Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 4

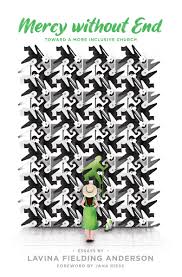

Lavina Fielding Anderson, Mercy Without End: Toward a More Inclusive Church

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the HTML format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. Also, as of now, footnotes are not available for the online version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version, the PDF provided at the bottom of this page, or the PDF on JSTOR.

Lavina Fielding Anderson’s new book, Mercy without End, is a collection of essays, mostly delivered as public presentations and later published, mostly in the 1990s, by one of the most erudite and articulate living women in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She brings the collection up to the present with a long introduction and a recent essay. The essays chronicle, in engaging fashion, many of the current issues for thinking Mormons as well as visiting and revisiting the cause célèbre that has come to define her public life: In 1993, Lavina Fielding Anderson, a faithful and active member, was excommunicated from the Church of her fathers and her father’s fathers for publishing an article in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought critical of the misuse of power by Church leaders against Church members and for refusing to repent of the action or apologize for the publication and to promise never to do such a thing again. The crime she had committed, she was told after the fact, was apostasy, defined as embarrassing the Church and the brethren. Her husband Paul, in a letter to the stake president, described Lavina’s deed as speaking “some unpleasant truths more loudly and clearly than Church leaders like to hear them” and giving a voice “to the quiet pain of friends and acquaintances who have been hurt” (6).

Because of this central event, I wish that the Dialogue article that prompted the action was reprinted in this collection. Diligent readers may find it as “The LDS Intellectual Community and Church Leadership: A Contemporary Chronology,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 26, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 7–64.

Unlike other members disciplined by their leaders, Lavina has not disappeared into the hinterlands or become a consistent dissenting voice. She has never left the Church, even as the Church has left her. Her Mormonness is deep and essential. She remains a faithful member of her LDS congregation in all manageable ways. For her twenty-seven years of exile she has continued to attend meetings, sing hymns, read scriptures, and engage in family prayer. She feels harmony with deity and with Church teachings, sometimes guided by a distinct voice. This dissident annually reads the Book of Mormon. She says that it takes about six weeks and gets the year off to a good start. Recent efforts for her rebaptism into the Church have been denied at high levels, apparently because she is not sorry or not sorry enough for shining light on questionable behavior. There is no question that this is a person of deep devotion, a person who shapes words skillfully and makes arguments with care. She values the holy words of the scriptures. She is aware and angry, but she is also at peace.

Among the themes she frequently visits are diversity and inclusion and then, of course, inclusion despite diversity. She skillfully crafts her essays with memorable images and metaphors. My favorite from many examples is that the Church leadership would like us to be similar, like blades of grass in a garden and the whole Church a beautiful, well-tended lawn. She dismisses that uniformity saying that “God doesn’t plant lawns. He plants meadows.” What we have from God is “the fundamental holiness of diversity” (185–86).

She recommends silently thinking and talking aloud in inclusive language terms whenever scriptures are involved or in talking about Church activities, in our songs and our prayers. She laments that women are excluded from our familiar religious speech. Her family always includes others when reading the scriptures and singing the hymns. Brothers and sisters, boys and girls. She wants our formal prayer language replaced with everyday speech. She reads the scriptures edited into contemporary language.

She writes that the Church promises many things that will come to you if you are good, but they don’t always come through. Situations are much more complex than expected. She notes that Church members are trained to be afraid even as they are trained to deny that there is anything to be afraid of. She says fear is used “as a mechanism of social control for both women and men in the church” who are committed members (207). She says that some members are categorized and demonized after which they can be punished, that silencing, reprisals, and intimidations are very real in the Church. She objects to the idea that leaders are more inspired than members. She says that free agency argues against the infallibility of leaders. She opposes the use of the temple recommend to coerce certain behavior.

She has much to say about the unequal treatment of women in the Church and notes how women are unjustly left out of the official discourse. She writes, “The mechanisms of patriarchy are embedded deep in our culture and our language. Inequity is wrong—ethically and morally wrong” (194). She says that the Church is a “socially constructed patriarchy.” She thinks that “as an institution, it is afraid of its own women.” That its men “in general are selfish and lazy enough to prefer being served by women to being partners with them, that these men lack the moral imagination to envision true partnership, and that they are genuinely ignorant of the pain they are inflicting on the women in their lives and the pain in which they are consequently living themselves” (226).

She says that women receive “constricting messages” from the Church. They are told that they have been “created for a purpose that serves the convenience of others, a purpose they were not consulted about and did not consent to (at least in this life), that God will punish them if they neglect their duty, which is to serve their families” (236). She observes that Mormon women are allowed to have strengths only if we use them to benefit others. She argues that the only way women can save themselves is to trust the voice within them.

Having been excommunicated, she describes feeling freer. “The fear is gone; and along with it is the burden of the rules and regulations and restrictions. It simply slipped off my back. . . . I no longer feel any need to evaluate my own righteousness or, more importantly, the righteousness of others according to the rules” (176). She has moved to a broader landscape, noting that the Church teaches many correct principles, “but I no longer believe that it teaches all of them nor do I believe that the church is the only place we should seek them.” So, where are they? She thinks that the Lord “expects us to identify those correct principles out of the floods and torrents of raw experience with which he drenches us daily—experiences of good and evil and every gradation in-between” (186).

Lavina’s mind and voice have been a trial to several layers of Church leadership. She is more articulate than most men, thinking and talking at levels they are not used to. She writes of people, personal experiences, diaries, and reminiscences. She records the mundane and the precious. She says we still have miracles and recounts some. She believes that all will be well. She says and believes that “the glory of Mormonism is its joyous affirmation of eternal human worth” (154).

She often takes an accepted aspect of Mormon life and turns it on its head in these thoughtful and well worked-out presentations. We would all do well to shape talks as good as these. She sets questions and answers them. Her essays are sermons, carefully crafted, embroidered, trimmed with fancy stitches.

And here for your homework are her seven suggestions for living with integrity, for living according to her principles in harmony with a church that has disowned her.

Develop more faith.

Grow a backbone. Don’t act against your conscience.

Do not mistake the medium for the message, the vessel for the content, the Church for the gospel.

We must learn to affirm covenant relationships with people even when they break contracts.

Learn to disagree without ceasing to love. We need to manifest patience, tolerance and good will to handle dissent.

Even though we are excluded and shunned we can remain attached to the church by offering the testimony of presence. (151–54)

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue