Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

Membership Growth, Church Activity, and Missionary Recruitment

No other American religion is so ambitious, and no rival even remotely approaches the spiritual audacity that drives endlessly toward accomplishing a titanic design. The Mormons fully intend to convert the nation and the world; to go from some ten million souls to six billion. This is sublimely insane. … Yet the Mormons will not falter; they will take the entire twenty first century as their span, if need be, and surely it will be.

—Harold Bloom[1]

To comprehend the potential emergence of Mormonism as a major religious force in the twenty-first century, it is essential to comprehend the missionary ideology and practices of the LDS church. For rank-and-file Latter-day Saints, this proposition seems simply axiomatic of their foundational faith in the restoration of Christ’s gospel and their divine man date to convert the world in anticipation of his second advent.[2] For outside observers (and many LDS church planners as well), projecting and explaining the patterns of Mormon growth produced by evangelizing efforts in the world religious economy is complex and problematic.

By religious economy we mean the marketplace of competing faiths in a society where individuals exercise personal preferences in deciding about religious affiliation.[3] Where religious choice is possible and competition among different denominations for adherents is allowed by political authorities, we may speak of a religious market. As in other market economies, action in a religious economy is shaped by both supply and demand. Competing denominations must mobilize their resources in a simultaneous attempt to shape and cater to individuals’ religious preferences.[4] The structure of the world religious economy defines the historical context in which the LDS church is expanding through missionary recruitment. In this essay we examine LDS growth rates in different world regions as a function of the size and distribution of the LDS missionary force in comparison to other Christian missionary competitors. We focus in particular on the growth of new stake organizations as a measure of recruitment success and active lay retention. On the basis of these and other institutional indicators, we consider some of the prospects and potential problems for continued LDS missionary recruitment internationally in the century to come.

Religions grow over time through natural increase (i.e., birth rates that exceed both death rates and member defections), as well as through recruitment of new members. Natural increase has been an important source of Mormon growth historically.[5] Yet far more important to rapid expansion of the modern LDS church in many parts of the world has been a renewed emphasis on international proselyting since World War II and a willingness to concentrate church resources on the systematic enhancement of missionary programs. Missionary recruitment as the primary mechanism of LDS member growth in recent decades can be seen in Table 1. By 1960 the proportion of LDS membership growth worldwide due to annual conversions exceeded natural increase for the first time in this century and has continued to do so ever since. Currently, in fact, annual convert baptisms exceed those of Mormon children by approximately four to one. Clearly recruitment much more than natural increase is fueling current Mormon expansion.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1, see PDF below, p. 35]

Religious recruitment and conversion rates, however, vary dramatically from one world region to another. Relatively open, active religious markets are unequally distributed in the world religious economy. Old markets decline and new ones emerge. For example, as religious historians have long recognized, the population center of modern Christianity has shifted dramatically in this century from Europe and its colonies in North America to regions of the southern hemisphere. According to missiologist Andrew Walls, “The only safe prediction appears to be that [Christianity’s] southern populations in Africa, Latin America, Asia and the Pacific, which provide its present centers of significance, hold the key to its future.”[6]

As a rule, LDS proselyting success has followed general Christian trends; the overwhelming majority of Mormon converts are already Christians, who are recruited in markets already cultivated by other Christian denominations. Correspondingly, in recent decades LDS missions have proliferated in Christianized countries of the southern continents, especially in the predominantly Catholic countries of Latin America.[7]

Missionary Training

Dominant trends in Mormon proselyting programs since World War II, both in missionary preparation and in the field, include increasing reliance on: (1) uniformity of the proselyting message and how it is to be de livered by missionaries, (2) goal setting and outcome measurement by objective criteria, (3) standardized and programmatic training of missionary novices, (4) systematic supervision of missionary performance, and (5) cost-benefit accountability. These are all characteristics of the modern, bureaucratic ethos of corporate rationality and illustrate what Andrew Walls describes as the American business approach to Christian mis sions.[8]

According to LDS historian Gordon Irving, even though church leaders always urged lay members actively to support the missionary effort, “proselyting continued to be a relatively slow process during the 1950s. Missionaries would spend several months instructing converts prior to baptism, making sure that they fully understood every aspect of church doctrine and procedure before inviting them to become members. Mission presidents could see that help was needed for their elders, who, left to their own devices, hoped for spiritual guidance but often faltered in presenting the gospel convincingly to non-Mormons.”[9] A trend thus developed toward standard and systematic lesson outlines and aids in missions throughout the world.

In 1953 The Systematic Program for Teaching the Gospel became the first set of missionary lessons published by the church to be used in all missions. Prior to this time a number of ad hoc plans had been developed and used as aids in proselyting in different missions of the church with varying degrees of success. As noted by Jay E. Jensen, a former Missionary Department administrator and current member of the Second Quorum of the Seventy: “Having a systematic plan to present the message of the church gave rise to a systematic plan for training.”[10] In 1961 a conference for the world’s LDS mission presidents was convened by the First Presidency in Salt Lake City. As a result, missionary work “would never be the same, especially in mission field training.” At this conference a church wide program was unveiled for systematically involving the laity to implement the slogan “Every Member a Missionary,” and a new missionary plan was presented called A Uniform System for Teaching Investigators. Reflecting a rational, salesmanship approach, the Uniform System consisted of six missionary lessons which were to be memorized and used verbatim by all missionaries worldwide in teaching potential converts about the basic tenets of Mormonism. The key to increased proselyting success was presumed to be a standard message presented in a simple but systematic way. In addition, the daily activities of all missionaries were to be regulated henceforth by a standard schedule: “When to arise, when to study both as individuals and as companions, what to study, when and how to proselyte, and when to retire.”

