Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 2

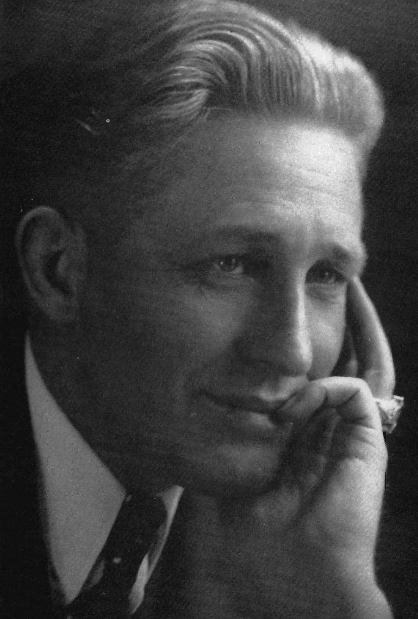

Hugh B. Brown: The Early Years

In 1969 Edwin B. Firmage taped oral history interviews with his grandfather, Hugh B. Brown. The following essay has been adapted from these memoirs, which will be published by Signature Books in 1988 as An Abundant Life: The Memoirs of Hugh B. Brown.

I was born in Granger, Utah, west of Salt Lake City, on 24 October 1883, a second son and fifth child. Like most, my first memories are of my father and mother, Homer Manley Brown and Lydia J. B. Brown. My father was the son of Homer Brown and my mother was the daughter of James S. Brown, who were not related.

My father was a large man, very independent and somewhat difficult to live with. He was a stern disciplinarian, having been raised in the old school of the pioneers. It meant little to him to chastise any of his children rather severely.

Mother, on the other hand, was kind, generous, sympathetic, and understanding. Sometimes my mother’s and father’s two natures clashed. But Mother never stood up to Father because he had a violent temper, a sharp tongue, and otherwise could be very hard to be around. Still, she was loyal to him and upheld him in many of the things he did but was heartbroken by his severe discipline and unruly temper.

Not surprisingly, the first thing I remember from my youth is my father’s harsh discipline. Sometimes my older brother Homer James (named after his father and grandfather) would be slapped to the ground while working on the garden. This also happened to me a few times. My mother’s heart would break a little each time it happened.

I would not want to leave the impression that my father was not a good man. He loved his family sincerely and did everything he could for us, but he disciplined us very severely and wanted our prompt and immediate obedience to any of his orders. Although I admired my father and loved him in a way, I never felt intimate or close to him. Even up to the time of his death, his awful temper and quick tongue alienated practically all the members of his family.

The person who influenced my early life most was, of course, my mother. She seemed to feel from the beginning that I had a destiny to fulfill. I remember her telling me many times when we talked intimately that if I would “behave myself” there was nothing I could not do, become, or have. She held that promise before me all my life. Mother was a soft-spoken yet high-spirited woman of deep faith. Her father had been a member of the Mormon Battalion and had filled seventeen missions for the Church—all of them after he had had one leg shot off. My mother’s influence, her faith in me, and her tender feelings for all of her fourteen children—seven boys and seven girls—inspired me to be and do the best that I could. I encountered many temptations in my early life, as all young boys do, but I always thought to myself, “I cannot do this and let my mother down.” In every case that I can now recall I overcame the temptation and never yielded to anything that would have in any way reflected poorly on my mother. To me she was an angel.

Next to my mother and, later, my wife, my older sister Lily had the greatest effect upon my young life. Lily was eighteen months older than I and looked upon me as her closest relative, next to our mother. Because of that trust and confidence, I went to her with most of my problems. She was something of a guardian angel to me throughout my young life, always there, pulling for me. She defended me even against my father and defied him to touch me whenever he was about to knock me down.

Both Lily and Mother would tell me that what the other boys in the family amounted to depended pretty much on what I did. I was thus made a hero to all of them. Any person who is held up before others as a leader has the responsibility to live up to what is expected. In that way my unique position in the family always kept me on guard against anything that would reflect badly upon them.

When I was about seven years old, we moved to Lake Breeze, west of Salt Lake City and north of Granger, where Father purchased fifteen acres of land and spent many long, hard days trying to turn fourteen of them into orchards. He built a very nice home and a big barn. We had cattle, horses, and other farm animals, all kinds of vegetables and small fruits, as well as the fruit trees he had planted. We lived there until I was nearly sixteen years old.

Homer, my older brother, had a great sense of humor and adventure. He got me into a lot of trouble because I had considerable confidence in him and would do anything he asked me to do. For instance, one day we were on the farm at Lake Breeze and Father had brought home a little donkey. Bud (our nickname for Homer) said to me, “Now, Dutch (his name for me because I had a hard time pronouncing r’s and g’s), you don’t ride a donkey like you ride a horse. You always get on backwards, and when you get on you lean forward and take hold of the donkey’s flank. The donkey will then know what to do.” I believed him, and he helped me on. Homer evidently neglected to instruct the donkey, as we went into a bucking spree. I turned several somersaults inthe air before landing sitting down, much amazed at what had happened.

A similar experience happened once when we saw a weasel. The little animal ran into his hole, and we got a spade and began to dig him out. We dug down quite a ways, and my brother said, “I think I can hear him down there, we are pretty close to him. Maybe you better reach in and see what he’s doing.” I rolled up my sleeve and reached down into the hole. Well, the weasel got me by the finger, and I still have a scar.

On another occasion, while we were living at Lake Breeze, the sheep men would often leave some lambs along the way between the winter and summer grazing grounds, and we would pick them up and raise them on the bottle. Bud came in one day and said, “There is a dandy lamb down in the corner of the fence. Come down and we’ll get him.” Well, I went with Bud to see this new lamb. It turned out to be a ram with crumpled horns. He had become both tired and vicious, and the sheepherder had simply decided to leave him there. Bud said, “If you will just walk up to him, take ahold of his horns, and lead him out, he will be all right.” I went up, obedient to his instructions. As I got within about ten feet of the ram he gave a loud “Baaa” and stamped his feet. I became frightened, turned to run, and fell down, leaving a perfect mark for his attack. He did not lose the chance and knocked me several feet. Bud had a good laugh over that.

So things went on between Bud and me. But I never felt any animosity or ill will towards him. It seemed to be part of my education, although he certainly had me in trouble most of the time. But the time soon came when I wanted to get even with Bud for all of his mischief. I had read a story in which a man died, was put in a big vault, and then came to life again. He got out of his casket in the night and walked around, trying to find his way out, but kept placing his hands on the faces of the other dead men around him. It was a terrible, horrifying story. I knew if I could get Bud to read it he would react as I had. So I asked him to read it. As he read and marked the book I watched him carefully. When he got to the place where the man was walking around among the dead men, Bud was very excited, to say the least.

At the time, we slept on some hay in the basement of a big barn at Lake Breeze. When Bud got to this place in the book, I said, “Leave your book now and we’ll go to bed.” He put it down reluctantly, and we went out to the barn. I pulled the barn door open. Inside it was as dark as a stack of black cats. I had previously arranged for a cousin to be in the basement in a sheet. When we opened the door and he saw this ghost standing at the bottom of the steps, Bud gave an unearthly scream and started to run. I overtook him and brought him back. “That’s just the result of the book you’ve been reading,” I said. “Don’t be so foolish. I’ll show you there’s no ghost there.” I went down the steps, felt all around, and reported no ghost.

Bud decided to trust me. He went down, got into bed, and covered up his head, but he was shaking all over. I said, “Don’t be so foolish, Bud. Uncover your head and look around you. You’ll see that there are no ghosts here.” He uncovered his head, but the ghost was standing right at the foot of his bed. He let out another unearthly scream, covered his head again, and began to pray. I felt very guilty because he told the Lord all the bad things he had done and promised never to do any more. Finally, the ghost went away. I guess Buds’ prayer had a great effect on him, as well.

When I was about fourteen years old, my family moved to Canada. Mother was heartbroken to give up her home, but Father was determined to go, and left in 1898. My brother Bud went with him, as did my sister Edna and her husband Nathan W. Tanner. (Edna and Nathan were the parents of N. Eldon Tanner, who was made an apostle in 1962 by President David O. McKay.) When my father left with Bud for Canada, he left me in charge of the farm. Although I was quite young, he said, “I expect you to take care of this land just as I have done.” I took his words very seriously and did everything in my power to make good. I think I did make good in that we raised the stock, milked the cows, fed the pigs, did the gardening, planted the crops, and harvested the fruit.

During this time, I also attended the Franklin School on 700 South and 200 West in Salt Lake City. We walked to and from school in those days. It was a long walk from 700 West to Redwood Road, especially in the cold of winter. I had to leave home just in time to get to school because there were so many chores to do in the morning. After school I had to run home as fast as possible to get the rest of the chores done in the evening. I could not play ball, marbles, tops, or any of the other games that young boys enjoy because I was the man of the house and farm.

Later, in 1899, Mother and the rest of us left for Canada by train to join Father. It was a long, tough trip that took four days. Father and some others with teams and wagons met us in Lethbridge. We loaded the furniture and our belongings into the wagons and traveled by wagon to Spring Coulee, a little village fifteen miles east of Cardston, named for a bottomless spring in the coulee that boiled up like a geyser. Our little home was built to the side of this.

When we arrived we found that the only provision for the ten of us was a two-room log house. We boys slept in tents pitched outside. The first winter was very cold and was a real trial to us city boys.

One of the things I remember was that in the fall of 1900 Father purchased one hundred small cattle, “dogies,” they were called. They were stragglers, weak, underfed, undernourished, and gave little promise. You could buy them very cheaply, which is why Father bought a hundred of them. Father shipped these hundred head of cattle from eastern Canada into Spring Coulee. The day after they arrived we had one of the heaviest snowstorms in the history of that part of the country. We had no shelter for the cattle, and we had not been able to get our hay in. The cattle were consequently turned out on the range where they seemed to want to get as far away from their owners as possible, scattering west to the Cochran Ranch and east to what later became Magrath and Raymond. Father took sick just after the cattle arrived and was in bed all winter. Mother was left in a log house with the children to care for. Most of the responsibility for the family fell on my shoulders, since Bud had said he did not want the responsibility.

Next to the Mormon colonies in Canada was the Blood Indian Reservation, one of the largest in Canada. Our cattle got over onto the reservation, and I used to ride from early morning till late at night every day, including Sunday, no matter what the weather was. It was often forty-five degrees below zero, and we would start out in the morning and sit in the saddle all day. Of course, we were well dressed, with heavy chaps and heavy felt boots, but it was still awfully cold. Any part of the body that was exposed to weather like that would freeze almost instantly. My nose, chin, cheeks, ears, and hands all froze at least once.

Two of the men I rode with, Bill Short and Bob Wallace, were especially rough. Bill was reportedly a murderer who came from Arizona to get away from the law. He later married my cousin Maud Brown. Bill was the best rider, bronco buster, calf roper, and bull dogger in the country and had to have a part in anything that was rough and tough. I remember riding up behind Bill once without him knowing that I was there and calling his name. He whirled around and faced me with a pistol in his hand. “Don’t ever do that,” he said. “I may shoot you before I have time to think.” He was that type of man. Both he and Bob made a lot of fun of me for not wishing to drink and smoke.

They had little influence on my life except that they made me more than ever determined that I did not want to follow the kind of life that had made of them the kind of men they had become. This was an impressionable time of my life, but because I came home every day to my mother, I was deter mined not to yield to temptations that beset my path.

I remember feeling at the time that I was somewhere between two futures, or epochs. I was just finishing one and starting another. I never criticized my father for having purchased those cattle, though I did think of it as a bit of bad judgment. His decision would have ordinarily been a good one, but that year the storm had caught us before we were ready.

We had been living in Spring Coulee for two years when Father realized that he must take his family somewhere to get them in school since all of us had been out of school. (I was sixteen when I went to Canada and eighteen when we moved to Cardston. I had left the Franklin School just before graduating from the eighth grade and did not go back to school in Salt Lake City until I went to the University of Utah from some pre-legal training.) We traded our land in Spring Coulee for some farms near Cardston which we boys were old enough to take care of.

I will always think of myself as Canadian. I have a great feeling for Canada. I remember being intrigued by the Mounties. They were glamorous, with their coats and hats. Becoming a Mountie was almost at the top of my ambitions, but I never took any steps in that direction. I lived thirty years in Canada, and when I returned to the United States it took me five years to become repatriated.

While isolated on the farm fifteen miles from the nearest schoolhouse, I realized that if I was ever going to amount to anything I must make it myself. Therefore, I soon obtained some books and began to read. The books that I remember most were, of course, the Bible, first, and the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants. I became well acquainted with all of them.

I knew that I had to go on a mission some day and I wanted to be pre pared, so I studied everything that I could find. I remember a little book called Reminiscences of a Mormon Missionary. This book had a great effect on my life because it told of a man in similar circumstances to my own. I read it constantly and was a voracious reader from then on.

The two books I remember best in those early days, in addition to the scriptures, were [Orison Swett Marden’s] The Secret of Achievement and When a Man’s a Man. During those lonesome days in Spring Coulee, I read these two books by lamplight in the tent, often when it was many degrees below zero. I would put on a fur coat and a fur cap and sit up at night and read.

Besides these two works, another book that touched me deeply was Archi tects of Fate, also by Orison Swett Marden. These books appealed to young men to make the best of their opportunities, and while I thought I did not have much opportunity, I was determined that for the sake of my mother, rather than for any reward that might come to me, I was going to prepare myself for future usefulness. Later on, of course, when I was in Cardston, I obtained other books and read as often as I could—books like [Plutarch’s] Lives of Illustrious Men, The Struggle of Religion and Truth, and especially Harry Emerson Fosdick’s The Meaning of Faith, The Meaning of Prayer, and The Meaning of Service.

I also had some ambition for social life, knew some girls, took some out to dances, and so on. But never during all this time did I become intimate with any girl. Never once did I do anything that I now look back upon with regret. This I attribute also to my mother’s influence.

While at Spring Coulee, we lived on a road down which all the visitors to the Alberta Stake had to pass. They ordinarily stayed at our place overnight. This is how I met Francis M. Lyman, Heber J. Grant, President Joseph F. Smith, and many other leaders of the Church. I was especially attracted to Apostle Orson F. Whitney, a great poet and magnetic speaker.

I looked upon these apostles with almost worshipful feelings and wondered if I would ever be familiar with any of them. At that time I did not anticipate what lay ahead, but I do remember that I thought if there was any way in the world to prepare myself for such a high calling, I was going to do it. With this in mind, I devoted myself assiduously to geting an education and improving myself.

My mother later purchased for me a copy of the Life of Wilford Woodruff by Mathias F. Cowley. I learned that he was a man of the farm with very little education but great faith. Anyone who came close enough to him to shake hands was impressed by his deep spirituality. He seemed to be a man who talked with God, and I held him up as an ideal. Incidentally, he was also a great friend of my father. They had adjoining farms in Salt Lake County in earlier days.

The next man that touched my life deeply was President Joseph F. Smith. He became the president of the Church in 1901 upon the death of Lorenzo Snow, who had succeeded Wilford Woodruff. With a long beard, an attractive countenance, and a bearing proud and stately, Joseph F. Smith looked like a prophet. He sat and talked to us in our home whenever he went from Lethbridge to Cardston by coach.

President Smith once talked to my three older brothers and me about his early life. He told us he had gone on a mission to Samoa when he was only fourteen years old. He told us of the struggles he had had, of his lack of educational opportunities, and of his gradual growth. He told us of an incident in his own life when he had to depend upon God and his prayers had been answered in a miraculous way. I looked upon him as a true servant of the Lord and was impressed most by his prophetic calling. He seemed to carry with him an aura of deep devotion, and when we heard him pray at night, we knew that he was talking with God. At those times I would think in my soul, “I hope someday I can talk with God as this man does.”

Of course, all men are human, and I learned later in life that even the General Authorities have faults and failings. President Smith was, in a way, a very rugged man who had been raised in the school of hard knocks. I remember, later in life, finding out that he could be very severe and exacting in his demands upon his family. But unlike my father, President Smith was also loved deeply by his family. He had several wives and was very just and fair with them. In the days of Brigham Young, with whom he had associated, the man of the house was expected to be severe and exacting and was respected for being such.

Because of my father’s attitude towards my mother and President Smith’s attitude towards his families, I made up my mind early that I would govern my own family by love and not by force. I attribute this determination, which I have followed throughout my life, to the fact that I knew men who were great and good, but who, it seemed to me, kept their families in awe and did not get close to them. When I married and had children, I intended to try to get close to each of them, as my mother had done with each of us.

I think I have succeeded fairly well in this, although there are many things that, as I look back over the past, I would like to have changed a bit. For example, I think I left too much to my lovely wife to do. I could have helped her more if I had been thoughtful enough. But, all in all, I think we raised our family in a spirit of love, for which my wife was more responsible than I.

All of the discipline in our family depended upon me, and I had enough of Father in me to exercise control. Still, in all our married life, raising eight children, I do not remember once having to give any of them a whipping. I sometimes thumped them on the head with my fingers or corrected them sternly, but I never found it necessary to use physical force, and I never did believe in whipping children. It would have broken my wife’s heart if I had.

Zina and I never had any quarrels in our lifetime, at least none that I can remember. She was a sweet, gentle spirit. Even if I believed that whatever I said was the law and testimony, we still never had any violent disagreements. Of course, we had the usual problems to face, and we tried to face them together. She has stood side by side with me through good and bad weather.

I do not hold myself up as an ideal, or as perfect, in any respect. Every man has his troubles in raising a family during the early years of his marriage and the teenage years of his children. And, like others, we had the usual amount of that. But I think we feel grateful now, as we look back and re member, that our children have nothing to regret, that neither of their parents went too far astray. They knew when I told them they had to do something, that they had to do it. I never had very much trouble getting any of them to feel this way. And I do not remember any of my children at any time will fully disobeying my orders.

I became a stake president quite early in my life, had been a bishop’s counselor, and was in the high council before that. I remember saying more than once to my own children, as did their mother, “Remember who you are” or “You must do so and so because your father is well known.” I think now that this was probably not a good thing for them. They may have felt that they were not individuals in their own right and may have looked upon me as some one removed from them because I was thirty-seven years old when I was made a stake president. Since that time they have only known me as President Brown. I am sorry to say that I have seen the effect of my possibly overbearing attitude in the lives of some of my children, who have sometimes been overly timid, fearful, pessimistic, and even depressed.

Of course, each child is different, and we have to treat them all alike by treating them differently. Some of my children have been more active in the Church through the years than others. Most have been quite active, holding positions in wards, stakes, and even on a general level. But one daughter did not want any part of the Church and has kept pretty well aloof from it. From the time she was a little girl, she resented my position and seemed to feel that I was robbing her of her birthright by not giving her enough time.

Children can easily resent their parents if they do not spend enough time with them. I tried not to neglect my family, but as I look back I realize that I did, to some extent, although I hope that I always realized that my primary responsibility was my family, my home. Now, the brethren do not all follow the same rule, but I think we are pretty much united in our feelings toward the place of the family in our public church work.

In 1904, I came down to Salt Lake City from Cardston to go on a mission to England. As I left Cardston on the train my mother was at the station to tell me goodbye. She said to me, “My boy, you are going a long ways away now and you will be on your own. Do you remember when you were a little boy you often had bad dreams? Do you remember that you would cry out in the night? Your bedroom was next to mine, and you would say, ‘Mother, are you there?’ And I would say, ‘Yes, son, I’m here, just turn over and go to sleep.’ You always did that, knowing that I was near and that you didn’t need to fear any more. Now, I’ll not be there when you arrive in England, more than five thousand miles away, across a continent and an ocean, but if you will re member God is as close to you as you will let him be, and if when any emergency arises, you will call out and say, ‘Father, are you there?’ there will come into your heart a feeling of his presence, and you will know that you have someone upon whom you can depend.”

Many, many times since then, in the ensuing sixty or more years, I have cried out and asked, “Father, are you there?” And always I have had the impression that he was mindful of me, was available to me, and would see me safely through.

When, at the beginning of my mission, I went through the Salt Lake Temple, I met Heber J. Grant, and he later helped to set me apart as a missionary. I had earlier met Elder Grant, a member of the Council of the Twelve Apostles, in Spring Coulee and in Cardston, and I believed that I knew the man pretty well.

When I arrived in England, Elder Grant was the president of the European missions, including the British Mission. In 1905, after I had been in the mission nearly one year, I had kidney stones. The pain was so severe that the local English doctors told me I must go home and have medical attention or I would die. President Grant learned of this and made a special trip from Liverpool to Norwich to tell me that I would be released and sent home. This broke my heart.

I said to him, “President Grant, if you will give me a blessing, I will not have to go home. I will get well.”

“If you have the faith that that is so,” he replied, “it will be so.” He then blessed me, and I did not have another attack of kidney stones.

This experience tied us together. He remembered it, as did I, throughout his life. As the years passed, every time I crossed the path of Heber J. Grant I felt that I was in the presence of greatness. He seemed to have a special feeling toward me and told me once that he expected great things of me. He seemed to take up the story where my mother left off. I later learned that he did not have a son, only daughters, and that this was a great source of sorrow to him. He seemed to want to adopt me in a way. In fact, when Aunt Zina, my mother-in-law, went to him after I had spoken to her about marrying her daughter, he said, “Zina, I have seven daughters of marriageable age. Hugh Brown can have any one of them he wants. That’s my answer to you as to whether or not you should let your daughter Zina marry him.”

President Grant and I thus shared a tender feeling towards each other that lasted until his death in 1945. He was responsible for my being made a stake president both in Canada and later in Salt Lake City. I attribute much of my tenacity to the stories he told of how the things we persist in doing usually become easier to do, not because the nature of the thing has changed but because our ability to do it has increased. His stories left a lasting impression upon my mind.

Later, in 1937, when I was called to preside over the British Mission, President Grant asked me to accompany him to the mission field. For five weeks I was in his presence daily as we traveled all over Europe together. I learned to love the man and to know something of his deeper nature.

Once we were on a train going from town to town, holding meetings where we could, and were pulling into Heidelberg, Germany. As the train slowed down at the railway station, we looked out the window and saw a huge crowd. We let the window down, and the people broke into singing “We Thank Thee, 0 God, for a Prophet.” They were singing in German, of course, but we knew the tune.

President Grant arose and put his head out of the window. Tears rolled down his cheeks as he looked upon those people. The train only stopped a few minutes before we pulled out again. When he sat down beside me he was still crying.

“Hugh,” he said, “I am not entitled to that kind of adulation. This is what they used to do for Brigham Young when he traveled from Salt Lake to St. George. To think they would feel that way toward me and to sing ‘We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet,’ and be referring to me. .. . I am not entitled to this.”

While he was talking he put his head in his hands and his elbows on his knees and went on talking. I thought he was talking to me for a time, but I discovered shortly that he was talking to God. He said, “O, Father, thou knowest that I am not worthy of this position, but I know that I can be made worthy, and I want to be worthy. I want thy spirit to guide me in all that I do and say.” This, to me, showed the spirit of the man—great humility and great faith, although he had weaknesses which at times seemed to overcome these admirable qualities.

Many of the people who knew President Grant thought of him chiefly as a financial man. They did not look upon him as a prophet like Joseph F. Smith. 1 had been one of these. I thought he was a great leader, but I did not feel the same towards him as I did towards President Smith. President Grant was a very tenacious businessman. In banking, in insurance, in the sugar company, and in other ways, he showed his ability as a businessman. Much of his success resulted from his tenacity to put over a deal, and in many instances, I think, he could be rather sharp. That was one of his great weaknesses—one that made it difficult for some people to support him. But I learned, and knew from the time I went to preside over the British Mission, that in addition to his financial ability, he was a prophet of God and lived very close to the Lord.

Before I presided over the British Mission, I came to Salt Lake to practice law in 1927. When I came down from Canada a question in my mind was whether I should be a Democrat or a Republican. I spoke to several people about it. President Grant at the time was an ardent Democrat, as were his counselor and cousin, Anthony W. Ivins, and B. H. Roberts. Each of these men told me at different times that if I wanted to belong to a party that represented the common people I should become a Democrat, but that if I wanted to be popular and have the adulation of others and be in touch with the wealth of the nation, I should become a Republican.

I took what these men said seriously and became a Democrat and have stayed a Democrat, even though President Grant later turned very bitter toward Franklin D. Roosevelt because he thought he was a dishonest man. President Ivins remained true to the Democratic Party, as did B. H. Roberts, Stephen L Richards, and other men and women of those times. I never found a reason to change my own political allegiance.

Later, President Grant wanted me to join the Republicans and forget the Democrats; he was rather pronounced in his denunciation of the Democrats as a whole. I had the effrontery to tell him that I thought he had turned his back completely on his own allegiance and that he should have stayed a Demo crat. We argued on this point quite a bit as we traveled over Europe. At that time, he was just changing his political allegiance, and his cousin, Anthony W. Ivins, pleaded with him to stay true to the party.

B. H. Roberts was, of course, another outstanding Democrat. Because of this, he was sometimes out of harmony with many of the other brethren, but he had the temerity to stand up for what he believed in and to suffer for it. I knew him well and was impressed with his ability as a speaker, a writer, and a leader. In my opinion, he was the greatest defender of the Church we had had up to that time. He and Orson Pratt built a case for the Church which could not be gainsaid. One of the greatest speeches he ever delivered was his disclosure to the congressional committee which was deciding whether he, as a polygamist, should retain his seat in Congress during the 1890s. He rose to great heights on that occasion. I traveled with B. H. Roberts on many occasions. He became my ideal in public speaking and contributed much to my knowledge of the gospel and to my own methods of presenting it. I owe a lot to B. H. Roberts.

I remember B. H. Roberts and John Henry Smith, who at the time was a counselor in the First Presidency, entering more than once into a powerful battle on politics. John Henry Smith was an ardent Republican. On one occasion, B. H. Roberts told him that he should wash his mouth out with soap because of the things he had said about the Democrats. John Henry replied, “I’ll wash my mouth out after you have taken some lye to your own mouth and cleansed from it some of the terrible things that the Democratic party is guilty of.” This was a battle royal between two giants. I thought that B. H. Roberts came off victorious, but, of course, my thinking on this is prejudiced.

More than ever, as I think back since I returned to the United States in 1927, I would still choose to be a Democrat rather than a Republican. I realize that by that choice I would be in the minority—almost a minority of one—among the General Authorities, since most of them are Republicans. But my conversion to the principles of the Democratic party has been complete, and as time goes on I become more and more convinced that the Democrats have the right philosophy, both in foreign policy and in their refusal to look back or to stand still. Theirs is the party of progress. I do not want to give a political speech, but I am more of a Democrat now than I ever was.

Even though he apostatized and was later excommunicated, another of the great men of the Church was John W. Taylor, the son of Church president John Taylor. He was a prophet and often made predictions that I lived to see fulfilled. For instance, he once stood on the hill where the temple now stands in Cardston, Alberta, at a time when there was just a handful of Saints there and said, “The time will come when a temple will stand on this hill. At that time, you will be able to take your breakfast in Cardston and your dinner in Salt Lake City.” That seemed like an impossible thing because it then took three days to get from. Cardston to Salt Lake City.

I was present when he made other predictions as well. He predicted the success of the Cardston Saints’ farming operations when, because of early frost, or late spring, or some other reason, it looked as though the crops would fail. He told the farmers to go ahead and plant. We once harvested the best crop we ever had in Canada after a big hailstorm when it looked as though all was lost. John W. Taylor was also a powerful speaker. He moved the people and did a lot of good, but then he got off the track. I respected this man for his life and for his devotion, but I could not agree with his opinion on polygamy.

Of those who had the greatest impact on my life, I think most immediately of Joseph F. Smith, John W. Taylor, and Heber J. Grant. But I would also like to mention someone who was not a member of the General Authorities, but a bishop of a ward in Cardston. I was his counselor, just twenty-five years old and newly married.

At this time, Bishop Dennison E. Harris was forty-five years old, and we two counselors were full of fire and needed some lessons in humility, tolerance, charity, and love. A young woman, accused of sin, was brought before us. She confessed her sin and tearfully asked for forgiveness. Bishop Harris asked her to retire to another room while we considered our verdict.

He then turned to us. “Brethren, what do you think we should do?”

“I move we cut her off from the Church,” the first counselor said.

“I second the motion,” I added.

Bishop Harris then took a long breath and said, “Brethren, there is one thing for which I am profoundly grateful, and that is that God is an old man. I would hate to be judged by you young fellows. I am not going to vote with you to cut her off from the Church. I am going out and bring her back. The worth of souls is great in the sight of the Lord.”

We did not agree with him at the time but subsequently learned that he was right. Some fifty years later I was back in Canada to hold a conference. Sitting on the stand I noticed in the audience a woman whose face had many lines and some rather deep wrinkles. Her face showed a life of hardship and struggle, but nonetheless was a face that engendered faith. I asked the president of the stake who that woman was, and he told me. I went up to her, and she told me her maiden name. She was the girl the other counselor and I had wanted to cut off from the Church.

Afterward, I asked the president what kind of a woman she was. “She is the best woman in the stake,” he said. “She has been a stake and ward president of the Relief Society. She sent four sons on missions after her husband died. She has been faithful and true all the days of her life.”

Of course, the president did not know what I knew about her, but his praise confirmed to my mind this truth: The Lord wants us to have charity and love and tolerance for our fellow men. If we forgive others, including our selves, he will forgive us. This is a lesson I have learned repeatedly throughout my life, and one I hope I will never forget.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue