heartland of traditional Mexico, and it still maintains a very strong Catholic society that resists the inroads of alternative religious groups, although they are growing on the margins. This is also the area that traditionally sends a large percentage of its population to work in the United States. Other regions are now catching up with it in terms of sending immigrants.

The Mexican south is the most Indian and the most rural portion of the country. Curiously enough, this area, more than any other, demonstrates the peculiarity of the Mormon pattern in Mexico since it is the most strongly non-Catholic region in Mexico. The state of Chiapas claims the honors with only 64 percent of its population claiming to be Catholic. This is very different from the 96 percent Catholics found in the center north state of Guanajuato, the heartland of Mexican independence. The south holds 40 percent of all Mexican Pentecostals (the largest non-Catholic religion in Latin America) and holds almost 60 percent of its Seventh-day Adventists as well as a quarter of its Jehovah’s Witnesses. Mor mons simply have not done as well in this region as these three other groups. Mormons have something distinctive about them that has led to their growth elsewhere but not in this very rural and Indian area of Mexico.

To understand this pattern better, we can see how Mormons are distributed within the state of Chiapas, since it has the lowest percentage of Catholics in the country. In Chiapas the largest populations of Mormons, as well as the highest relative percentages are found in its largest cities, Tuxtla Gutierrez and Tapachula. These are at the center of two different economic zones, the coast and the inter-mountain depression. They are not in the highlands where the Zapatista rebellion is and where the large and traditional Indian population occurs, nor are they in the colonization zones near the Lacandon jungle, where Protestantism has been much more significant. Together these cities contain 64 percent of the state’s Mormons although they only have 19 percent of the state’s total population. The urban Mormons are more than three times more important for Chiapas’s total LDS population than the cities for the state as a whole. Mormons are strongly overrepresented in the larger, economically dynamic cities of the state.

Because Mormonism is so associated with the cities, it is removed from the social processes that have made Chiapas so heavily Protestant. Mormonism is almost not found in the colonization zones around the Lacandon jungle nor is it found much in the highlands, where Protestantism has been an important factor of popular organization and of dividing traditional Indian communities. Mormonism has also not been a major factor among the agricultural workers in the lowland valleys near the coast. Rather it is primarily an urban organization. Tuxtla Gutierrez, where some 33 percent of the state’s Mormons reside, is almost 80 percent Catholic, an extreme difference between it and the state’s average. Tapachula, where there are another 31 percent of the state’s Mormons is just slightly less Catholic than the state’s average, 63.21 percent versus the state’s 63.83 percent. This means that Mormonism occupies a very different social association than Protestantism. For some reason, Mormonism seems to be more strongly associated with cities that have higher relative percentages of Catholics than it is with areas of high overall religious change.

Along these lines it is useful to explore the state of Mexico. It sur rounds the Distrito Federal, in which the City of Mexico finds its center. Most of the municipios (counties) surrounding the Distrito Federal are also heavily urbanized. Yet the state has an important rural population. Peas ants from the state of Mexico have been heavily mobilized at various times in Mexico’s history, including most recently in resistance to the construction of a new international airport for the City of Mexico on rural land. Furthermore, among these peasants is found one of the earliest areas where Mormonism was established in Mexico.[35] Before the Anglo colonists arrived in Chihuahua in 1885, people from rural communities in central Mexico converted to the Church and formed enduring congregations, whose descendants have been important in the history of the Church in Mexico and among Latinos in Utah.

Some of the communities that held Mormon congregations have been heavily urbanized. For example, Chimalhuacan is now 98 percent urban. From it came the Rivera sisters who were central in the Mexican American community in Utah and whose descendants include many pillars of the Mormon Latino community of Utah. These include a mission president in Mexico who was instrumental in the negotiations for the temple in Mexico City. One of their granddaughters is married to a former vice president of the University of Utah, and their family includes the founders of some of the best-known Mexican restaurants in the Salt Lake Valley. Similarly Ozumba is 75 percent urban and Chalco is 57.4 percent urban. But Atlautla is still 100 percent rural.

Margarito Bautista came from this community. He was an important early leader of the Spanish-speaking congregation in Salt Lake City as well as in central Mexico. He became a key figure in the Third Convention movement which sought to replace Anglo leaders with Mexican figures using the Book of Mormon as a central justification.[36]

Atlautla has the highest relative percentages of its population that is Mormon in this area. Its total population is 21,027, and 1.8 percent (n = 271) persons claimed to be Mormon. Huehuetoca is another rural community with some thirty thousand persons of whom 0.5 percent (n = 176) claim to be Mormon. In short, Mormonism still shows up as statistically visible in these communities after all the years that have passed since it was started there. Such endurance suggests a strong multigenerational commitment. It is also worth noting that, despite the long historical presence of Mormonism in Atlautla, it has not spread much, either within the municipio or to surrounding zones. It has become a historical isolate, an en clave. This pattern is extremely curious and requires historical exploration.

Despite the large territory of the state of Mexico with its large rural population, Mormonism, with a very few exceptions, is absent from rural Mexico and has had little influence in the social struggles and challenges of the rural people in the state of Mexico. Instead it is very strongly located in the cities. Not surprisingly, given the overall size of its population, the largest number of Mormons in the state is found in the suburbs of the city of Mexico.

Outside of the rural communities mentioned above, the highest relative percentages of Latter-day Saints are found in the industrial corridor stretching from the boundary of the Distrito Federal northward. In fact, the highest relative percent in the district (0.63 percent in the delegation, a geographic/political division, of Gustavo Adolfo Madero) is adjacent to this corridor.[37] Again this pattern is very different from that of Protestants and other Para-Christian groups. There is something distinctively Mormon in its membership’s relationship with the corridor that concentrates large capitalist industry in Mexico City.

These are still very large neighborhoods, sometimes close to or in excess of a million people. Even though they do not relate cleanly to social economic processes, they give us a sense of how Mormonism relates to urban space. Mormonism seems to have a strongly marked affinity for this industrial corridor, something that is not evident in the other religious groups identified in the Mexican census. In it we find something that is probably critically important for understanding contemporary Mormon ism in Latin America, if this same pattern relating Mormonism to cities and to areas of strong capitalist growth holds for other countries.

Mormon Distribution in Chile

It is fortunate, therefore, that the Chilean census provides data al lowing us to see if the same pattern holds there, at the opposite extreme of Latin America. (See Table 4.) In Chile the largest single number of members is found in metropolitan Santiago, the largest city in the country. It holds almost 40 percent of the nation’s population of Mormons. This is slightly less than the percentage of the national population in greater Santiago and is equivalent to the percentage of the nation’s Catholics it contains. But the percentage of Protestants is substantially less.

In part this is because of the historical importance of Protestantism, especially Pentecostalism, in the Biobio region and Araucania. Pentecostalism began here soon after it did in the United States and has spread from here to many other countries and regions. As a result, the Biobio region claims almost a quarter of the nation’s Evangelicals, although it has only 1 percent of the nation’s population. If we add Araucania, we find fully a third of the nation’s Evangelicals but only 7.8 percent of the nation’s population. Another way of viewing the importance of this pattern is to look at the relative percentage of the region’s population claimed by the different religious groups. (See Table 5.) These two regions have a smaller percentage of their population as Catholic than other regions in the country. In this they are similar to Chiapas in Mexico. Almost 30 percent of Biobio and 24 percent of Araucania are Evangelical. Both the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Mormons show a different distribution. Neither has equivalent strength in this region. Instead their strength, as a relative percentage of the region’s population is elsewhere.

[Editor’s Note: For Tables 4, 5, and 6 see PDF below, pp. 73-75]

Unfortunately the census does not contain the kind of detail that would allow an analysis for Chiapas similar to the analysis we made for Biobio and Araucania, so the question of how Mormonism relates to the geographical space of these regions remains to be researched.