Over the years the Missionary Department’s efforts to refine proselyting strategies and training procedures have centered on the goal of preparing individual missionaries to have “great converting power,” be yond their own native talents, in attracting new converts.[11] Later research sponsored by the Missionary Department on the teaching characteristics of missionaries who were most successful indicated that the way in which proselyting materials was presented to investigators, not just the standardized content of the missionary message itself, was correlated with increases in convert baptisms. Church researchers inferred that certain communication skills, transcending rote presentation of the investigator lessons, were important factors in the conversion process. They called these communication skills the “commitment pattern,” which they simplified for pedagogical purposes in the formula: prepare, invite, follow up, and resolve concerns.[12] In turn, each of these basic skill areas was analyzed in terms of a number of communication sub-skills. Thus emphasis in training eventually shifted from sheer memorization of lesson plans to training missionaries in the effective implementation of the commitment pattern.

Whether programmatic attempts to refine individual missionaries’ communications skills lead, on average, to significant increases in con versions has not yet been demonstrated (see, for example, the relatively stable, annual convert/missionary ratios shown in Table 1). Nonetheless, as a result of Missionary Department research findings, a second world mission presidents’ conference was convened in Salt Lake City in June 1985. At this conference yet a new set of missionary discussions was presented for implementation in all missions which, in its final form, was entitled Uniform System for Teaching the Gospel. This is the system currently taught to and used throughout the world by LDS missionaries. It is an approach that departs from the aggressive salesmanship of earlier plans in favor of a more “human relations” form of persuasion. Standard investigator lessons still are learned but need not be memorized word for word by missionaries, who are permitted to use their own phrasing in ex plaining religious precepts and are encouraged to “teach by the Spirit” in their testimonies and responses to investigator questions. This means that missionaries are given greater flexibility in presenting the content of their message while, at the same time, they are supposed to incorporate systematically the commitment pattern in all their discussions with investigators. Also introduced for universal use at the 1985 conference was a new training manual, The Missionary Guide, which adopted the commitment pattern as its basic training requirement. According to Jensen, “Missionary Department leaders have taken the position that all training materials must be built around the commitment pattern . .. The discussions and The Missionary Guide have been implemented in all MTCs [Missionary Training Centers] as the two principal tools to help missionaries learn and use the commitment pattern.”[13]

Later in this essay we will comment further on the socializing consequences of missionary preparation and field supervision, especially for missionaries called from outside the United States.

Church Growth and the Missionary Force

Independent of periodic attempts to refine missionary training and increase the persuasiveness of proselyting appeals in different religious markets, the overall number of converts to Mormonism appears most importantly to be a function of the sheer number of missionaries laboring in the field.[14] The single best predictor of the annual Mormon conversion rate is the size of the LDS missionary force. As indicated in Table 1, the average number of LDS convert baptisms per missionary usually ranges between five and seven annually worldwide. At the individual level, this would seem to be a tiny return on a tremendous investment of personal time and resources. At the aggregate level, however, an equally massive LDS missionary force producing at this rate accounts for a massive number of annual conversions (over 300,000 converts, for example, in both 1993 and 1994).

Following World War II, the size of the LDS missionary force rapidly surpassed pre-war levels, and so did the corresponding annual conversion rate. After a hiatus in missionary expansion caused by the Korean War, the number of full-time LDS missionaries tripled during the decade between 1954 and 1964, then continued to increase by over 50 percent per decade for the next thirty years. At the present time there are nearly 50,000 Mormon missionaries stationed in approximately 300 missions in Latin and North America, the South Pacific, Europe, parts of Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. As non-Mormon journalists Robert Gottlieb and Peter Wiley put it: “Almost overnight, this small Utah church became an international church, with an international missionary program beyond the dreams of any other church in the world.”[15] Today, in fact, there is no other single religious denomination in the world—Catholic, Protestant, or non-Christian—whose full-time proselyting force is remotely close in size to that currently recruited, trained, and supported every year by the LDS church.

Advancing hand in hand with the expansion of its missionary force and accelerated conversion rates after World War II has been the world wide proliferation of separate LDS mission field organizational units. In fact, one of the most visible structural trends in Mormon missions over the past fifty years has been the constant division and subdivision of mission field administrative units, resulting in an ever shorter geographical span of control and closer, more systematic supervision of missionaries.[16] The actual number of missionaries assigned to labor in particular missions varies from time to time and place to place, but the current norm is approximately 160 missionaries per mission unit. Yearly increases in the number of missionary volunteers requires the creation of new mission units within the boundaries of previously established missions and simultaneously stimulates expansion of mission field organizations into new religious markets for LDS proselyting. The number of Mormon missions increased from a total of twenty-nine worldwide in 1944 to 303 in 1994, for an average rate of increase per decade of 60 percent. During this time the proportion of international missions (i.e., those outside of North America) has gone from a little over half to 70 percent of all LDS missions (with Latin America currently accounting for one-third of the total). It was the past decade in particular which represented the greatest surge to date in new LDS mission field organizations, with a total increase of 82 percent since 1984.

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 1 and 2, see PDF below, pp. 40–41]

LDS expansion in the world religious economy can be compared to the evangelical efforts of other North American religious denominations. According to figures published in the Missions Advanced Research and Communications Center (MARK) Mission Handbook, there was an estimated combined total of 85,000 full-time Protestant missionaries world wide in 1992, many of whom were on furlough at any given time (an estimated 20 percent) or who functioned as staff in “enabling” (humanitarian) agencies rather than engaging in active proselyting. The single largest Protestant agency was the Southern Baptist Convention Foreign Mission Board, which supported 3,660 overseas career missionaries in 1992, and an additional 329 “short-termers,” who were serving two month to four-year assignments. We do not have data on the total number of proselyting Catholic missionaries worldwide but, according to MARK, U.S. Catholic missionaries (mostly religious order priests and nuns) serving abroad numbered 5,441 in 1992.[17]

A more detailed analysis of recent trends among North American Protestant mission agencies indicates an overall decline in the number of Protestant career missionaries serving in world markets. According to Robert Coote, assistant editor of the International Bulletin of Missionary Research, “The numerical growth rate of career missionaries over the last twenty-five years has failed to keep pace with the population growth rate in North America, let alone with growth rates in regions of the globe least exposed to the gospel.”[18] While it is principally mainline Protestant mission agencies in decline,[19] “nonecumenical” agencies (evangelical, pentecostal, and fundamentalists, which have come to represent over 90 percent of the North American Protestant missionary force) also experienced a 1988-92 leveling of their rates of growth.[20] While still ideologically committed to recruiting career missionaries, many Protestant agencies increasingly have turned to “short-termers” to fill growing gaps in missionary ranks. However, the increase of short-termers thus far has not compensated for early resignations and the declining rate of career enlistments. On an ending note of concern, if not alarm, for the future of Protestant evangelizing in the world religious economy Coote concludes that “we cannot rule out the possibility … that North American Protestant missions are facing a substantial decline, perhaps across all sectors.”[21]

By mainstream Protestant standards, all full-time LDS missionaries, including mission presidents, are short-termers. Compared to Christian career missionaries, the vast majority of Mormonism’s youthful missionary corps lack theological knowledge and ecclesiastical experience. Their relative immaturity, however, is balanced by idealistic enthusiasm and by a willingness to live spartan lives in a regimented proselyting program under experienced adult supervision. Most importantly, the full-time LDS missionary force continues to grow, with good reason to believe that its growth will extend well into the twenty-first century, while many Protestant mission agencies will struggle to maintain previous rates of recruitment in their missionary forces. Continued institutional emphasis on the lay missionary obligations of every member, and especially the intensive religious socialization of young males to accept full-time mission calls before assuming other adult responsibilities,[22] gives the LDS church a decisive missionary recruiting advantage over most evangelical competitors (who typically depend on idiosyncratic personal calls to the ministry in order to staff their missionary ranks).

Even if only a third of eligible young men accepts LDS missionary assignments, full-time missionary ranks should continue to expand along with the growing membership base.[23] If, for example, the size of the LDS missionary force were to continue to increase at a rate of 50 percent per decade for twenty more years, there would be 110,000 missionaries laboring in about 700 missions by the year 2015. Within fifty years at this same rate the church would be managing a force of over 370,000 missionaries in approximately 2,300 missions. As fantastic as these figures seem, they represent the current potential of Mormon proselyting efforts in the first half of the twenty-first century.[24] In turn, the single most important condition either facilitating or impeding the future growth rate of the LDS missionary force will be the rate of world increase in church members who are willing and able (1) to socialize their youth to accept missionary assignments and (2) to contribute financially to their mission field sup port. In any estimate of the Mormon future we must see the circular and reciprocal connection of member conversions, lay activity, and mission ary recruitment.

There are, of course, complicating factors, many of which (like political strife and wars) are completely beyond the church’s control. Further more, we cannot confidently claim to know what the limits are of Mormonism’s current appeal in existing religious markets—whether it is already very close to or far from having exhausted its appeal in such markets, especially in Christian countries. Even more ambiguous is what Mormonism’s potential appeal might be if new religious markets are opened in vast world regions, such as China, where Christianity has never had a strong footing. If it is to become a major world religion, we assume that Mormonism will continue having to make institutional accommodations and doctrinal adjustments to tailor its appeal in different world markets. Exactly what these adjustments might entail, or how effective they might ultimately prove to be, is difficult to say in advance. Furthermore, much of Mormonism’s current proselyting success is occur ring in regions where member resources are often precarious and inactivity rates have become a major source of concern for LDS officials. Since an active membership is essential to the institutional functioning of the church, and especially for the support of its lay missionary program, we need better indicators of Mormonism’s future than sheer membership growth projections.

Member Retention, New Stakes, and Church Growth

For some purposes, a superior way to measure Mormonism’s global development is to count the creation of LDS stakes rather than the total number of nominal members or convert baptisms. The organization of a stake presupposes a sufficient number of active members (particularly a sufficient number of active Melchizedek priesthood holders), in a relatively concentrated geographical area, who are both able and willing to staff the lay ecclesiastical organization required for the church’s full complement of priesthood and auxiliary programs at the local level. In addition, the organization of a stake also implies that an infrastructure of chapels, recreation centers, libraries, and associated equipment and sup plies can be established and maintained with church resources in a locally designated area. It is thus the creation and functioning of stakes, not just the initial professions of faith made by newly baptized members (who may or may not remain active) that corresponds most closely to LDS ambitions of building the kingdom of God on earth.

Based on information extracted from the 1995-96 Deseret News Church Almanac, we have tabulated the worldwide organization of LDS stakes by decade over the past half century. To facilitate generalizations we have aggregated the specific countries into six somewhat arbitrary world areas: North America (Canada and the U.S., excluding Hawaii); Latin America (Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean); the South Pacific (including Hawaii, Samoa, Tonga, Tahiti, Fiji, New Zealand, and Australia); Europe (including northern, central, and south ern Europe, Russia, and other republics and satellite countries of the former Soviet Union in Eastern Europe); Asia (Korea, Japan, and the Philippines); and sub-Saharan Africa.

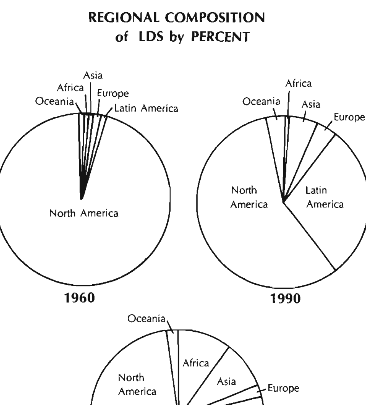

At the end of World War II there were 149 LDS stakes worldwide, 147 (99 percent) of which were in North America, with a concentration of 111 (75 percent) in the Mormon heartland states of Utah and Idaho. As of 1 October 1994 there were 1,998 LDS stakes worldwide, 801 (40 percent) of which were located in regions outside of North America. Though still representing a disproportionate concentration of stakes (502), after fifty years of Mormon expansion Utah and Idaho stakes have been cut to 25 percent of the world total. In the larger context of newly opening religious markets internationally and continued world growth for the church, the proportional reduction of North American stakes in general, and of Utah and Idaho stakes in particular, represent trends bound to continue well into the twenty-first century.

Shifting attention from half-century comparisons to decade comparisons, we get a better sense of variations in the rates of stake development in various parts of the world over time. Thus in North America from 1944 to 1984 we see an average increase of over 60 percent per decade in the formation of new stakes, a very strong record of sustained organizational growth and infrastructural development. Meanwhile, the rapid acceleration of stakes in Europe, Asia, the Pacific, and especially Latin America during the twenty-year period 1964-84 was even more dramatic. Beginning with a small organizational base of twenty-five stakes in 1964, growth in these four world areas increased by 444 stake units, or over 1,900 percent, in two decades. The surge of new stakes during this period was particularly strong between 1974 and 1984, a decade which coincided with the urgently growth-oriented administration of Spencer W. Kimball and produced 324 new stake organizations in those same world regions.

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 3 and 4, see PDF below, pp. 46–47]

In the past decade the actual number of LDS stakes organized in all world regions (including Africa as a relatively new market for active LDS proselyting) has continued to increase. However, the rate of stake formation from 1984-94 declined noticeably worldwide. For the first time since the mid-1950s, the growth rate per decade of new stakes dropped below 20 percent in Europe, the South Pacific, and North America. Though numerically still expanding, an overall decline in the rate of new stakes growth in Latin America and Asia also occurred during that decade.[25]

So even while LDS missions are proliferating around the globe, the missionary force becomes larger, and total LDS membership continues to grow steadily, the rate at which new stake units are organized has tapered off, at least for the time being. Since this slowdown has occurred only in the past decade, we cannot draw confident conclusions about the long-term implications for continued Mormon expansion. It might represent merely a brief, historical interlude for consolidating recent gains, to be followed by a new spurt of organizational growth in the next several decades. It might also signal the beginning of a much longer trend of declining stake growth in already established religious markets. In any event, the discrepancy in the past decade between growth rates in nominal church membership and the organization of new LDS stakes world wide indicates the need for a more complex analysis of the dynamics of international Mormonism in the twenty-first century.

Resources, Infrastructure, and Church Growth

Based on extensive interviews with ecclesiastical officials and church employees over a decade ago, Gottlieb and Wiley identified a looming “capital crunch” for the church brought about precisely by the dynamics of its own proselyting success outside of the United States. According to Gottlieb’s and Wiley’s sources, by the early 1980s financial managers within the church bureaucracy and some general authorities (especially Nathan E. Tanner) “began to question the continuing viability of the rapid expansion of the church, particularly in the Third World.” Newly formed congregations in rapidly expanding international areas typically could not meet their share of new chapel construction or maintenance costs or financially support other church programs, including missionary work. In order to expand internationally, the church had to squeeze its domestic base, resulting in a massive drain of funds from Salt Lake City. Alarmed by the depletion of financial reserves, church authorities began instituting cost-cutting policies: “Not only were the number of chapels and other church buildings cut back, but those built no longer were con structed in a way that reinforced the notion that Mormons were wealthy and powerful.”[26]

At the time Gottlieb and Wiley wrote their book on “the rise of Mormon power,” they anticipated a downturn in the annual growth of the LDS missionary force as an institutional response to the depletion of central church resources caused by high conversion rates in impoverished international areas. This has not happened. Instead, missionary enlistments and the development of new mission fields are continuing and, we think, will continue to do so well into the twenty-first century, if somewhat more slowly. However, as our data also indicate, there indeed has

been a decline recently in the rate of new stake organizations worldwide and concomitantly a decline in the rate of chapel construction and associated infrastructure investment. While we are not privy to the decisions and strategies formulated by church officials, we surmise that the current slowdown in new stake organization reflects a more prudent growth management policy, as described by Gottlieb and Wiley, calculated to keep church expenditures on infrastructure development in line with actual church income. Systematic implementation of a more conservative fiscal and managerial approach to the creation of new local congregations helps to explain the current discrepancy between the rates of nominal LDS membership growth and the formation of new stakes.

We seriously doubt, however, that Mormon officials are likely to deemphasize member missionary obligations any time soon as a mechanism for managing the rate of membership growth. The missionary ethos is too central to Mormon ecclesiology and to the dynamics of Mormon lay culture—too central, indeed, to Mormonism’s own history and future aspirations as a world religion in the next century—to be curtailed. This is true in precisely those international areas of greatest LDS growth, where the cultivation of a native missionary force plays a key role in the preparation of native ecclesiastical leaders. Ironically, it is the relative lack of male priesthood holders who are willing and/or able to assume lay leadership roles which often presents the most serious obstacle to the growth and development of LDS congregations internationally. We would interpret the slowdown in the rate of new stake organization in part as an acknowledgment of this problem at central headquarters, resulting in a greater institutional emphasis on cultivating an adequate leadership base before approving the investment of church monies into the creation of new stakes.

Here again we are forced to recognize the close interdependence of several core institutional factors in LDS growth and development. The cultivation of a viable native missionary force in international areas of Mormon expansion is contingent first on the formation of local stake and ward organizations under the direction of native leaders and subsequently on the institutionalization of Mormon youth programs, especially seminary and institute courses, which channel young people toward accepting missionary assignments when they come of age. Mexico provides one prominent example of this linkage. Native missionary enlistment rates in Mexico first began to climb in the 1960s and 1970s in conjunction with the rapid formation of native Mexican stakes and associated auxiliary programs beginning in the same period.[27] As of 1994, Mexico had 128 stakes[28] and was virtually self-sufficient in native missionaries, supplying at least 90 percent of the missionaries serving in eighteen different missions throughout the Mexican Republic.[29]

According to a former mission president and director of LDS schools in Mexico, the impact of church-sponsored education in Mexico has been critical there to Mormon growth. He credits the church education system with producing the current generation of native leaders who typically have followed a pattern of (1) enrollment in church schools and/or semi nary classes from which they (2) have gone on to accept and perform missionary assignments and (3) subsequently have returned home to assume ward and stake leadership callings.[30] Because of their youth and relative lack of ecclesiastical experience, returned Mexican missionaries often have faltered in leadership callings, but a large proportion also have succeeded. It is quite doubtful whether the extensive complex of LDS stakes and wards in Mexico today would be able to function were it not for the presence of thousands of local members who have passed through the missionary experience.[31]

Two other important infrastructural indicators of LDS development internationally are the creation of MTCs and construction of new temples, both in the United States and abroad. Like LDS stakes, MTCs and temples tend to follow active membership growth and support in given geographical areas, and both are linked to the promotion of native missionary activity. In addition to its twenty-six-acre flagship MTC in Provo, Utah, the LDS church in the last fifteen years has established MTCs in its major recruiting markets throughout the world, including Buenos Aires, Argentina; Sao Paulo, Brazil; Santiago, Chile; Bogota, Columbia; London, England; Guatemala City, Guatemala; Tokyo, Japan; Seoul, South Korea; Mexico City, Mexico; Temple View, New Zealand; Lima, Peru; Manila, Philippines; Apia, Samoa; and Nuku’ulofa, Tonga.[32] The Missionary Guide is the basic training manual used in all MTCs worldwide, and all missionaries, regardless of language or country of origin, learn and follow the standardized “commitment pattern” in their proselyting efforts.

MTCs have been established only in cities where temples are also located. Typically, in fact, the MTC is situated adjacent to a temple, where missionaries in training can be exposed to temple worship as an important part of their brief but concentrated preparation.[33] The Missionary Department’s long-term goal is to establish MTCs in every country where membership numbers and levels of church activity warrant the construction of a temple.[34] According to Charles Didier, current member of the presidency of the Quorums of the Seventy, “The best preparation is al ways in your own country. Not only does the church avoid the cost of transporting missionaries somewhere else for training, but also the local aspect is much more effective. We’d like to have one [an MTC] in every country.”[35] With a renewed emphasis on the importance of temple worship in LDS communities, we can look forward to a continued investment of church resources in the international construction of temples and a corresponding stimulus to native missionary activity and the creation of local MTCs.

Assuming that these particular international trends have become an integral part of the dynamics of modern Mormonism, we should not be surprised to see in the next century a steady increase in the number of non-North American missionaries to the point where they eventually surpass their North American counterparts as a proportion of the total missionary force. As always, however, this projection ultimately is con tingent on the willingness and ability of church members to bear the cost of a global missionary enterprise, which can be productive in the Mormon scheme of things only when it is matched by adequate infrastructural development. On top of tithes and fast offerings, members (especially in North America) also are encouraged to make regular contributions to the General Missionary Fund, which is used primarily to support the growing number of missionaries originating in Third World countries who otherwise could never hope to pay for their own missions.[36]

Cultural Constraints, Market Niche, and Church Growth

Mormon scholars have expressed some concerns in recent years about institutional problems which might complicate the church’s efforts to become a world religion. For example, in his analysis of the dialectical tensions between LDS accommodation and retrenchment within Ameri can society, Armand Mauss concludes that, both doctrinally and socially, modern Mormonism is listing in the direction of Protestant fundamental ism and is in peril of losing its peculiar Latter-day Saint identity in the religious economy.[37] Mauss worries that current Mormon retrenchment trends in scriptural literalism, corporate church governance, traditional gender role definitions, youth indoctrination, and political conservatism threaten to limit Mormonism’s potentially universal appeal primarily to individuals already inclined toward a fundamentalist, authoritarian out look. Consequently he suspects that such individuals are being disproportionately recruited by the missionary enterprise and actively retained in the modern church. In part this analysis reflects the growing alienation of liberal Mormon intellectuals themselves (always a small fraction of the Mormon lay community) from the institutional church. Yet to the extent that it is also true, it might predict a selective market niche in the religious economy and a definite ceiling to the prospects of continued Mormon expansion. It is the potential size of that niche, however, that is a key question to be answered. In the United States, at least, LDS retrenchment has been in harmony with resurgent conservatism in national life since the late 1960s, and this, no doubt, has contributed significantly to Mor monism’s enhanced market appeal in the U.S. religious economy. There is no compelling indication at the moment that the popular ideological ap peals of religious conservatism—or even authoritarianism—are about to wane on the American religious scene.

In spite of its rapid international growth, outside the United States the LDS church is still, as Larry Young reminds us, a very small minority religion in almost every part of the world and continues to experience considerable strain and conflict in many of the host societies where it is attempting to take root.[38] In Young’s view, the major problem internationally for the modern church is not so much its literalistic theology but its top-down administrative structure, which tends to suffocate local initiatives attempting to respond to local problems. Young sees current Mormon retrenchment trends described by Mauss primarily as an assertion of the church’s fundamentally theocratic form of organizational hierarchy (which, of course, always has been an ambiguous source of both unity and division in Mormon history). He argues that Mormon bureaucracy has become well accommodated to the corporate structure of North American society but is out of joint with social realities in other parts of the world and often is inflexible in adjusting to local circumstances in foreign cultures, where many converts are lacking in formal education. Young points to major retention problems for the church in many international areas where new converts are often unwilling or unable to function as active participants in centrally coordinated lay programs. Like Mauss, he speculates that the church’s modern appeal is limited mostly to selected segments of the international religious market; that it is most likely to retain the active participation of middle-class professionals, who can be assimilated more easily into an Americanized organizational culture that stresses record keeping, reporting and supervisory systems, hierarchically-imposed objectives, and standardized programs. This is particularly true for the recruitment of native leaders into the administrative ranks of general authorities, mission presidents, stake presidencies, bishoprics, church education and welfare services personnel, etc. Rank-and file converts must, of course, also learn to comply with the requirements and structures of local priesthood and auxiliary programs. Finally, it is the distinctly American character of Mormon organization and ecclesiastical practice that, according to Young, has created image problems and conflicts for Mormonism in nationalistic Third World countries, where negative associations are often made linking the church with Yankee imperialism.[39]

Both Mauss and Young appear to believe that if Mormonism is to realize its potential as a major world religion in the next century, it will have to decentralize its decision-making procedures, become less bureaucratic in local governance, less parochial in its lifestyle prescriptions, and more tolerant of cultural heterodoxy. Whether these are desirable adjustments is not the question here. The question is whether they are necessary for Mormonism to continue global expansion and for how long at its current rate. While we find much with which to sympathize in both Mauss’s and Young’s analyses, we think that at least for the foreseeable future insistence on doctrinal orthodoxy and the centralized, corporate managerial approach (which has worked well thus far in mobilizing church resources and member support for missionary expansion) will continue to be the Mormon norm worldwide. We have no reason to believe that current Mormon authorities or their immediate successors will soon abandon an apparently successful formula for unprecedented institutional growth, in spite of the accompanying economic strains and cultural conflicts. The institution of area presidencies a decade ago, which placed general authorities in closer touch with local conditions and expedited decision-making and the allocation of local resources, was not designed to produce a more pluralistic church with federated power centers, nor has it done so. The periodic rotation of members of the Quo rums of the Seventy in area presidencies, and their closely monitored performances at central headquarters, works against the gradual emergence of autonomous regional churches. If anything, the institution of area presidencies has brought church operations in faraway places, including mission fields, under closer scrutiny and administrative control than ever before.[40]

We find many of the insights offered by Gottlieb and Wiley concerning modern Mormonism’s internal strains to be as valid now as they were a decade ago:

Today, the church faces a contradiction between its bottom-line considerations and its fundamental purpose—to expand the church. For the future, these contradictions might well intensify as the church’s desire to become more like a corporation clashes with its desire, as a correlated and missionary-oriented church, to spread its message and bring in new members throughout the world as rapidly as it has over the last thirty years…. The financial situation has, to a certain extent, forced the issue of what kind of Mormon church will emerge throughout the next two decades of this century. One route, which Mormon liberals hope will be followed, involves the development of any kind of diversity and cultural pluralism. The likely route, however, involves a further strengthening of the hybrid Mormon American culture based on a narrow and centrally defined reading of doc trine, with all decisions still flowing from Salt Lake.[41]

What Gottlieb and Wiley call the “hybrid Mormon-American culture” corresponds to Young’s depiction of a middle-class managerial church. It is a church whose missionary message can be somewhat tailored to different segments of the religious economy in order to maximize the appeal of its doctrines and values. Yet the church’s emphasis on active lay participation seems less susceptible to market modification. Lay participation in the modern church, especially in leadership positions, presupposes a certain literacy level, as well as a willingness to function in a bureaucratically regulated organization. Many LDS converts, attracted by different aspects of Mormonism’s religious promise, are not disposed to assume organizational roles. Those converts who do become active organizational members represent a narrower band of the religious market than those who initially join the church through baptism. This, of course, is true in varying degrees for virtually every established religious denomination. The basic institutional problem for all evangelical movements is to retain a sufficiently large core of active participants to allow for continued expansion.[42]

In Mormonism the dual functions of expansion through recruitment and retention of members through church programs are both served by the missionary system. The church, especially in the high growth regions of Third World countries, has come to depend on local missions as socializing agencies for native missionaries. In many respects the mission field organization is both an idealization and a microcosm of the institutional church. In the field young Mormon missionaries are immersed in a managerial ethos of daily planning, reporting, and supervision. They are grounded in institutional procedures. They are being groomed to assume local leadership positions on completion of their full-time proselyting service. It is in the mission field where the hybrid Mormon-American culture is most clearly modeled and transmitted. Retaining the participation of a sufficient fraction of returned native missionaries, socialized and equipped to discharge organizational roles, is of key importance to the continued international development of Mormonism in the twenty-first century.[43]

This is the formula which, all things considered, has worked very well since the end of World War II and, in our analytical peep-stone, will continue to be followed in the century to come. This is in spite of the potential of market saturation in the religious economy, convert member defections and inactivity rates, alienation of intellectuals, and even nationalistic schisms. The transfer of church resources to developing areas of the international church undoubtedly will continue, but more selectively and under even greater institutional scrutiny than in the past. The rate of Mormon expansion eventually will slow down in the next half century, especially the infrastructural organization of new stakes, but not before the LDS church has become a major presence in the world religious economy.

[1] Harold Bloom, The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 113.

[2] For a recent historical analysis of LDS millenarian beliefs and their relationship to the development of the Mormon missionary ethos, see Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

[3] For applications of the concept of religious economies, see Roger Finke and Rodney Stark, The Churching of America: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992); Laurence R. Iannaccone, “Religious Markets and the Eco nomics of Religion,” Social Compass 39 (1992): 123-31; Darren E. Sherkat and John Wilson, “Preferences, Constraints, and Choices in Religious Markets: An Examination of Religious Switching and Apostasy,” Social Forces 73 (Mar. 1995): 993-1026; Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge, The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival, and Cult Formation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

[4] See Peter L. Berger, The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (New York: Doubleday, 1967), 138-53; and Darren E. Sherkat, “Embedding Religious Choices: Integrating Preferences and Social Constraints into Rational Choice Theories of Religious Behavior,” in Lawrence Young, ed., Assessing Rational Choice Theories of Religion (New York: Routledge Press, 1995).

[5] Tim B. Heaton, “Vital Statistics,” in Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4:1522,1524.

[6] Andrew Walls, “Christianity,” in John R. Hinnells, ed., Handbook of Living Religions (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Viking, 1984), 70, 73.

[7] See Heaton, 1521.

[8] Andrew Walls, “World Christianity: The Missionary Movement and the Ugly American,” in Wade Clark Roof, ed., World Order and Religion (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1991), 156- 58.

[9] Gordon Irving, “Mormonism and Latin America: A Preliminary Historical Survey,” Task Papers in LDS History, No. 10 (Salt Lake City: Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1976), 22-23.

[10] All the information in this paragraph comes from Jay E. Jensen, “The Effect of Initial Mission Field Training on Missionary Proselyting Skills,” Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1988, 29,31,32-33.

[11] Ibid., 4.

[12] Missionary Guide: Training for Missionaries (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1988), 44-71.

[13] Jensen, 43. After several “test versions,” the final version of The Missionary Guide was finally adopted in 1988.

[14] While many programs have been developed to increase missionary productivity, “since 1970, the only factor that seems to have accounted for an increase in convert baptisms was an increase in the number of full-time missionaries … Even though the number of con verts has increased only as the number of missionaries has grown, Missionary Department executives have operated on the assumption that missionary training can make a difference to increase converts” (ibid., 1). For other summaries of the development of LDS missionary training and proselyting approaches since World War II, see Richard O. Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel in His Own Language (Provo, UT: Missionary Training Center, 1984); and George T. Taylor, “Effects of Coaching on the Development of Proselyting Skills Used by the Missionary Training Center, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Provo, Utah,” Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1986.

[15] Robert Gottlieb and Peter Wiley, America’s Saints: The Rise of Mormon Power (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), 14.

[16] See Gordon Irving, Survey of LDS Missionary Work, 1830-1973 (Salt Lake City: His torical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1974), 16-23.

[17] John A. Siewert and John A. Kenyon, Mission Handbook: A Guide to USA/Canada Christian Ministries Overseas, 1993-1994 (Monrovia, CA: MARK, 1993).

[18] Robert T. Coote, “Good News, Bad News: North American Protestant Overseas Personnel Statistics in Twenty-Five-Year Perspective,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 19 Qan. 1995): 6.

[19] Michael Burdick and Phillip Hammond, “World Order and Mainline Religions: The Case of Protestant Foreign Missions,” in Roof, 202.

[20] Coote, 11.

[21] Ibid., 11.

[22] Lack of official encouragement notwithstanding, single women have served full time LDS missions since the turn of the twentieth century. See Vella Neil Evans, “Woman’s Image in Authoritative Mormon Discourse: A Rhetorical Analysis,” Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1985, and Calvin S. Kunz, “A History of Female Missionary Activity in the Church, 1830-1898,” MA. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1976. Until the last two decades, sister missionaries represented only a small fraction of full-time Mormon missionaries in the field; but, according to a personal communication from the Missionary Department, in recent years the proportion of young women has increased significantly to about 20 percent of the total LDS missionary force. Today there are more LDS young women pursuing college educations and vocational training, while also volunteering in larger numbers for missionary assignments, than ever before. In part this is a reflection of larger national trends among women. It indicates a growing number of women in the church who are willing to postpone marital and family aspirations until later in their lives than customarily has been the Mormon norm.

[23] About one-third of those eligible has been the norm in recent years. See Darwin L. Thomas, Joseph A. Olsen, and Stan E. Weed, “Missionary Service of LDS Young Men: A Longitudinal Analysis,” unpublished paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, 1989,17.

[24] A declining birth rate among the core North American membership could begin to have a substantial impact on LDS missionary force enlistments. To the extent that this occurs, a relative decline in the number of young men eligible for missionary assignments in U.S. and Canadian congregations would have to be off-set by a corresponding increase in the percentage of non-North Americans and young women in order for the size of the missionary force to continue expanding at its current rate. If church authorities ever changed the required age for single sister missionaries from twenty-one to a lesser age, and /or encouraged young women to prepare for full-time missionary assignments with the same emphasis given to the socialization of young men, missionary enlistments would increase dramatically.

[25] Our tabulations from the 1995-1996 Church Almanac showed that it was principally the Philippines that boosted the rate of stake development in Asia during the last decade, with the organization of forty new stakes (84 percent of the Asian total from 1985-94). The rate of new stake development in other Asian countries, particularly Japan and Korea, dropped significantly in this same period.

[26] Gottlieb and Wiley, 124,155-56.

[27] See Irving, “Mormonism and Latin America”; Agricol Lozano Herrera, Historia del Mormonismo en Mexico (Mexico, D.F.: Editorial Zarahemla, S.A., 1983); and F. Lamond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987).

[28] 1995-96 Deseret News Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1994), 258.

[29] Elayne Wells, “Centers Prepare Missionaries to be Effective Instruments,” Church News, 13 Jan. 1990, 6.

[30] Earin Call, personal communication, Jan. 1994.

[31] For a discussion of the interrelated topics of church education, missionary recruitment, and native ecclesiastical leadership in Mexico and Latin America, see F. Lamond Tullis, “Church Development Issues Among Latin Americans”; Harold Brown, “Gospel Culture and Leadership Development in Latin America”; and Efrain Villalobos Vasquez, “Church Schools in Mexico”; all in F. Lamond Tullis et al., eds., Mormonism: A Faith for All Cultures (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1978).

[32] Gerry Avant, “Missionary Training Center Expands,” Church News, 19 Mar. 1994,11.

[33] Richard O. Cowan, “Missionary Training Centers,” in Ludlow, 914.

[34] At the present time there are sixty temples in use, planned, or under construction worldwide, with twenty-nine in North America, eleven in Latin America, seven in Europe, six in the Pacific, five in Asia, and one in Africa. See the 1995-96 Deseret News Church Almanac, 329-30.

[35] Wells, 6.

[36] Currently, about one-quarter of the full-time LDS missionary force is made up of missionaries called from outside the U.S. and Canada. World areas where the greatest numbers of local missionaries are serving are Latin America, the Philippines, and the South Pacific—precisely those areas where proselyting success and development of new stakes have been greatest internationally. At the same time, a majority of these missionaries are financed through the church’s General Missionary Fund. See John L. Hart, “Local Missionaries Supported in Service by International Fund,” Church News, 13 Nov. 1993,3.

[37] Armand L. Mauss, The Angel and the Beehive: The Mormon Struggle with Assimilation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

[38] Lawrence A. Young, “Confronting Turbulent Environments: Issues in the Organizational Growth and Globalization of Mormonism,” in Cornwall et al., 43-63.

[39] Problems of cultural dissonance for the LDS church are shared with other evangelizing North American denominations, particularly in Catholic Latin America. See Graham Howes, “God Damn Yanquis: American Hegemony and Contemporary Latin America,” in Roof, 91.

[40] According to instructions and operating procedures given in the 1990 Mission Pres ident’s Handbook (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), mission field organizations are monitored and supervised conjointly by Area Presidencies and the Missionary Department in Salt Lake City. Thus “mission presidents report to and receive di rection and training from Area Presidencies. Unless noted otherwise, dealings with head quarters are handled through the Area Presidency” (2). At the same time, “the Missionary Department… assigns a representative to help them [the mission president and his wife] prepare and to work with them throughout their mission. In matters affecting the status of individual missionaries (surgical operations, health, conduct problems, etc.), the mission president should contact the Missionary Department. The Area Presidency should also be apprised of more serious cases” (ibid.).

[41] Gottlieb and Wiley, 128,156.

[42] Robert E. Wells, current member of the First Quorum of the Seventy and a former Mexican mission president, reported several years ago that in Mexico “we normally get one third of our people out to stake conference. We get about one-third of our people attending sacrament meeting. We have a challenge. One-third of our people are fully active always. One-third are lukewarm and one-third we don’t see back in church a few weeks after they’re baptized.” Undaunted by member retention problems connected with rapid LDS growth in Mexico, Wells went on to say,

We’ll just call the best men and let the Lord bless them and magnify them … It doesn’t bother me to see imperfect leaders … We’re plowing ahead without perfect leaders… I would rather see a mission baptize 1,000 a month and lose 333, but have 777 there, than baptize 10—like some European missions, who also lose 3 to total inactivity … The Savior said the kingdom is like fishermen who cast the net and bring in all kinds of species, and that’s what we’re doing—we’re bringing in everybody that will promise to live the commandments, knowing full well that probably a third of them won’t. But that doesn’t bother me at all (from an untitled talk given to a BYU alumni group at the Benemerito School, Mexico City, Jan. 1988, copy in our possession).

[43] Some older studies estimated the inactivity (or dropout) rate of returned Mormon missionaries in the U.S. to be about 10 percent (see John M. Madsen, “Church Activity of LDS Returned Missionaries,” Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1977). More recent figures have not been published, and to our knowledge the subsequent inactivity rates of returned Mormon missionaries from outside the U.S. have not been studied. Our hunch is that non U.S. missionaries are more likely, on average, to withdraw from active lay participation once they complete their missionary service and return home than are their North American coun terparts, but we have no empirical evidence to support this.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue