Articles/Essays – Volume 17, No. 2

“Is There Any Way to Escape These Difficulties?”: The Book of Mormon Studies of B.H. Roberts

Although B. H. Roberts has been characterized as a “defender of the I faith,” two of his most extensive analyses of the Book of Mormon—the 141-page “Book of Mormon Difficulties” (1921) and the 291-page “A Book of Mormon Study” (1923)—have been virtually ignored for over sixty years.[1] These provocative studies deal primarily with (1) conflicts between Book of Mormon teachings about Indian origins and archeological discoveries, (2) internal inconsistencies in the Book of Mormon, and (3) a comparison of Book of Mormon ideas with legends and beliefs popular in the area where Joseph Smith had grown up.

Since the mid-1940s, historians and apologists have debated the import of Roberts’s summary of “parallels” between the Book of Mormon and Ethan Smith’s treatise, A View of the Hebrews,[2]but only recently have Roberts’s two major studies been examined.[3] In 1979 and 1981, members of the Roberts family gave copies of these works to the University of Utah and Brigham Young University. Roberts’s two studies, with descriptive correspondence, will be published this year by the University of Illinois Press.[4]

Some students of these Roberts works have concluded that he was expressing personal doubts that had crystallized after concentrated study of the Book of Mormon. Others have seen in his work a detailed and eloquent presentation of the questions an honest investigator might reasonably have after an open-minded study of the document—a “devil’s advocate” stance. In either case, Roberts’s examinations are important to the Mormon community because the Book of Mormon has seldom received such concentrated study from a General Authority, particularly a study that isolated major issues concerning the “keystone of our religion” which remain basically unresolved today.

It is particularly important at this time when a significant segment of scholars within the Mormon community has proposed a carefully developed hypothesis that the Book of Mormon covered a geographically limited area. This hypothesis, persuasive to many, seems to be a major modification in the traditional view, beginning with Joseph Smith and his contemporaries, that both American continents were Nephite and Lamanite territory. This view is still widely held; within the last few months, the Church News identified the estimated 177 million Indians of North and South America and Polynesians as Lamanites.[5]

This essay will summarize Roberts’s two papers expressing concerns regarding Book of Mormon authenticity and his reasons for believing that the Church should deal with these questions. It will also consider where we have come in our search for answers to the questions he posed in 1922 and 1923.

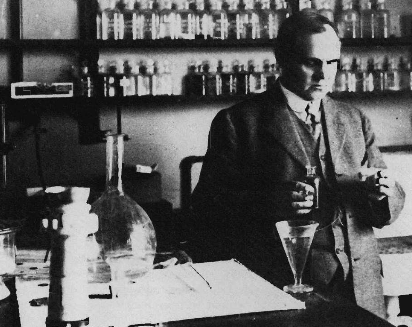

Brigham Henry Roberts (1857-1933), a General Authority of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and widely respected orator, theologian, and historian, devoted much of his life to the study, analysis, and defense of the Book of Mormon. In both his three-volume New Witnesses for God (1895, 1909) and two-volume Defense of the Faith and the Saints (1907, 1912), he developed the primary arguments used to support the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. Called at age thirty-one to the First Council of Seventy in 1888 and made its president in 1924, Roberts represented the LDS Church at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions and the 1933 World Fellowship of Faiths, both in Chicago. He also served as president of the Eastern States Mission (1922-27) and compiled two major works of Mormon history: the seven-volume History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints primarily from Joseph Smith’s records (1902-11) and the six-volume A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Century I (1930).

Thus it is not surprising that when a nonmember posed several troubling questions about the Book of Mormon in 1921, B. H. Roberts was asked to respond. Nor is it surprising that Roberts met the challenge head-on, elaborating the issues in a 141-page report, “Book of Mormon Difficulties,” which he presented to Church president Heber J. Grant and other General Authorities during an eight-hour meeting.[6]

“Book of Mormon Difficulties”

The questions came from a Mr. Couch of Washington, D.C., a scholarly friend of William E. Riter, the twenty-year-old son of a Logan, Utah, pharmacist. Prior to serving an LDS mission, Riter had asked Couch to read and criticize the Book of Mormon. Observing that languages change slowly, Couch asked Riter to explain how the language spoken by the Book of Mormon people in the fifth century A.D. could have multiplied into the several hundred distinct Indian languages spoken by the Indians in the fifteenth century A.D. Couch also questioned Book of Mormon descriptions of horses, steel, “cimeters” (Persian sabres from the 16th-18th centuries A.D.[7]), and silk—all apparently nonexistent in the pre-Columbian Americas.

On 22 August 1921, Riter sent Couch’s inquiries to author and scientist James E. Talmage of the Council of the Twelve, who passed them on to Roberts. Roberts approached the questions from many perspectives and consulted at least two friends[8] but, as his 29 December 1921 cover letter to “Book of Mormon Difficulties,” acknowledges:

. . . while knowing that some parts of my treatment of Book of Mormon problems in that work [New Witnesses for God] had not been altogether as convincing as I would have liked to have had them, I still believed that reasonable explanations could be made. . . . As I proceeded with my recent investigations, . . . I found the difficulties more serious than I had thought.

He then urged President Grant and the Council of the Twelve to continue the discussion: “I am most thoroughly convinced of the necessity of all the brethren herein addressed becoming familiar with these Book of Mormon problems, and find the answer for them, as it is a matter that will concern the faith of the youth of the Church now as also in the future.”

“Book of Mormon Difficulties,” written in three parts, was presented as an expanded study of Book of Mormon problems. By directly confronting problems and inconsistencies that careful readers might find in the Book of Mormon, Roberts evidently hoped to develop some answers that could be used in defending the LDS faith from future attacks.

In the first part of his paper, “Linguistics,” Roberts examined the difficulties arising from claims that contemporary American Indians were descended from the ancient Hebrews. In the second part (untitled), Roberts discussed the apparent absence today of domestic animals, metals, grains, and wheeled vehicles mentioned in Book of Mormon descriptions of early Nephite peoples. In the third part, “The Question of the Origin of Native American Races and Their Culture,” Roberts explored theories which traced native Americans to European, Asiatic, or Hebraic origins.

Roberts presented his report to Church leaders in an all-day meeting 4 January 1922 which continued the next day and also on 26 January.[9] At the end of that first day, James E. Talmage, an apostle, recorded:

Brother Roberts has assembled a long list of points called “difficulties,” meaning thereby what non-believers in the Book of Mormon call discrepancies between that record and the results of archaeological and other scientific investigations. As examples of these “difficulties” may be mentioned the views put forth by some living writers to the effect that no vestige of either Hebrew or Egyptian appears in the language of the American Indians, or Amerinds. Another is the positive declaration by certain writers that the horse did not exist upon the Western Continent during historic times prior to the coming of Columbus.