The next largest concentration of Mormons is found in the Valparaiso region. This is the important port city at which Parley P. Pratt arrived in 1851. However, there again, in terms of relative percentages, the importance of Mormonism for the region is not as great as elsewhere in the country. Mormonism seems to have had its greatest impact on the populations of the extreme north and the extreme south. This pattern is different from that of any other religious group and requires consideration.

One way of approaching this distribution is to note that the north and the extreme south are highly urbanized, like the area of Metropolitan Santiago, while Biobio and Araucania still maintain substantial rural populations among whom Protestantism has been important. It may be that Mormonism has dedicated the vast majority of its proselytizing effort to cities, unlike the Protestants but similar to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Nevertheless there may be other factors besides urbanization, that are important in this distribution of Mormons in Chile.

Fortunately Santiago is large enough that we can begin to pose this question by looking at the distribution of Mormons within it. (See Table 6.) We notice that the relative percentage of Mormons in the comuna (neighborhood) population is highest within the relatively poor, heavily migrant neighborhoods of El Bosque, La Cisterna, and Conchali, while it is lowest in the relatively rich neighborhoods of Las Condes, Nunoa, Vitacura, and Providencia. Curiously the LDS temple is located in Providencia. However, once again, the Mormon pattern is different from that of other non-Catholic religions. Not only are there far larger numbers of Evangelicals, but they find their largest relative percentages in the comunas of Cerro Navia, Lo Espejo, and San Ramon. As just one means of demonstrating the difference between these two sets of areas, we can look at rates of poverty and extreme poverty. The most highly Mormon areas average 10.8 percent poor and 3 percent extremely poor while the Evangelical areas average 18.3 percent poor and 5 percent extremely poor. The rates of extreme poverty for the most highly Mormon areas would be substantially lower were it not for the neighborhood of El Bosque whose rates are as high as the highest in the Evangelical category.

As a result, it might be useful to make another comparison using literacy rates. The areas that are most highly Latter-day Saint have an average illiteracy rate of 1.7 while those that are Evangelical have a rate of 4. It appears therefore that Mormons are found in greater numbers in areas that are less poor and more literate. This observation is consonant with what was found for Mexico, although the specific relationship with industrial production and Mormonism would have to be explored for Chile.[38] Still one must wonder which kinds of people in these various neighborhoods are becoming Mormon and how their membership relates to conditions of poverty or wealth.

Nevertheless, we have seen that the censuses demonstrate a different pattern of distribution for Latter-day Saints and other religious groups. This fact suggests a fruitful avenue of future research to adequately understand the meaning of Mormon membership within the context of Latin America.

A Strong Faith in Latin America

Another way of making sense of these numbers, by way of conclusion, is to report some observations from a six-week visit I made to Latin America in July and August 2003. On fast Sunday in August 2003, the pulpit in the chapel of the Santiago II Ward never stood vacant. The chapel looked full, with close to two hundred persons present. One after another, the people came forward, often in entire family groups, to witness they knew the Church was “true,” that the “canonical books”—the standard works—were “true,” and that Gordon B. Hinckley was a prophet of God. They located these statements in terms of vignettes from their lives. One of the most powerful moments came when a quiet, young man with a firm, square face and a shock of unruly black hair stood in his rumpled suit to announce that he had reached the end of his mission and would be returning to his home in the valley of Cochabamba. He spoke of the impact that two years of missionary service had had on him, a former engineering student at the university, and how much he cared for the members of this ward and his companion, a young man from Chile with a quick smile, and how much he would miss each and every one of the members.

Fast meeting came first, and priesthood and Relief Society classes, with the rumbling of stomachs, came last. Outside the chapel, the zone’s market, with food vendors and merchants of many other goods, spread to encompass the white building with its spire. Yet inside, the elders’ quo rum met with more than twenty persons present, mostly young returned missionaries; in the high priests quorum, ten mostly older men discussed the teachings of John Taylor. In short, Santiago II is a solid ward with a strong group of committed members.

A month earlier, I had been in Cusco, Peru, for a similarly well-attended fast and testimony meeting where the microphone was never left silent and where the chapel felt full. It is safe to say that, although official numbers are high and activity rates relatively low, there is still a large and strong cadre of Latter-day Saints in Latin America who live Mormon lives filled with experiences intelligible to Latter-day Saints throughout the Church. These people are passing their faith and their identity to their children. But at the same time that their faith is Mormon, it connects with Latin American concerns and has strong local, contextual meanings.

In Chile, I am told, wards and stakes are being consolidated in the face of low numbers. To borrow from the scriptures, “many are called but few are chosen” (Matt. 22:14). Nevertheless, when one sums up those who appear to be chosen, they are no longer few; they become many and mighty. These appear to be the people who told the census takers in Mexico and Chile that they were Latter-day Saints. They are the church within the Church and play an important role in the two fields identified by official Church figures—those of nonmembers and those of members. They share the gospel with the former and attempt to activate and fellowship the latter. In sum, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is strong and growing in Latin America.

[1] Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas, Geografia, e Informatica of Mexico, retrieved August 13, 2003, from www.inegi.gob.mx.

[2] 2001-2002 Deseret News Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2000), 359.

[3] Henri Gooren, “Analyzing LDS Growth in Guatemala: Report from a Barrio,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 33, no. 2 (Summer 2000): 97-115, argued, prior to the appearance of the census numbers, that he had found a similar discrepancy between official Church membership and effective membership. The census numbers sustain Gooren’s argument and indicate its prescience and importance.

[4] Deseret News 2003 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2002), 329; the Chilean numbers are found on the official webpage for the Chilean Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas, retrieved on August 13, 2003, from www.ine.cl.

[5] These denominations use different definitions of membership and procedures for acquiring statistics, although they all give importance to the numbers. Here the main issue is with how their numbers, whatever definitions and procedures they use, relate to the census figures. Subsequently, this paper emphasizes the meaning of membership for Latter-day Saints, although similar exploration for the other two groups is merited.

[6] See, for example, the statistics for over 4,200 religions and faith groups available August 13, 2003, at Adherents.com, http://www.adherents.com.

[7] 138th Annual Statistics Report, General Conference of the Seventh-day Adventists. Retrieved August 13, 2003, from http://www.adventist.org/ast/general_statistics.shtml.

[8] Institute Nacional de Estadistica, Geografia, e Informatica of Mexico, retrieved August 13, 2003 from www.inegi.gob.mx.

[9] Ibid.

[10] To be fair it is seldom simple to compare numbers, particularly when they count different things. The censuses and the various definitions of membership refer to different measures that are of significance to the people establishing the count. As a result, the numbers are not strictly the same. Despite these difficulties, comparison can be fruitful, when performed carefully.

[11] 2000 Worldwide Report of Statistics, retrieved July 8, 2001, from http://www.watchtower.org. The “Memorial Attendance” figure represents the number of people who attend the annual celebration of Christ’s birth, while the “Peak Witnesses” figure is a restricted category of “practicing members”—i.e., members who actively proselyte.

[12] Chile: Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas, Informacion Censo 2002, retrieved August 13, 2003 from www.ine.cl.

[13] Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania, retrieved on August 11, 2003, from www.watchtower.org/statistics/worldwide_report.htm.

[14] The various biennial editions of the Deseret News Church Almanac that I consulted provide no definition of membership that they use in creating the statis tics. Linda A. Charney, “Membership” for the Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1992), 2:887, defines membership as stem ming from the ritual of baptism, but the actual membership numbers reported in general conference and in the Almanac, according to my understanding, include the infants of Mormon parentage who are blessed as well as the numbers of baptized members.

[15] Office of Public Information of Jehovah’s Witnesses, “Membership and Publishing Statistics,” 2004, retrieved August 13, 2003, from http://www.jw-media.org/people/statistics.htm.

[16] Latter-day Saints do not provide an official definition equivalent to that of the Witnesses in any official source I am aware of, certainly not one as accessible as the Witnesses’ website. As a result, for understanding Latter-day Saint numbers, I rely on my native understanding rather than official sources. I do not have that same native grasp of what constitutes “membership” for the Witnesses.

[17] Douglas J. Davies, The Mormon Culture of Salvation (Aldershot, Eng.: Ashgate Publishing, 2000).

[18] Davies, The Mormon Culture of Salvation, 4.

[19] Tim B. Heaton, “Vital Statistics,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1992): 4:1518-36; see also David Stewart, “LDS Growth Today,” The Cumorah Project, retrieved August 13, 2003, from www.cumorah.com/report.html#activity.

[20] Charney, “Membership,” 2:887.

[21] Davies, The Mormon Culture of Salvation, 4.

[22] Xavier Albo, Una casa comun para todos: iglesias, ecumenismo, y desarrollo en Bolivia (La Paz, Bolivia: CIPCA, 2002).

[23] Ibid., 73, Chart 3.5 C.

[24] Albo’s data from Bolivia are from one small country. As a result, they are suggestive but not conclusive. Much more work in other regions needs to be done before we can speak conclusively about cross-generational retention.

[25] David Martin, Pentecostalism: The World Their Parish (London: Blackwell, 2001).

[26] The censuses provide us a beginning for that task, enabling us to identify a fit between Mormonism and local regions, from which we can intuit a relationship with social processes. Nevertheless, without substantial local ethnographies we can only start the process of exploring this question.

[27] William Roseberry, “Understanding Capitalism—Historically, Structurally, Spatially,” in Locating Capitalism in Time and Space: Global Restructuring, Politics, and Identity, edited by David Nugent (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2002), 61-79.

[28] See Ethan Yorgason’s arguments on the importance of geography for Mormonism, particularly in its core region, in his Transformation of the Mormon Culture Region (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003).

[29] This division into regions follows Felipe Vasquez, Protestantismo en Xalapa (Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico: Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz, 1991), which compares the results of the 1970 and 1980 censuses for Protestant growth in Mexico.

[30] For convenience, I added Tlaxcala to this region.

[31] This number is based on my calculation of numbers obtained from the 2000 Mexican census.

[32] For example, only 18 percent of Mexico’s Catholics are found here, according to my calculations based on census data.

[33] F. LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), chaps. 1-2.

[34] Jean-Pierre Bastian, “Las sociedades protestantes y la oposicion a Porfirio Diaz, 1877-1911,” in Protestantes, liberales y francmasones: Sociedades de ideas y modernidad en America Latina, siglo XIX, edited by Jean Pierre Bastian (Mexico D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1993), 132-64.

[35] Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, 40.

[36] Ibid., 132-68. Cf. Jorge Iber, Hispanics in the Mormon lion, 1912-1999 (College Station, Tex.: Texas A&M Press, 2000).

[37] This Mormon zone extends through the municipios of Naucalpan, Tlalnepantla, Cuautitlan Izcalli, Coacalco, Ecatepec, and Tultitlan. There are also high rates in the nearby suburb of Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl. In terms of relative per centages, according to my calculations, Coacalco has 0.65 percent, Cuautitlan Izcalli has 0.44 percent, Tlalnepantla has 0.39 percent, Tultitlan has 0.37 percent, Ecatepec has 0.32 percent, Tultepec has 0.28 percent, Cuautitlan has 0.26 per cent, and Melchor Ocampo has 0.24 percent. In the district, the delegation of G. A. Madero has 0.63 and Venustiano Carranza 0.34 percent, Tlalpan has 0.32 percent, Azcapotzalco has 0.28 percent, and Iztacalco has 0.25 percent.

[38] Evangelicals and Mormons have different patterns of distribution within Mexico City, and the poorest areas have higher relative percentages of Evangelicals than of Mormons.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue