Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 4

Jesus’ Dispute in the Temple and the Origin of the Eucharist

Critical discussion of Jesus throughout the modern period has been stumped by a single, crucial question. Anyone who has read the Gospels knows that Jesus was a skilled teacher, a rabbi in the parlance of early Judaism. He composed a portrait of God as divine ruler (“the kingdom of God,” in his words) and wove it together with an appeal to people to behave as God’s children (by loving both their divine father and their neighbor). At the same time it is plain that Jesus appeared to be a threat both to Jewish and to Roman authorities in Jerusalem. He would not have been crucified otherwise. The question which has nagged critical discussion concerns the relationship between Jesus the rabbi and Jesus the criminal: how does a teacher of God’s ways and God’s love find himself on a cross?

Scholarly pictures of Jesus which have been developed during the past two hundred years typically portray him as either an appealing, gifted teacher or as a vehement, political revolutionary. Both kinds of portrait are wanting. If Jesus’ teaching was purely abstract, a matter of defining God’s nature and the appropriate human response to God, it is hard to see why he would have risked his life in Jerusalem and why the local aristocracy there turned against him. On the other hand, if Jesus’ purpose was to encourage some sort of terrorist rebellion against Rome, why should he have devoted so much of his ministry to telling memorable parables in Galilee? It is easy enough to imagine Jesus the rabbi or Jesus the revolutionary. But how can we do justice to both aspects, and discover Jesus, the revolutionary rabbi of the first century?

Although appeals to the portrait of Jesus as a terrorist are still found today, current fashion is much more inclined to view him as a philosophical figure, even as a Jewish clone of the peripatetic teachers of the Hellenistic world. But the more abstract Jesus’ teaching is held to be—and the more we conceive of him simply as uttering timeless maxims and communing with God—the more difficulty there is in understanding the resistance to him. For that reason, a degree of anti-Semitism is the logical result of trying to imagine Jesus as a purely non-violent and speculative teacher. A surprising number of scholars (no doubt inadvertently) have aided and abetted the caricature of a philosophical Jesus persecuted by irrationally violent Jews.

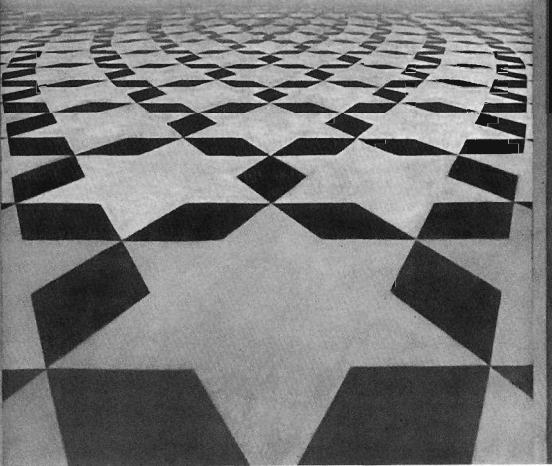

[Editor’s Note: For a depiction of the temple, see PDF below, p. 18]

The Gospels all relate an incident which, critically analyzed, resolves the problem of what we might call the two historical natures of Jesus. The passage is traditionally called “The Cleansing of the Temple” (see Matt. 21:12-16; Mark 11:15-18; John 2:14-22; and Luke 19:45-48). Jesus boldly enters the holy place where sacrifice was conducted and throws out the people who were converting the currency of Rome into money which was acceptable to the priestly authorities. He even expels vendors and their animals from the Temple, bringing the routine of sacrifice to a halt.

Such an action would indeed have aroused opposition from both the Roman authorities and the priests. The priests would be threatened be cause an important source of revenue was jeopardized, as well as the arrangements they themselves had condoned. The Romans would be concerned because they wished for political reasons to protect the operation of the Temple. They saw sacrifice there as a symbol of their tolerant acceptance of Jews as loyal subjects, and they even arranged to pay for some of the offerings.[1] The same Temple which was for the priestly class a divine privilege was for the Romans the seal of imperial hegemony.

The conventional picture of Jesus as preventing commercial activity in God’s house is appealing but over-simplified. It enables us to conceive of Jesus as opposing worship in the Temple, and that is the intention of the Gospels. They are all written with hindsight, in the period after the Temple was destroyed (in 70 Common Era [C.E.]), when Christianity was emerging as a largely non-Jewish movement. From the early fathers of Christianity to the most modern commentaries, the alluring simplicity of the righteous, philosophical Jesus casting out the “money-changers” has proven itself attractive again and again.

As is often the case, the conventional picture of Jesus may only be sustained by ignoring the social realities of early Judaism. Jesus in fact worshipped in the Temple and encouraged others to do so (see, for example, his instructions to the leper in Matt. 8:4; Mark 1:44; Luke 5:14). In addition, the picture of Jesus simply throwing the money-changers out of the Temple seems implausible. There were indeed “money-changers” as sociated with the Temple, whose activities are set down in the Mishnah. Every year the changing of money—in order to collect the tax of a half shekel for every adult male—went on publicly throughout Israel. The process commenced a full month before Passover, with a proclamation concerning the tax,[2] and exchanges were set up outside Jerusalem ten days before they were set up in the Temple. According to Josephus, the first century Jewish historian (and priest),[3] the tax was not even limited to those residing in the land of Israel, but was collected from Jews far and wide. An awareness of those simple facts brings us to an equally simple conclusion: the Gospels’ picture of Jesus is distorted. It is clear that he could not have stopped the collection of the half shekel by overturning some tables in the Temple.

A generation after Jesus’ death, by the time the Gospels were written, the Temple in Jerusalem had been destroyed and the most influential centers of Christianity were cites of the Mediterranean world such as Alexandria, Antioch, Corinth, Damascus, Ephesus, and Rome. There were still large numbers of Jews who were also followers of Jesus, but non-Jews came to predominate in the early church. They had control over how the Gospels were written after 70 C.E. and how the texts were interpreted. The Gospels were composed by one group of teachers after another during the period between Jesus’ death and 100 C.E. There is a reasonable degree of consensus that Mark was the first of the Gospels to be written, around 71 C.E. in the environs of Rome. As convention has it, Matthew was subsequently composed, near 80 C.E., perhaps in Damascus (or else where in Syria), while Luke came later, say in 90 C.E., perhaps in Antioch. Some of the earliest teachers who shaped the Gospels shared the cultural milieu of Jesus, but others had never seen him; they lived far from his land at a later period and were not practicing Jews. John’s Gospel was composed in Ephesus around 100 C.E. and is a reflection upon the significance of Jesus for Christians who benefitted from the sort of teaching the Synoptic Gospels represented.

The growth of Christianity involved a rapid transition from culture to culture and, within each culture, from sub-culture to sub-culture. A basic prerequisite for understanding any text of the Gospels, therefore, is to define the cultural context of a given statement. The cultural context of the picture of Jesus throwing money-changers out of the Temple is that of the predominantly non-Jewish audience of the Gospels, who regarded Judaism as a thing of the past and its worship as corrupt. The attempt to imagine Jesus behaving in that fashion only distorts our understanding of his purposes and encourages the anti-Semitism of Christians. Insensitivity to the cultural milieus of the Gospels goes hand in hand with a prejudicial treatment of cultures other than our own.

Jesus probably did object to the tax of a half shekel, as Matthew 17:24- 27 indicates. For him, being a child of God (a “son,” as he put it) implied that one was free of any imposed payment for the worship of the Temple. But a single onslaught of the sort described in the Gospels would not have amounted to an effective protest against the payment. To stop the collection would have required an assault involving the central treasuries of the Temple, as well as local treasuries in Israel and beyond. There is no indication that Jesus and his followers did anything of the kind, and an action approaching such dimensions would have invited immediate and forceful repression by both Jewish and Roman authorities. There is no evidence that they reacted in that manner to Jesus and his followers.

But Jesus’ action in the Temple as attested in the Gospels is not sim ply a matter of preventing the collection of the half shekel. In fact, Luke 19:45-46 says nothing whatever about “money-changers,” and because Luke’s Gospel is in some ways the most sensitive of all the Gospels to historical concerns, the omission seems significant. Luke joins the other Gospels in portraying Jesus’ act in the Temple as an occupation designed to prevent the sacrifice of animals which were acquired on the site. The trading involved commerce within the Temple, and the Jesus of the canonical Gospels, like the Jesus of the Gospel according to Thomas, held that “Traders and merchants shall not enter the places of my father” (Thomas, saying no. 64).

Jesus’ action in the Temple, understood as a means of protecting the sanctity of the Temple, is comparable to the actions of other Jewish teachers of his period. Josephus reports that the Pharisees made known their displeasure at a high priest (and a king at that, Alexander Jannaeus) by inciting a crowd to pelt him with lemons (on hand for a festal procession) at the time he should have been offering sacrifice.[4] Josephus also recounts the execution of the rabbis who were implicated in a plot to dismantle the eagle Herod had erected over a gate of the Temple.[5] By comparison, Jesus’ action seems almost tame; after all, what he did was to expel some vendors, an act less directly threatening to priestly and secular authorities than what some earlier Pharisees had done.

Once we understand that Jesus’ maneuver in the Temple was in essence a claim upon territory in order to eject those performing an activity he disapproved of, it seems more straightforward to characterize it as an “occupation”; the traditional “cleansing” is obviously an apologetic designation. The purpose of Jesus’ activity makes good sense within the con text of what we know of the activities of other early rabbinic teachers. Hillel, an older contemporary of Jesus, taught (according to the Babylonian Talmud, Shabbath 31) a form of what is known in Christian circles as the Golden Rule taught by Jesus: we should do to others as we would have them do to us. Hillel is also reported to have taught that offerings brought to the Temple should have hands laid on them by their owners and then be given over to priests for slaughter. Recent studies of the anthropology of sacrifice show why such stipulations were important. Hillel was insisting that, when the people of Israel came to worship, they should offer of their own property. Putting one’s hands on the animal about to be sacrificed was a statement of ownership.

The followers of a rabbi named Shammai are typically depicted in rabbinic literature as resisting the teachings of Hillel. Here, too, they take the part of the opposition. They insist that animals for sacrifice might be given directly to priests for slaughter; Hillel’s requirement of laying hands on the sacrifice is held to be dispensable. But one of Shammai’s followers was so struck by the rectitude of Hillel’s position, he had some 3,000 animals brought into the Temple and gave them to those who were willing to lay hands on them in advance of sacrifice.[6]

In one sense, the tradition concerning Hillel envisages the opposite movement from what is represented in the tradition concerning Jesus: animals are driven into the Temple rather than their traders being expelled. Yet the purpose of the action by Hillel’s partisan enforces a certain understanding of correct offering—and one which accords with a standard feature of sacrifice in the anthropological literature. Hillel’s teaching, in effect, insists upon the participation of the offerer by virtue of his owner ship of what is offered, while most of Shammai’s followers are portrayed as sanctioning sacrifice more as a self-contained, priestly action.

Jesus’ occupation of the Temple is best seen—along lines similar to those involved in the provision of animals to support Hillel’s position— as an attempt to insist that the offerer’s actual ownership of what is offered is a vital aspect of sacrifice. Jesus, as we will see, did not oppose sacrifice as such by what he did. His concern was with how Israelites ac quired and then offered their own sacrifices.

Jesus’ occupation of the Temple thus occurred within the context of a particular dispute in which the Pharisees took part, a controversy regard ing the location of where animals for sacrifice were to be acquired. In that the dispute was intimately involved with the issue of how animals were to be procured, it manifests a focus upon purity which is akin to that at tributed to Hillel.

The nature and intensity of the dispute are only comprehensible when the significance of the Temple, as well as its sacrificial functioning, are kept in mind. Within the holy of holies, enclosed in a house and be yond a veil, the God of Israel was enthroned in a virtually empty room. Only the high priest could enter that space, and then only once a year, on the day of atonement; at the autumnal equinox the rays of the sun could enter the earthly chamber whence the sun’s ruler exercised dominion, because the whole of the edifice faced east. Outside the inner veil (still within the house) the table of the bread of the presence, the menorah, and the altar for incense were arranged. The house of God was just that: the place where he dwelled, and where he might meet his people.

Immediately outside the house, and down some steps, the altar itself, of unhewn stones and accessible by ramps and steps, was arranged. Priests had regularly to tend to the sacrifices, and male Israelites were also admitted into the court structure which surrounded the altar. Various specialized structures accommodated the needs of the priests, and chambers were built into the interior of the court (and, indeed, within the house) to serve as stores, treasuries, and the like. The bronze gate of Nicanor led eastward again, down steps to the court of the women, where female Israelites in a state of purity were admitted. Priests and Israelites might enter the complex of house and courts by means of gates along the north and south walls; priests and Levites who were actively engaged in the service of the sanctuary tended to use the north side.

The complex we have so far described, which is commonly known as the sanctuary proper, circumscribed the God, the people, and the offerings of Israel. Within the boundaries of the sanctuary, what was known to be pure was offered by personnel chosen for the purpose in the presence of the people of God and of God himself. Nothing foreign, no one with a serious defect or impurity, nothing unclean was permitted. Here God’s presence was marked as much by order as by the pillar of cloud, which was the flag of the Temple by day, and the embers which glowed at night. God was present to the people with the things he had made and chosen for his own, and their presence brought them into the benefits of the covenantal compact with God. The practice of the Temple and its sacrificial worship was centered upon the demarcation and the consumption of purity in its place, with the result that God’s holiness could be safely enjoyed, within his four walls, and the walls of male and female Israel. In no other place on earth was Israel more Israel or God more God than in the sanctuary. A balustrade surrounded the sanctuary, and steps led down to the exterior court; non-Israelites who entered were threatened with death. Physically and socially, the sanctuary belonged to none but God, and what and whom God chose (and then only in their places).

The sanctuary itself was enclosed by a larger court, and the edifice as a whole was referred to as the Temple. On the north side, the pure, sacrificial animals were slain and butchered, and stone pillars and tables, and chains and rings and ropes, and vessels and bushels, were arranged to enable the process to go on smoothly and with visible, deliberate rectitude. The north side of the sanctuary, then, was essentially devoted to the preparation of what could be offered, under the ministration of those who were charged with the offering. The south side was the most readily accessible area in the Temple. Although Israelites outnumbered any other group of people there, and pious Jews entered only unshod, without staff or purse (cf. Berakhoth 9:5), others might enter through monumental gates on the south wall of the mount of the Temple; the elaborate system of pools, cisterns, and conduits to the south of the mount, visible today, evidences the practice of ritual purity, probably by all entrants, whether Jewish or gentile, into the Temple. Basically, then, the south side of the outer court was devoted to people and the north side to things; together, the entire area of the outer court might be described as potentially chosen, while the sanctuary defined what actually had been chosen. The outer court was itself held in the highest regard, as is attested architectur ally by the elaborate gates around the mount.

The Gospels describe the southern side of the outer court as the place where Jesus expelled the traders, and that is what brings us to the question of a dispute in which Pharisees were involved. The exterior court was unquestionably well suited for trade, since it was surrounded by porticoes on the inside, in conformity to Herod’s architectural preferences. But the assumption of Rabbinic literature and Josephus is that the market for the sale of sacrificial beasts was not located in the Temple at all but in a place called Hanuth (“market” in Aramaic) on the Mount of Olives, across the Kidron Valley. According to the Babylonian Talmud,[7] some forty years before the destruction of the Temple, the principal council of Jerusalem was removed from the place in the Temple called the Chamber of Hewn Stone to Hanuth. Around 30 C.E. Caiaphas both expelled the Sanhedrin and introduced the traders into the Temple, in both ways centralizing power in his own hands.

From the point of view of Pharisaism generally, trade in the southern side of the outer court was anathema. Purses were not permitted in the Temple, according to the Pharisees’ teaching,[8] and the introduction of trade into the Temple rendered impractical the ideal of not bringing into the Temple more than would be consumed there. Incidentally, the installation of traders in the porticoes would also involve the removal of those teachers, Pharisaic and otherwise, who taught and observed in the Temple itself.[9]

From the point of view of the smooth conduct of sacrifice, of course, Caiaphas’ innovation was sensible. One could know at the moment of purchase that one’s sacrifice was acceptable and not run the risk of harm befalling the animal on its way to be slaughtered. But when we look at the installation of the traders from the point of view of Hillel’s teaching, Jesus’ objection becomes understandable. Hillel had taught that one’s sacrifice had to be shown to be one’s own, by the imposition of hands; part of the necessary preparation was not just of people to the south and beasts to the north, but the connection between the two by appropriation. Caiaphas’ innovation was sensible on the understanding that sacrifice was simply a matter of offering pure, unblemished animals. But it failed in Pharisaic terms, not only in its introduction of the necessity for commerce into the Temple, but in its breach of the link between worshipper and offering in the sacrificial action.

The animals were correct in Caiaphas’ system, and the priests were regular, but the understanding of the offering by the chosen people appeared—to some at least—profoundly defective. The essential component of Jesus’ occupation of the Temple is perfectly explicable within the context of contemporary Pharisaism, in which purity was more than a question of animals for sacrifice being intact. For Jesus, the issue of sacrifice also—and crucially—concerned the action of Israel, as in the teaching of Hillel. His action, of course, upset financial arrangements for the sale of such animals, and it is interesting that John 2:15 speaks of his sweeping away the “coins” (in Greek, kermata) involved in the trade. But such incidental disturbance is to be distinguished from a deliberate attempt to prevent the collection of the half shekel, which would have required co ordinated activity throughout Israel (and beyond), and which typically involved larger units of currency than the term “coins” suggests.

Jesus shared Hillel’s concern that what was offered by Israel in the Temple should truly belong to Israel. His vehemence in opposing Caiaphas’ reform was a function of his deep commitment to the notion that Israel was pure and should offer of its own, even if others thought one unclean (see Matt. 8:2-4; Mark 1:40-44; Luke 5:12-14), on the grounds that it is not what goes into a person which defiles but what comes out (see Matt. 15:11; Mark 7:15). Israelites are properly understood as pure, so that what extends from a person, what one is and does and has, manifests that purity. That focused, generative vision was the force behind Jesus’ occupation of the Temple; only those after 70 C.E. who no longer treasured the Temple in Jerusalem as God’s house could (mis)take Jesus’ position to be a prophecy of doom or an objection to sacrifice.

Neither Hillel nor Jesus needs to be understood as acting upon any symbolic agenda other than his conception of acceptable sacrifice, nor as appearing to his contemporaries as being anything other than a typical Pharisee, impassioned with purity in the Temple to the point of forceful intervention. Neither of their positions may be understood as a concern with the physical acceptability of the animals; in each case, the question of purity is, What is to be done with what is taken to be clean?

Jesus’ interference in the ordinary worship of the Temple might have been sufficient by itself to bring about his execution. After all, the Temple was the center of Judaism for as long as it stood. Roman officials were so interested in its smooth functioning at the hands of the priests they ap pointed that they were known to sanction the penalty of death for gross sacrilege.[10] Yet there is no indication that Jesus was arrested immediately. Instead, he remained at liberty for some time, and was finally taken into custody just after one of his meals, the last supper (Matt. 26:47-56; Mark 14:43-52; Luke 22:47-53; John 18:3-11). The decision of the authorities of the Temple to move against Jesus when they did is what made it the final supper.

Why did they wait, and why did they act when they did? The Gospels portray them as fearful of the popular backing which Jesus enjoyed (Matt. 26:5; Mark 14:2; Luke 22:2; John 11:47-48), and his inclusive teaching of purity probably did bring enthusiastic followers into the Temple with him. But in addition, there was another factor: Jesus could not sim ply be dispatched as a cultic criminal. He was not attempting an onslaught upon the Temple as such; his dispute with the authorities concerned purity within the Temple. Other rabbis of his period also en gaged in physical demonstrations of the purity they required in the con duct of worship, as we have seen. Jesus’ action was extreme, but not totally without precedent, even in the use of force. Most crucially, Jesus could claim the support of tradition in objecting to sitting vendors within the Temple, and Caiaphas’ innovation in fact did not stand. That is the reason why Rabbinic sources assume that Hanuth was the site of the vendors.

The delay of the authorities, then, was understandable. We could also say it was commendable, reflecting continued controversy over the merits of Jesus’ teaching and whether his occupation of the great court should be condemned out of hand. But why did they finally arrest Jesus? The last supper provides the key; something about Jesus’ meals after his occupation of the Temple caused Judas to inform on Jesus. Of course, “Ju das” is the only name which the traditions of the New Testament have left us. We cannot say who or how many of the disciples became disaffected by Jesus’ behavior after his occupation of the Temple.

However they learned of Jesus’ new interpretation of his meals of fellowship, the authorities arrested him just after the supper we call last. Jesus continued to celebrate fellowship at table as a foretaste of the kingdom, just as he had before. As before, the promise of drinking wine new in the kingdom of God joined his followers in an anticipatory celebration of that kingdom (see Matt. 26:29; Mark 14:25; Luke 22:18). But he also added a new and scandalous dimension of meaning. His occupation of the Temple having failed, Jesus said over the wine, “This is my blood,” and over the bread, “This is my flesh” (Matt. 26:26, 28; Mark 14:22, 24; Luke 22:19-20; 1 Cor. 11:24-25; Justin, Apology, 1.66.3).

In Jesus’ context—the context of his confrontation with the authorities of the Temple—his words can have had only one meaning. He cannot have meant, “Here are my personal body and blood”; that is an interpretation which only makes sense at a later stage in the development of Christianity.[11] Jesus’ point was rather that, in the absence of a Temple which permitted his view of purity to be practiced, wine was his blood of sacrifice and bread was his flesh of sacrifice. In Aramaic, “blood” (dema) and “flesh” (bisra, which may also be rendered as “body”) can carry such a sacrificial meaning. And, in Jesus’ context, that is the most natural meaning.

The meaning of “the last supper,” then, actually evolved over a series of meals after Jesus’ occupation of the Temple. During that period Jesus claimed that wine and bread were a better sacrifice than what was offered in the Temple, a foretaste of new wine in the kingdom of God. At least wine and bread were Israel’s own, not tokens of priestly dominance. No wonder the opposition to him, even among the Twelve (in the shape of Judas, according to the Gospels), became deadly. In essence, Jesus made his meals into a rival altar.

That final gesture of protest gave Caiaphas what he needed. Jesus could be charged with blasphemy before those with an interest in the Temple. The issue now was not simply Jesus’ opposition to the sitting of vendors of animals, but his creation of an alternative sacrifice. He blasphemed the law of Moses. The accusation concerned the Temple, in which Rome also had a vested interest.

Pilate had no regard for issues of purity; Acts 18:14-16 reflect the attitude of an official in a similar position, and Josephus shows that Pilate was without sympathy for Judaism. But the Temple in Jerusalem had come to symbolize Roman power, as well as the devotion of Israel. Rome guarded jealously the sacrifices which the emperor financed in Jerusalem; when they were spurned in the year 66, the act was a declaration of war.[12] Jesus stood accused of creating a disturbance in that Temple (during his occupation) and of fomenting disloyalty to it and (therefore) to Caesar. Pilate did what he had to do. Jesus’ persistent reference to a “kingdom” which Caesar did not rule, and his repute among some as messiah or prophet, only made Pilate’s order more likely. It all was prob ably done without a hearing; Jesus was not a Roman citizen. He was a nuisance, dispensed with under a military jurisdiction.

At last, then, at the end of his life, Jesus discovered the public center of the kingdom—the point from which the light of God’s rule would radiate and triumph. His initial intention was that the Temple would con form to his vision of the purity of the kingdom, that all Israel would be invited there, forgiven and forgiving, to offer of their own in divine fellowship in the confidence that what they produced was pure (see Matt. 15:11; Mark 7:15). The innovation of Caiaphas prevented that by erecting what Jesus (as well as other rabbis) saw as an unacceptable barrier between Israel and what Israel offered.

The last public act of Jesus before his crucifixion was to declare that his meals were the center of the kingdom. God’s rule, near and immanent and final and pure, was now understood to radiate from a public place, an open manifestation of the divine kingdom in human fellowship. The authorities in the Temple rejected Jesus, much as some people in Galilee had already done, but the power and influence of those in Jerusalem made their opposition deadly. Just as those in the north could be condemned as a new Sodom (see Luke 10:12), so Jesus could deny that offerings coopted by priests were acceptable sacrifices. His meals replaced the Temple; those in the Temple sought to displace him. It is no coincidence that the typical setting of appearances of the risen Jesus is while disciples were taking meals together.[13] The conviction that the light of the kingdom radiated from that practice went hand in hand with the conviction that the true master of the table, the rabbi who began it all, remained within their fellowship.

[1] See Josephus, Jewish War, 2:197,409; Against Apion, 2:77; Philo, Embassy to Gains, 157, 317.

[2] See Mishnah, Shekalim, 1.1, 3.

[3] See his Jewish War, 7:218, and Antiquities of the Jews, 18:312.

[4] See Antiquities, 13:372, 373.

[5] See Jewish War, 1:648-55; Antiquities, 17:149-67.

[6] See the Babylonian Talmud, Bezah 20a, b; Tosephta Hagigah 2.11; Jerusalem Talmud, Hagigah 2.3 and Bezah 2.4.

[7] See Abodah Zarah 8b; Shabbath ISa; Sanhedrin 41a.

[8] See Mishnah Berakhoth 9.5.

[9] See the Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 11.2; Pesahim 26a.

[10] See Josephus, Antiquities, 15:417.

[11] For a scholarly discussion of that development as reflected within the texts of the New Testament, see Chilton, A Feast of Meanings: Eucharistic Theologies from Jesus through Johannine Circles (Leiden: Brill, 1994). In a popular way, the question is also treated in Chilton, “The Eucharist: Exploring Its Origins,” Bible Review 10 (1994), 6:36-43.

[12] See Josephus, Jewish War, 2:409.

[13] See Luke 24:13-35, 36-43; Mark 16:14-18 (not originally part of the Gospel, but an early witness of the resurrection nonetheless); and John 21:1-14.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue