Articles/Essays – Volume 57, No. 2

Materializing Faith and Politics: The Unseen Power of the NCCS Pocket Constitution in American Religion

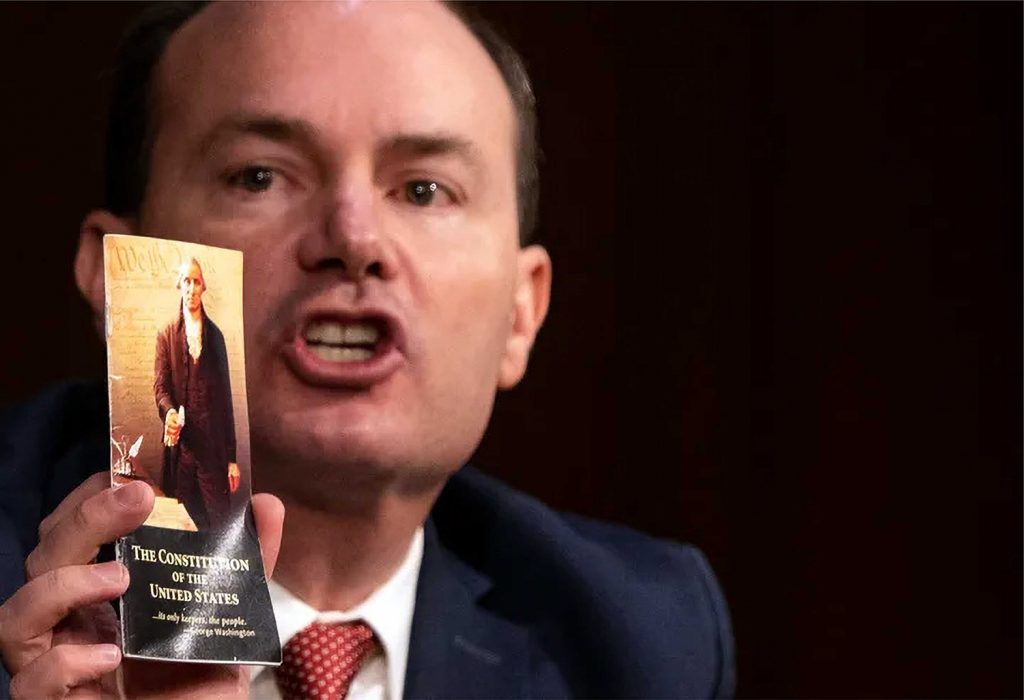

In 2014, Latter-day Saint painter Jon McNaughton painted a triumphal and patriotic, yet reverent, scene of Cliven Bundy on horseback, with one hand lifting an American flag and his hat covering his heart in the other. Peeking out from Bundy’s shirt pocket is a pamphlet with the likeness of George Washington with a penetrating glare contrasting Cliven’s prayer-closed eyes.[1] During the 2014 and 2016 Bundy standoffs, antigovernment militia and protestors ensured that they came armed with guns, ammunition, and pocket Constitutions. The version carried by the Bundys, published by the National Center for Constitutional Studies (NCCS), the former Freemen Institute (FI), is the same that Senator Mike Lee brandished during his speech at the US Senate hearings for President Trump’s 2020 Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett. Holding the pamphlet during the nationally televised session, Lee declared that “[the Constitution] is a thing that works, and works best when every one of us reads it, understands it.”[2] What are we to make of the prominence of this pocket Constitution in these scenes?

With more than fifteen million copies in circulation in the early twenty-first century, the pocket Constitution published by the NCCS has made headlines as politicians, antigovernment activists, and political commentators brandished it during protests and in the Senate Chamber of the US Capitol.[3] While the text of the Constitution in the booklet is proofed word for word against the original Constitution of the United States, the surrounding material is curated to imbue the Constitution with religious significance and a particular political ideology. Thus, this document is a valuable source to consider in the context of Christian nationalism in the United States. Further, it shows how a Latter-day Saint belief in a divinely inspired Constitution subtly made its way into wider American reception in the latter twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

This article argues that the NCCS pocket Constitution becomes a commanding piece of material religion, an object that does not only reflect a political philosophy or a theological belief but acts on its own and transforms through performance. In the latter part of the article, I suggest the idea of “the corporeality of the Constitution,” or simply that the materiality, the “stuff,” or the physical presence of a pocket Constitution allows the document to anthropomorphize, to act, and to perform independent of the person holding it. Scholars of material religion have suggested that things are essential aspects of religion, not simply additions or physical representations of it.[4] Indeed, while the pocket Constitution is more clearly understood by the sources that inspired it, as an object, it is not only an extension of a particular worldview but has the capacity to operate independent of it. Due to its power as material religion, the pocket Constitution ceases to exist as bound pages of printed text.

The NCCS Pocket Constitution

Beginning in the late 1980s, the NCCS began publishing a pocket version of the US Constitution. As early as 1987, and in connection with the bicentennial of the Constitution, NCCS pocket Constitutions were made available for purchase at the price of twenty-five cents.[5] Even in his official Church position as an apostle during the 1970s and 1980s, Ezra Taft Benson publicly supported the aims of the NCCS predecessor, the FI, to educate Americans about the “Judeo-Christian” roots of the United States and the divine quality of the Constitution as well as to distribute literature on these principles, including pocket Constitutions.[6] Appropriately, the non-Constitutional text included in the introductory material speaks to the NCCS mission of framing the US Constitution with an emphasis on individual liberty (free agency), limited government, and the religious origins of the charter.

In 1971, W. Cleon Skousen founded the FI in Provo, Utah. Skousen, who served as an FBI agent, a police chief in Salt Lake City, and a Brigham Young University professor, became one of the most recognized Latter-day Saint authors in the postwar period. The original name of the organization referred to the Book of Mormon’s “freemen,” a group of ancient Americans dedicated to “maintain[ing] their rights and the privileges of their religion by a free government,” as opposed to the “king men” who “were desirous that the law should be altered in a manner to overthrow the free government and to establish a king over the land.”[7] Established just past the midpoint of the Cold War, the FI’s purpose was “to give light to the world” and help people “be aware of the problems in the world today.”[8] In a 1975 speech in Ogden, Utah, Skousen claimed that Church President David O. McKay had asked him in 1967 to establish the FI in part to fulfill Joseph Smith’s purported prophecy that Latter-day Saint elders would save the Constitution that would “hang by a thread.”[9]

Skousen and Ezra Taft Benson were both outspoken critics of New Deal liberalism in the form of the expanding welfare state and, most importantly, the spread of communism. Fearing the manifestation of these problems in the United States, Skousen and Benson were just two of a growing set of conservative Americans determined to protect what they understood to be a nation established upon Judeo-Christian principles from the attacks of godless communism and deliberate slights to their understanding of Latter-day Saint “free agency.”[10] Throughout the 1970s, Skousen and the FI conducted dozens of lectures on the Constitution and its divine roots to thousands of Americans across the country and to more than fourteen countries around the world.[11] Skousen and the FI’s reputation as an influence in Utah politics quickly gained momentum as their patronship helped elect Orrin Hatch to the US Senate in 1976.[12]

In November 1984, the FI changed its name to the NCCS and moved its official headquarters from Salt Lake City to Washington, D.C.[13] This change was likely part of an effort to align more closely with the emerging religious right during the Regan administration.[14] Even though Latter-day Saint leaders and a large proportion of members were aligned with evangelicals on the religious right on issues such as abortion, communism, and the Equal Rights Amendment, many evangelicals grew more and more concerned about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Southern Baptists, in particular, were worried about the LDS Church’s growth in the American South.[15] However, despite concerns within the Moral Majority and the emerging religious right during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Latter-day Saints found success in Washington, D.C., as the Reagan administration filled its ranks with a number of Latter-day Saint professionals.[16] Skousen and the NCCS garnered admiration from Reagan thanks to Skousen’s “fine public service” in his efforts and the efforts of the NCCS to instruct Americans on the importance of the Constitution.[17] During these years, Skousen found success in allying himself and the NCCS with leaders and forums associated with the religious right and was granted access to leadership positions within their institutions.[18] Skousen also worked with Jerry Falwell, who praised Skousen as “the conservative answer to the Brookings Institute.”[19] Additionally, the Salt Lake Tribune reported that members of the Moral Majority were enrolled in Skousen and the FI’s “Miracle of America” seminars in the early 1980s, evidence of how a distinctly Mormon nationalist worldview made its way into larger religious conservative audiences.[20]

Skousen’s nephew, Joel Skousen, confirmed in a 1985 Sunstone magazine article that trepidation by evangelicals to affiliate and work with the FI due to its Latter-day Saint affiliation was indeed a reason for the name change. The article quoted Joel Skousen that “having a Salt Lake address” undoubtedly led to “Mormon identification,” which at the time was less than desirable due to “real backlash” in the fundamental and evangelical communities. Skousen attributed this backlash in part to the recent anti-Mormon Ed Decker film, The God Makers, which skewed realities of Latter-day Saint practices and doctrine but was widely distributed and shown to large audiences of evangelicals across the United States.[21] Beyond the organization’s motivations in making its public appearance more appealing to wider American Christian audiences, Skousen had distinct beliefs about the role of religion in the United States.

The FI/NCCS claimed to teach Americans “Constitutional principles in the tradition of America’s Founding Fathers.”[22] In its periodical bulletin and monthly publication the Freemen Digest, the FI/NCCS regularly published articles on what they believed the “founders” envisioned for the United States. Central to “the Founding Fathers’ Constitutional formula” was “The Secret to America’s Strength,” religion, and, implied in that, Christianity. Skousen further wrote that “the Founders felt the role of religion would be as important in our own day as it was in theirs” and that “religion is the foundation of morality.”[23] From the beginning, religious nationalism guided the FI/NCCS.

For example, the July 1978 issue of the Freemen Digest featured a series of articles on the establishment of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The texts of those documents and an analysis of each by James Mussatti are framed by a crisis, described by editor Michael Chadwick as a “retreating away from the economic principles and political precepts which had been established by the Founders” as early as the 1930s.[24] Presumably, Chadwick was referring to the Roosevelt administration in the 1930s and the expansion of the New Deal during the Great Depression. Writing within the context of a conservative reaction to President Jimmy Carter’s administration in the late 1970s, the FI warned that “if in the near future we are going to step forth and restore the Constitution, we must become fully conversant and wholeheartedly converted to the high principles contained in the inspired Constitution and the free institutions which it originally prescribed.”[25] Instead of reproducing the founding documents and letting them speak for themselves, the FI included the Mussatti analysis that frames them as “The Inspired Declaration of Independence” and “The Inspired Constitution” followed by the original texts.[26] Appropriately, the issue’s back cover contains a single quote by George Washington from his first inaugural address: “No People can be bound to acknowledge and adore the visible hand, which conducts the Affairs of men more than the People of the United States. Every step, by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation, seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency.”[27] This practice of framing the text of the founding document with religious language acts as a forerunner for what the NCCS later did with the pocket Constitution. The role of religion remains an important pillar of the NCCS today as it continues to sacralize the US Constitution as a product of divine intervention.

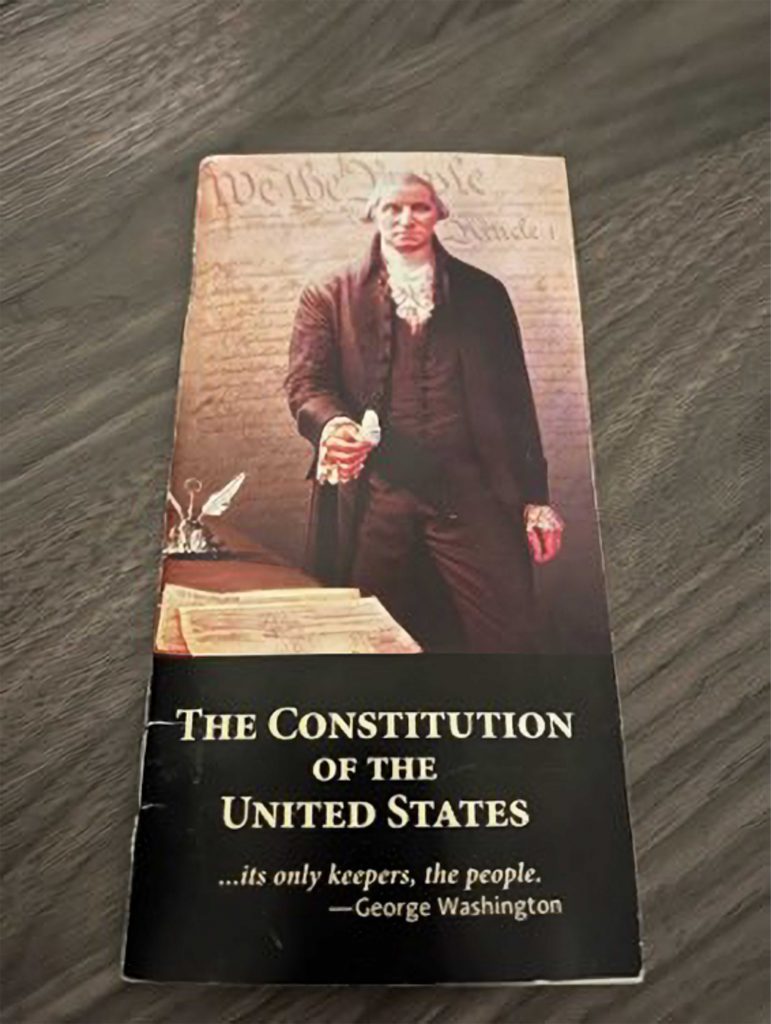

The cover of the NCCS Constitution booklet (figure 1) features a portrait of George Washington by Austrian-American painter Robert Scholler, who painted the portrait in 1987 to commemorate the bicentennial of the Constitution “to remind Americans of their responsibility for the Constitution and the freedom it brings.”[28] In the painting, George Washington offers the viewer a quill pen. The gesture suggests that the viewer signs the Constitution in the painting’s foreground as part of a recommitment to the text. Scholler’s original rendering included a pledge sheet under the canvas that viewers could sign “stating that they have read or will read the Constitution and uphold its principles.”[29] The NCCS booklet incorporates a similar move on its back cover. As the reader finishes the booklet, they are faced with the following pledge: “I, as one of We, the People of the United States, affirm that I have read or will read our U.S. Constitution and pledge to maintain and promote its standard of liberty for myself and for my posterity, and do hereby attest to that by my signature.” Under this statement is a blank line for the reader to sign, and beneath that signature line is Washington’s signature with the label: “George Washington, Witness.”[30] The inset of the cover and first page of the booklet contains quotes from George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and the Federalist handpicked to give the sense that these founding individuals supported modern notions of constitutional originalism: “[let us] carry ourselves back to the time when the Constitution was adopted”; limited government and individual sovereignty, “influence is no government”; and divine intervention in the founding of the Constitution, “the event is in the hand of God.”[31] The final quote, attributed to George Washington, serves as an introduction to an opening section of “selected quotations” that preface the Constitutional text.

Figure 1. Front and back covers of the pocket Constitution published by the NCCS, in possession of author.

The first batch of “selected quotations” is titled “Observing the Hand of Providence.” Thus, the pocket Constitution shapes the reader’s experience to see religious significance as soon as the reader begins to make their way through the booklet. Tellingly, this section of quotations comes before the others titled “Preserving the Principles,” “Guarding Virtue & Freedom,” and “Educating the People,” suggesting that the Constitution’s divine origins are fundamental to understanding the other framing quotations. As with the booklet’s opening pages, Washington is again cited as explaining that events surrounding the adoption of the Constitution “demonstrate as visibly the finger of providence as any possible event in the course of human affairs can ever designate it.”[32] While not referenced as such, the statement is from a May 28, 1788, letter from George Washington to Marquis de Lafayette detailing the process of ratifying the new federal Constitution.[33] Indeed, Washington’s letter proposes a supernatural intervention in the divisive and tense ratification process that followed the Constitutional convention. This context is important for understanding Washington’s appeal to providence. Without it, the quotation may mislead as it could be interpreted that Washington was speaking specifically to the drafting of the Constitution or the 1787 Convention, rather than the “change in men’s minds and the progress toward rectitude in thinking and acting” that Washington detailed to Lafayette during the ratification deliberations.[34] Taking Washington’s words out of context erases the reality of an incredibly diverse American political landscape that was the setting of the Constitutional Convention and ratification process of the closing years of the 1780s. A tendency for conservative organizations like the FI and NCCS is the assumption that the founding generation can be reduced to one voice and perspective. But as constitutional and American political historians have shown, this is simply not the case.[35]

The next quotation from the “Observing the Hand of Providence” section is from Daniel Webster, a nineteenth-century contemporary of Joseph Smith: “I regard it [the Constitution] as the work of the purest patriots and wisest statesmen that ever existed, aided by the smiles of a benignant [gracious] Providence . . . it almost appears a Divine interposition in our behalf.”[36] The booklet again does not cite the quotation and lets it stand alone without context. Webster’s statement came from a June 1837 speech delivered at a public reception in Indiana.[37] Webster gave his speech during the early months of the Panic of 1837, a monetary crisis that launched a depression, and within the context of what historian Brooks D. Simpson termed the “Cult of the Constitution.” Simpson explains that Webster was successful at oratory in part due to “his eloquence in expounding the nature and purpose of . . . the United States Constitution” and speeches that “crafted an image of the Constitution designed to further his ends, presenting it as a master plan which outlined the boundaries and limits of change while giving direction and embodying order.”[38] While Webster’s sentiment concerning a divinely inspired Constitution appears accurately represented, the NCCS booklet does not account for Webster’s context.

The final section of the pocket Constitution is an advertisement page that markets other publications from the NCCS. Among those presented are The Five Thousand Year Leap and The Making of America, both written by W. Cleon Skousen and published by the NCCS in the 1980s. The Five Thousand Year Leap places the history of the United States along a grand eschatological vision and timeline. For example, Skousen argues that “the Founders considered the whole foundation of a just society to be structured on the basis of God’s revealed law.”[39] Ultimately Skousen contends that revealed laws from God constitute the foundation for most laws in the world but that they were slowly but steadily perfected through the English Common Law and then into the US system, underpinned by “Judeo-Christian” principles. Further, Skousen incorrectly adds that “the Founders were not indulging in any idle gesture when they adopted the motto, ‘In God we trust.’”[40] Despite some usage in the eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, “In God We Trust” was not officially adopted during what Skousen would consider the founding generation of Americans.[41]

Similarly, The Making of America is an American history textbook that became the subject of scrutiny in the late 1980s with its inclusion of racist slurs and the conclusion that “slavery is not a racial problem. It is a human problem.”[42] Of interest here are two other books titled The Real George Washington: The True Story of America’s Most Indispensable Man and The Real Thomas Jefferson: The True Story of America’s Philosopher of Freedom. Even the titles of these NCCS publications reveal the organization’s intentions and epistemological base. The modifier “real” before the names of the two American presidents suggests a need to set the record straight, to clarify who these people “really were,” and to fight back against prevailing trends in academic scholarship during the period.

In May 2010, conservative political commentator and Latter-day Saint Glenn Beck praised The Real George Washington (published 1991) on his Fox News show as part of his “Founders’ Fridays” series. Beck labeled the book “the best book ever written on George Washington” and proceeded to interview his guests, a coauthor of the book, Andrew Allison, and then-president of the NCCS, Earl Taylor. Allison explained the “presumptuous” title came about because “instead of trying to interpret him for the scholars, we went out of our way to let him speak for himself, so that the American people, including young people, could find out who he is.” Taylor later in the program boasted that the book contained the word “providence,” as used by Washington, eighty-eight times. Allison continued this theme and claimed that “virtually, all of them [the founders] said that the reason that this country was created was because of the intervention of God. And nobody said it more often or more effectively than George Washington.”[43] In this interview, Allison aligned well with the goals of the NCCS to instruct the public about the religious influences that led to the establishment of the Unite States. Further, Allison’s comments reveal one of the primary motivations in writing the 1991 biography: to show that the “real” George Washington believed that God inspired the American founding.

Christian nationalist myth-making in the United States has often taken the form of imbuing historical individuals and groups with a heightened sense of Christian religiosity, even those criticized by their contemporaries as deviating from acceptable “confessional piety.”[44] As seen in the case of the pocket Constitution, a piece of Washington’s supposed religiosity by using the word “providence” attempts to demonstrate the he was both directed by God during the founding era and acknowledged the divine. According to Steven K. Green, these religious nationalists fail to recognize that “religious imagery and symbolism were the common idioms that all speakers employed when making rhetorical points.” As politicians, these individuals were effective communicators and understood the popular language of their time. Indeed, Green notes “that one can find references to God or scripture in the political writings of the era is thus unremarkable.”[45] This is not to say that Americans, even those well-known such as Washington and Webster, did not hold religious sympathies. Rather, it is context that sheds light on the arguments put forward by those that insinuate that the founders established the United States as a Christian nation based simply upon the use of religious language.

A Divinely Inspired Constitution: Latter-day Saint Views of the United States Constitution

“I have established the constitution of this Land, by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose and redeemed the Land by the shedding of blood,” spoke God in Joseph Smith’s 1833 revelation.[46] As Jan Shipps has demonstrated, the 1833 revelation was produced during a time when “the people of the United States were busily engaged in the manufacture of instant heritage, substituting inspiration for antiquity with regard to the Constitution.”[47] Smith and his Latter-day Saint following believed that God establishing the United States was akin to establishing sacred geographic and political structural space for Smith’s religious innovations.[48]

The 1833 revelation contains several principles related to American religious nationalism, including the explicit notion that God personally brought about the US Constitution and, by implication, that God inspired the “wise men” who drafted it. Latter-day Saints, like Joseph Smith, were not alone in this line of thinking. Religious nationalists from an assortment of movements such as Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Unitarians, and Transcendentalists were invested in the idea of the United States as having a sacred role in human history, especially its founding documents.[49] The revelation’s evocation of redemption of land by blood connects to a trope common among Christian nationalist narratives of defending land through physical sacrifice, often violent sacrifice.[50] In the generations following Joseph Smith, the revelation has been understood as referring to the American War of Independence.[51] Furthermore, Smith’s revelations connecting to the American landscape aligns with the Book of Mormon’s chosen and “promised” land narrative, which has subsequently been interpreted by many Latter-day Saints leaders as the United States.[52] Sacred geography and boundary making have a long history in both Latter-day Saint history of settlement and migration and broader American Christian nationalist views of Manifest Destiny, foreign policy, imperialism, and immigration.[53]

The need to clearly delineate and defend boundaries draws from a feeling of threat. This connects to another tenet of the Book of Mormon’s narrative of a potential downfall of the promised land. The land only remains promised if those to whom it was promised hold up their end of the bargain through righteous living. As Philip Barlow notes, “These who fail become unchosen.”[54] Sin separates the chosen people from their inheritance, thus the need to police its physical and moral boundaries.

Land is not the only thing at risk in this Mormon-nationalist vision. An 1840 Joseph Smith sermon recorded by Martha Jane Knowlton Coray is an important touch point for a Mormon claim to uniqueness in the material history of the Constitution. Smith’s sermon predicted that “this nation [the United States] will be on the very verge of crumbling to pieces and tumbling to the ground and when the constitution is upon the brink of ruin this people [presumably the Church] will be the Staff up[on] which the Nation shall lean and they shall bear the constitution away from the <very> verge of destruction.”[55] In Latter-day Saint culture, this idea of the Constitution in peril has been understood, oftentimes inappropriately, under the wide-umbrella term “the White Horse Prophecy.”[56] In any case, these prophecies are influential sources of Mormon American exceptionalism, including how the physical, material Constitution became an icon of this idea in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Joseph Smith indeed had a unique view of the United States and its Constitution. When discussing Smith’s views of the Constitution, it is important to consider his disappointment in its shortcomings, specifically in protecting religious liberty and delivering justice upon those that violated it. Joseph Smith did not view the document as a stagnant, complete, or perfect document. Though Smith wrote that “the Constitution of the United States is a glorious standard; it is founded in the wisdom of God. It is a heavenly banner,” one should remember that he dictated those views while imprisoned in Liberty Jail in the spring of 1839.[57] Smith believed that the Constitution was erected to protect religious liberty but also acknowledged its deficiencies, especially as he was imprisoned from November 1838 to April 1839 due in part because of religious intolerance in antebellum Missouri.[58] For Smith, the Constitution was divinely inspired. But part of its divinity was its adaptability. Smith advocated amending the Constitution if it lacked in protections and power to enforce the rights of religious minorities.[59]

In the context of religious persecution in the 1830s and 1840s, Joseph Smith and other Latter-day Saints began to articulate a concept of theodemocracy as an adaptation of the Constitution’s approach to earthly governance and relationship with the divine. According to historian Nathan Jones’s characterization of Smith’s “alternative to American democracy,” theodemocracy “was premised on the expectation that the citizens of Zion would use their free will to voluntarily unify behind God’s will, as he transmitted to them through his prophets.”[60] In Smith’s estimation, democracy and republican forms of government only worked when those who participated were righteous and aligned their own desires with those of God.[61] Patrick Mason has identified the balance of sovereignty between God and the people as “Smith’s ideal government.” Smith and his followers believed that “only in such a society would inalienable human rights, dignity, and freedom be protected.”[62] Theodemocracy would not look like a pure democracy that appealed to the will of the public majority nor the divine edicts of an “aristocracy of clerics, as God’s regents.” Instead, to Smith, “God and the people held power jointly.”[63] Thus, theodemocracy countered the ill excesses of both republicanism and theocracy because it relied upon the virtue of the people who participated in the political process.[64] Understandably, this religiopolitical conception would face difficult realities. How would the system perfectly balance the interests of the theos and the demos? In Patrick Mason’s assessment, nineteenth-century Mormonism “assigned ultimate meaning and power to the sacred and . . . placed . . . high priority on conforming to the revealed decrees of God’s chosen messengers, demos clearly played a subservient role to theos.”[65] No clearer was this negotiation evident than when Joseph Smith directed the Nauvoo Council of Fifty to “draft a constitution that featured those principles they felt the US Constitution lacked,” as historian Benjamin E. Park has demonstrated, including a passed motion to declare Smith “’Prophet, Priest & King’” in the new theocratic-democratic blended government.[66] This renegotiation that places a higher status to theos over demos is also clear in the packaging of the NCCS pocket Constitution.

Joseph Smith’s successor, Brigham Young, felt similarly to Smith about the Constitution. In 1854, Young expressed that when it came to the founding generation, signers of the Declaration and framers of the Constitution were “inspired from on high to do that work” but also that the Constitution was not perfect.[67] Young and his Latter-day Saint contemporaries in the mid-nineteenth century felt that the evolution of the Constitution was necessary. More importantly, Saints from the Utah territorial period believed that the nation was corrupt and that God would punish America because of its treatment of Latter-day Saints.[68]

While the nation and American culture would inevitably degrade and fall from God’s favor, Latter-day Saints still believed in the divinity of the Constitution. This included the belief in restoring it, as per Joseph Smith’s prophecy, in helping it to fulfill its divine function as a protector of religious freedom and as something that would eventually be replaced by the imminent return of Jesus Christ with the institution of a Kingdom of God on Earth.[69] Latter-day Saints remained faithful to the Constitution, despite persistent attacks on the Mormon practice of plural marriage through the remainder of the nineteenth century. Historians have shown how Mormons “Americanized” following the 1890 Wilford Woodruff Manifesto that nominally put an end to polygamy. Most Americans then considered Latter-day Saints assimilated into the American cultural mainstream by the mid-twentieth century.[70]

J. Reuben Clark, who became a counselor in the Church’s highest governing body, First Presidency, in the early 1930s, heavily influenced Latter-day Saint discourse on the Constitution in the early to mid-twentieth century.[71] In the 1930s, Clark became an outspoken critic of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal policies. Much in part to Clark’s influence and efforts, the Church developed a self-sufficient welfare plan designed to help Latter-day Saints rid themselves of federal monetary assistance.[72] As with Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, Clark did not necessarily think the Constitution was a perfect document, despite its divinity.[73] Though Clark left room for the Constitution’s adaptation, such adaptation was only appropriate within the aims of his and other conservatives’ political worldview.

A staunch conservative, Clark often praised the US Constitution in church and public settings. During the Eisenhower administration, Clark’s views aligned well with a growing trend to posit the United States as a Christian nation.[74] However, Clark continued a unique Latter-day Saint tradition of reverencing the Constitution as a divinely inspired document, a nod toward its authority and its equation with Latter-day Saint scripture. In a 1957 address, Clark declared that the Constitution was “an integral part of my religious faith. It is a revelation from the Lord.”[75] Clark’s views about the inherent religiosity of the United States also fall into line with some of the motivations behind the new addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and the adoption of “In God We Trust” as a national motto: to combat atheistic communism. This political and cultural thrust of “Christian libertarianism” began in the 1930s and 1940s as corporations adopted Christian language to advance their capitalist interests in response to the New Deal.[76] Christian free enterprise, a blending of Christianity and libertarian free market advocacy, developed through the twentieth century.[77] The ideals of self-sufficiency, lack of governmental intervention in the market, “family values,” Christian-condoned mass consumption, and a defense against atheistic communism drove this cultural strand among what would become the New Right and Moral Majority of the 1970s and 1980s.

The most ardent anticommunist to come through the ranks of Latter-day Saint leadership was Ezra Taft Benson (1899–1994), who became a Church apostle in 1943 and eventually the Church president in 1985. Benson believed that members of the Church were destined to save the Constitution from the destructive hands of liberal Americans and the threats of socialism and communism.[78] In 1952, the Eisenhower administration tapped Benson to serve as secretary of agriculture. The First Presidency, which consisted of McKay, Clark, and Stephen L. Richards, gave Benson a special blessing to prepare him to fight communism during his presidential cabinet service.[79] Benson went on to level heavy critiques against progressive policies and supposed communist influences in the United States, including within Eisenhower’s administration.[80]

In 1959, Church President David O. McKay encouraged Latter-day Saints in General Conference to read W. Cleon Skousen’s 1958 book The Naked Communist, calling it an “excellent book.”[81] Benson gave a similar endorsement calling it a “timely book.”[82] Skousen’s work, including The Naked Communist, was widely read among anticommunist organizations, such as the John Birch Society and the All-American Society, the latter of which was founded in Salt Lake City in 1961.[83] The Naked Communist outlines a communist plot to take over the world’s governments and essentially enslave humanity according to the precepts of Soviet communism.[84] Not only did McKay endorse Skousen’s book, but he had also asked him to write it.[85] As ninth president of the Church, David O. McKay directed the Church from April 1951 until his death in January 1970. As such, his near-two decades of leadership coincided with some of the major developments in American anticommunism during the early decades of the Cold War. McKay’s views on communism were not unlike other Americans during this period, and he held views like other Latter-day Saint leaders on the divine purposes of the Constitution.[86]

As a counselor in the Church’s First Presidency in 1939, McKay explained that second only to worshiping God, “there is nothing in this world upon which this Church should be more united than in upholding and defending the Constitution.”[87] While he was serving as second counselor, the First Presidency issued its official statement on communism, one that he and other leaders would regularly cite in the coming decades: “Since Communism, established, would destroy our American Constitutional government, to support Communism is treasonable to our free institutions, and no patriotic American citizen may become a communist or supporter of communism. . . . Communism being thus hostile to loyal American citizenship and incompatible with true Church membership, of necessity no loyal American citizen and no faithful Church member can be a Communist.”[88] Thus, McKay and the First Presidency aligned with a growing dichotomous relationship between the US Constitution and communism, with a God-inspired system and a Satanic plot underlaying each.[89] Two aspects fundamentally defined the Church’s opposition to communism: state-established atheism and the denial of free agency.

To Latter-day Saints during the mid-twentieth century, the fear of communism struck at the Church’s most treasured principles. Foremost among these was the concept of free agency, the idea that central to one’s purpose in mortality is making righteous decisions without being compelled to do so by an outside force.[90] Latter-day Saint scripture holds that “men are free according to the flesh . . . and they are free to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil.”[91] Latter-day Saint voices, such as Benson and Skousen, powerfully combined the doctrine of free agency and libertarianism in a way that made them look inseparable.[92] This language on the principle of free agency has become intertwined with the patriotic rhetoric concerning American ideals of “life” and “liberty,” making the connection between the United States and its Constitution as necessary elements for the establishment of Mormonism that much easier to make.

A Performing Pocket Constitution on the National Stage

With the necessary context to understand the religious and political forces that underpin the NCCS pocket Constitution, this section seeks to bring to light the pamphlet’s implications when featured on the national stage. The visible nature of the pocket Constitution in the media places it within view of millions of people instantly. The NCCS pocket Constitution first came under wide scrutiny in 2013 when the state of Florida halted the purchase and distribution of it as part of a statewide civics program. Florida officials had purchased eighty thousand copies of the pocket Constitution and sent them to public schools across the state.[93] The purchase, which totaled $24,150, was heavily criticized by the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida and by Florida Supreme Court Justice Fred Lewis who ordered the cessation of distribution. Lewis acted in the wake of an article by the Tampa Bay Times that described the NCCS mission and historical context, including its view of the relationship between church and state.[94] While its time in the Florida education system was short, the fact that it was initially approved suggests either a willingness to support the pocket Constitution’s framing or its subtle ability to make its way into places of influence.

The last decade saw multiple examples of how the legacy of the NCCS pocket Constitution has made its way into the national consciousness. First, during the 2014 and 2016 standoffs between the federal government and the Bundys, Ammon and Cliven Bundy ensured that the pocket Constitution made its way into the national media coverage of the event, with the NCCS pocket Constitution always within their shirt breast pocket. In this instance, the NCCS Constitution came to embody a particular nationalist apocalyptic and western (regional) libertarian interpretation of both the Constitution and the Latter-day Saint faith. A final striking example considered here, introduced at the beginning, was Mike Lee brandishing the pocket Constitution in the US Senate Chamber during the October 2020 Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court then-nominee Amy Coney Barrett.

Like so many Latter-day Saints, Cliven Bundy believes in a divinely inspired Constitution. However, it is not clear that many Latter-day Saints believe, as Bundy does, that Jesus Christ himself authored the Constitution.[95] Bundy’s equation of the Constitution with direct revelation from God evokes distinctly Latter-day Saint ideas about the role and nature of the founding document. For Cliven Bundy, his family, and his likeminded associates, the Constitution holds a special material and ideological power.[96] Beyond simply subscribing to a particular worldview and interpretation of the Constitution’s content on the role of government, the Bundys perform what I call the “corporeality of the Constitution.” By this, I argue that in certain situations, such as the 2014 and 2016 Bundy standoffs, the physical pocket Constitution does not only represent a distinct religiopolitical worldview but begins to act on its own as an object that performs itself. As the actors wield the Constitution toward the popular media—especially through photographs—it becomes an actor itself, alongside those that believe in what it represents.

In April of 2014, Cliven Bundy and a group of like-minded antigovernment agitators engaged in a confrontation with the US Bureau of Land Management. From the government’s point of view, the dispute came down to Bundy, a Nevada cattle rancher, not paying his grazing fees and use of federal land. For Bundy, the dispute was rooted in a fundamental political and theological problem that pitted himself and other ranchers against an overreaching and godless government that sought to strip them of their rights as Americans and overstepped its constitutionally granted powers to manage public lands. The standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada, received widespread national media attention. The NCCS pocket Constitution featured prominently in photographs and interviews that sought to present these events to the public.

In January 2016, Ammon Bundy and various rightwing militia groups (including Citizens for Constitutional Freedom) occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. This episode featured the most cameos of the pocket Constitution. From the beginning of the occupation, Ammon Bundy assured that concerns about the material and conceptual fate of the Constitution were central to his messaging. In a YouTube video posted on January 1, 2016, Bundy appears sitting at a table in his home in his usual brimmed hat and plaid shirt, with the NCCS pocket Constitution peeping from his shirt pocket. In the video posted prior to the armed takeover of the wildlife refuge, Ammon explains that if he and the other ranchers did “not stand we will have nothing to pass on.” He further evoked previously discussed Mormon prophecies about the Constitution, explaining that it was “hanging by a thread” due to “blatant violations” by the federal government.[97]

Ammon Bundy received this worldview, and subsequently propagated it, thanks to his father Cliven’s radical Christian libertarian political philosophy infused with Mormon doctrine. The most potent source of this worldview is found in a scrapbook of sorts called the Nay Book, named after its compiler, Keith Nay, one of Bundy’s neighbors. The Nay Book is a manifesto of sorts that justifies antigovernment actions, couched in religious rhetoric and supported by statements from Latter-day Saint leaders, notably Ezra Taft Benson. Journalist Leah Sottile, who was granted access to it, explained that to its adherents, the Nay Book “provided proof of the link” between the Bundys’ religiopolitical philosophy, their antigovernment activities, and their affiliation as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[98] In a vernacular text that meshes holy writ (from the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, etc.) with prophetic statements, and infused with a distinct Western American libertarian philosophy, the Nay Book provided a rationale for standing up to the federal government. A central tenet to this worldview is an understanding that Latter-day Saints have a special responsibility to protect the divinely inspired Constitution from diabolical attack.

The NCCS pocket Constitution—whether tucked away yet visible in a protestor’s shirt pocket or waved violently alongside chants—was symbolic. Its presence was similar to how media and theater studies scholar Lindsay Livingston described the weapons that the Bundys and their compatriots brandished on I-15 during the 2014 standoff: “The guns themselves actually performed.”[99] Those who brandish the pocket Constitution do not need to explain why they are doing so as the visual presentation of it communicates the message—here is the document that represents our goals, our families, and our religiopolitical worldview. The NCCS pocket Constitution is in “a state of performative becoming,” as it evokes usage in the past and suggests it will be used in the future.[100] It acts as a reminder of a sacred history of which its possessor holds “insider status.” In other words, the one brandishing the pocket Constitution has insider knowledge about the “true” purpose and nature of the Constitution, including that they possess lost truth about its Christian heritage and principles.[101] The NCCS Constitution evokes notions of a redemptive future or the need to redeem what has been lost—the sacred past and insider knowledge that has been ripped away by “secularists,” “leftists,” or any other individual or group that tries to divorce the Constitution from its “original” and “true meaning.”

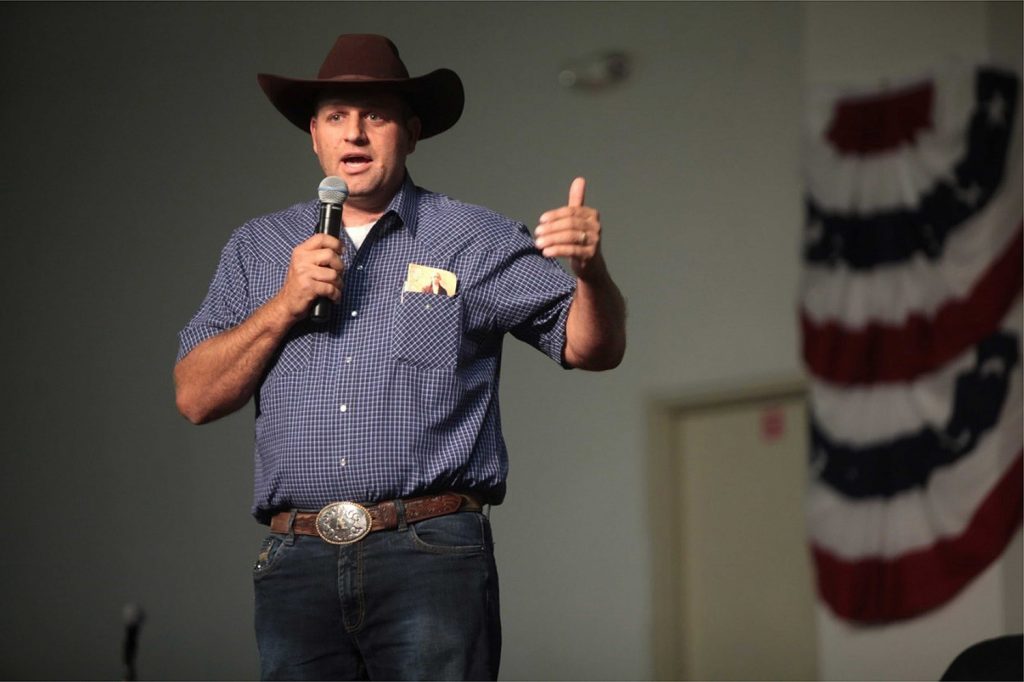

A quick sampling of media in response to the 2016 protests shows how the pocket Constitution became a Bundy character of its own. In addition to Ammon Bundy’s January YouTube video, an array of national media featured it. For example, the primary photograph accompanying a January 2016 Los Angeles Times article depicts Jon Ritzheimer, dressed in a militia jacket, sitting in the driver’s seat of a vehicle with an iPhone showing a picture of his family in one hand and the NCCS pocket Constitution in the other (figure 2).[102] This fascinating juxtaposition suggests that for Ritzheimer, family and Constitution are equally valuable motivations to signal to the world as he prepares for spiritual and political battle. He also evokes the image of a law enforcement officer flashing their badge to present identification along with authority, implying justification for whatever is to follow. Ritzheimer, a former marine, posted a video like Bundy’s the month before the armed takeover in which he explained his future involvement while waving the pocket Constitution to the camera.[103]

Other photographs show leader Ammon Bundy with the head of George Washington on the Constitution pamphlet peeking out from his jacket breast pocket (figure 3).[104] The parallel gazes from Ammon Bundy and the likeness of Washington elevate the pocket Constitution’s presence as if Washington himself were captured in the photograph. These images, and dozens of others, demonstrate that the pocket Constitution became a symbol of, and also an actor in, the Bundy cause. Imagining its absence is difficult because of how tightly associated the pocket Constitution became with the Bundys’ worldview and activities.

Through obvious antigovernment activities and media posturing, the Bundys imbue the pocket Constitution with special material power. It becomes corporeal—substantial, present, and concrete—not simply a booklet of paper pages but a demanding physical presence with potentially violent associations. With the pamphlet’s dominating portrait of Washington, the Constitution becomes anthropomorphized—with Washington himself embodying the Constitution. Further, this idea of a corporeal Constitution becomes even more evident in the context of Latter-day Saint prophecies concerning its fate and threatened destruction. The idea of the Constitution “hanging by a thread” suggests the physical materiality of the document. While understood as metaphor—saving the “idea” or “concepts” of the Constitution—the Bundys emphasize the materiality of the Constitution as a physical, tangible thing. The choice on the part of the Bundys to physically wave, pocket, and brandish the pocket Constitution grants the document a life of its own.

This practice occurs in other public performances as well. In his opening speech discussing the nomination of Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett on October 12, 2020, Senator Mike Lee held up a NCCS pocket Constitution and enthusiastically proclaimed, “This is a thing that works, and works best when every one of us reads it, understands it, and takes and honors an oath to uphold it and protect it and defend it. When we do our jobs in this branch, when our friends in the executive branch do their jobs, it requires us to follow the Constitution just the same way” (figure 4).[105] To some or most observers, Mike Lee’s role in invoking the NCCS pocket Constitution on national television is benign and unnoteworthy. However, despite the defense of Lee’s spokesperson Conn Carroll that Lee “was not aware” that he was holding the NCCS version, the Utah senator’s affiliation with both the messages in the pocket Constitution itself and its publisher is no accident.

After Mike Lee won Utah’s junior US Senate seat in 2010, W. Cleon Skousen’s son, Paul, told the New York Times that “Mike Lee is a good friend of the family, and we support him 100 percent. . . . He’s read Dad’s books; he had Dad in his home when he was growing up for visits and dinners, and he met Dad on a number of occasions before Dad passed away.”[106] Apart from the apparent influence of Skousen on Mike Lee during his childhood, Lee’s platforms align well with the religious and political vision for America espoused by Skousen during his career through much of the twentieth century. For example, both Skousen and Lee believe in the unconstitutionality of federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Federal Communications Commission, advocate for the repeal of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Amendments to the Constitution, call for the eradication of Social Security, decry the development of the American welfare state, and bemoan the national debt.[107]

Most importantly, Lee and Skousen both believe in a divinely inspired Constitution and are convinced of a diabolical attack by those who wish to suspend the freedoms it protects. In a February 2021 Conservative Political Action Conference speech at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Mike Lee identified local and federal government gathering restrictions due to the ongoing virus threat as evidence of the Left’s attack on freedom. Specifically, Lee believed that the assembly restrictions attacked American citizens’ ability to practice their faith, stating that “freedom of religion depends on it [the right to assemble]. . . . We’ve been prevented from gathering in our churches,” while also expressing his terror that the political Left’s “sole agenda is putting more faith in government. And as a result, they take steps inevitably to make us less free.”[108] He believed that the Obama administration and the subsequent Democratic coalition that sought to limit the influence of the Trump administration during his four-year term were part of the attack on the divinely inspired Constitution.

Early in his senatorial career, Mike Lee expressed his sentiments concerning the divinity of the founding document. In 2010, as a senatorial candidate, Lee appealed to his Utah Latter-day Saint base: “In my faith, the LDS faith, we do feel the Constitution has divine origins” and that the Constitution is something that “a religious person will regard as sacred.”[109] After winning the election, Lee repeated his campaign rhetoric that “this is a great land, and that governing document was written by wise men offered up by divine providence.”[110] Further, in 2015, Lee expressed that his view about a sacred Constitution is “consistent with the doctrinal view: I believe that the Constitution was written by wise men, raised up by God to that very purpose,” but he was careful not to suggest that it was equal with scripture. Rather, Lee asserted that the Constitution “is a special document that needs to be revered.”[111]

Thus, Mike Lee waving the NCCS pocket Constitution in the US Senate chamber on national television was not a mistake. It represented a material and distilled lens through which the Utah senator had built his congressional career and his religiopolitical worldview. Lee’s declaration that the Constitution “is a thing that works” when Americans read and understand the document goes hand in hand with the goals of the former FI and current NCCS. What is more is the annotated text of the pocket Constitution he “wasn’t aware” he was holding contains explicit Christian nationalist views on the divinity of the Constitution and the religious founding of the United States, views that Lee, and his political predecessors like Cleon Skousen, believed and taught.

Interestingly, other Latter-day Saint national politicians such as Orrin Hatch and Mitt Romney do not suggest these same beliefs. Both Hatch and Romney regularly have evoked their faith in public in connection to their political careers and both have acknowledged Skousen’s influence to some extent, Hatch more so than Romney.[112] However, it is reasonable to assume they are aware of the NCCS pocket Constitution’s association with right-wing extremism and sought to distance themselves from it in order to avoid being painted with an extremist brush similar to how Lee has been presented in the media as described previously. Thus, those who are aware of the NCCS pocket Constitution’s associations likely evoke it knowingly, to clearly capture its material presence and its implications: nationalism, libertarian-leaning politics, and radical Christian eschatology.

Conclusion

Arizona House Speaker Russell “Rusty” Bowers made national headlines because of his passionate testimony during the January 6th Committee hearing on Tuesday, June 23, 2022. Bowers refused to bend to pressure from the Trump administration in the wake of the 2020 election to recall the Arizona electors that Joe Biden had won. Many had done this over the course of the hearings, but Bower’s justification for refusing to comply was the reason for the increased attention. Bowers explained that “it is a tenet of my faith that the Constitution is divinely inspired,” and thus he would not give into demands to take actions that would cast doubt on the election’s outcome.[113] Bowers, a Latter-day Saint, evoked a distinct religious belief on the national stage that caught the attention of millions of Americans, including Chris Hayes who tweeted that “LDS theology helping to save the American Republic is a great twist!”[114]

The NCCS pocket Constitution posits the anachronistic juxtaposition of uncontextualized quotations from revered historical figures as evidence of a divine founding and intervention in the creation of the Constitution. The framing of the constitutional text with quotes that contend for a religious founding and advertisements for “expanding our knowledge” through NCCS published materials like The Making of America and The Five Thousand Year Leap represent an intentional curation on the part of the NCCS. The NCCS continues to put forward its associations with and influences by the likes of Skousen and Benson, which only further shows that this organization subscribes to the sentiments of these prominent ultraconservative voices from the twentieth century.

Most significantly, the pocket Constitution appears to have left its originating context with the NCCS and has found its way into the hands of popular public figures such as the Bundys and Mike Lee, along with millions of other Americans.[115] In appearing with these figures, and in such public venues, the NCCS pocket Constitution develops a corporeality, a material expression of religion. While journalists have pointed out the pocket Constitution’s radical Mormon origins, the presence and performance of the pocket Constitution have not been fully appreciated. Scholars of American religion should not discount these types of sources as kitsch, impartial, and insignificant. This study has demonstrated how unsuspecting pieces of material culture can and do find their way into the hands and minds of Americans and signify broader pervasive attitudes concerning the relationship of the American state and its founding documents to religion, Christian nationalist narratives, libertarian politics and free enterprise and the ability of “things” to package, encapsulate, and embody those ideas. The NCCS pocket Constitution does not simply express religion. In a material sense, it is religion.

[1] Jon McNaughton, “Pray for America,” Jon McNaughton Fine Art, accessed Nov. 10, 2021, https://jonmcnaughton.com/pray-for-america-11×14-litho-print/.

[2] Chris D’Angelo and Christopher Mathias, “We Need to Talk About Sen. Mike Lee’s Far-Right Pocket Constitution,” Huffington Post, Oct. 16, 2020, accessed May 31, 2021, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mike-lee-pocket-constitution_n_5f88b08cc5b681f7da1fdee3.

[3] Naomi LaChance, “Ultra-Right Annotated Edition of Pocket Constitution Tops Amazon Charts after Khizr Khan’s DNC Speech,” Intercept, Aug. 1, 2016, accessed Apr. 17, 2021, https://theintercept.com/2016/08/01/ultra-right-annotated-edition-of-pocket-constitution-tops-amazon-charts-after-khizr-khans-dnc-speech/.

[4] Birgit Meyer and others have explained that “a materialized study of religion begins with the assumption that things, their use, their valuation, and their appeal are not something added to a religion, but rather inextricable from it.” Birgit Meyer et al., “The Origin and Mission of Material Religion,” Religion 40 (2010): 210. Elsewhere, Meyer and Dick Houtman have argued that “religion cannot persist, let alone thrive, without the material things that serve to make it present—visible and tangible—in the world.” Dick Houtman and Birgit Meyer, “Preface,” in Things: Religion and the Question of Materiality, edited by Dick Houtman and Birgit Meyer (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), xv.

[5] “The Constitution,” Southern Utah News (Kanab, Utah), June 4, 1987, 2.

[6] “Freemen Institute Begins Second Year,” Utah Independent, July 14, 1972, 1.

[7] Alma 51:5–6.

[8] Dave Phillips, “‘Freemen Institute’ Presents Political Views, Literature,” Daily Herald, Nov. 29, 1971, 3.

[9] Jim Boardman, “Loved or Hated, Cleon Skousen Wields Big Political Stick,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 15, 1980, 2B.

[10] Matthew L. Harris, Watchman on the Tower: Ezra Taft Benson and the Making of the Mormon Right (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2020), 19.

[11] Boardman, “Loved or Hated,” 1B.

[12] 109 Cong., Rec. S114 (2006) (remarks of Sen. Hatch).

[13] J. J. Jackson, “Cleaver to Speak in Provo on Friday,” Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), Nov. 29, 1984, 22, https://www.newspapers.com/image/469370306/?terms=freemen%20institute%20name%20change&match=1.

[14] M. B. Brinkerhoff, J. C. Jacob, and M. M. Mackie, “Mormonism and the Moral Majority Make Strange Bedfellows? An Exploratory Critique,” Review of Religious Research 28 (March 1987): 245.

[15] Young, We Gather Together, 190.

[16] Young, We Gather Together, 192.

[17] Randal Powell, “‘The Day Soon Cometh’: Mormons, the Apocalypse, and the Shaping of a Nation,” PhD diss. (Washington State University, 2010), 257.

[18] Powell, “The Day Soon Cometh,” 257. Skousen was on an advisory board with the Christian Voice and joined the Council for National Policy, which both “united top New Right Christians, politicians, and donors to craft GOP agendas and policies.”

[19] Peter Gillians, “Freeman Institute Preaches Constitutionalism,” Daily Spectrum (St. George, Utah), Jun. 13, 1982, 18.

[20] Larry Eichel, “Cleon Skousen: Humble Teacher or Apostle of the Right,” Salt Lake Tribune, Aug. 2, 1981, 26.

[21] John Sillito, “Freeman Institute Changes Name,” Sunstone, Nov. 1985, 52–53. For more on The God Makers, see J. B. Haws, The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 112–125, and Young, We Gather Together, 192–201.

[22] “Final talks on Heritage Set Oct. 12” The Daily Herald, Sep. 21, 1979, 2.

[23] W. Cleon Skousen, The Secret to America’s Strength: The Role of Religion in the Founding Fathers’ Constitutional Formula (Salt Lake City: Freemen Institute, 1981), 1, 2, E. Jay Bell papers, 1833–2003, Box 23, Folder 1. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah.

[24] Michael Lloyd Chadwick, “The Task Facing America Today,” Freemen Digest, July 1978, 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

[25] “Prerequisites to Restoring the Constitution,” Freemen Digest, July 1978, 2, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

[26] “The Inspired Declaration of Independence” and “The Inspired Constitution of the United States of America,” Freemen Digest, July 1978, 43, 46, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

[27] Freemen Digest, July 1978, back cover, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

[28] “About the Painting,” Army Reserve Magazine 33, no. 3 (1987): 14.

[29] Mary Ann Marger, “Commemorative Painting Is Touring the Country,” Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Fla.), Oct. 10, 1987, 57.

[30] NCCS, The Constitution of the United States with Index, and The Declaration of Independence (Malta, Idaho: National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2009), back cover.

[31] NCCS, Constitution, cover, 1.

[32] NCCS, Constitution, iii.

[33] “From George Washington to Lafayette, 28 May 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-06-02-0264. Original source: W. W. Abbot, ed., The Papers of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1788 - 23 September 1788, Confederation Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 297–299.

[34] “Washington to Lafayette,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-06-02-0264. Original source: Abbot, Papers of George Washington, 6:297–299.

[35] For example, Sean Wilentz provides a deep account of the debates, controversies, and diversity of opinions regarding the Constitution’s democratic and antidemocratic elements, slavery, and the discussions surrounding the Bill of Rights. Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: From Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 13–39.

[36] NCCS, Constitution, iii.

[37] Daniel Webster, “Reception at Madison,” in The Works of Daniel Webster (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), 1:401–409.

[38] Brooks D. Simpson, “Daniel Webster and the Cult of the Constitution,” Journal of American Culture 15, no. 1 (1992): 15.

[39] W. Cleon Skousen, The 5,000 Year Leap: A Miracle That Changed the World (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Constitutional Studies, 1981): 98.

[40] Skousen, 5,000 Year Leap, 100.

[41] The closest and earliest usage of the phrase is in Francis Scott Key’s 1814 “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The poem’s fourth stanza reads “And this be our motto: ‘In God is Our Trust.’” While this phrase is not exactly what Skousen posits and what would much later become the United States’ official motto, it does resemble the current motto to some extent but still is outside of the periodization that most historians would consider the founding. See, Thomas Kidd, “The Origin of ‘In God We Trust,’” Anxious Bench, Nov. 10, 2015, accessed June 13, 2021, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/2015/11/the-origin-of-in-god-we-trust/; “History of ‘In God We Trust,’” Department of the Treasury, accessed June 13, 2021, https://www.treasury.gov/about/education/pages/in-god-we-trust.aspx.

[42] W. Cleon Skousen, “The Nature of Slavery,” in The Making of America: The Substance and Meaning of the Constitution (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Constitutional Studies, 1985), 729.

[43] “‘Glenn Beck’: Founders’ Fridays: George Washington,” Fox News, May 10, 2010, updated Jan. 14, 2015, accessed June 4, 2021, https://www.foxnews.com/story/glenn-beck-founders-fridays-george-washington.

[44] Steven K. Green, Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 11.

[45] Green, Inventing a Christian America, 12.

[46] “Revelation, 16–17 December 1833 [D&C 101],” 81, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed February 14, 2021, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-16-17-december-1833-dc-101/9.

[47] Jan Shipps, “The Prophet Puzzle: Suggestions Leading Toward a More Comprehensive Interpretation of Joseph Smith,” Journal of Mormon History 1, (1974): 16.

[48] Christopher Blythe explains that “Mormons understood this narrative in terms that cast the United States as a special land central to the tradition’s restoration project: the religious freedom available in the United States—limited as it might have been in practice—had made it possible for God to restore his church.” Blythe, Terrible Revolution: Latter-day Saints and the American Apocalypse (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 18.

[49] Haselby, Origins of American Religious Nationalism, 200. Haselby argues that “Protestant nationalists” were eager to “sacralize” the United States Constitution because of its “godlessness.” In any case, Haselby explains that Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Unitarians, and even Transcendentalists “thought patriotism a moral and religious duty. They believed that the United States of America had been chosen to play a sacred Christian role in history.”

[50] Sociologist Philip Gorski explains this idea well: “[Blood sacrifice] makes religious nationalism nationalistic: religion, people, land, and polity are all cemented together with dried blood in the form of blood sacrificed to God, blood flowing in veins, blood spilled in battle, blood showering down from heaven.” Phillip Gorski, American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2017). 21.

[51] During the Cold War, Church leader J. Reuben Clark wrote “that the price of liberty is and always has been blood, human blood, and if our liberties are lost, we shall never regain them except at the price of blood. They must not be lost!” J. Reuben Clark, Stand Fast by Our Constitution (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1965), 137.

[52] The most cited passage is found in Ether 2:12: “For behold, this is a land which is choice above all other lands; wherefore he that doth possess it shall serve God or shall be swept off; for it is the everlasting decree of God.”

[53] Perry and Whitehead consistently found that those who subscribe to Christian nationalism believe that the United States should have defined, secure, and regularly patrolled borders. They further found that support for Christian nationalism “naturally breeds xenophobia.” See Andrew L. Whitehead et al., Taking America Back for God (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), chapter 3.

[54] Philip L. Barlow, “Chosen Land, Chosen People: Religious and American Exceptionalism Among the Mormons,” in Mormonism and American Politics, edited by Randall Balmer and Jana Riess (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 109.

[55] “Discourse, circa 19 July 1840, as Reported by Martha Jane Knowlton Coray–B,” [13], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed Feb. 14, 2021, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/discourse-circa-19-july-1840-as-reported-by-martha-jane-knowlton-coray-b/5. For a more complete discussion of the “White Horse Prophecy,” see Don L. Penrod, “Edwin Rushton as the Source of the White Horse Prophecy,” Brigham Young University Studies 49, no. 3 (2010): 75–131.

[56] Christopher Blythe describes some of the key elements of the prophecy explaining that Joseph Smith predicted a future apocalyptic scene of the four horsemen of the apocalypse to “describe distinct American populations” and “an impending American revolution,” violence where “Father would be against Son & Son against the Father,” and foretold that the “White Horse [a symbol of the Mormon people] would send missionaries out to the Pale Horse (non-Mormon Euro-Americans) ‘to get the Honest among them . . . to Stand by the Constitution of the United States’ in the West.” For further in-depth discussion of this prophecy, see Blythe, Terrible Revolution, 139, 206–210.

[57] “Letter to Edward Partridge and the Church, circa 22 March 1839,” 8, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed June 3, 2021, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-edward-partridge-and-the-church-circa-22-march-1839/8.

[58] For example, in 1843, Willard Richards reported that Smith said that he was “the greatest advocate of the Constitution of the United States there is on the earth . . . the only fault I find with the Constitution, is, it is not broad enough to cover the whole ground. Although it provides that all men shall enjoy religious freedom, yet it does not provide the manner by which that freedom can be preserved, nor for the punishment of government officers who refuse to protect the people in their religious rights, or punish those mobs, states, or communities, who interfere with the rights of the people on account of their religion. Its sentiments are good, but it provides no means of enforcing them.” “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1 [1 July 1843–30 April 1844],” 1754, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed June 3, 2021, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-e-1-1-july-1843-30-april-1844/126.

[59] Historian Spencer W. McBride has shown that “it would take a civil war and the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868,” along with “several more decades for the federal government to consistently apply the free exercise of religion clause to individual states” to combat the afflictions that religious minorities, such as Catholics and Mormons, experienced in the antebellum United States. Spencer W. McBride, Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 214.

[60] Nathan L. Jones, “In the Nation of Promise: Mormon Political Thought in Modern America,” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 2019), 8.

[61] Benjamin E. Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier (New York: W.W. Norton, 2020), 199.

[62] Patrick Q. Mason, “God and the People: Theodemocracy in Nineteenth-Century Mormonism,” Journal of Church and State 53, no. 3 (2011): 358.

[63] Mason, “God and the People,” 371.

[64] David Walker explains that “theodemocracy critiqued also republicanism’s perceived shortcomings: excessive individualism, economic dislocation, the failure to acknowledge God as supreme lawgiver, and the continuing prevalence of state and mob violence constraining religious liberties.” David Walker, Railroading Religion: Mormons, Tourists, and the Corporate Spirit of the West (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 51.

[65] Mason, “God and the People,” 371.

[66] Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo, 201–204.

[67] On the question of whether the Constitution could be changed, Young affirmed that “it can” and that the framers of the Constitution “laid the foundation, and it was for after generations to rear the superstructure upon it. It is a progressive—a gradual work.” Brigham Young, “Celebration of the Fourth of July,” address given July 4, 1854, in Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: Amasa Lyman, 42 Islington, 1860): 7:14, https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/JournalOfDiscourses3/id/3130.

[68] For example, Christopher Blythe shows how Latter-day Saints saw the Civil War as divine judgment because of persecution endured by Latter-day Saints in Missouri, Illinois, and Utah, especially the recent “Utah War” of 1857. Blythe, Terrible Revolution, 130–178.

[69] John Taylor expressed this sentiment in the waning weeks of the American Civil War: “We expect to see a universal chaos of religious and political sentiment, and an uncertainty much more serious than anything that exists at the present time. We look forward to the time; and try to help it on, when God will assert his own right with regard to the government of the earth; when, as in religious matters so in political matters, he will enlighten the minds of those that bear rule, he will teach the kings wisdom and instruct the senators by the Spirit of eternal truth; when to him ‘every knee shall bow and every tongue confess that Jesus is the Christ.’” John Taylor, “Remarks Made in the Tabernacle,” reported by E. L. Sloan, Mar. 5, 1865, in Just and Holy Principles: Latter-day Saint Readings on America and the Constitution, edited by Ralph C. Hancock (Needham Heights, MA: Pearson Custom Publishing, 1998), 30.

[70] The elements of Alexander’s narrative that culminate in the “Americanization” of Mormonism consist of the following: abandonment of polygamy in favor of monogamy, theocracy in favor of the American republicanism (especially its two-party system), economic communalism in deference to pure American capitalism, and ecclesiastical evolution in the form of modern administrative bureaucracy, auxiliary organizations, and systematic formulations of doctrine, especially with the Word of Wisdom as a marker of good standing. What is unfortunately missing from this narrative are voices of “the laity” (what Blythe refers to via Primiano as “vernacular religion”), discussions of race (the Black priesthood and temple ban, relations with American Indians, Hawaiian immigration, etc.), and the complicated gender power dynamics inherent in the burgeoning administrative system. Thomas Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930, 3rd ed. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2012). Further, Kathleen Flake has shown how the prominent Reed Smoot Senate hearings in the opening decade of the twentieth century served as a major turning point in Latter-day Saints proving their Americanness as President Joseph F. Smith issued another manifesto prohibiting plural marriages and disciplined high-ranking Church officials for their failure to adhere to the original 1890 manifesto. The United States Senate and anti-Mormon interest groups in America had to give as well. The capitulation on the “Mormon problem” on the part of the United States came not only in the form of seating Senator Smoot but in curtailing its efforts to regulate the Church as a corporation in the ways the US Congress had been intervening in the economy for the preceding two decades through antitrust legislation. In the end, Flake succinctly posits that the “Mormon problem” that had plagued the United States for over half a century “was solved finally because the Mormons had figured out how to act more like an American church, a civil religion; the Senate, less like one” Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 158. Christopher Blythe has further demonstrated that this Americanization process included an expansion of the Church’s hierarchical role to moderate the Church’s theological, and in this case apocalyptic, tenets. Blythe argues that Church leaders were successful in their efforts to “Americanize” the apocalypse by regulating lay visions, revelations, and dreams that cast the United States in an antagonistic role and instead opted to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by supporting the Spanish-American War, disregarding the Ghost Dance, and officially disavowing the White Horse Prophecy. Blythe shows, like Flake, how the Church hierarchy forwarded reinterpretations in Church history and the prophecies of Joseph Smith to reorient the Church’s views toward the United States. Rather than vengefully calling upon God to smite the inhabitants of the United States for the murder of Joseph Smith, leaders emphasized their commitment to the Constitution due to its divine origins. Blythe, Terrible Revolution, 185, 213.

[71] After a public career as US under secretary of state (1928–1929) and ambassador to Mexico (1930–1933), Clark, trained at Columbia Law School, became a counselor in the Church’s First Presidency in 1933 during the Great Depression. Clark remained in the influential leadership position for the remainder of his life acting as the second counselor from 1933–1934 and 1951–1959 under Presidents Grant and McKay and as first counselor from 1934 to 1951 and 1959 to 1961 under Presidents Grant, Smith, and McKay. For more on J. Reuben Clark’s life and influence on the Church, see D. Michael Quinn, Elder Statesman: A Biography of J. Reuben Clark (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002); D. Michael Quinn, J. Reuben Clark: The Church Years (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1983); and Frank W. Fox, J. Reuben Clark: The Public Years (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1980).

[72] The plan was successful and revered by conservatives across the country, despite how lay Latter-day Saints in the “Mormon Corridor” (Utah, Idaho, Nevada, Arizona) voiced their political preferences by voting in overwhelming numbers for President Roosevelt and disproportionately received New Deal federal funds during the Great Depression. See Dave Hall, A Faded Legacy: Amy Brown Lyman and Mormon Women’s Activism, 1872–1959 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2015), 104–125.

[73] On November 16, 1938, Clark gave an address before the annual convention of the American Bankers Association in Houston, Texas, on “Constitutional Government: Our Birthright Threatened,” in which he stated, “It is not my belief nor is it the doctrine of my Church that the Constitution is a fully-grown document. On the contrary, we believe it must grow and develop to meet the changing needs of an advanced world.” J. Reuben Clark, “Constitutional Government—Our Birthright Threatened,” Nov. 16, 1938, in Hancock, Just and Holy Principles, 103.

[74] On June 14, 1954, Congress passed a joint resolution adding the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, and two years later, the phrase “In God We Trust” was adopted by the United States as its official motto and placed on American currency. Kevin Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 95–125.

[75] The remainder of Clark’s talk speaks to the liberal assault on the Constitution with the establishment of federal agencies and the expansion of the welfare state during the Great Depression. J. Reuben Clark, “Our Constitution—Divinely Inspired” (address at the General Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Apr. 6, 1957).

[76] Kruse, One Nation Under God.

[77] Bethany Moreton has demonstrated that “faith in God and faith in the market grew in tandem [through the postwar period], aided by a generous government and an organized, corporate-funded grassroots movement for Christian free enterprise. Bethany Moreton, To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 5.

[78] Matthew L. Harris, Watchman on the Tower: Ezra Taft Benson and the Making of the Mormon Right (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2020), 9.

[79] In the blessing, McKay blessed Benson to have the capacity and ability to fight communism, including that he “might see . . . the enemies who would thwart the freedoms of the individual as vouchsafed by the Constitution.” Quoted in Harris, Watchman on the Tower, 31–32.