I know the Book of Mormon to be a true record; and many of the “difficulties” or objections as opposing critics would urge, are after all but negative in their nature. The Book of Mormon states [that Lehi] and his colony found horses upon this continent when they arrived; and therefore horses were here at that time.

According to Wesley P. Lloyd, a Brigham Young University administrator and personal friend to whom Roberts related the experience some eleven years later, the Twelve “merely one by one stood up and bore testimony to the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon,” but “no answer was available.”[10]

In a letter to President Grant five days after the 4 January meeting, Roberts expressed his disappointment over the outcome of the discussions:

There was so much said that was utterly irrelevant, and so little said, if anything at all, that was helpful in the matters at issue that I came away from the conference quite disappointed. . . . While on the difficulties of linguistics nothing was said that could result to our advantage at all or stand the analysis of enlightened criticism. . . .

I was quite disappointed in the results of our conference, but notwithstanding that I shall be most earnestly alert upon the subject of Book of Mormon difficulties, hoping for the development of new knowledge, and for new light to fall upon what has already been learned, to the vindication of what God has revealed in the Book of Mormon; but I cannot be other than painfully conscious of the fact that our means of defense, should we be vigorously attacked along the lines of Mr. Couch’s questions, are very inadequate.[11]

On 6 February 1922, about one month after his letter to President Grant, Roberts, assisted by Second Counselor Anthony Ivins, and Elders John A. Widtsoe and James E. Talmage, wrote an optimistic response to Riter that minimized the difficulties Couch had raised.[12] Roberts stated that the problem of many languages deriving from one is “not that unsolvable.” He said that oral language might change quickly and people speaking in different tongues may have come to North America during the thousand years from the end of Nephite history (A.D. 421) to the coming of Columbus (1492). Roberts also acknowledged the “possibility that other groups of people may have inhabited parts of the Americas, contemporaneously with the people chronicled in the Book of Mormon, though candor compels me to say that nothing to that effect appears in the Book of Mormon.”[13] He did not respond to Couch’s question about the lack of fossil evidence for such Book of Mormon animals as the horse.

“A Book of Mormon Study”

For Roberts, however, these concerns about Book of Mormon authenticity were far from resolved and President Grant approved a committee composed of Ivins, Talmage, Widtsoe, and Roberts to study these problems.[14] In his journal, James E. Talmage recorded meetings with Roberts in the home of James H. Moyle to discuss Book of Mormon questions through the spring of 1922.[15]

On 15 March 1923, Roberts addressed a second report, the 291-page “A Book of Mormon Study,” to President Heber J. Grant and the Quorum of the Twelve. In his cover letter, Roberts defined his scope:

You will perhaps remember that during the hearing on “Problems of the Book of Mormon” reported to your Council January, 1922 I stated in my remarks that there were other problems which I thought should be considered in addition to those submitted in my report. Brother Richard R. Lyman asked if they would help solve the problems already presented, or if they would very greatly increase our difficulties. My answer was that they would very greatly increase our difficulties, on which he replied, “Then I do not know why we should consider them.” My answer was, however, that it was my intention to go on with the consideration to the last analysis.

In writing out this my report to you of those studies, I have written it from the viewpoint of an open mind, investigating the facts of the Book of Mormon origin and authorship.

[My purpose is] to make it of record for those who should be its students and know on what ground the Book of Mormon may be questioned, as well as that which supports its authenticity and its truth. . . .

Let me say once and for all, so as to avoid what might otherwise call for repeated explanation, that what is herein set forth does not represent any conclusions of mine. This report herewith submitted is what it purports to be, namely a “study of Book of Mormon origins,” for the information of those who ought to know everything about it pro et con, as well as that which has been produced against it and that which may be produced against it. I am taking the position that our faith is not only unshaken but unshakeable in the Book of Mormon, and therefore we can look without fear upon all that can be said against it.

It is not necessary for me to suggest that maintenance of the truth of the Book of Mormon is absolutely essential to the integrity of the whole Mormon movement, for it is inconceivable that the Book of Mormon should be untrue in its origin or character and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints be a true church.

In the first part, Roberts considers the possibility that Ethan Smith’s A View of the Hebrews, published in 1823 with a second edition in 1825, supplied the structural outline for the Book of Mormon, published in 1830. Ethan Smith’s A View of the Hebrews describes the evidence for the conclusion held by many writers at the time that the lost tribes of Israel were “the aborigines of our continent.” In fourteen chapters, Roberts compared similar elements in the two books, including the destruction of the civilized branch of a divided people, discovery of an ancient buried record, the “two sticks” passage of Ezekiel applied to the American Indian, the Urim and Thummim, the use of Egyptian writing, and the application of Isaiah 18 to convert the Indians.[16] Roberts felt that Joseph Smith probably had access to A View of the Hebrews.[17]

In the second part of “A Book of Mormon Study,” Roberts considers evidence that the Book of Mormon was the product of a relatively unsophisticated imagination. He mentioned long journeys taken and large cities built in very short periods of time, noted that the Jaredite and Nephite migrations have parallel story lines, and that the anti-Christ episodes are repeated in nearly identical patterns. A call to the Eastern States Mission presidency later in 1922 interrupted Roberts’s presentation of “A Book of Mormon Study” to the First Presidency.

In 1927, Roberts wrote Apostle Richard R. Lyman, including, “A Parallel,” an eighteen-page condensation of parallels between the Book of Mormon and A View of the Hebrews. Roberts wanted Lyman to present the summary to the Council of the Twelve, perhaps to see how his longer work might be received. Roberts explained,

I thought I would submit in sort of tabloid form a few pages of matter pointing out a possible theory of the origin of the Book of Mormon that is quite unique and never seems to have occurred to anyone to employ, largely on account of the obscurity of the material on which it might be based, but which in the hands of a skillful opponent could be made, in my judgment, very embarrassing.

I submit it in the form of a Parallel between some main outline facts pertaining to the Book of Mormon and matter that was published in Ethan Smith’s “View of the Hebrews” which preceded the Book of Mormon, the first edition by eight years, and the second edition by five years, 1823-5 respectively. It was published in Vermont and in the adjoining country in which the Smith family lived in the Prophet Joseph’s boyhood days, so that it could be urged that the family doubtless had this book in their possession, as the book in two editions flooded the New England States and New York. . . .

I submit it to you and if you are sufficiently interested you may submit it to others of your Council.[18]

It is not known if Roberts’s questions were discussed in further council meetings.

The Outcome of Roberts’s Studies

Roberts’s biographer, Truman Madsen, has suggested that “it is not clear how much of this typewritten report [“A Book of Mormon Study”] was actually submitted to the First Presidency and the Twelve.”[19] However, on 7 August 1933, the month before Roberts died, Wesley P. Lloyd recorded his three-and-a-half hour conversation with Roberts on problems of Book of Mormon authenticity. Lloyd had served a mission under Roberts and had come to know him well. As Lloyd recorded the event, Roberts had sent his 400-page thesis on the origin of the Book of Mormon “to Pres. Grant.”[20] Madsen further adds that Roberts did not intend this study for “further dissemination.”[21] However, Grant Ivins, BYU professor of comparative religion and son of Elder Anthony W. Ivins, wrote in a personal letter to a friend who wanted to know, among other things, if the Book of Mormon were “true” that Roberts had “wanted to publish this comparison, but the Church authorities would not sanction its publication.”[22] Ivins’s statement, which he reports as B. H. Roberts’s without saying whether his knowledge is first-hand, supports the idea that Roberts did present his second study to the Church authorities and that he intended to publish it.

Little more was heard of Roberts’s two studies for the next half century. However, in 1946, B. H. Roberts’s son, Benjamin, discussed Book of Mormon parallels to A View of the Hebrews and distributed a list similar to his father’s “Parallel.”[23] The previous year, Fawn Brodie referred to parallels between the Book of Mormon and A View of the Hebrews in a footnote to her biography of Joseph Smith, No Man Knows My History.[24] These discussions of parallels, however, do not mention Roberts’s 1921 and 1923 studies.[25]

In two 1959 Improvement Era articles, Hugh Nibley referred to Book of Mormon parallels with A View of the Hebrews but likewise did not mention the two Roberts studies.[26] Several LDS Church histories have been written without citing either A View of the Hebrews or Roberts’s studies. Screened by a committee of General Authorities, Roberts’s own A Comprehensive History of the Church, published in 1930, omitted any mention of his two previous studies. Elder Joseph Fielding Smith’s Essentials of Church History (1922), James B. Allen’s and Glen M. Leonard’s The Story of the Latter-Day Saints (1976) and Leonard J. Arrington’s and Davis Bitton’s The Mormon Experience (1979) also do not mention the Roberts studies. Truman Madsen’s biography also follows this cautious precedent. In a 1983 Ensign article on Roberts, he acknowledges “only two specific similarities,” aside from the claim of Hebraic backgrounds, between the Book of Mormon and A View of the Hebrews: lengthy Isaiah quotes and reference to the Urim and Thummim. Then, misdating the second edition of A View of the Hebrews at 1835 instead of 1825, he erroneously asserts that this edition was “published long after the Book of Mormon began circulation,” suggesting that when A View of the Hebrews was revised and enlarged, “it surely can also be claimed that Ethan Smith was aware of Joseph Smith’s [book].”[27]

Are Roberts’s Questions Still Relevant?

At this point, we need to determine what Roberts himself may have concluded about the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, and whether the questions he raised can now be answered. Was Roberts seriously and personally concerned about these questions or was he presenting a rhetorical case to Heber J. Grant and the Twelve in an attempt to arouse committed inquiry? From our perspective, are Roberts’s concerns out of date or have his questions generally been answered? Let us deal first with the second question.

Roberts poses two general classes of questions, archeological and literary. Whereas certain issues deal with literary inconsistencies in the Book of Mormon and its possible derivation from contemporary source material such as Ethan Smith’s A View of the Hebrews, archeological questions of Indian origins, languages, and lifestyles treat evidence which is constantly examined by specialists in the fields of archeology and anthropology.

For example, archeologists generally agree that North, Central, and South America were populated by waves of migrations across the 2,000-kilometer wide Bering Strait land bridge from Asia during a 15,000-year span in the late Wisconsin Ice Age, ending about 8,000 B.C. No anthropologist disputes the evidence of bones from animal kills. Early humans left a clearly marked trail down and across the Americas. The majority of early native American populations evidently arrived by this overland route.[28] It is this scientific consensus of his time, still a majority opinion, that Roberts presented in his study.

A current minority school works with the possibility of transoceanic contacts among early cultures from the Old World and the New.[29] At one point, anthropologists were debating whether pottery found in Ecuador and Columbia dating back to 3,000 B.C. may have originated in Japan.[30] The possibility of transoceanic contacts would certainly allow early voyages such as those described in the Book of Mormon while accommodating the Bering Straits evidence. This view is, of course, closely related with the currently advanced hypothesis that the Book of Mormon records activities that took place in a limited geographical region. As John L. Sorenson argues in a lengthy examination that has circulated in typescript,[31] the Book of Mormon text describes foot journeys between Nephi and Zarahemla that took place in some twenty days (approximately 500 miles); a population of about 2,500 assembled in Bountiful in 3 Nephi 10-18 for the visitation of the Savior, and military units at the end of the book numbering in the tens of thousands, rather than mil lions. Biblical references, a possible parallel, to “all the land,” Sorenson concludes, seem to be a matter of Hebrew hyperbole rather than exact geographical descriptions. (See Josh, 11:23; Isa. 13:5; Jer. 1:18; Matt. 27:45; Luke 23:44).

Still, even though this geographical hypothesis would resolve some of the difficulties presented by the numerous Indian languages present and by the clearly contradictory evidence of the Bering Straits, it is not without its problems. From the inception of the Church, Joseph Smith in “revealed” statements taught that the New World Indians—presumably all—were descended from Book of Mormon peoples. Joseph Smith’s quotation of Moroni’s 1823 instructions calls the book “an account of the former inhabitants of this continent, and the sources from whence they sprang.”[32]

On 4 Jan. 1833, Joseph Smith described “by commandment of God” his work on the Book of Mormon to N. E. Seaton, editor of a Rochester, New York, newspaper. Here he defines the Book of Mormon people as “the forefathers of our western tribes of Indians. . . . By it we learn that our western tribes of Indians are descendants from that Joseph which was sold into Egypt, and that the land of America is a promised land unto them.”[33] Apparently in explication of Book of Mormon descriptions that the Jaredites settled “all the face of the land” (Eth. 1:33-34, 42; 2:17, 7:11), an unsigned Times and Seasons editorial for the period when it was under Joseph Smith’s editor ship, says they “covered the whole continent from sea to sea with towns and cities.”[34] In his 1842 letter to John Wentworth, Joseph Smith further re affirmed that “the remnant [of Book of Mormon peoples] are the Indians that now inhabit this country.”[35] At conference in New York attended by the Quorum of the Twelve, 27 August 1843, Elder Orson Pratt identified the Book of Mormon as “a History of nearly one half of the globe & the people that inhabited it, that it gave a history of all those cities that have been of late discovered by Catherwood and Stephens [explorers of remains of early American civilizations].”[36] And at a 10 September 1843 conference in Boston at which seven of the Quorum of the Twelve were present, Elder Wilford Woodruff affirmed that the Book of Mormon record “contains an account of the ancient inhabitants of this continent who over spread this land with cities from sea to sea,” a restatement of the contemporary understanding that the people of Nephi “did cover the whole face of the land, both on the northward and on the southward, from the sea west to the sea east” (Hel. 11 :20).[37]

Roberts asked essentially: Why is there no archeological evidence of Book of Mormon animals and objects? Current anthropologists are in apparent agreement that pre-Columbian Americans possessed no domestic animals such as horses, cows, sheep, asses, oxen, or swine, although dogs and llamas, not mentioned in the Book of Mormon, were domesticated fairly early. Ancestors of the modern horse became extinct in North and South America about 12,000 B.C., at the end of the Pleistocene era; the horse was reintroduced by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. Although some Mormon scholars wish to defer judgment until more evidence is available, current evidence does not include the remains of horses.

Archeologists in B. H. Roberts’s time also generally agreed that wheat and barley, found only in the Old World, did not grow in North and South America until European colonists brought them here. A recently reported discovery of “what looks like domesticated barley” in the ruins of the Hohokam civilization in Arizona may require a modification of this view.[38] Early Indians had corn (maize), beans, tomatoes, squash, gourds, peppers, and root crops (potatoes, yams, sweet potatoes). Only after contact was made in the 1500s did Old World crops travel to the New World and vice versa. In addition, New World peoples apparently used copper, bronze, gold, and silver, but not iron or steel. Roberts suggests the mention of steel in the Book of Mormon is another parellel with Ethan Smith’s View of the Hebrews.[39] A hypothesis which Roberts did not consider but which is proposed by John W. Welch, director of FARMS (Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies), and others, is that the technology for hardening iron may have been lost. Nephi teaches his people to make steel (2 Ne. 5:15), but the last reference to steel is in Jarom 8, cited as 399 B.C.[40]

Small wheeled objects have been found near the Vera Cruz coast of Mexico, but there seems to be no evidence of wheeled vehicles or machinery in prehistoric America. Furthermore, the New World lacked draft animals to pull wheeled chariots even if they had existed. In Peru and Ecuador, the only places that had something similar to a draft animal, the llama, the “roads” were generally stepped footpaths, unusable for wheeled vehicles.[41]

Since we cannot disprove that which has not been found, the issue of whether a particular article or animal existed in pre-Columbian America remains unresolved. The proposed evidence for the horse and the wheel has not, however, been convincing.[42]

The admitted over-eagerness and lack of scholarly rigor of some in accepting highly selective Book of Mormon “proofs” has contributed to an embarrassing stereotype that more responsible scholarship must efface. Commenting upon Mormon attempts to provide archeological evidence for Joseph Smith’s translations, noted archeologist of Mesoamerica, Michael D. Coe of Yale University, stated:

Mormon archeologists over the years have almost unanimously accepted the Book of Mormon as an accurate, historical account of the New World peoples between about 2,000 B.C. and A.D. 421. They believe that Smith could translate hieroglyphs, whether “Reformed Egyptian” or ancient American, and that his translation of the Book of Abraham is authentic. Likewise, they accept the Kinderhook Plates as a bona fide archeological discovery, and the reading of them as correct. Let me now state uncategorically that as far as I know there is not one professionally trained archeologist, who is not a Mormon, who sees any scientific justification for believing the foregoing to be true, and I would like to state that there are quite a few Mormon archeologists who join this group. . . . The picture of this hemisphere between 2,000 B.C. and A.D. 421 presented in the book has little to do with the early Indian cultures as we know them, in spite of much wishful thinking. . . .

The bare facts of the matter are that nothing, absolutely nothing, has ever shown up in any New World excavation which would suggest to a dispassionate observer that the Book of Mormon, as claimed by Joseph Smith, is an historical document relating to the history of early migrants to our hemisphere.[43]

Perhaps in an effort to counter such blanket accusations, the New World Archaeological Foundation, organized in the 1950s by Thomas S. Ferguson and eventually taken over by the Church and based at Brigham Young University, responded with “considerable embarrassment over the various un scholarly postures” related to Book of Mormon-oriented archaeology. The Church Archaeological Committee instructed the NWAF employees that it “should concern itself only with the culture history interpretations normally within the scope of archaeology, and any attempt at correlation or interpretation involving the Book of Mormon should be eschewed.” Dee F. Green, an archaeologist employed by the foundation in 1963, remembers that “it was made quite plain to me . . . that my opinions with regard to the Book of Mormon archaeology were to be kept to myself, and my field report was to be kept entirely from any such references.”[44]Drawing on the findings of the New World Archaeological Foundation, among other sources, including their own research, FARMS and the Society for Early Historic Archaeology have remained alert to point out areas where the findings of archaeology may correspond with Book of Mormon claims. SEHA Newsletter editor Ross T. Christensen, in discussing the 1953 find of a bas-relief considered by some to be a portrayal of Lehi’s vision of the tree of life, expressed what is no doubt the hope of many colleagues: “If and when success in identifying a major Book of Mormon artifact in a Mesoamerican cultural context is confirmed, it is conceivable that Book of Mormon archaeological research could develop as a valid and vigorous branch of Mesoamerican studies . . . along lines similar to Near Eastern biblical archaeology, for expanding our knowledge of early Mesoamerica and of Book of Mormon peoples and places.”[45]

After reviewing the archeological issues that Roberts raised in 1921, one can see that the ensuing sixty years may have added more information but they have not fully resolved these questions. Whether Roberts was personally concerned or whether he was playing devil’s advocate, his written conclusions leave little doubt that he was indeed concerned.

How did he deal with these questions? Madsen presents an extensive summary of Roberts’s Book of Mormon-related activities and several quotations which suggest that Roberts accepted the authenticity of the Book of Mormon until his death. In recollections given to Madsen about fifty years later, one former missionary remembered how often Roberts said, “I have come to know the book is true”; another friend recalled Roberts concluding shortly before his death in 1933 that, “Ethan Smith played no part in the formation of the Book of Mormon.”[46]

However, several missionaries and close associates of Roberts recalled a possible change of mind on the Book of Mormon. Mark K. Allen, secretary to the Eastern States Mission presidency just after Roberts, remembered his saying, “We’re not through with the Book of Mormon. We’ve got problems. I could do Volume III of New Witnesses for God the other way and be just as convincing.”[47]Another missionary in the Eastern States under Roberts remarked that Roberts had recommended that missionaries not talk about the Book of Mormon; that Roberts had instructed him “to use the Bible, to approach converts in their own language and avoid the criticism that so often arose from using the Book of Mormon.”[48] These interviews both affirming and denying Roberts’s continuing faith in the Book of Mormon were recalled years later.

A month before Roberts’s death in September 1933, Lloyd recorded a “very interesting” three-and-a-half hour conversation with Roberts. He tells of Couch’s letter which Talmage gave Roberts

. . . to make a careful investigation and study and to get an answer for the letter. Roberts went to work and investigated it from every angle but could not answer it satisfactorily to himself. At his request Pres Grant called a meeting of the Twelve Apostles and Bro. Roberts presented the matter, told them frankly that he was stumped and asked their aid in the explanation. In answer, they merely one by one stood up and bore testimony to the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon.

Roberts wrote to President Grant of his “disappointment at the failure” and then “made a special Book of Mormon study.” Lloyd then records that Roberts

. . . swings to a psychological explanation of the Book of Mormon and shows that the plates were not objective but subjective with Joseph Smith, that his exceptional imagination qualified him psychologically for the experience which he had in presenting to the world the Book of Mormon and that the plates with the Urim and Thummim were not objective. He explained certain literary difficulties in the Book such as the miraculous incident of the entire nation of the Jaredites, the dramatic story of one man being left on each side, and one of them finally being slain, also the New England flat hill surroundings of a great civilization of another part of the country. We see none of the cliffs of the Mayas or the high mountain peaks or other geographical environment of early American civilization that the entire story laid in a New England flat hill surrounding. These are some of the things which has made Bro Roberts shift his base on the Book of Mormon.[49]

While these statements do not establish definitively that Roberts no longer believed the Book of Mormon to be the literal record of an ancient people, they clearly indicate a deepseated ambivalence on the subject which seemed to increase toward the end of his life. As recorded in his two critical studies, Roberts’s concerns with the Book of Mormon were substantive:

1. In “Book of Mormon Difficulties,” he summarizes the language difficulty: “That the time limits named in the Book of Mormon—which represents the people of America as speaking and writing one language down to as late a period as A.D. 400—is not sufficient to allow of these divergencies into the American language stocks and their dialects.” The limited geography hypothesis would largely resolve this difficulty, but that hypothesis is another of Roberts’s objections.

2. “If such other races or tribes existed then the Book of Mormon is silent about them. Neither the people of Mulek nor the people of Lehi or after they were combined, nor any of their descendants ever came in contact with any such people, so far as any Book of Mormon account of it is concerned.”

3. Regarding the absence of domestic animals, grains, metals, and wheeled vehicles among early Indians, Roberts, at the end of Section II, quotes the scholarly consensus of the time that some of the articles mentioned in the Book of Mormon do not seem to have existed in prehistoric America, then spells out the implications of the issue:

There can be no question but what the Book of Mormon commits us to the possession and use of domestic animals by both Jaredite and Nephite peoples; and to the age and civilization of iron and steel and of the wheel, and of a written language, by both these peoples. And they, with their descendants, constitute all the inhabitants of the New World, so far as the Book of Mormon informs us, except as to the Gentile races which by the spirit of prophecy it was foreseen would come in later times.

What shall our answer be then? Shall we boldly acknowledge the difficulties in the case, confess that the evidences and conclusions of the authorities are against us, but notwithstanding all that, we take our position on the Book of Mormon and place its revealed truth against the declarations of men, however learned, and await the vindication of the revealed truth? Is there any other course than this? And yet the difficulties to this position are very grave. Truly we may ask “Who will believe our report?” in that case. What will the effect be upon our youth of such a confession of inability to give a more reasonable answer to the questions submitted, and the awaiting of proof for final vindication? Will not the hoped-for proof deferred indeed make the heart sick? Is there any way to escape these difficulties?

4. Returning to the problematic LDS teaching of Indian origins, Roberts, at the conclusion of Section III, surveys theories about the origin of the native Americans and summarizes the combination of events the Book of Mormon implies:

But what is required is that evidence shall be produced that will give us an empty America 3,000 years B.C., into which a colony from the Euphrates Valley (supposedly) may come and there establish a race and an empire with an iron and steel culture; with a highly developed language of that period; then, after an existence of about sixteen or eighteen hundred years shall pass away, become extinct in fact, as a race and as a nation; this about 600 B.C., leaving the American continents again without human inhabitants.

Then into these second time empty American continents—empty of human population—we want the evidence of the coming of two small colonies about 600 B.C., which shall be the ancestors of all native American races as we know them; possessing as did the former race, domestic animals, the horse, ass and cow; with an iron and steel culture, and a highly developed written literature, the national Hebrew literature in fact.

Can we successfully overturn the evidences presented by archeologists for the great antiquity of man in America, and his continuous occupancy of it, and the fact of his stone age culture, not an iron and steel culture? Can we successfully maintain the Book of Mormon’s comparatively recent advent of man in America and the existence of his iron and steel and domestic animal, and written language stage of culture against the deductions of our late American writers upon these themes?

In Roberts’s own words, these concerns were answered in January 1922 with “faithful testimonies,” an answer which disappointed Roberts and motivated his second paper, “A Book of Mormon Study.”

Roberts presents his most somber assessments of problematic authenticity of the Book of Mormon in his 1923 study.- His own comments follow, by part and chapter. In Part I, Chapter I, Roberts observes that Joseph Smith could have based the Book of Mormon on legends and beliefs that were “common knowledge” in nineteenth century New England.

It will appear in what is to follow that such ”common knowledge” did exist in New England; that Joseph Smith was in contact with it; that one book, at least, with which he was most likely acquainted, could well have furnished structural outlines for the Book of Mormon; and that Joseph Smith was possessed of such creative imaginative powers as would make it quite within the lines of possibility that the Book of Mormon could have been produced in that way.

In Part I, Chapter IX, Roberts recognizes the “cumulative force” of many points of similarity which “menace” Joseph Smith’s story:

Did Ethan Smith’s A View of the Hebrews furnish structural material for Joseph Smith’s book of Mormon? It has been pointed out in these pages that there are many things in the former book that might well have suggested many major things in the other. Not a few things merely, one or two, or a half dozen, but many; and it is this fact of many things of similarity and the cumulative force of them, that makes them so serious a menace to Joseph Smith’s story of the Book of Mormon’s origin.

The expression of this thoughtful Church authority conveys to his readers today the attitudes which he held about these “difficulties.” In his 15 March 1923 letter to President Grant and the Council of the Twelve, already cited, he asserts that the manuscript does not “represent any conclusions of mine” and that “our faith is not only unshaken, but unshakeable in the Book of Mormon.”[50] Still, enough evidence exists to suggest that this statement may have derived from a sensitivity to his audience and a desire to assure them that the document was not presented in any spirit of attack. His “disappointment” at the apparent disregard of his document was no doubt partly occasioned by the lack of serious consideration given to a project upon which he had devoted so much care and scholarly attention. However, it is not impossible that part of that disappointment was also personal — that even the questions of a General Authority, honestly and carefully arrived at, did not merit sober and serious consideration.

Certainly it is not possible to determine beyond all question what Roberts himself believed about the Book of Mormon as his life drew to a close. Evidence about both positive affirmation and private doubts coexists. The scholarly evidence of the times did not present him with a great range of options and, despite the advances of the ensuing sixty years, impartial archaeological research has not made the “difficulties” disappear although it has supplied additional evidence and produced additional hypotheses—even though these hypotheses are not without their problems.

Roberts began his quest for truth armed with “unshakable” faith, but the issues he raised concern the foundation of the Church. Did Joseph Smith translate the Book of Mormon from gold plates that held the authentic record of an ancient people? After years of research on the Book of Mormon, this tenacious General Authority found serious “menaces” to its authenticity. Many of the questions that deeply concerned Roberts in these two incisive studies still remain without satisfactory answers.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Although Truman G. Madsen does not discuss these works in his biography, Defender of the Faith, The B. H. Roberts Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), he devotes considerable attention to them in “B. H. Roberts and the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 19 (Summer 1979) : 427-45; and deals with them in the light of B. H. Roberts’s commitment to the Book of Mormon in “B. H. Roberts after Fifty Years: Still Witnessing for the Book of Mormon,” Ensign 13 (Dec. 1983): 11—19. See also Thomas G. Alexander’s review of Defender of the Faith in BYU Studies 21 (Spring 1981):248-50, which notes the omission of discussion on the Book of Mormon manuscripts.

[2] A View of the Hebrews; or the Tribes of Israel in America (Poultney, Vermont: Smith & Shute, 1823, 2nd ed. rev. and enl, 1825). Ethan Smith was a pastor of a Congregational Church in Poultney. In A View of the Hebrews, he collected the comments of numerous authors and travelers who were convinced that the American Indians were descended from the lost tribes of Israel. In 1977, Arno Press, New York, a subsidiary of the New York Times, reprinted the 1823 edition as part of an America-Holy Land Studies sponsored by the American Jewish Historical Society and the Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In 1964, Modern Microfilm Company (later Utah Lighthouse Ministry), Salt Lake City, photomechanically reproduced Roberts’s own copy of the 1825 edition.

[3] During the 1979 and 1980 Sunstone Theological Symposiums, Madison U. Sowell and I presented papers discussing Roberts’s studies on the Book of Mormon. These papers were later published together, Sowell “Defending the Keystone: The Comparative Method Re examined” and Smith “Defending the Keystone: Book of Mormon Difficulties,” Sunstone 6 (May-June 1981): 44-54.

[4] On 27 Dec. 1979, the University of Utah Special Collections Library received Roberts’s 1921 and 1923 papers and correspondence from Adele W. Parkinson, widow of Wood R. Worsley, a grandson of Roberts’s first wife, Louisa. On 19 Jan. 1981, Virginia Roberts, widow of Brigham E. Roberts, another grandson of Louisa, gave the library personal copies of the papers. Under an exchange agreement, Brigham Young University Library received copies of both sets. The published volume, B. H. Roberts: Studies of the Book of Mormon will be introduced and edited by Brigham D. Madsen and prefaced by Everett L. Cooley. It includes a biographical essay on Roberts by Sterling M. McMurrin, a member of the Roberts family.

[5] “Children of Lehi — Where Are They? LDS Church News, 29 Feb. 1984, p. 3.

[6] Apostle George F. Richards recorded in his diary, Wednesday, 4 Jan. 1922: “I made the talk at the temple meeting 9 A.M. and from 10 A.M. to 6 P.M., except while attending to sealing ordinances, was in a meeting of the presidency, the Twelve, and the Council of Seventy hearing Pres. B. H. Roberts present a paper of 141 typewritten pages he had prepared while considering five questions upon the Book of Mormon submitted by a Mr. Couch of Washington, D.C.” Historical Department Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah; hereafter LDS Church Archives. See also, James E. Talmage, Journal, 4, 5, and 26 Jan. 1922, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[7] Scimitar or scimiter are English terms derived from the Persian saber or shamshir. Leonid Tarassukand, Claude Blair, eds., The Complete Encyclopedia of Arms and Weapons (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982), pp. 416, 419-21.

[8] Wesley P. Lloyd, Journal, 7 Aug. 1933, in possession of Lloyd family. Lloyd, a close friend of Roberts, served as Dean of Men, Dean of Students, and Dean of the Graduate School at BYU. See also Roberts to George W. Middleton, 11 Nov. 1921 and Roberts to R. V. Chamberlin, 3 Dec. 1921; letters in Roberts Collection, University of Utah and BYU libraries.

[9] Talmage, Journal, 4, 5, and 26 Jan. 1922.

[10] Lloyd, Journal, 7 Aug. 1933.

[11] B. H. Roberts to Heber J. Grant, 9 Jan. 1922, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. The diary entries of Heber J. Grant for 4 Jan. 1922 and several following days, currently inaccessible to researchers (LDS Church Archives), may describe reactions to the Roberts presentation.

[12] See Talmage, Journal, 2 Feb. 1922, for the date of the meeting to assist Roberts in preparing the Couch letter.

[13] Here Roberts is referring to a position that was just beginning to emerge at the time: the idea that the Book of Mormon people were one of many groups of ancestors of the present-day Indians.

[14] B. H. Roberts to Heber J. Grant, 15 March 1923.

[15] Talmage, Journal, 29 March, 28 April, and 25 May 1922. It is possible that Roberts finished the paper in March 1922. He left on a mission later that year; a 1927 letter to Richard Lyman implies 1922, and the 1923 date was added by hand to the typed copy.

[16] These similar ideas to Book of Mormon themes are found in A View of the Hebrews (1825 ed.): Indians from Hebrew tribes (p. 85 and passim); destruction of civilized branch (p. 172); buried record (pp. 115, 217-23) ; “two sticks” (pp. 52-54); Urim and Thummim (pp. 150, 195); Egyptian writing (pp. 182-85); Isaiah and converting Indians (pp. 228, 249-50). Although several Book of Mormon chapters quote Isaiah chapters, Isaiah 18 is not among them.

[17] A View of the Hebrews enjoyed widespread popularity; the first edition sold out and the second edition (pp. vi-vii) contained a letter of recommendation dated 4 Feb. 1825 from Rev. Jabez Hyde of Eden, Erie County, New York, further west than Joseph Smith’s residence in Palmyra and several hundred miles from the publisher in Poultney, Vermont.

[18] B. H. Roberts to Richard Lyman, 24 Oct. 1927. “A Parallel,” still attached to Roberts’s letter, is at the University of Utah Library.

[19] See Madsen, “B. H. Roberts and the Book of Mormon,” p. 440; also his “B. H. Roberts After Fifty Years,” p. 13, where he asserts that Roberts “had sent the entire 435 pages to President Heber J. Grant .. . on 15 March 1923.” Since Roberts had quite clearly delivered the first 141 pages in 1922, Madsen seems to be first questioning whether Roberts had delivered the second paper, then assuming such delivery, and also assuming that the cover letter was to accompany his 1923 study. This conclusion is open to question. Roberts would refer to his manuscript as 400 pages long, both in a letter to Elizabeth Skofield (Madsen, “After Fifty Years,” p. 13) and in his 1933 conversion with Wesley P. Lloyd (n. 8), apparently a rounded-off number. The manuscript of “A Book of Mormon Study” is actually 291 pages rather than Madsen’s figure of 285, who apparently derives his total of 435 pages by adding the 285 pages in the second study, the 141-page first study, and the two cover letters totaling nine pages. Roberts also included several pages of abstracts which are not paginated, from contemporary and historical works pertaining to the subject.

[20] Lloyd, Journal, 7 Aug. 1933.

[21] For example, see Madsen, “B. H. Roberts and the Book of Mormon,” p. 440, and ” B. H. Roberts after Fifty Years,” p. 13.

[22] Grant Ivins to Hebe r Holt, 26 Dec. 1967; copy in Special Collections Library, University of Utah . Madsen cites B. H. Roberts to Elizabeth Skolfield, 14 March 1932, in which he says his “Book of Mormon Study” was “not for publication.” “B. H . Roberts after Fifty Years,” p. 13.

[23] Meeting of the Timpanogos Club, 10 Oct. 1946, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Subsequently, Mervin B. Hogan published the mimeographed list of parallels in The Rocky Mountain Mason (Billings, Montana), Jan. 1956, pp. 17—31. In 1963, Hal Hougey reproduced Roberts’s parallels in a pamphlet entitled A Parallel: The Basis of the Book of Mormon (Concord, Calif.: Pacific Publishing Co., 1963).

[24] Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History; The Life of Joseph Smith (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945), p. 47n.

[25] The Historical Department Archives of the Church does not include either manuscript in its register of B. H. Roberts’s unpublished works. Family copies were also apparently unavailable until 1979 although there is an unconfirmed report that Benjamin Roberts showed his copy to some researchers.

Perhaps Benjamin Roberts was the source of the “fragments” A. C. Lambert, a member of BYU’s faculty, recalls seeing in 1925: “A few of us at BYU got a few fragments of the manuscript back in 1925, but were ordered to destroy them and to ‘keep your mouths shut,’ and we did keep our mouths shut. I never got the fragments for my own meager files, which were kept private even then. B. H. Roberts came about as near calling Joseph Smith, Jr. a fraud and deceit as the polite language of a religious man would permit. The grandson who currently owns the manuscript died a few weeks ago as you may already have heard. I have not heard what will happen to the manuscript.” A. C. Lambert to Wesley P. Walters, undated but postmarked Dec. 14, 1978, Special Collections, University of Utah library.

[26] Hugh Nibley, “The Comparative Method,” Improvement Era 62 (Oct. 1959): 10; and ibid. 62 (Nov. 1959): 11.

[27] “B. H. Roberts after Fifty Years,” p. 17.

[28] See Jessie D. Jennings, ed., Ancient Native Americans (San Francisco: Freeman, 1978). Jennings, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of Utah and member of the National Academy of Sciences, here synthesizes the contributions of specialists in each major culture area in North, Central, and South America.

[29] Stephen C. Jett, “Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts,” in Jennings, ed., Ancient Native Americans, pp. 593-650. Jett concludes his survey of the evidence with a summary of professional opinion on transoceanic contacts: “Most scholars admit to the likelihood of sporadic accidental transoceanic contacts but tend to discount the possibility of significant extracontinental influences” (p. 639). Jett comments that the burden of supporting a trans oceanic view was increased by unfounded efforts to prove a preconceived theory or religious viewpoint: “So many unfounded surmises, religious theories, and even fraudulent ‘finds’ had occurred by the early twentieth century that serious study of possible early Mediterranean American relations became, through ‘guilt by association,’ even more of an anathema to scholarship than did consideration of possible transpacific ties” (pp. 623-24). See also Robert Wauchope, in Lost Tribes and Sunken Continents (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

[30] Betty J. Meggers, Clifford Evans, and Emilio Estrada, “Early Formative Period of Coastal Ecuador; the Valdivia and Machalilla Phases” in Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology 1 (1965). See discussion in Jennings, Ancient Native American, p. 602. T. Patrick Culbert, professor of anthropology, University of Arizona, observed that at one time about half the archeologists thought that the Valdivian pottery might be of Japanese origin; currently only about 10 or 15 percent consider it so (notes of a conversation with author, 12 Aug. 1980).

[31] “An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon,” typescript, 1978, esp. Ch. 1. This study examines textual evidence for a Mesoamerican setting and summarizes information currently available on ancient Mesoamerican cultures that seems to illuminate the Book of Mormon. This work is undergoing final revision in preparation for publication. In 1954, Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith rejected a limited-geography thesis: “Within recent years there has arisen among certain students of the Book of Mormon a theory to the effect that within the period covered by the Book of Mormon, the Nephites and Lamanites were confined almost within the borders of the territory comprising Central America and the southern portion of Mexico; the Isthmus of Theuantepec probably being the ‘narrow neck’ of land spoken of in the Book of Mormon rather than the Isthmus of Panama. . . . This modernistic theory of necessity, in order to be consistent, must place the waters of Ripliancum and the Hill Cumorah someplace within the restricted territory of Central America, notwithstanding the teachings of the Church to the contrary for upwards of 100 years. Because of this theory some members of the Church have been confused and greatly disturbed in their faith in the Book of Mormon. ” Deseret News, Church Section, 27 Feb. 1954, pp. 2-3. One of the relatively few official statements on Book of Mormon geography is George Q. Cannon, “The Book of Mormon Geography,” Juvenile Instructor 25 (1 Jan. 1890): 18, discouraging the creation and circulation of “suggestive maps” because of the lack of consensus of their authors, and stating that the First Presidency and Twelve have consistently declined invitations to prepare such a map.

[32] Joseph Smith, Jr., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, B. H. Roberts, ed., 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 1:2.

[33] Ibid., 1:315, 326.

[34] Times and Seasons 3 (15 Sept. 1842): 922.

[35] Quoted in Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930), 1:167.

[36] Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff Journals, Typescript (Midvale, Utah: Signature Books, 1983), 2:282.

[37] Ibid., 2:300. On 28 July, 1847, after the Saints had arrived in Utah, Brigham Young, speaking before the Quorum of the Twelve, stated that “our people would be connected with every tribe of Indians throughout America & that our people would yet take their squaws wash & dress them up teach them our language & learn them the gospel of there forefathers & raise up children by them & teach the children & not many generations Hence they will become A white & delightsome people.” (Ibid., 3:241.) In 1875, Orson Pratt quoted his memory of Joseph Smith saying that “The Lord God made a promise to the forefathers of the Indians, about six hundred years before Christ, that all this continent should be given to them and to their children after them for an everlasting inheritance.” Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1875), 17:299-301. Pratt further asserted that the Indians “have different languages, but the roots of each language indicate that they have all sprung from the same origin” (19 Feb. 1871, Journal of Discourses, 14:10). In 1954, Joseph Fielding Smith, then an apostle, reaffirmed that Nephites “spread over the face of the entire continent” and that “their descendants, the American Indians, were wandering in all their wild savagery when the Pilgrim Fathers made permanent settlement in this land.” Doctrines of Salvation, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954), 1:151. The missionary program to the Indians identifies them as the fallen descendants of the early Book of Mormon peoples. See Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 17:299-301; 14:10. Other sources include Parley P. Pratt, A Voice of Warning (Liverpool: Brigham Young, 1866), pp. 94- 109; George Q. Cannon’s 6 April 1884 General Conference address in Journal of Discourses, 25: 123-24; and Orson Pratt’s 2 Dec. 1877 address, in Journal of Discourses, 19:170-74.

In 1966 Bruce R. McConkie, later an apostle, acknowledged: “It is quite apparent that groups of Orientals found their way over the Bering Strait gradually moved southward to mix with the Indian peoples.” However, Indians are still regarded as “chiefly” Lamanites, whom McConkie considers to have come prior to the Bering Strait migrations, which archaeologists date thousands of years earlier. (Mormon Doctrine, 2nd ed. [Salt Lake City: Book craft, 1966], pp. 32—33). Church historians Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton reflect this modified view, probably held widely, that the Indian population “apparently mixed with other groups from Europe and Asia [to become] the ancestors of the Indians of North, Central, and South America” but without discussion of proportions or order of arrival (The Mormon Experience, p. 14).

[38] Daniel B. Adams, “Last Ditch Archeology,” 4 Science ’83 (Dec. 1983): 32, 30-31. The Hohokam, who vanished about 600 years ago, may have migrated from Mexico—the point is “hotly debated”—and built houses of a “kind of concrete made from a local mineral called caliche.”

[39] See John L. Sorenson, “A Reconsideration of Early Metal in Mesoamerica,” Museum of Anthropology Miscellaneous Series, no. 45, 1982, University of Northern Colorado Museum of Anthropology, Greeley, Colorado; also available in the reprint series of the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Box 7113, University Station, Provo, U T 84602. He summarizes metallic finds reported since the mid-1950s including some possible iron objects. The footnoted and annotated script for a FARMS filmstrip, “Lands of the Book of Mormon,” pp. 19-20, states: “Between 1475 and 1125 B.C. on a recalibrated C-14 scale, magnetite and ilmenite (native iron) mirrors were being manufactured in the Oaxaca Valley. (Flannery and Schoenwetter, Archaeology, 23:2:149). A geological map is available in K. Flannery, editor, The Early Mesoamerican Village, New York:

Academic Press, 1976, p. 318, figure 10.10 showing the procurement routes along the known sources of iron ore in Oaxaca Valley. Jane W. Peres-Ferreira’s article, ‘Shell and Iron-Ore Mirror Exchange in Formative Mesoamerica,’ in the Flannery volume examines this early metal working in some detail.” This time frame would correspond to Jaredite times when steel is mentioned in Ether 7:9.

[40] John W. Welch, “Memorandum,” 10 April 1984. Needless to say, the evidence for metallic use in ancient America, though sufficiently tantalizing as to merit continued examination, has so far lacked the conclusiveness necessary to create a clear revision of the general scholarly consensus.

[41] Jennings, Ancient Native Americans, passim. Conversations with T. Patrick Culbert, professor of anthropology, University of Arizona, specialist in Mayan civilization and its collapse (12 Aug. 1980) ; William Hawk, professor of anthropology, University of Wisconsin (8 Aug. 1980) ; Richard S. MacNeish, Robert S. Peabody Foundation for Archeology, Andover (11 Aug. 1980); Michael D. Coe, anthropologist (12 Aug. 1980); William Ayres, Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon (8 Aug. 1980) ; Betty J. Meggers, Research Associate at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (8 Aug. 1980).

[42] See Paul R. Cheesman, “The Wheel in Ancient America,” BYU Studies 19 (Winter, 1969). His The World of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978) was criticized for “being inconsistent about his selection of evidence,” using hearsay evidence, and making an inadequate case for the presence of horses among Indians. The reviewer noted that “hundreds of ancient skeletons of animals have been found along these roads but none of horses.” The reviewer also noted a problem in using any science to prove a preconceived view: “I hope that the search for [the history of pre-Columbian America] will be continued by rational, somewhat skeptical men, who are searching for the truth. This important study must not be left to those who already possess the truth and must therefore confirm it to the point of distorting it.” J. Henry Ibarquen, “Mormon Scholasticism,” DIALOGUE : A JOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT 11 (Autumn 1978): 92-94. John L. Sorenson echoed a similar criticism. Commenting on unprofessional writing that passes under the heading of archeology, Sorenson noted: “Two of the most prolific are Professor Hugh Nibley and Milton R. Hunter; however, they are not qualified to handle the archeological materials their work often involves. . . . As long as Mormons generally are willing to be fooled by (and pay for) the uninformed, uncritical drivel about archeology and the scriptures which predominates, the few LDS experts are reluctant even to be identified with the topic” (“Some Voices From the Dust,” a review of Papers to the Fifteenth Annual Symposium on the Archeology of the Scriptures, DIALOGUE 1 (Spring 1966) : 144-49.

[43] Michael D. Coe, “Mormon Archaeology: An Outsider View,” DIALOGUE 8 (Summer 1973) : 41, 42, 46. Since that time, the research of Stanley B. Kimball, “Kinderhook Plates Brought to Joseph Smith Appear to Be a Nineteenth-Century Hoax,” Ensign 11 (Aug. 1981) : 66-74, seems to have laid to rest the Kinderhook Plates as modern forgeries, even though they have been widely accepted as recently as 1962 in official Church publications as an uncompleted translation by Joseph Smith, in the company of the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham.

[44] Dee F. Green, “Book of Mormon Archaeology: The Myths and the Alternatives,” DIALOGUE 4 (Summer 1969): 76.

[45] Society for Early Historic Archaeology Newsletter, no. 156 (March 1984).

[46] Madsen, “B. H. Roberts after Fifty Years,” pp. 11-19, Interview with Milo Marsden, 10 July 1983 and Jack Christensen, 25 April 1979.

[47] Conversation with author, 27 Aug. 1981 and 3 March 1984. Allen was secretary to Eastern States Mission President Rolapp until 1928. Madsen, citing a letter to him from Allen, 20 July 1983, quotes him as saying, “His [Roberts’s] faith in the divinity of the book was strong, but he agonized over the intellectual problems in justifying it” and was “uneasy with attempts to build a case out of trivial coincidence and gratuitous parallels.” “B. H. Roberts after Fifty Years,” p. 16.

[48] Conversation, 1 Aug. 1982 and 3 March 1984, with Harold Ellison, former bishop, stake president, and missionary in the Eastern States Mission under B. H. Roberts 1925-26. For a slightly different version of these instructions, see Madsen, “B. H. Roberts after Fifty Years, ” p . 16.

[49] Lloyd, Journal, 7 Aug. 1933. To my knowledge, Madsen does not discuss this source in print.

[50] B. H. Roberts to Heber J. Grant et al., 15 March 1923, University of Utah and Brigham Young University libraries.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue