Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 1

Minerva’s Calling

Minerva Bernetta Kohlhepp Teichert may be the most widely reproduced and least-known woman artist in the LDS Church. Her paintings have appeared more than fifty times in Church publications since the mid-1970s. Her Queen Esther appeared on the cover of the 1986 Relief Society Manual. No fewer than eleven of her works appeared in the September 1981 Ensign, a special issue on the Book of Mormon. Minerva painted almost five hundred paintings that we know of during her life. Furthermore, she created these in a virtual vacuum, working on an isolated ranch in Cokeville, Wyoming, for nearly forty-five years with no associates who understood her effort to translate Mormon values into art, no professional art community to reinforce her efforts or pose as a critical foil for her work, and no warmly appreciative audience of admiring patrons. She had to rely on her own sure sense of self to give her the impetus necessary for her energetic, imaginative, and prolific output.

As one becomes familiar with the total span of her art, it is apparent she was far more than a simple illustrator of gospel stories and LDS Church his tory. Instead, she was a skilled and sophisticated painter, unusual for her period and unique in her milieu. The first major exhibition of Teichert’s work, scheduled for 18 March-10 October 1988 in Salt Lake City at the LDS Museum of Church History and Art, is an opportunity to experience the vitality of her too often misunderstood and underrated works.

Minerva’s Life Sketch

Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert was named for her grandmother, Minerva Wade Hickman, a midwife, in whose North Ogden home she was born on 28 August 1888.[1] She was the second of Frederick John Kohlhepp and Mary Ellen Hickman Kohlhepp’s eight children. In 1891 the family moved to a homestead in Indian Warm Springs, Idaho, a mineral spring about five miles from American Falls in the Snake River Valley. Minerva’s father, reared in a comfortable Boston home before heading west, began her education by reading aloud from the Bible, particularly the Old Testament; but her mother began her artistic education by giving her a set of watercolors when she was four. From that moment, Minerva later recalled, she considered herself an artist, always carrying a sketchpad and charcoal or pencil in her pocket (Kissane 1982, 2).

In 1900 she lived with her grandmother Hickman while she completed the eighth grade. The next year she lived with family friends in Blackfoot, Idaho, since her father’s store had burned down. In 1902, she visited San Francisco and Los Angeles with an Idaho family as the fourteen-year-old nanny for their children. While in San Francisco she attended the Mark Hop kins Art School. Later in Pocatello she boarded with a Mrs. West, an artist who admired Minerva’s drawings of Gibson girls, popular contemporary illustrations of elegant beauties in the style of Charles Dana Gibson. Minerva painted these illustrations on silk for pillows, but even then she knew that life held more for her.

From 1902 to 1903 she attended high school in Pocatello, then taught school at Landing and Rockland, both in Idaho, helping to support her father who had been called to an LDS Swiss-German Mission. In about 1905, she asked Salt Lake photographer C. R. Savage and John Held, Jr., (then a Utah artist who later became the foremost American cartoonist of the 1920s) about how to further her artistic education: Held advised her to go to the Art Institute of Chicago. But the idea of a young girl heading eastward would take several years for her family to accept, and in the meantime she needed to teach and save enough money for the trip.

During the summer of 1907 Minerva and her siblings pitched hay in the harvest, and by that fall she had earned enough to attend a local teachers’ academy for a few months. Then she taught at Davisville, Idaho (near Soda Spring), and from late 1908 to early 1909 in Yale, Idaho. Then in April she went to Chicago for the first time, after having been “set apart” by her father (for protection) and sent to live in the LDS mission home there. Minerva was thrilled with professional art training—the Art Institute of Chicago was one of three or four outstanding art schools in the nation. Much of her time out side of the institute was spent with Church members attending concerts and cultural events. It was in Chicago that Minerva gained a lifelong interest in music and theater, which later led to frequent involvement in ward and school theater productions and learning to play the piano.

Chicago proved to be expensive for a young girl with meager financial resources, and Minerva was forced to return to Idaho by the end of the summer. But she had now experienced the national art community, and she vowed to return, which she did the next year after doing local teaching once again. Minerva’s influential teachers included Fred De Forest Schook, Antonin Sterba, and especially John Vanderpoel, a member of the institute faculty for thirty years.[2] Vanderpoel was known for his murals and textbooks; The Human Figure particularly influenced her drawing style. Minerva considered him “the greatest draftsman America has ever had.” Crippled by an accident at fourteen, he was, as Minerva described him, “that little hunch-backed man who we felt was so big and high that he walked with God” (M. Teichert to Birch, n.d.).

In August 1910, Minerva returned home to complete a four-week Idaho State Normal Teaching Course and later spent time “proving up” an Idaho homestead for her family during the next fourteen months, which involved building a dwelling, establishing residence, and making improvements. A dauntless and courageous young woman, she stayed alone, sleeping with a gun under her pillow. In 1910 she taught school at Swan Lake, Idaho, earning enough to go back to Chicago for some more classes at the institute in 1912. During 1913-14 she returned to teach in Sterling, Idaho, where she became better acquainted with a local cowboy, Herman Adolph Teichert, not a member of the LDS Church, whom she would later marry.

After school was over in 1914, she painted china in Salt Lake City and then went to American Falls, where she worked for a newspaper. One more year of teaching, this time in Pleasant View, Utah, provided her with enough funds to launch her on her most exciting journey. For thirteen months, from April 1915 to May 1916, she studied at the Art Students’ League in New York City. This was an exciting time to be in the nation’s cultural capital, since New York was filled with expatriates, especially artists, from a wartorn Europe.

Her most influential teacher at this time was George Bridgman, author of three major books on anatomy, figure drawing, and features.[3] He immediately recognized Vanderpoel’s influence upon seeing Minerva’s drawings and enthusiastically served as one of her mentors in New York. A dozen of Minerva’s wonderful life drawings survive from her student days, and we can see both the strong imprint of Bridgman, who added his sketches and corrections in the margins, and the strong artistic personality of Minerva Kohlhepp, whose interpretive view transformed these academic exercises into art. This is particularly true in An Indian Youth and Female Nude.

The league refused patrons because, as Minerva later explained in her short autobiography, “The artists are afraid of them gaining influence, so they just go along on their own. One thing wealthy people can do is give their theater and opera tickets. Since I was one of the most advanced students, I had many. Paderewski was playing his best, and Caruso was singing his grandest” (cl937, 11). She regularly visited New York’s many museums; her favorite was the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she copied paintings by Velasquez and Rembrandt. She particularly admired Rembrandt’s ability to create an inherent spiritual quality in his subjects by his subtle use of lighting. She loved music and somehow found time to study the piano.

She also supplemented her income by appearing in vaudeville as a skilled trick roper and Indian dancer and gave dramatic readings. She also resource fully looked ahead to the Christmas rush and in July began “making wild and domestic animals, birds, funny things, etc. By Xmas they expect to have lots for me and all my Santas will come in handy” (M. Teichert to “Folks,” 1915). She also painted several portraits on commission and “made a sketch of Wallace Beery for a movie he was acting in and received fifty dollars” (M. Teichert c 1937, 14).

She had begun sketching animals when she was quite young and as a result had become quite proficient. According to her autobiography, “When anyone came to the league seeking an animal painter, the job was given to me” (cl937, 14). Her future patron, Dr. Minnie P. Howard, wrote in the Idaho Daily Statesman about 1917 that a New York critic had earlier observed that Minerva was doing “the most vigorous animal work being done at this time by a woman painter in the United States.”

A perceptive and prolific letter writer, Minerva sent home entertaining and insightful letters comparing the children on New York streets with those of her hometown, discussing modish styles of dress, and fantasizing about buying new hats and dresses. Although Minerva, like so many other adopted New Yorkers, had learned the elements of good taste and high fashion, her own situation dictated a modest wardrobe. “When my clothes are kind of shabby,” she wrote home to the “Folks” in 1915, “I feel a little more humble and work better. The artists say, ‘The bigger your dinner the more you loaf.’ ” Later she described her experience of going home to Idaho in her old clothes and how the neighbors hardly noticed she was back. She couldn’t help feeling dis appointed, and from her point of view it was because of her old clothes that the neighbors undoubtedly believed New York had not really changed her after all.

George Bridgman recommended her for a scholarship at the league which enabled her to continue her studies as an advanced student with the great artist and teacher Robert Henri. He was the leader of a well-known group of urban realists called “The Eight,” who as mavericks had exhibited independently in 1908 to protest “the devitalized standards of the National Academy” (Henri 1910, 160). Close to the end of her New York experience, Minerva was also awarded a scholarship to continue her studies in London, but this proved difficult to accept for her mother, whose daughter was already far away from home.

Although Minerva acknowledged Vanderpoel, Bridgman, and Henri as her mentors, she became closest to Henri. How much influence he had on her is suggested by his observation upon critiquing an art show in New York: “As I see it, there is only one reason for the development of art in America, and that is that the people of America learn the means of expressing themselves in their own time and in their own land” (1910, 164). His ardent nationalism became a working credo for Minerva, and he became her prime master. Al though many of her student works that survive are carefully drawn and aca demic in nature, even then her mature style is apparent. In these early works we see a tendency toward simplification and a modeling of surface planes. Minerva’s mature style reflected Henri’s admonition to “stop when the story was told.” Her quick and dynamic brush strokes were certainly influenced by his point of view. Several of Minerva’s portraits are similar in spirit and technique to certain works of Henri. They indicate heavier color application and the spontaneous expression typical of Henri (1951, 20).

One of his maxims became her byword throughout her artistic career: “When the story is told, the picture is finished” (Oman and Oman 1976, 58). Many of Minerva’s paintings would show this characteristic; she left back grounds vague, painting in figures but leaving their feet and legs sketchy and unfinished. Because most of her larger pieces, like the work of the Byzantine mosaic muralists, were designed to be viewed from a distance, she seldom gave them a polished attention to detail. She strove to keep intact the verve and freshness of the original drawing and line.

When she was struggling with a decision to go back or try to find some way of staying in the East, Henri told her “to go home and paint the great Mor mon story.” This injunction was a precise reflection of his philosophy, and it was the mandate Minerva quoted frequently, even in LDS sacrament meetings. It must have been a great support to her in times of discouragement. Henri, who was not a Mormon, thus “called” Minerva to the artistic challenge she already sought by temperament and talent. This “calling” was reiterated several times in her life through dreams and dramatic events (1937, 19, 21). She returned to the West -— to the Indians, animals, and hard life on the land, and the association with strong men and women who were living links to the history of her homeland and church.

Returning to Pocatello in May 1916, Minerva opened a portrait studio in the home of Dr. Minnie Howard, a physician and chairman of the Idaho Arts Commission. These early portraits are “candid” capturings of individual ex pressions with heavier color application than she would use later, indications of Henri’s influence. Commissions came quickly, and she soon exhibited twenty-six paintings in Boise. The Boise Idaho Daily Statesman on 16 February 1917 published a review of her work to date: “Her portraits are in the broad style so much in vogue among the modern American artists, and they need to be viewed from considerable distance in order to get their splendid effect. . . . The strong note of color in Miss Kohlhepp’s portraits is wonderfully pleasing.”

Then on 15 September 1917 Minerva married Herman Teichert, who had waited faithfully for her while she had commuted between East and West for five years. As a war bride, Minerva journeyed with Herman to Ft. Lewis, Washington, where he received basic training. When he was sent to France, Minerva returned to American Falls, where their son Herman was born on 1 July 1918. During the influenza pandemic, both Minerva and little Herman became desperately ill. In her autobiography she recalled:

The armistice was signed, my husband was on the way home from France, and I now had a son. It seemed I was sinking so fast when I thought of prayer. I thought of my years of study and so I had done nothing with my art education. Suddenly I was keenly sensitive. I promised the Lord if I’d finished my work and he’d give me some more, I’d gladly do it. With this covenant in my heart I began to live (cl937, 19).

Her hair turned white during her illness, a sign, she believed, of her covenant.

After Herman’s return, the little family moved to the old Teichert ranch on Fort Hall Bottoms, Idaho, where Robert (named for Robert Henri), Hamilton, and Laurie were born. Herman was a quiet man of physical and spiritual strength, characterized by Minerva: “His lack of schooling gave him few opportunities but I knew [that] his skill in many things and his manhood would do much for him. . . . Herman has always given me a free rein to do what I please and so I try to please him which I would not do if he tried to ‘manage’ me” (cl937, 16-17). Thus, Minerva kept full responsibility for cooking hearty meals for Herman and the hired help, cleaning, tending the chickens and the milk house, gardening, and caring for children. But she was free (especially in the evening, when she often put the children to bed early) to use precious spare moments for her painting.

Robert Henri kept in touch with his protege. He encouraged her to continue her artistic work and even proposed in 1924 that she accompany him and his wife to England. With Herman’s encouragement she began making plans to go but had a dream about a little girl in a pink dress whom she believed was her unborn daughter. She refused the opportunity, and Laurie was born a year later. Minerva later painted her in pink.

Fort Hall Bottoms was on one side of the Snake River with the Shoshone and Bannock reservation on the other. The ford in that location was popular, but the river could be treacherous (R. Teichert 1987). In 1926, water from the new American Falls dam flooded their land permanently, forcing them to start over elsewhere. Minerva preserved that period of their married life in Drowned Memories (1926), a loving description of the country, trees, and terrain, not only in words but in drawings of landscapes, buildings, and resi dents. Her romantic introduction describes a story and characters which

shall be heard of only in tradition. . . . The Indians tell of a time when all western waste was as beautiful and green as the Bottoms is, but they fought, and killed, angered the Great Spirit until forest fires destroyed the forests and out of the ashes the sage-brush grew. It has ever since been a symbol of dust and ashes. . . . in modern times we have found happy homes here, and on the Teichert ranch where my husband grew up—he and his brothers and sisters—just as my own little ones are growing up, there is still the blessing that the “Great Spirit” left (1926, 7).

The family moved to a ranch in Cokeville, Wyoming, in 1927. Their fifth child, John, was born there, and Minerva wrote A Romance of Old Fort Hall (1932), a novel set in their Idaho home, and illustrated it with sketches.

In 1933, Herman joined the LDS Church and was almost immediately called to the bishopric of their ward, where he served for more than twenty years. Minerva, who had gained a great appreciation for music and theater in Chicago, was frequently involved in ward and school productions and pro grams. She had always been deeply devoted to the gospel; she felt that one of her spiritual gifts as a wife and mother was receiving promptings and guidance through dreams. For example, she had dreams about all of her sons’ future wives. She also fervently believed in prophecy.

She knew how to tell, write, and paint a good story. Years of teaching gave Minerva a straightforward narrative style that helped her accomplish her goals, which were often didactic. Minerva did most of the talking when in the company of her friends and relations, which they accepted because as one man put it, “She was always interesting.” Energetic and charismatic, Minerva was “passionate” on her three favorite topics: “the Gospel, politics, and art” (R. Teichert, 20 Nov. 1985). Not surprisingly, in choosing subjects to paint she opted for what she considered to be the most dramatic moments.

She was a political activist on the conservative end of the spectrum, writing strongly worded letters to her political representatives on water rights, schools, Indian rights, grazing rights, and Social Security (which she believed was unconstitutional). She conceived of her family’s wealth as “chiefly spiritual,” yet she shrewdly helped Herman as an active partner in acquiring land in four different states, at least partially with income from her paintings (M. Teichert to “Senators,” 1951; to Lisonbee, 25 Jan. 1945).

Minerva also used her paintings to defray tuition expenses at Brigham Young University, both for her own children when they became of college age and for other youngsters who she felt deserved an education but who were lacking in funds (Shoppe and Shoppe 1974, 2).

Minerva’s Professional Career

As her children grew older and more self sufficient, Minerva increasingly spent more time painting. As early as 1931 she was befriended by Alice Mer rill Home, a self-appointed preserver of the arts in Salt Lake City, who hence forth acted as Minerva’s agent and promoter. Mrs. Home, for example, would organize exhibitions at the department store ZCMI’s Tiff an Room, where she would show a number of “inland empire artists” (as she described them). She also placed paintings in libraries, schools, and public buildings.[4] On 8 April 1941 she wrote Minerva, “I am lending Mary and Martha to Edge hill Ward for Easter. Hope they will keep it. . . . Have you any sheep around? A small mural with one black sheep or two or more white lambs would be sweet” (Home to Teichert 1941). But it was a measure of the isolation Minerva worked in as a professional that Mrs. Home never, during their long relationship, visited Minerva at her Cokeville ranch.

Although Minerva continued to paint floral scenes for her friends, especially as wedding presents, and the western scenes that were so close to her daily living, it is during this middle and later period that her interest in depicting scenes from the Book of Mormon developed into what became a comprehensive painting program of heroic dimensions. Two trips to Mexico enriched her understanding of architecture and decoration as sources for her paintings. For example, she spent the summer of 1944 painting in Mexico City while Laurie attended the University of Mexico; on another trip she visited Taxco, Mexico. She wanted to see firsthand what she considered to be the ruins and remains of the Nephite and Lamanite civilizations. The Mayan and Aztec pyramids influenced her deeply. She sketched details of the temples and other structures, getting a feel for this period of pre-Columbian art. She was not overly concerned with reproducing exact anthropological detail. Instead, she concentrated on capturing the feeling of the period, place, and people. According to Frank Stevens, who later helped her paint the LDS Manti Temple’s world room, Minerva’s paintings were dedicated to “telling the story” she felt compelled to paint as part of her “calling”—occasionally to the detriment of accuracy (Stevens, 12 Nov. 1986).

She would combine different styles of Indian pottery, basketry, and even jewelry, as in Indian Pottery and Basket Merchants; other paintings show a similar eclectic tendency. To create exotic headdresses in her Book of Mormon paintings, she took inspiration from the reliefs in ancient ruins, then added feathers and hanging elements. For example, the judges in Trial of Abinadi all have different headdresses and reveal imaginative variations of a type created in a number of other paintings. She also borrowed less exotic head pieces, footgear, and greaves (shin guards) directly from classical Greco Roman sculpture.

Unlike many western artists, Minerva was only incidentally interested in landscape. It became more of a backdrop for her figures. She was heard to observe that anyone can paint a landscape and that she did not want to waste her time when she could paint more important subjects (Stevens, 12 Nov. 1986). She was always (even from her student days) more interested in painting the human figure, and now as her career advanced, episodes from religious history fascinated her. Her desire to paint dozens of scenes from the Mormon scriptures came as a logical extension of her “calling” to serve her people and religion with her art. Her son Robert believes that this idea was developed over time rather than conceived of as an integrated thematic series. However, both orally and in writings, Minerva often quoted Robert Henri’s admonition to her to paint the Mormon story. But she was almost sixty years old when she began in earnest this ambitious series; it now appears as though her Mormon paintings must have been planned as a series from the beginning since they were all executed in the same size format. The Latter-day scriptures were very important to Minerva. She studied them regularly and could quote from them for almost any situation. Each of the paintings in this series was supported by scriptural references, which she was careful to list in her notes, together with a description of the incident depicted in her own words.

Minerva painted more than forty Book of Mormon subjects, and a special series on this theme makes up the major part of the Teichert Collection held by BYU.[5] The large (36″x48″) format chosen by the artist is indicative of her goals for this project, which she hoped would be purchased by the LDS Church for public display or for educational purposes. Many of the paintings were given by Minerva to BYU toward the end of her life, after she unsuccessfully attempted to have them displayed or published.

The quick and satisfying oil sketches for this series, now in private collections, are smaller (11″x7″) in format. In terms of Minerva’s style, the sketches are more revealing, since they clearly indicate the fine draftsman ship she possessed. A sense of movement is captured in sweeping, confident lines, with quick splashes of rich and sophisticated color added to heighten the theatrical display that was so often her hallmark. The sketches have a spontaneous, living quality which is less evident in her large-scale paintings.

It is particularly instructive to consider which episodes in the Book of Mormon Minerva chose for her paintings. Some of them, such as Nephi Leads His Followers Through the Wilderness or King Benjamin’s Farewell Address, portray familiar and predictable subjects. On the other hand, some subject choices were highly personal, such as Coriantumr, the Jaredite whose ruthless ambition led inexorably to the final battle of his people, and indeed, the ambitious Destruction of the Western Continent, where the monumental architecture shows the extensive influence of Minerva’s trip to Mexico.

It is also useful to note that Minerva found great stimulus in Jewish biblical history because her father, Frederick Kohlhepp, had read the Old Testament scriptures to his family frequently in the evening, providing Minerva with an intricate familiarity with the Bible, its personalities, and stories. We might expect Minerva to have chosen more subjects from the Bible, but when we reflect on the myriad of paintings in world art on this subject and the paucity of art on the Book of Mormon, her preference seems more understandable. Even so, she did at least ten Biblical paintings that we know of, primarily from the New Testament, and centered on Christ, emphasizing his warmth and understanding. Her well-known Queen Esther is one of the few subjects taken from the Old Testament.

Minerva loved narrative and portraying women and ferreted out barely mentioned incidents from the Book of Mormon to commemorate in her paintings. Love Story, a gypsy-like scene with musical instruments and brightly clothed dancing girls, shows a celebration between the united families of Ishmael and Lehi. Probably few other artists would select a subject with so slight a scriptural reference, but it is a splendid testament to her creative imagination. In Morianton’s Servant, she illuminates the nameless servant who reveals to Captain Moroni the dissident Nephite Morianton’s plans.

Minerva had long dreamed of being commissioned to paint murals for LDS temples; finally, in 1947, her sketches for the Manti Temple were accepted and she was commissioned to do the world room. She hired a young local artist, Frank Stevens, to serve as her chief assistant for a project that took twenty-three days of on-location painting time. But a great deal of preparation was necessary; she and Stevens built a scaffolding and covered the canvas with white lead and yellow ochre to give a light earthen color for the background. Unlike most world rooms in other temples, which focus on landscape, Minerva planned large figures with little landscape—a parade of “poverty, pride, oppression, and hatred” (O’Brien 1968, 46). She wrote to her daughter Laurie in 1946:

I have the hardest temple room I have ever seen to do, 21 ft. high, 60 ft. long, abt 24 wide. The north side wall looks gigantic. I would be scared to undertake it if I didn’t know all the artists and architects are watching me to see what I’ll do. I dare not back down. Since I have an entirely new attack on the subject, a pageantry of nations, I must get approval of the church officials.

Stevens recalls that Minerva was elated with her work and frequently said, “Look what we have coming up—move quickly!” One day, she fell off the scaffolding but was soon up painting again. “She was nervy, I’ll tell you,” Stevens recalls admiringly. When he asked her why she omitted some facial features on certain characters, she told him they were not that important for telling the story. She urged Stevens to greater heights in his supportive work: “Make those mountains look sharp. This is Zion, this is what the Lord had in mind. This is the point of the total plan. . . . Learn to draw before you paint” (Stevens, 3 Nov. 1986).

In her urgency to finish the project and meet the deadline imposed by the temple, she enlisted Herman and Frank’s wife, Nancy, to help paint in some large expanses of color. On 13 May 1947, she wrote Laurie that the four of them had “worked from 6 AM to 9 PM [and] still it was not finished.” But she was exhilarated.

Oh but I have done a terrific job. It’s wonderful that my health held up, and I was able to go through with it. The authorities could hardly realize that it was ended. They had heard that I was working very fast, and I sure did. No mural decorator in America ever beat that—nearly 4,000 sq. ft. in 23 days. They must approve before I am paid.

Their approval came, and she was paid.

In 1962 Minerva turned to another aspect of Mormon culture, the historic trek from Nauvoo to Salt Lake City. That year she published a small book of drawings and text, Selected Sketches of the Mormon March. The text is limited to short descriptions of the Mormon exodus after the death of Joseph Smith. The twenty-four charcoal sketches are well-composed and imaginative, yet they are loosely done. They depict various phases of the preparation to move westward beginning in 1846 and reveal the hardships and difficulties inherent in this massive migration. The sketches are full of realistic, on-site detail; the figures and faces are barely suggested, the sense of drama is evident. The series ends with Brigham Young proclaiming Salt Lake Valley to be their goal, as seagulls fly overhead, and women and children weep with joy.

Teichert continued painting well into her seventies and stopped only when she fell and broke her hip in 1972, when she was eighty-two. This mishap virtually ended her artistic career, and she spent her declining years in a Provo, Utah, rest home, where she finally died 3 May 1976.

And what legacy has she left, both from her earlier period and from the 1930s to the 1970s, when she pursued a professional career? In addition to the paintings and stylistic characteristics already mentioned, several other aspects of her work are worthy of discussion.

For example, Minerva often selected subjects that emphasized the role of women. Love Story is such a subject. Who else would have painted the greeting of these young people who are destined to marry? Christ in the House of Mary and Martha and The Widow of King Lahonti, both in the BYU col lection, also fit into this category. Her portrayals of Christ emphasize his warmth and understanding, especially for women and children. Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, an excellent composition, frames the scene in an archway door through which the viewer sees Christ in the kitchen with the two women. Martha is working back to the left while Mary is seated in the center of the painting, studying a scroll and listening to the Savior. She is beautiful and blonde, her back gracefully curved to draw the eye through the composition, and in typical Minerva fashion, she is dressed in red. Who but a woman artist would have placed this scene in a kitchen, emphasizing the warmth shared between Christ and the two women?

Lahonti’s queen is never mentioned by name in the Book of Mormon, but Minerva does not treat her as an “extra” in a cast of men. She centers her painting on this heartbroken woman, seating her on a throne with her children beside her. She holds a vivid red shawl, typical of Minerva’s preference for striking colors; the queen is elegant and regal, even in mourning.

The Lamanite Maidens is perhaps her most spectacular treatment of women. Here maidens dressed in white, flowing dresses dance by a reflecting pool of water, while red flowers accent the movement and add to the joyful abandon. After her trips to Mexico, Minerva also painted many Mexican girls in red and Mexican dancing girls. In addition to the sketches of Saints crossing the plains, Minerva did paintings depicting the hardships of women on the great Mormon trek of the 1840s, often using her friends and family members as models (M. Teichert to Eastwood 9 Feb. 1947). Pioneer Wash Day and Quilting at Relief Society are two such examples.

Minerva’s attention to women reflects her own deep feelings about the social roles of women, which had developed from her experiences on the frontier. Grandniece Lee Anne Hart observes: “Aunt Minerva was feisty, spunky, a hundred years before her time, especially about women’s lib and the roles women saw themselves in and what women were capable of doing” (1987). However, Minerva herself wrote in 1926, when she was thirty-eight and had been married eight years, “Although [the ‘distinguished ladies’ of Fort Hall] grew up on a cattle ranch, they never used slang nor made an unlady-like gesture. They could ride as well or better and endure as much dust and wind in an Idaho sun as any young women who now style themselves ‘cowgirls’ and yet were prepared to take a place in any society without fear” (p. 26). Thirty-five years later, on 14 March 1961, she wrote in her diary:

Relief Society—and I’m going. I talk too much—not about people but the lessons. Too bad I wasted ten years of talk in Fort Hall Bottoms. Sometimes I’d go for months and never see a woman. I don’t know women’s language very well, so I talk politics and religion. They don’t talk art or chicken talk so I’d better try to get in on this Relief Society deal more often. See you later.

A second trait of Minerva’s is that she can best be described as an illustrator and decorator, despite her scorn for artists who were mere decorators or “calendar artists” as she called them (F. Stevens, 2 Nov. 1987). The difference is that Minerva was extremely well trained while many popular illustrators of the day lapsed into sentimentality or fell into the trap of becoming clever decorators for magazines. Minerva comprised in her work the best meanings of those two terms. She had little in common with other muralists of her day in terms of style or even subject matter, but she shared with the best of them a strong sense of the relative importance of one part of a composition to another—a sense which during more than fifty years seldom failed her. She was able to fill a canvas with robust figures, animals, and architecture, telling the narrative in a straightforward and concise way and leaving detail to the imagination.

For example, in the Last Nephite, Moroni, she put Moroni, seated alone, in the center of a cave-like enclosure next to a wall by a glowing fire. Wearing a kind of bibbed top and a short skirt with a sword hanging from his belt, Moroni works with a stylus and mallet on metal plates. He is lonely in this secret location, but deep in concentration. On the wall are utensils for survival; on the floor is a rug with a chevron design, a reference to the culture of Indians she herself knew. Minerva has painted Moroni’s face so thinly that the charcoal underdrawing shows through, and much of the humble background is suggested rather than drawn.

Minerva preferred to work in oils and made large paintings, a projection of her own monumental personal goals. She painted dramatic episodes literally larger than life for public display; she wanted her art to motivate the viewer to greater faith in the gospel and greater appreciation for the pioneer heritage. Her achievement is particularly noteworthy since she painted most of her large works on a canvas or board fastened to her long, narrow living room wall. Since she could not back up far enough to see her murals as the viewer would see them, she looked at them through a reversed pair of binoculars to capture the kind of perspective she needed.

She also displayed a preference for painting narrative. In this, she differed from most painters in Utah and the region, who primarily concentrated on landscape. Among the few landscapes that she painted were those of the Teichert property on the old Fort Hall Bottoms with which she illustrated Drowned Memories and A Romance of Old Fort Hall. These same scenes also appear in a frieze around the living room in her Cokeville home. Otherwise Minerva painted landscapes as the backdrop for her vision of religious history or scriptures.

She also painted at least ninety-three portraits, which ranks her with such other Utah artists as John Hafen, J. T. Harwood, and Lee Greene Richards. One of her finest is Portrait of Sara, a tableau of a young woman presented in a yellow print dress trimmed with pale green ribbon. She is a coquette who returns the viewer’s regard with no hesitation. In the best Henri tradition, she emerges from the dark as a presence not to be denied (Henri 1951, 20-21). The detail of the dress contrasts with the less defined hair and suggestion of a tiara; the viewer can only wish for more of this Teichert vintage painting, with its direct, bold approach -— a restatement in paint of Minerva herself.

In Betty and the Seagulls, Minerva used Cokeville family friend Betty Curtis and her own son Robert as models for this painting of faith and optimism of the Mormon pioneer miracle. This work is dominated by the up lifted face of the central character, Betty, who kneels in the center of the painting in front of other figures, bowed in prayer. Minerva had a personal stake in this rendering: “In the Sea Gull painting, I thought of my grandmother, Minerva Wade, who was a young woman at the time of the cricket invasion. I heard the story from her so many times that it would be impossible not to visualize it somehow” (M. Teichert to Larsen, 1936). Jules Breton’s Song of the Lark, acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1894 (Maxon 1970, 91), shows a young woman who, though standing, has a similar lift of her head and expression of wondrous awe. This is the only Minerva painting in which a real source can be suggested. A similar work in the Church collection in Salt Lake City features daughter Laurie in the central role, but with her arms upstretched.

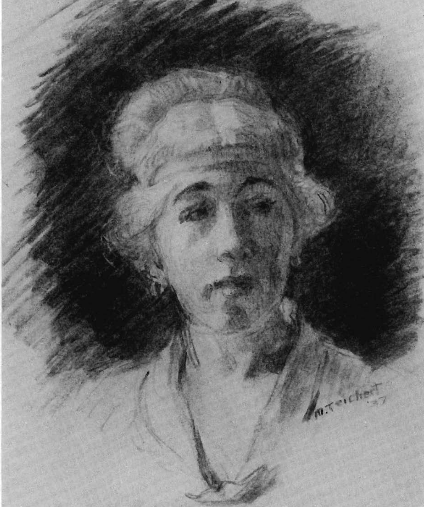

Also appealing is Minerva’s own quickly rendered Self Portrait in graphite, where her hair is piled high, with a typical ribbon or headband of cloth around her forehead, a student trademark she kept for almost her entire life (it is thought that this was a holdover from her days performing as an Indian in vaudeville in New York). Here Minerva radiates confidence. She is portrayed with an elongated neck and has poised her head in a regal position. She was very conscious of appearances and was known to give suggestions to her granddaughters on how they should walk and even hold their mouths (Wardle 1987).

Henri’s influence also appears in other portraits characterized by dark backgrounds and emphasis on the expression in the eyes. In fact, Minerva’s sitters usually confront the viewer in a straightforward manner, as if the viewer were to be scrutinized or appraised. Her subjects clearly are worldly, earthly, not formal or unapproachable as more pretentious portraits by less talented and perceptive artists often appear.

Animals for her were part of the people, not part of the landscape. She took her charcoal to rodeos and sketched horses, cattle, and cowboys. Her camels and elephants in the religious paintings are rendered with confidence, and a number of her paintings or their borders include exotic birds seen in her travels. The First Plowing focuses on sturdy, dependable oxen carrying out their age old task of helping to prepare the earth for planting. Minerva renders the anatomy of the oxen with understanding and sensitivity comparable to another Utah woman artist, Mabel Frazer, who also focused on the land and animals in her painting The Furrow.[6] Both of these artists relied on their rural background experience to create scenes of vitality and the real world of the farm. The power and strength of both of these women’s work exceeds that of most male Utah painters during this period.

Still lifes were traditionally considered a woman’s topic, since figure studies, especially, were considered off limits for women until the very end of the nineteenth century. A number of early western female artists, like Mormon painter Harriet Richards Harwood, painted almost nothing else. Minerva painted scores of floral still lifes as funeral or wedding gifts; most of them thus remain in private hands. As usual, she worked quickly, completing a painting in an afternoon while she had other paintings in process. Her love of physical beauty glows through their colors, and because they were easel paintings, they have more definition and detail than is usual in her other works. They are also evidence of one of the major purposes in Minerva’s art: that the fruits of the creation exist to enrich the lives of others, particularly the less fortunate.

Minerva was trained in the best of academic traditions—in two of the nation’s preeminent art schools and with a trio of renowned mentors; the excellence of her training is especially evident in her compositions. They are carefully balanced in a manner that derives from experience and an innate sense of completion. There are few, if any, of Minerva’s works which leave the viewer with a sense of imbalance. Most of her works are planned, utilizing a triangular or pyramidal organization which dates from the Renaissance and is considered the foundation of good composition. There is no monotony in her compositions because she varied the formats and arranged the figures in such a way that they seem natural and not in the least contrived. Occasionally she liked to use arched doorways or frames within the frames to obtain a new perspective or to create a sense of intimacy.

Minerva also displayed great skill as a “colorist.” She knew how to com bine, contrast, and highlight with colors. As a regionalist responding to her arid western setting, she employed color to stay in harmony with her environment. When she recreated her own milieu, she chose grays, blues, and pastels. Describing Idaho to her New York City classmates, she said, “There is a grey sky and grey hills covered by grey sage. An Indian rides by on a white horse with a cerise blanket” (Eastwood 1987). Minerva’s colors were subtle for the most part, but as she described the touch of color in the Indian’s blanket, Minerva used various hues of red to heighten interest and to catch the eye as it roamed across her paintings. Another example is Christ in the Red Robe, which like Mary in the Mary and Martha painting, uses red for the central figure. “At present I’m painting ‘Christ coming in his red robes,’ ” Minerva wrote to B. F. Larsen in 1945. “Don’t know what to do with it but I like it. Have to do something besides churn and figure income tax.” In a 1916 New York student sketchbook she notes: “Light red and Indian red are beautiful and permanent. Indian red, strength increases with time.”

In summary, Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert achieved a sophisticated and well-articulated program of artistic endeavor, crowning it with Mormon historical and theological themes. She gave a unique vision of the world of the Book of Mormon and her pioneer heritage, literally magnifying her calling into hundreds of paintings and leaving her personal interpretation of the gospel she loved so intensely. She carried out this program in addition to being a wife, mother, and business manager of a large ranch.

To put Minerva’s achievement into context, Helen Goodman, in a recent article on women illustrators between 1880 and 1914, observes that many women gave up their careers or dramatically curtailed them after marriage. “Those women who did persist, however, often found themselves illustrating almost exclusively themes of childhood, motherhood, romance, or fantasy.” Goodman characterized this art as charming, anecdotal, and decorative, but rarely found powerful intellectual or psychological insights or formal experimentation (1987, 15-21). Minerva never suffered from such superficiality or limitations.

Minerva’s life was not easy, and rejections of her work and talent strongly affected her. She aspired to do more paintings in an official way for the Church, but her sketches were not accepted for the Idaho Falls Temple, and much to her disappointment she did not receive the Swiss and Los Angeles temple commissions either. Nor did the Church acquire her series of Book of Mormon paintings, which would have fulfilled the “calling” she felt. In a letter to her sister Eda, she wrote about her nephew Alvin: “Hope he’ll have better luck telling the world he knows something than I’ve had” (M. Teichert c 1940). She never let herself become bitter, but she was not shy about articulating her feelings on a number of occasions.

Her isolation in Cokeville was undoubtedly a handicap in reaching a larger audience. If she had lived, for example, in a large, developing suburban area such as Los Angeles, she might have won the professional recognition during her lifetime that she sought and deserved. Yet the Wyoming isolation did pro vide her with the setting for her western-oriented paintings. And the isolation also may have stimulated her imagination. On the other hand, the critical assessment of other artists and colleagues might have pushed her to greater achievements.

The true power of Minerva’s strong faith is revealed in the creative conceptualization of more than forty scenes from the sacred record of the New World. Her imaginative Book of Mormon paintings offer a visual alternative to a generation of Latter-day Saints brought up on Arnold Friberg’s powerful but masculine imagery of the Book of Mormon. Here, surely, is one of Minerva’s “finest hours,” where she paints with Olympian nobility, with a sure touch and feel for the dramatic moment ever present. It is here that Teichert must surely join the ranks of the most creative Latter-day Saint artists—one who sought to express the unique vitality of her theology in an absolutely original mode.

[1] Much of this biographical information comes from research done by Laurie Teichert Eastwood, of San Bernardino, California, based on letters in the Teichert family collection, located in personal archives in Cokeville, Wyoming, Provo, Utah, and San Bernardino. I have also used several oral history interviews, which are listed in the bibliography.

[2] Vanderpoel had studied in Paris in 1886 with Boulanger and Lefebre. Schook taught at the institute for thirty years; Minerva took a number of his classes. She also took at least one course from Sterba, who also taught at the American Academy of Art in Chicago.

[3] George Brandt Bridgman (1864-1943) studied with Gerome and Boulanger in Paris and taught at the Art Institute of Chicago for thirty years (Bridgman 1952).

[4] In fact, South High School, North Cache High School, Logan High School, Horace Mann School, Deseret Sunday School Union, and Yalecrest Ward Chapel purchased murals with Mrs. Home’s help (Home 1941, 408-9).

[5] One problem in assessing Minerva’s entire output is that a complete catalogue raisonee of her works has yet to be completed. During the academic year 1986-87, I undertook a study and inventory of BYU’s Teichert holdings, the results of which are in the College of Fine Arts Archives. The LDS Museum of Church History and Art also possesses a major collection; otherwise, the bulk of her work is owned privately, awaiting a comprehensive inventory.

[6] Mabel Frazer served on the art faculty of the University of Utah for many years and produced a distinguised corpus of works herself. There is, however, no evidence to date that these two women—Minerva and Mabel—who were professional contemporaries, ever met or, indeed, had opinions on the work of each other. Both were strong individuals endowed with great confidence in their respective abilities and talents.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue