Articles/Essays – Volume 33, No. 2

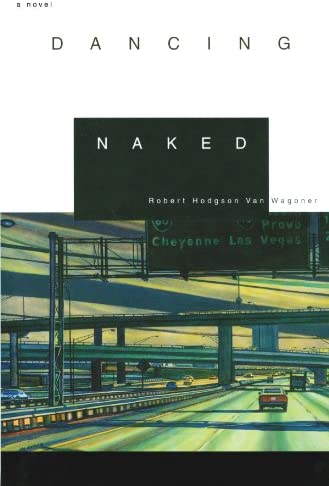

Intricate, Lucid, Generous | Robert Hodgson Van Wagoner, Dancing Naked

Few first novels in Utah in the last three decades have earned the popularity and notoriety of Dancing Naked. When Robert Hodgson Van Wagoner did a “pre-publication” reading from the book at the Writers@Work conference in July 1999, all the advance copies were sold out in one evening. After the novel’s official release, Van Wagoner did his first reading at Weber State University, his alma mater. The novel sold briskly on that occasion and thereafter during a reception hosted by the English Department where eager fans bought the book in triplicate to give away at Christmas. For days afterward, students and faculty at WSU talked about how amazing, riveting and, above all, daring the book was. Subsequently, when Dancing Naked went into a third printing and reached number one on the list of books sold in Utah, I was not surprised.

I was very surprised, however, when I attended the annual conference of the Association for Mormon Letters in February 2000. As usual, in that warm and exhilarating literary gathering, readers and critics especially sought out writers for kudos. The best novels, collections of short fiction, and poetry were discussed, not only in the foyer outside, but inside the auditorium at session-papers as well. The one thing I was acutely aware of by the end of the day was that nobody had mentioned Dancing Naked or its author! It was very unusual for the membership of AML to ignore a Mormon writer whose award-winning first novel had become the talk of the town. Was it some unarticulated fear? Or was it plain embarrassment that Van Wag oner had dealt at length with topics that exposed our deepest obsessions bordering on homophobia and moral intolerance?

Dancing Naked has not been a com forting read for most readers though it has been a compelling one. Ours is a society that indulges in make-belief as an antidote to all the genuine and imagined problems in society. If we wish to wipe out certain differences from what we think of as normal human behavior, such as homosexuality in relation to heterosexuality, we pretend that these differences do not exist or that they can and should be cured. Such moral inflexibility has brought a strong streak of intolerance into our thinking and behavior—intolerance of lifestyles, gender behaviors, and family relationships that do not conform to those traditionally held up as exemplary. Van Wagoner, in contrast, is painfully, brutally honest. At the center of Dancing Naked is protagonist Terry Walker’s intolerance of homosexuality and the psychic wounds inflicted on him by his father for Terry’s childhood proclivity for masturbating.

Terry, now a mathematics professor at the University of Utah, is given to writing weekly tirades against homosexuals which appear conveniently disguised as letters to the editor in the city’s newspaper. The novel opens with Terry discovering that his fifteen year-old son Blake has hanged himself in the bathroom with the shower faucet on full blast and the pages of a magazine featuring a gay couple in ecstasy lying open on the bathroom floor, leaving no doubt as to his sexual orientation. The discovery opens the flood gates of Terry’s anger at the disgrace, his sense of betrayal by his son, his memories of his own childhood traumas and guilt inflicted by his father, his early fixation on his mother, his resultant inability to relate to loved ones in his adult life, and finally his grief and recognition of his own role in his son’s death. How Terry deals with this tragedy becomes the fascinating unfolding of this novel.

We realize that Terry’s father was a cruel, homophobic, and bigoted man, who chastised his son at every opportunity, thus rendering him ineffectual in dealing with human relationships. While growing up, Terry tried desperately to please him, yet hated him passionately. There is even a suggestion that Terry may have married his wife Rayne just to spite his father, since his father was convinced that she, as a gen tile, was a bad influence on his son. Rayne is an aggressive wooer. She is genuine but brash, attractive but assertive. And she is a working mother. Award-winning teacher, wife, and mother, she is a liberal, especially when it comes to understanding human nature. Singular in every way, she is disturbing for the average Utah woman to accept as a role model, neither submissive nor feminine enough. Yet she is the one who holds her family together after the death of their son. All these situations add up to one complex world for a young writer to tackle. And Van Wagoner tackles it competently.

Dancing Naked is an extraordinarily well-written first novel. The writer’s apprenticeship in writing award-winning short fiction is reflected in a number of ways: development of character in short situations; enumeration of seemingly little incidents that have colossal repercussions and subtexts; development of vivid scenes that add to the cumulative effect in highlighting the drama and the trauma of life’s vicissitudes. Van Wag oner is superb at developing character. Even the two policemen who interrogate ten-year-old Mindy in chapter 2, “Coffin Shopping”—the one with wide hips and the other short, referred to as Hips and Shorter—emerge within their miniscule parts as two very different individuals with distinct personalities.

Terry Walker is a very complex character. Van Wagoner excels at flesh ing out Terry and simultaneously pro viding the novel with intellectual and philosophical ballast through a third person narrative limited to Terry’s point of view and to the workings of his mind. The novel ends up spelling out all the essentials of character and psychology, even philosophy, leaving little to the reader’s interpretive skills. Not much is left for transactional intuition or imagination. Ordinarily, such an approach may lead to a reader’s dissatisfaction. But this does not hap pen in Dancing Naked: the reader’s reward is discovering the intricate nuances of Terry’s contorted mind that has matured into a recognizable replica of his father’s. Terry holds our interest, though not our sympathies always. Van Wagoner exposes Terry’s convoluted mind with such eloquent lucidity that the book continues to fascinate the reader even on a second reading.

The narrative technique of Dancing Naked is worth noting. Written in the present tense, the narrative slips in and out of the past tense seamlessly as it swims through Terry’s memory, intellectual speculation, and current happenings. We become swimmers in the flux of Terry’s mind.

Utah readers who see the novel’s close ties to the Mormon belief system may tend to consider it an exclusively Mormon novel. Not true. Van Wagoner’s novel is neither an attack on nor a defense of Mormonism. Mormon Utah is simply its milieu. No situation that arises in the novel fails to relate to human predicaments at large or to other people in other states in the country. Terry could have lived in the Bible belt, for instance. Dancing Naked is no more only Mormon than any novel by Graham Greene is only Catholic, or any by Philip Roth only

Jewish. As a writer, one must flesh out one’s fictional world from one’s own real world. And despite Van Wagoner’s recent move to Washington State, his lifelong immediate world happens to be Mormon Utah. A preoccupation with the novel’s implicit local culture may blind us to the literary merits of the book. Michael Cunningham’s 1998 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Hours, has reminded us anew that good literature often deals with unsettling issues. What we find in all good novels, including Dancing Naked and The Hours, is the writer’s commitment to understanding human nature and to writing about it honestly without malice toward anyone.

Everyone deserves to read Dancing Naked.

Dancing Naked, by Robert Hodgson Van Wagoner (Salt Lake City: Signa ture Books, 1999) 364 pp., $20.95

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue