Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

Modern Mormonism, Gender, and the Tangled Nature of History Gregory A. Prince. Gay Rights and the Mormon Church

Few topics have dominated modern Mormon discourse as much as those related to homosexuality. Especially following the contentious and engrossing debates surrounding Proposition 8—the electoral battle in California in 2008 over the legality of same-sex marriage—the LDS Church has not been shy to step into public discourse defending what they define as traditional values. In November 2015, months after a Supreme Court decision in America legalized gay marriage across the nation, the Church established strict and, to many, draconian punishments for not only those who enter such relationships, but also tight restrictions of children raised in families with same-sex parents. And while leaders announced that the policy was revoked in 2019, LDS discourse has remained stridently traditional and entrenched, reflecting its centrality to many leaders’ thinking.

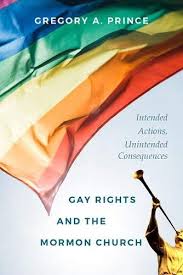

Yet while developments related to these issues over the past decade have been frequent and often furious, it is easy to lose track of the larger story, especially the events that preceded 2008. The community has long needed, then, a meticulous history of all the institutional decisions that brought the LDS Church to this point, especially one containing insider information that could flesh out traditional narratives. Fortunately, we finally have a book that fulfills this need. Gregory A. Prince’s Gay Rights and the Mormon Church: Intended Actions, Unintended Consequences is a nearly exhaustive collection of institutional deliberations and actions over the past few decades, often buttressed by interviews and correspondence that have been previously inaccessible to scholars.

The story, at least in Prince’s telling, begins with the presidency of Spencer W. Kimball, who was the first modern leader to heavily emphasize the “threat” of homosexuality. Kimball argued that homosexual thoughts and inclinations were a sin on their own and could only be overcome through repentance and righteousness. Eventually, however, Church discourse later evolved, often through the influence—or at least the voice—of Dallin H. Oaks, to argue that while sexual orientation may be innate, acting on homosexual inclinations was sinful. These two leaders, Kimball and Oaks, hover over the entirety of the book, and in many ways Gay Rights and the Mormon Church is framed as a response to these two towering figures and their still-prevalent ideas. This shift from rejecting the biological basis for homosexuality (Kimball) to begrudgingly making the concession yet trenchantly maintaining the traditional form of marriage (Oaks) is interwoven throughout the book, including some of the most painful parts of that story, like Brigham Young University’s tragic experiments with reparative therapy. Indeed, many readers will be struck by how far, and how quickly, the LDS institution has come in two decades—not to mention how recent it was that Church policies regarding homosexual members were far more draconian.

The most useful parts of the book include the exhaustive details concerning how the Church was involved in the numerous legislative and electoral initiatives throughout the 1990s and 2000s in an attempt to forbid same-sex marriage. Hawaii was the starting point, as it served as a testing ground for how LDS leaders would navigate the politics. Several lessons they learned from this episode included framing the debate as a moral rather than a civil rights issue, working in collaboration with other faiths (particularly the Catholic Church), as well as staying out of the spotlight. The Church then repeated these steps over and over again across several other states for the next decade, always to victory, and often avoiding overwhelming negative press. I was personally struck by how often BYU law professor Lynn Wardle showed up in the narrative, as he was frequently behind many of the Church’s efforts to frame their legal battles and buttress legislative initiatives; I hope scholars in the future do more to tease out his role in this complicated affair.

Things changed with the Proposition 8 campaign in 2008, when California voted on an amendment to the state constitution that would ban gay marriage. The ballot measure was prompted when a previous state law that had done the same thing, which the Church had helped pass several years before, was struck down by the state’s supreme court. Once again, local members, actively urged by their leaders, sprung to action. One study estimated that though Mormons made up only 2 percent of California’s population, they accounted for half of the Prop 8 campaign’s donations, and another calculated that they provided around 90 percent of the on-the-ground volunteers. And again, they were victorious. Yet this time, the cultural climate had changed so much that the negative backlash overshadowed anything that had come before, and 2008 became a turning point in the larger national picture, eventually leading to the 2015 Supreme Court decision that legalized same-sex marriage nationwide.

Following legalization, the LDS Church was once again forced to adapt, which required both external negotiations—like working with state politicians to support granting legal rights to LGBT persons but still maintaining religious exemptions—as well as internal practices, like the November 2015 policy that declared anyone in a same-sex marriage to be considered in apostasy, and their children barred from ordinances until they turned eighteen. Prince was able to piece together the origins of the policy by holding discussions with people “on condition of anonymity,” and it appears to have been both rushed and poorly fleshed out.[1] (Given it was repealed less than four years later, that may very well have been the case.) The blowback, of course, was monumental, and the book closes on an ambiguous note with a church and community still seeking firm land on which to stand, and without a clear path forward.

As with his previous biographies on David O. McKay and Leonard Arrington, Prince’s greatest contribution is compiling mountains of firsthand information into one place, often drawing from untapped resources. Gay Rights and the Mormon Churchwill therefore be an essential sourcebook for decades to come. But the compendium style, with short topical chapters that at times jump between decades, can make the overall narrative feel disjointed, and the lack of connective tissue between the episodes and themes can make it difficult to trace the larger trajectory. Some of the sources also raise questions. For example, footnote 39 for chapter 3 cites “Boyd K. Packer to Dallin H. Oaks, March 16, 1978,” which appears to be a private letter between the apostles. Any historian who studies modern Mormonism, though, knows that these kinds of sources are typically restricted, so there is a question of provenance. It is likely that letters like this one are what Prince is referring to when he says that “many people” had “shared with me unpublished documents,” of which he then left photocopies in his personal archive (363). It is wonderful to have access to these crucial sources, of course, but there are plenty of questions regarding where they came from and how reliable they can be.

Having said what I believe to be crucial strengths of the book, allow me to close by highlighting a few questions the book leaves unanswered. First, Prince’s own background shapes much of how he approaches the topic. As a scientist, he spends a lot of time on the biology behind homosexuality and at times even refutes the Church’s discourse point-by-point. This analysis sometimes disrupts the narrative, however, and it can overshadow the cultural dimensions of sexuality. Indeed, it also appears a bit discordant with most scholarly literature on sexuality in America, which has moved away from biological determinism in order to better capture the dynamic spectrum of gendered experience.

Another aspect of Gay Rights and the Mormon Church that makes it distinct from other works in the field is his avoidance of the broader cultural context. While the book does mention the legislative scaffolding of modern America, and Prince ably summarizes the legal and political activities in the fights for and against LGBT rights, he does not explore how the Mormon experience fits into other religious movements, particularly the religious right. In what ways did the institution borrow from the wider discourse, and in what ways did it diverge from it? For most of the narrative, the LDS Church appears to exist in a cultural vacuum.

And finally, perhaps one of the most questionable aspects of the book is its focus on men. Indeed, save for one chapter—unironically titled “What About Lesbians?”—the entire book focuses on how the Church approached gay men. Prince explains he did this “not because lesbianism or bisexuality are any less important but rather because the nearly universal focus of—indeed, fixation on—LDS Church policies, procedures, and statements have been gay men” (20). Yet that very gendered fact requires unpacking. Why does the LDS Church focus on gay men? And further, even if these policies were directed at gay men, how did they affect lesbians or bisexuals? Indeed, for a book on sexuality, there is surprisingly little gendered analysis.

It is notable that these issues that I have highlighted within Prince’s book often reflect the LDS Church itself. By making the narrative science-driven, exceptional, and patriarchal, Gay Rights and the Mormon Church is as much an extension of LDS gender discourse as it is an analysis of it. This is, in part, a result of Prince’s own interpretive approach: he often uncritically mirrors the language and arguments of those he believes to be the “heroes” of the story, usually those who pushed for change from the inside. Prince’s argument, in other words, is part of the very cause he documents. Indeed, the book opens with an anecdote that places the author in the middle of the story, making it clear that he sees himself as one of the enlistments for the battle.

As such, Gay Rights and the Mormon Church is a pretty powerful addition to that message. This is an important book in the constant, complicated, and dynamic dialogue regarding homosexuality and modern Mormonism. Further, this compendium of “actions” and “consequences” will be immensely useful in the discussions yet to come, as I doubt the tensions at play will disappear any time soon.

Gregory A. Prince. Gay Rights and the Mormon Church: Intended Actions, Unintended Consequences.Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019. 416 pp. Hardcover: $34.95. ISBN: 978-1607816638.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Among these anonymous sources seems to have been an apostle, as Prince quotes “one Quorum member” without any citation (259–60).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue