Articles/Essays – Volume 47, No. 4

Mormon Feminist Perspectives on the Mormon Digital Awakening: A Study of Identity and Personal Narratives

Abstract

This study examines online Mormon feminists’ identities and beliefs and their responses to the Mormon Digital Awakening. This is the first published survey of online Mormon feminists, which gathered quantitative and qualitative data from 1,862 self-identified Mormon feminists. The findings show that Mormon feminists are predominantly believing and engaged in their local religious communities but, are frustrated with the position of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on gender. Many Mormon feminists participate in activist movements to raise awareness of gender issues in the Church, and this study records their responses to these recent events. It is argued that Mormon feminists play a significant role in the LDS Church as they bridge the gap between orthodoxy and non-orthodoxy and between orthopraxy and non-orthopraxy.

Keywords: Mormon feminism, activism, LDS Church, identity

Introduction

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the LDS Church), whose members are referred to as Mormons,[1] officially claims a membership of over 15 million individuals worldwide.[2] Mormon women are sometimes falsely represented as a homogeneous, orthodox, and conservative group.[3] Some of the literature brings this diversity to light, but only in a limited way. Although the contemporary Mormon feminist movement has been around since the 1970s, nowadays the internet and social media bring together large numbers of men and women who self-identify as Mormon feminists and who challenge traditional perspectives and roles of Mormon women.[4] Online Mormon feminism is a growing, internet-based movement that saw an explosion of activity in 2012. Recent social media campaigns initiated by Mormon feminists have sought to create greater equality in LDS Church policy and practice. The study described in this paper asked Mormon feminists about their identity and their responses to the Mormon Digital Awakening, including their opinions on current changes in Church policy and their internet-based Church member activities.

Previous scholarship often references the oxymoronic dilemma of being Mormon and feminist but has rarely probed the public identity of Mormon feminists as individuals or as a group.[5] Recent activist campaigns reflect a significant new development in Mormon feminist public identity, and Mormon feminists express a variety of opinions on the campaigns and recent changes in Church policy, but none of the literature has yet addressed these issues.

Few articles refer to Mormon feminists. One study divides Mormon women into three groups but does not allow the subjects to self-identify to which group they belong.[6] Mormon feminists become Mormon feminists when they self-identify as Mormon feminists, and not by any other measure. Mormons with feminist leanings who do not identify as Mormon feminists are not Mormon feminists, even if they hold the same views and religious beliefs as Mormon feminists. Identifying as a Mormon feminist may bring social and religious risks, as feminists were once viewed as a “danger” to the Church.[7] Studies on Mormon women, Mormon feminists, or any sub-group of these categories should allow individuals to speak for themselves in order to gain insights into their lived experiences as Mormons.[8]

Mormon feminists, male and female, are gaining visibility within the LDS Church and the public sphere.[9] The internet and social media are bringing together existing feminist groups and previously-isolated individuals in new ways. Some scholarship hints at the effects of the internet and social media on Mormon feminism as a movement,[10] and new research details the role of social media in the creation of Mormon feminist activism.[11]

This study addresses the identity and responses of women and men who call themselves Mormon feminists. The qualitative data collected from open-ended responses in the survey explore a central question: how are Mormon feminists responding to the Mormon Digital Awakening? In order to understand this question, four related sub-questions are addressed:

Who are Mormon feminists?

What do Mormon feminists believe?

How do Mormon feminists feel about Mormon feminist activism?

How do Mormon feminists feel about recent changes in LDS Church policy?

Literature Review

Previous scholarship has addressed the internet-based Mormon feminist movement that emerged in 2004 and continues to grow.[12] Most scholarly discussions of contemporary Mormon feminism and its role on the internet occur during conferences, and while some are audio-recorded, they remain unpublished.

Several articles address the existence of Mormon feminism, which many see as an oxymoron.[13] Hoyt explores Mormon theology and identifies room for feminism while acknowledging that certain types of feminism set religious Mormon women at odds with some of their fundamental beliefs, such as rigid gender roles.[14] Vance traces the evolution of gender roles in LDS Church periodicals, showing that Mormon ideas about women were more expansive—encouraging participation in education, politics, and professional work—in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but had moved away from that position by the 1940s.[15] Mihelich and Storrs[16] examine how Mormon women navigate the perceived conflict between education and traditional gender roles in the LDS Church, while Merrill, Lyon, and Jensen[17] find that higher education does not act as a secularizing influence on LDS men and women. Avance[18] addresses official LDS Church language and rhetoric in discussions of modesty.

Anderson[19] investigates the place of women in scripture, specifically in uniquely Mormon scripture such as the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants. She states that the lack of women in such scriptures is a hindrance to women feeling fully integrated in the Church. In a separate article, Anderson[20] outlines feminist problems associated with a lack of understanding about Heavenly Mother, the eternal companion of God the Father in Mormon cosmology, emphasizing that this makes many LDS women unsure of their own eternal fates.

Young[21] addresses the LDS Church’s role in the defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment, while Bradley[22] exhaustively chronicles the same subject in a lengthy book, which Vance[23] describes as “[the] most significant examination of recent Mormon women and history.”

Chadwick and Garrett[24] look for patterns of employment and religiosity among Mormon women, concluding that full-time work negatively affects religiosity and that “[s]tronger religious beliefs were related to lower labor force participation.” Chadwick, Top, and McClendon’s[25] extensive, multi-staged study on teenage and young adult Mormons spanning seventeen years and three countries is the largest study of its kind with more than 5,000 participants. It includes interviews with unmarried mothers in Utah and a survey of former LDS Church missionaries in the United States. Beaman’s interviews with twenty-eight Mormon women reveal diversity among that group, which includes feminists.[26]

McBaine’s interview transcripts show the diversity of Mormon women living outside the United States.[27] Bushman and Kline’s collected essays focus on themes gathered from a large body of interviews with Mormon women,[28] while Hanks’s compilation and analysis of Mormon feminist voices reveal their self-confessed or asserted feminist identity from Mormon origins to the 1990s.[29] These studies, as well as the Beaman article, allow Mormon women to speak for themselves.[30]

Methods

Data collection for this study was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, the investigators created an online survey using Google Forms and invited Mormon feminists aged eighteen and older to participate. For the purposes of this study, a Mormon feminist is anyone who identifies as such or who considers him- or herself to be both a feminist and a Mormon. Links to the survey were posted on social media sites associated with Mormons and Mormon feminism, including blogs and Facebook groups. Owing to the hidden nature of the Mormon feminist population, this study employed snowball sampling. The survey was posted on July 7, 2013, at 5:00 p.m. MDT and closed on July 14, 2013 at 5:00 p.m. MDT. The following blogs posted links to the survey: Feminist Mormon Housewives, The Exponent, Mormon Women Scholars’ Network, Nickel on the ’Nacle, and Modern Mormon Men. The investigators posted a link to the survey on the following Facebook groups on July 7, 2013: Young Mormon Feminists, Feminist Mormon Housewives, fMh in the Academy, MoFAB, All Enlisted, Exponent II group, Mormon Stories Sunday School Discussion, The Mormon Hub, A Thoughtful Faith Support Group (Mormon / LDS), Supporters of Ordain Women, Mormon Feminists in Transition, MO 2.0, Exploring Sainthood Community | Mormon/LDS, and Mormon Stories Podcast Community. Tracking of social media was not possible in this study.

The purpose of this survey was to gather a broad range of data unavailable in other studies, including the size of the online Mormon feminist community, demographic information, reports of public and private religiosity, feelings about current gender roles, and reactions to recent Mormon feminist activism and policy changes in the LDS Church. Owing to the complex interaction of feminism and religion, this survey contained both open-ended and closed questions, allowing for a more complete understanding of the quantitative data sets. The investigators reviewed the survey (n=1,862) to ensure that respondents understood the bounds of the study and removed three individuals who were too young to participate. Google Forms provided an analytic tool for the closed questions. The open-ended questions were analyzed in order to identify common themes, tone, and depth of responses. This information was used to create a qualitative codebook to ensure inter-coder agreement. The spreadsheet results were converted to a database and queried using SQLite.

Analysis of the data led to the creation of a second survey to reach a more nuanced understanding of the complexity of Mormon feminist identity and experience. One hundred of the initial respondents participated in follow-up interviews via email. Selection of these respondents was based on the diversity of their responses in order to counter the potential bias of snowball sampling. The interviews consisted of twelve open-ended questions relating to respondents’ personal definitions of Mormon feminism, feminist awakening, interactions with other Mormon feminists online, Church background and activity, further responses to the Mormon Digital Awakening, consequences of participating in Mormon feminism, and hopes for the future. Fifty-four follow-up responses were received, which were examined for quality, reliability, and consistency. Five were removed due to duplication and two for blank responses. The remaining forty-seven responses were analyzed, and primary and secondary codes were developed to ensure inter-coder agreement, allowing for the identification of recurrent themes and patterns.

Findings

Demographics

The existing literature does not provide an estimate of the size of the Mormon feminist population. This survey specifically targeted Mormon feminists who use social media. The respondents were overwhelmingly female (81 percent) with a significant minority of males (19 percent). They ranged in age from eighteen to seventy seven, with 79 percent aged forty or younger. Ninety-five percent resided in the USA and the remainder in nineteen other countries. Ninety-one percent identified as white/Caucasian. Mormon feminists are highly educated, with 79 percent of respondents holding a bachelor’s degree or higher. Their pre-tax household income levels were spread relatively evenly across all brackets, except that 24 percent report a yearly income above $100,000.

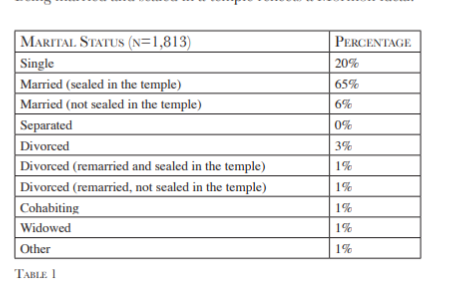

Forty-two percent of respondents work full-time and 16 percent work part-time. Nineteen percent were stay-at-home parents, of whom 98 percent were female and 2 percent male. Sixty-two percent of respondents were parents, with numbers of children ranging from one to eleven. Sixty-five percent of respondents reported that they were married and have been sealed in an LDS temple (see Table 1), compared with 45 percent of Utah-based Mormons.[31] Mormons believe that the sealing ceremony binds couples for eternity together with their children or future children. Being married and sealed in a temple reflects a Mormon ideal.

Table 1

| Marital Status (n=1,813) | Percentage |

| Single | 20% |

| Married (sealed in the temple) | 65% |

| Married (not sealed in the temple) | 6% |

| Separated | 0% |

| Divorced | 3% |

| Divorced (remarried and sealed in the temple) | 1% |

| Divorced (remarried, not sealed in the temple) | 1% |

| Cohabiting | 1% |

| Widowed | 1% |

| Other | 1% |

Religiosity

Eighty-seven percent of respondents were baptized at the age of eight, the typical age for baptism in the LDS Church, and likely grew up in LDS families. Several previous studies have suggested, directly or indirectly, that Mormon feminists are inactive Mormons.[32] This was found to be untrue. Eighty-one percent of respondents attended church at least two or three times per month (see Table 2), compared with 77 percent of US-based Mormons, who reported attending church once a week,[33] though it is important to note that people often over-report church attendance.[34] Seventy-one percent held current callings, and 97 percent have held a calling in the last ten years. Rather than simply attending church, a majority of respondents was engaged with their local Church communities.

Table 2

| Church Attendance (n=1,858) | Percentage |

| I attend church every week | 55% |

| I attend church nearly every week | 19% |

| I attend church 2–3 times a month | 7% |

| I attend church once a month | 3% |

| I attend church a few times a year | 6% |

| I attend church church once a year | 1% |

| I do not attend church | 8% |

The survey asked respondents about their beliefs, requesting them to check boxes next to statements with which they agreed. These questions were drawn from Chadwick and Garrett’s study,[35] which found that three-quarters of women strongly agreed with all of the belief statements and that the remaining quarter fell into a category which they labeled “less than very strong belief.” Mormon feminists who use social media today have a different belief profile. Fifty-six percent of respondents checked all of the boxes, indicating that they have a very high degree of belief (see Table 3). Eight percent did not check any box, indicating that they do not have beliefs associated with the core tenets of the LDS Church. This group included 152 respondents, of whom 32 percent were male and 67 percent female, with one percent not reporting their gender. Surprisingly, 43 percent of those with no belief attended church at least two to three times per month. This may be an indication of social pressure to conform to Mormonism or of the benefits of belonging to a religious community.

Table 3

| Level of Belief (n=1862) | Percentage |

| None | 8% |

| Low | 15% |

| Moderate | 10% |

| High | 11% |

| Very High | 56% |

Table 4

| Belief (n=1,710, excludes respondents with no belief) | Percentage |

| There is a God | 98% |

| There is life after death | 97% |

| Jesus is the divine son of God | 90% |

| I have the opportunity to be exalted in the celestial kingdom (heaven) | 78% |

| Joseph Smith Jr. was a true prophet | 75% |

| The Book of Mormon is the word of God | 75% |

| The Doctine & Covenants contains revelations from God | 73% |

| The Church today is guided by prophet/revelation | 70% |

| Thomas S. Monson is a true prophet of God | 70% |

| The LDS Church is the restored church | 69% |

Another way to view the data is to examine the percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement (see Table 4). The three statements of belief held in common with many other Christian denominations received much higher percentages of agreement than the other statements. The three statements with the lowest agreement are uniquely Mormon beliefs associated with how respondents perceive the Church’s actions today.

Issues of Mormon Feminism

Mormon feminism is not clearly defined in the literature. When asked, the respondents repeatedly defined Mormon feminism as an active and faithful search for equality inside the LDS Church. One respondent offered this definition:

Finding nobility, beauty, and empowerment in uniquely LDS doctrines about gender: the existence of a Heavenly Mother, godhood as a partnership between men and women, the body (both male and female) as a gift from God that is necessary for eternal progress, and an interpretation of the Fall in which Eve plays the role of a courageous risk-taker who chose to sacrifice paradise for her family. . . .

Beyond the definition of Mormon feminism, the investigators explored the personal narratives of the individuals regarding how they had come to identify themselves as Mormon feminists. The personal stories of Mormon feminists are compelling because their journeys into feminism typically begin with the orthodox practice of Mormonism. These individuals express tension between Mormon belief and the practice of gender in the LDS Church. The following are samples of selected responses by women:

It was a process. Two years ago, I would have regarded someone who believed in female ordination [as] an apostate. As I continued on in my personal study of scripture and Church history, some things just didn’t make sense to me. I felt the Lord directing me to questions and conversations that made me really think about my place in the Church. As I moved into a family ward from a student ward, I was called as a 2nd counselor in the Young Women’s presidency. I started experiencing negative effects of gender inequality and the Church. As I considered these experiences and brought them in prayer to my Heavenly Father, I felt very strongly that He did not regard me differently as a female. I felt the church leadership as a whole did, though. That struck me as off. The more I discussed my questions and feelings, the more I realized that the LDS church, for all it’s [sic] restored truths, was missing feminism.

What really got me asking questions was one day when my husband and I had an argument in which he insisted that I didn’t respect his Priesthood authority and that since he was the man, I had to do whatever he said. On a separate occasion, a man treated me to a discourse about how women are less capable of spiritual growth than men because they don’t have the Priesthood. I defended myself by saying that I made the exact same covenants in the temple that he did, but when I took a closer look I realized that this is not entirely true, and doubt crept in. I know in my heart that what they said can’t be true, but it was shocking to encounter men in the church who felt that way.

The respondents have other concerns regarding the treatment of women in the LDS Church. These include the fact that the Relief Society, the LDS Church’s women’s organization, lacks autonomy, and respondents feel their potential is undervalued. Many respondents observed similar problems in the youth organizations, noting a funding disparity between the Young Men and Young Women programs. Their reported observations included a lack of leadership training and meaningful service opportunities for young women and rhetoric about modesty that respondents felt was shaming and objectifying. Others noted problems such as equating womanhood with motherhood but without support or respect for the challenges of motherhood, including public breastfeeding, the absence of infant changing tables in men’s bathrooms, the poor quality of nursing facilities in Church buildings, and not emphasizing or preparing men for fatherhood.

LDS temple ceremonies also cause difficulties for many respondents. Problematic policies mentioned include: prohibiting women from remarrying and having a new sealing unless they receive a cancellation of their previous sealing from the First Presidency (the highest governing body in the Church), no possibility of civil marriages immediately preceding a temple sealing in the US and Canada, and the placement of men as intermediaries between women and God in temple ceremonies. As they do not hold the priesthood, women are excluded from some Church councils and many leadership positions. Even when the Church makes policy changes that seek to restore a gender balance, the conservative nature of local leadership may prevent these changes from being enacted. Some respondents reported that Church teaching does not emphasize the mission and message of Christ. Others expressed concerns about the lack of transparency regarding Church finances and history, specifically regarding greater roles for women in the past.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is unusual in that it does not have a professionally-trained leadership. Since 1978, all men aged twelve and older have had the opportunity of being ordained to the priesthood,[36] which confers administrative and ritual authority. In 2006, an American religious survey reported that only nine percent of Mormon women and 53 percent of men were in favor of women holding ecclesiastical office in the LDS Church.[37] The current study tried to capture the prevailing opinions of Mormon feminists and asked a similar question. Eighty-four percent of respondents reported a belief that women would, at some point, hold the priesthood (see Table 5). Mormon feminists, at much higher rates than a random sample of Mormon women, believe that women will be ordained.

Table 5

| Whether in this life or the next life, do you believe that women will some day hold the priesthood? | Percentage |

| Yes, in this life and in the next life | 43% |

| Yes, but only in the next life | 14% |

| Yes, but only in this life | 2% |

| No, I do not think that women will some day hold the priesthood | 16% |

| I feel that women already hold the priesthood | 26% |

Identifying as a Mormon feminist often imposes a heavy social cost, and 56 percent of respondents reported that they have experienced negative consequences as a result of expressing feminist views. The most common are social ostracism, loss of callings, loss of friendships, exclusion from the temple, and family pressure. Several respondents shared the various consequences they have experienced.

The most negative experiences that I have faced deal with [M]ormon men being taught that women who are educated and pursuing careers do not want to get married or would not be good mothers. I’ve been told by over 50 men who I dated that my PhD from Harvard was a selfish pursuit. I’ve been told that “You are the most Christ-like person I have met, but you don’t know your role as a woman. I could never marry a woman who doesn’t follow her role.” I served a mission. I kept the rules. I also followed my talents and directives of my blessings. I believe God is pleased with my efforts. But the Proclamation on the Family has been used to hurt me countless times. The way that the Church has stressed gender roles has hurt me badly enough that it challenges my belief in the organization. (female respondent)

I was taken off the program to speak at church and pulled into my bishop’s office for a meeting. While he expressed a desire to understand, his demeanor and comments were anything but understanding. I felt belittled and very small in that room. I have struggled with not wanting to attend church since this happened. The views I expressed were simple concerns about some things that I experienced in the Young Women’s program and hopes that these things would not happen to my daughters. (female respondent)

I was in a student ward at BYU. As a result of my comments, the bishopric refused to speak with me about anything. (male respondent)

My non-feminist wife is upset with me. (male respondent)

Activism

Blogs emerged in the mid-2000s, and Mormon feminists created new spaces in which to discuss feminism semi-anonymously, helping assuage some of their fear. It would take eight years of blogging and using social media before Mormon feminists engaged in their first activist movement (see Graph 1). This was simple in its aim: to attempt to document the various policies regarding menstruating young women and their participation in temple baptisms. When asked why individuals participated, many women shared personal experiences of feeling humiliated, dirty, confused, and seen as unworthy as a result of these policies.

I had a negative experience nearly 30 years ago as a Young Woman at the Salt Lake Temple, where a matron asked any menstruating girls to step out of the baptism line. We were told they were “unclean” and couldn’t do baptisms. I was already having a hard enough time emotionally and physically dealing with my new cycles. I didn’t need being told I was spiritually unfit thrown on top of that. (female respondent)

I have 4 daughters, the oldest of which is 13. I never want her to experience the public shaming perceived by others I’ve heard of on FMH (Feminist Mormon Housewives), Facebook and elsewhere (male respondent).

[Editor’s Note: For the graph “Participation in Mormon Feminist Activism,” see PDF below, p. 60]

Readers of the blog Feminist Mormon Housewives contacted temple officials at a large number of LDS temples. They requested information regarding specific policies on the participation of menstruating women and girls in temple baptisms, which are performed by immersion in pools of chlorinated water. The LDS Church responded with an official statement clarifying the policy: “The decision of whether or not to participate in baptisms during a menstrual cycle is personal and left up to the individual.”[38] Eighty-two percent of those who were aware of the temple baptism action regarded it as successful.

On the heels of the temple baptisms, a petition was started, titled “All are Alike unto God” from a scripture found in the Book of Mormon (2 Nephi 26:33). It called for a series of changes similar to those identified in the issues of Mormon feminism in this paper, allowing people to sign their names in support. The following is a response about why this supporter chose to sign the petition.

I have [a] very strong feeling that the Church needs to make changes in regards to gender equality and with inclusion as a whole. I agree with all the goals set by the petition and the realization of these would make the Church a nicer place to be. My heart and spirit tells [sic] me that I am equal to any man. I was ready to leave the church and remember crying my heart out to my Heavenly Parents. I asked them to let me know if I really was unequal to the men in my life, if that was my destiny—to not have the ability to lead and make decisions that were important to my family. My heart was flooded with such comfort and reassurance that any cultural inequality in the church did not reflect my actual standing as one of God’s children and that I should be patient as things changed. I feel like every step we make toward giving women a greater voice make [sic] our church continually more inclusive and better for women and families. So, I was happy to add my voice to ask for more voice for women in the church.

The petition received 1,035 signatures. Forty percent of participants in the current survey reported feeling that it had been a successful campaign and 24 percent had participated.

On December 5, 2012, Stephanie Lauritzen responded to two recent articles questioning the logic of Mormon feminists.[39] Four days later, the group All Enlisted launched a Facebook page, Wear Pants to Church Day, scheduling an event for Sunday, December 16, 2012.[40] There is no official prohibition against women wearing pants to church. In 1971 the First Presidency issued a statement specifically permitting the wearing of pants and admonishing members not to be judgmental.[41] In response to Wear Pants to Church Day, Scott Trotter, an official LDS Church spokesman, stated that members are simply encouraged to wear their best to Sunday meetings.[42]

However, there are strong cultural expectations in many LDS communities that women should wear skirts or dresses to Sunday meetings.[43] The intention of Wear Pants to Church Day was to encourage a small push against Mormon culture. The public backlash included insults, the questioning of faithfulness, and death threats.[44] Many respondents stated that they had previously been unsure about participating but that the hateful comments moved them to action. The first response below expresses one woman’s powerfully conflicting experience of Mormon feminist action. The second response is from a man who wants his daughter to be treated equally.

This is the one event I participated in openly, and it scared me to death. I participated mostly in response to the vitriol I read from members of the church against the movement online. I could not believe what I read. It is sickening and terrifying to know that people in your ward—maybe even people you think of as friends—might see you as unworthy or a tool in Satan’s hand, might wish you gone from the church if they knew you had unorthodox views about women’s position in the church. I had mixed feelings about the efficacy of the campaign, but I felt it important to stand up to such violent expressions of hatred. I wanted to be sure that if any women in my ward had been reading the things I had been reading or had doubts about women’s role in the church and wondered if anyone at all was on their side, that they had at least one person in the ward they could talk to. I had 3 boys, but when our daughter was born, I started to see the world in a whole new light. I tried to see the world through the eyes of this little girl, and it seemed like there were so many things that were so blatantly unequal and unfair to her, just because she is female. And to see what she is going to walk through as a girl growing in and through Mormonism . . . there’s just a lot that is so un-Christlike. I can’t change all this, I can’t change the situation, but I’m aware and I see it and I’m going to try to make it better for her.

Forty-two percent of respondents to the survey said that they had participated in Wear Pants to Church Day. Forty percent of the survey respondents thought that Wear Pants to Church Day had been successful. Of those who participated, 80 percent felt that the action was successful.

After Pants, a letter-writing campaign called Let Women Pray sought to address the lack of women praying at General Conference, the semi-annual Church-wide meeting. The 2010 revisions of the Church Handbook of Instructions 2 specifically permits women and men to say opening and closing prayers in church meetings.[45] The letters were addressed to members of the First Presidency, the Twelve Apostles, the Relief Society General President, and the Young Women General President. Women speak at General Conference, though their numbers are small; however, a woman had never prayed in 182 years of General Conference proceedings.[46]

Thirty-seven percent of survey respondents participated in Let Women Pray. The following are examples of why people chose to participate.

I participated because it breaks my heart that so many people hadn’t noticed, and even more people got upset at the idea of asking for women to pray. (female respondent)

Because sisters—especially our young sisters—needed to know that they, too, can call up God for the good of the church. And not feel like being a woman in God’s church is to be a second class citizen. (female respondent)

My teenage daughters were embarrassed by my Pants to Church [sic] participation, so the Pray campaign was a good way to show them why I had done so. (male respondent)

Ninety-eight percent of those who participated in Let Women Pray felt that it had been successful, and two women did pray during General Conference in April 2013.[47]

The Ordain Women movement strikes at the heart of Mormon theology: the priesthood. Although the Mormon priesthood has a long history of adaptation, it is seen as the backbone of Mormon male identity.[48] The issue of ordination is highly contentious even within the Mormon feminist community. The Ordain Women movement began with a website allowing individuals to post profiles stating why they support female ordination. Only 12 percent of respondents had participated in Ordain Women. The following are two examples of respondents’ reasons for participating.

There was an elderly woman in a previous ward I was in who, whenever the 1978 revelation about black members was mentioned in class, she would always comment about how happy she and her neighbors were when they heard about it. She said they ran out into the streets. She proudly told this story many times in that ward and I silently swore to myself that I would share the same story when I am old: that my neighbors and I ran and shouted and danced in the streets when women received the priesthood. So when the opportunity came to participate in Ordain Women, I made sure I was there with the first 16 profiles. I am all in. (female respondent)

Performing priesthood ordinances for my children is the pinnacle of my religious experience. There is nothing I desire more than for my wife to join me in those experiences and for my daughters to grow up having the same spiritual experiences that are available to their brothers. I also see significant additional good that will come to church by including women within leadership roles that require priesthood authority. For example, I currently serve as a bishop. My ability to guide the ward would be greatly improved if I had one or more female counselors. (male respondent)

The reasons stated for not participating were similar to those for previous actions: fear, social cost, incomplete formation of opinions, discomfort with petitioning the LDS Church, and discomfort with the inherent inequality in a priesthood in contrast to a priestesshood. Nineteen percent judged it a success, but many respondents stated that it was too soon to determine success.

“I’m a Mormon Feminist” was inspired by the LDS Church’s “I’m a Mormon” television and social media campaign. It was similar in that it provided a webpage for individuals to post personal profiles explaining why they are Mormon feminists. Within the LDS Church, feminism has negative connotations and is seen as anti-family and anti-motherhood,[49] but this campaign tried to combat such ideas. One participant stated his motivation:

I wanted to show solidarity with other similar-minded people who believe that cultural practices limiting the roles and behaviors of males and females solely on the basis of sex are harmful to all. As a male Mormon feminist, I also wanted to highlight how gendered cultural practices harm males and females, and participating in the “I’m a Mormon Feminist” campaign was a way to help highlight this.

Fewer survey participants (59 percent) were aware of the “I’m a Mormon Feminist” campaign than any other Mormon feminist campaign.

Responses to Changes in the LDS Church

In recent years the LDS Church has altered Church policy and procedures to reduce some of the inequality. The survey participants were asked whether local leaders include women in their wards, with 58 percent selecting “Yes, they feel that their local leaders include women in ward-level decisions.” The survey then asked participants specifically about their interactions with local Church leaders in expressing feminist concerns. Sixty-two percent of respondents said that they had shared their concerns with local leaders. Of these, 37 percent said that they had been heard and that their leader had made changes.

Several respondents reported transformational experiences as a result of participating in Mormon feminist activism. They describe their decision to participate or their actual participation using the same language employed by many Mormons to describe faith experiences.

I was very conflicted even up until the night before about whether to wear trousers or purple. My daughter was aware of the campaign however; it was only when I climbed into bed the night before that a feeling of calm came over me. I knew I was going to wear trousers, needed to wear trousers. Both for myself, to break out of the constraints I felt binding me, and had been chafing under for years, and especially for my daughter, who needed to see me break out, and not continue as [a] partner in my own imprisonment. I’ve pretty much been wearing trousers ever since, and it’s like I’m a different person. More outgoing, happier, more confident. Not so crushed. And I’m really surprised that’s the case.

This has been a problem for me since I came to activity in the church at age 14. This campaign was an answer to prayer for me. As a woman, I have always felt unequal in the church, and this was a way to step out and become actively involved in what I believe is the crucial means for women achieving equality.

It was a really special experience to write letters directly to people who had indirectly played a significant role in my religious experience. People whose talks I had read and read frequently throughout high school and hard times in college. It was meaningful for me to make my case to them and prayerfully ask them to let women pray.

I initially didn’t want to do it, because I thought it brought an element of triviality to legitimate pain and hurt that many Mormons and Mormon Feminists feel every Sunday. But, after seeing the backlash on the Facebook event page I decided to participate not only to stand in solidarity with other Mormon Feminists but also to demonstrate to anyone in my own ward who may have had similar feelings as those who were actively attacking the event that there are Mormon Feminists everywhere, and that we are normal, faithful Latter-day Saints.

The first respondent describes conflicting feelings and then a resolution that brings freedom and happiness. The second describes activism as an answer to prayer. The third felt a positive connection with religious leaders as she petitioned them. The fourth felt strength as she stood up for what she believed. These kinds of narratives appear throughout Mormon scripture, conference talks, and literature. It is important to note that these women are not describing their activism in rebellious terms but in faithful terms, as an extension of their religious belief.

LDS Church Policy Changes

In February 2010 the Church issued new General Church Handbooks of Instructions, the codified policy of the Church and its leaders. The new edition explicitly states that women are allowed to give opening and closing prayers in any meeting.[50] Some local congregations had previously applied a rule that only those who held the priesthood could give opening prayers. Eighty-seven percent of those surveyed responded positively to this change and nine percent were unaware of it. Another change to the Handbook was a formal invitation to Relief Society presidents, the women in charge of the local women’s organization, to attend meetings of the Priesthood Executive Committee, previously reserved for men.[51] Eighty-two percent of respondents felt that this was a positive change and 15 percent were unaware of it.

During the October 2012 General Conference, missionary ages were lowered from twenty-one to nineteen for women and from nineteen to eighteen for men. The respondents were surveyed on their feelings about the recent age change. Their responses were overwhelmingly positive (85 percent) regarding the reduction of the missionary age for women. Only 47 percent felt positively about the age reduction for men. With these changes, the LDS Church also created leadership positions for female missionaries.[52]

In March 2013 the LDS Church released a new edition of the scriptures exclusively online.[53] These add context to improve the headings in the Doctrine and Covenants and Official Declarations, which are part of the canon of LDS scripture. The new headings give greater historical context and nuance to issues of Church history, especially polygamy. Forty-seven percent of respondents reported feeling positive about the changes.[54]

In January 2013 the LDS Church released new teaching manuals for the youth, incorporating a new format intended to create more conversation. The Church removed gendered material, but the Young Women manuals still use passive language.[55] Forty five percent of respondents were positive about the changes and another 25 percent were unsure.

Eighty-nine percent of respondents agreed that women’s praying in General Conference was the most positive recent change in the LDS Church. The Church has created the website www.mormonsandgays.org in an attempt to clarify its stance on homosexuality. Of those who responded, 48 percent had positive feelings about the website. The LDS Church has also created the website Revelations in Context (history.lds.org). The official LDS Sunday School curriculum for 2013 focuses on Church history, and the new website adds context and transparency to the historical narratives found in printed manuals. Surprisingly, 68 percent of those surveyed were unaware of the website.

The survey asked respondents how they feel about recent LDS Church changes as a whole. Fifty-four percent of respondents felt positive about the changes, 43 percent have mixed feelings, and only three percent had negative feelings. This is an unexpectedly positive result. Seventy-four percent of respondents felt positive about future changes that they believe the LDS Church will make regarding gender inclusiveness. However, a large number of respondents was unaware of recent changes, perhaps showing that the LDS Church does not publicize changes effectively or does not want to be perceived as caving to social pressure.

The respondents were asked what they would like to see in the Church. They reported the same concerns raised in the Issues of Mormon Feminism section above and wanted changes related to those issues. When asked which event of the Mormon Digital Awakening was most meaningful, the respondents cited Let Women Pray and Wear Pants to Church Day with a few references to LDS Church policy changes. The only meaningful policy change identified was the lowering of the missionary age for men and women. Policy changes in the LDS Church require the consensus of its two top governing bodies, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, a total of 15 individuals.[56] The difficulty in achieving consensus perpetuates the conservative nature and slow pace of change in the LDS Church. Mormon feminists and outsiders may perceive the rate of change as being to be too slow,[57] but the LDS Church is changing and appears to be moving in a more moderate direction.

Conclusion

In December 2012, Jezebel ran an article by Katie J. M. Baker titled “Mormon Women are ‘Admired’ But Still Not Equal.”[58] Baker asks, “So how can self-described feminists also be Mormon?” The problem with this question is that it makes several assumptions and lacks nuance, ignoring the great diversity present in Mormonism and feminism and the role of the internet. Perhaps Baker is suggesting that Mormon women, who participate in a rigid patriarchal system, do not have agency, a notion refuted by Hoyt in her chapter on the subject.[59] The question also shows a lack of familiarity with the doctrines and history of Mormonism, which contain many examples of feminism in action and illustrate that there is plenty of room for feminism in Mormon theology. It ignores the fact that many men and women are living out answers to this question and that their numbers appear to be growing.

This study challenges typical views of Mormon feminists and shows them to be believing and active in their local Church communities. Mormon feminists are caught in a difficult situation. Orthodox Mormons are telling them that their position is not authentic and mainstream feminists are telling them that their position is not valid. Mormon feminists are not a problem to be solved but a solution to a problem that is being addressed too slowly. Numerous reports indicate that people are leaving the LDS Church in increasing numbers,[60] and evidence suggests that gender issues play a role.[61] Structures and attitudes in the LDS Church mainly serve orthodox believers. Mormons are encountering material online that challenges traditional ideas of LDS history, practice, and culture, causing some to doubt or abandon their faith.

Current Mormon culture emphasizes a black-and-white, all-or nothing approach to belief. When orthodox Mormons encounter challenges to their faith, they may end up leaving as a result of finding a flaw within the teachings or current practices of the LDS Church. Mormon feminists are used to living with questions of faith and Church practice, have experience in navigating this territory, and tolerate a diversity of belief. They have the tools to help others who are experiencing these tensions and feelings of ambivalence and are able to serve as missionaries for the middle ground of Mormonism.

When organizations are new, they are quite open and engage in building bridges and welcoming outsiders.[62] As time goes by, organizations fall into an in-group/out-group bonded structure, which is often necessary for survival. They need to begin building bridges again as they mature. Unfortunately, organizations often create systems that slow the bridging process.[63] Without bridging, they become brittle and bureaucratic.[64] The solution lies in adaptation. Groups of ordinary people are adept at restructuring well-established paradigms, creating diversity, and fostering dialogue within their communities.[65] Mormon feminists fulfill these roles by addressing issues of belief and patriarchy that are taboo in orthodox Mormon circles. This study shows that Mormon feminists are well-positioned to assist the LDS Church in ministering to both orthodox and unorthodox members.

[1] Some other groups also refer to themselves as Mormons, but this paper will use the term only to refer to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or those closely associated with the Church and its members.

[2] Deseret News, Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013).

[3] Bruce A. Chadwick and H. Dean Garrett, “Women’s Religiosity and Employment: The LDS Experience,” in Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and its Members, edited by James T. Duke (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 401–24; Amy Hoyt, “Beyond the Victim/Empowerment Paradigm: The Gendered Cosmology of Mormon Women,” Feminist Theology 16, no.1 (2007): 89–100.

[4] Jan Shipps, Sojourner in the Promised Land: Forty Years among the Mormons (Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2000); Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007).

[5] Jennifer Huss Basquiat, “Reproducing Patriarchy and Erasing Feminism: The Selective Construction of History within the Mormon Community,” in Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 17, no. 2 (2001): 5–37; Elouise Bell, “The Implications of Feminism for BYU,” in BYU Studies 16, no. 4 (1976): 527–39; Karen Dodwell, “Marketing and Teaching a Women’s Literature Course to Culturally Conservative Students,” in Feminist Teacher 14, no. 3 (2003): 234–47; Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Mormonism and Feminism?” in Wilson Quarterly 15, no. 2 (1991): 30–32; Ulrich, Well-Behaved Women; Maxine Hanks, Women and Authority: Re-emerging Mormon Feminism (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1992).

[6] Lori G. Beaman, “Molly Mormons, Mormon Feminists and Moderates: Religious Diversity and the Latter Day Saints Church,” in Sociology of Religion 62, no. 1 (2001): 65–86.

[7] Boyd K. Packer, Talk to the All-Church Coordinating Council (May 18, 1993), www.lds-mormon.com/face.shtml (accessed August 30, 2013).

[8] Claudia Lauper Bushman and Caroline Kline, eds., Mormon Women Have Their Say: Essays from the Claremont Oral History Collection (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2013); Neylan McBaine and Silvia H. Allred, Sisters Abroad: Interviews from The Mormon Women Project (Englewood, CO: Patheos Press, 2013).

[9] Jessica Finnigan and Nancy Ross, “‘I’m a Mormon Feminist’: How Social Media Revitalized and Enlarged a Movement,” in International Journal of Research on Religion 9 (2013): art. 12.

[10] Dodwell, “Marketing and Teaching.”

[11] Finnigan and Ross, “‘I’m a Mormon Feminist.’”

[12] Ibid.

[13] Basquiat, “Reproducing Patriarchy”; Bell, “Implications of Feminism”; Dodwell, “Marketing and Teaching”; Stack, “Mormonism and Feminism?”; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Border Crossings,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27, no. 2 (2003): 1–7.

[14] Hoyt, “Beyond the Victim/Empowerment Paradigm.”

[15] Laura Vance, “Evolution of Ideas for Women in Mormon Periodicals, 1897–1999,” in Sociology of Religion 63, no. 1 (2002): 91–112.

[16] John Mihelich and Debbie Storrs, “Higher Education and the Negotiated Process of Hegemony: Embedded Resistance among Mormon Women,” in Gender and Society 17, no. 3 (2003): 404–22.

[17] Ray M. Merrill, Joseph L. Lyon, and William J. Jensen, “Lack of a Secularizing Influence of Education on Religious Activity and Parity among Mormons,” in Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42, no. 1 (2003): 113–24.

[18] Rosemary Avance, “Worthy ‘Gods’ and ‘goddesses’: The Meaning of Modesty in the Normalization of Latter-day Saint Gender Roles,” in Journal of Religion & Society 12 (2010), http://moses.creighton.edu/jrs/toc/2010.html.

[19] Lynn Matthews Anderson, “Toward a Feminist Interpretation of Latter Day Scripture,” in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27, no. 2 (1994): 85–204.

[20] Lynn Matthews Anderson, “Issues in Contemporary Mormon Feminism,” in Mormon Women’s Forum (Summer 1995).

[21] Neil J. Young, “‘The ERA is a Moral Issue’: The Mormon Church, LDS Women, and the Defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment,” in American Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2007): 623–44.

[22] Martha Sonntag Bradley, Pedestals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority, and Equal Rights (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2005).

[23] Laura Vance, “Review Essay: Recent Studies of Mormon Women,” in Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 10.4 (2007): 113–27.

[24] Chadwick and Garrett, “Women’s Religiosity and Employment.”

[25] Bruce Chadwick, Brent L. Top, and Richard J. McClendon, The Shield of Faith: The Power of Religion in the Lives of LDS Youth and Young Adults (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010).

[26] Beaman, “Molly Mormons.”

[27] McBaine and Allred, Sisters Abroad.

[28] Bushman and Kline, Mormon Women Have Their Say.

[29] Hanks, Women and Authority.

[30] Beaman, “Molly Mormons.”

[31] Tim B. Heaton, “Demographics of the Contemporary Mormon Family,” in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 25 (1992): 19–34; Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1st ed. (New York: Macmillan Company, 1992).

[32] Beaman, “Molly Mormons”; Dodwell, “Marketing and Teaching.”

[33] Pew Research Center, Mormons in America: Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society (D.C.: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2012), www.pewforum.org/2012/01/12/mormons-in-america methodology.

[34] Michael Lipka, What Surveys Say about Worship Attendance—and Why Some Stay Home (Pew Research Center, 2013), http://www.pewresearch.org/ fact-tank/2013/09/13/what-surveys-say-about-worship-attendance-and-why some-stay-home/ (accessed May 20, 2014).

[35] Chadwick and Garrett, “Women’s Religiosity and Employment.”

[36] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Official Declaration 2, September 30, 1978, http://www.lds.org/scriptures/dc-testament/od/2 (accessed August 30, 2013).

[37] Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell, American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 244.

[38] Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Menstruating Mormons Barred from Temple Proxy Baptisms?” The Salt Lake Tribune, March 5, 2012, http://www.sltrib.com/ sltrib/blogsfaithblog/53650972-180/temple-women-baptisms-mormon.html.csp (accessed July 27, 2013).

[39] Stephanie Lauritzen, “The Dignity of Your Womanhood,” Mormon Child Bride (blog), December 5, 2012, http://mormonchildbride.blogspot. co.uk/2012/12/the-dignity-of-your-womanhood.html (accessed July 23, 2013).

[40] Wear Pants to Church Day, Facebook group, https://www.facebook.com/WearPantsToChurchDay (accessed July 26, 2013).

[41] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Questions and Answers,” in New Era, December 1974, https://www.lds.org/new-era/1974/12/qaquestions-and-answers (accessed August 30, 2013).

[42] Sadie Whitelocks, “Mormon Women Launch ‘Wear Pants to Church Day’ in Backlash over Strict Dress Code,” in Daily Mail Online, December 13, 2012, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2247550/Mormon-women launch-wear-pants-church-day-backlash-strict-dress-code.html (accessed July 26, 2013).

[43] My Gilded Cage, “Dress Code,” My Gilded Cage (blog), May 27, 2007, http://myguildedcage.blogspot.co.uk/2007/05/dress-code.html (accessed July 23, 2013).

[44] Timothy Pratt, “Mormon Women Set Out to Take a Stand, in Pants,” in The New York Times, December 19, 2012, http://www.nytimes. com/2012/12/20/us/19mormon.html (accessed August 30, 2013).

[45] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church Handbook 2: Administering the Church (2010): Section 18.5, http://www.lds.org/handbook/ handbook-2-administering-the-church (accessed August 29, 2013).

[46] Let Women Pray in General Conference, Facebook group, https://www.facebook.com/LetWomenPray (accessed July 26, 2013).

[47] Howard Berkes, “A Woman’s Prayer Makes Mormon History,” NPR.org, April 8, 2013, http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo way/2013/04/08/176604202/a-womans-prayer-makes-mormon-history (accessed July 26, 2013).

[48] Gregory A. Prince, Power from on High: The Development of Mormon Priest hood (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1995).

[49] Taylor Petrey, “Issues in Mormon Feminism,” Peculiar People, January 7, 2013, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/peculiarpeople/2013/01/issues-in mormon-feminism/ (accessed August 8, 2013).

[50] LDS Church, Church Handbook 2: Section 18.2.

[51] Ibid., Section 4.3.

[52] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Church Adjusts Mission Organization to Implement ‘Mission Leadership Council’,” in Mormon Newsroom, April 5, 2013, http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/church adjusts-mission-organization-implement-mission-leadership-council (accessed July 26, 2013).

[53] J. Bonner Ritchie, “The Institutional Church and the Individual,” in Sunstone Magazine (March 1981): 98–112.

[54] Peggy Fletcher Stack, “New Mormon Scriptures Tweak Race, Polygamy References,” The Salt Lake Tribune, March 1, 2013, http://www.sltrib.com/ sltrib/news/55930173-78/church-lds-changes-mormon.html.csp (accessed July 26, 2013).

[55] Brent, “Why Language Matters: A Side-by-Side Look at a Lesson from the New YW/YM Manuals,” in Doves and Serpents, October 12, 2012, http://www.dovesandserpents.org/wp/2012/10/manuals/ (accessed July 26, 2013).

[56] Brad, “Revelation, Consensus, and (Waning?) Patience,” By Common Consent (blog), February 6, 2008, http://bycommonconsent.com/2008/02/06/ revelation-consensus-and-patience/ (accessed August 29, 2013).

[57] Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, reprint edition (London: Penguin, 2007).

[58] Katie J. M. Baker, “Mormon Women are ‘Admired’ but Still Not Equal to Men,” Jezebel, December 3, 2012, http://jezebel.com/5965164/mormon women-are-admired-but-still-not-equal-to-men (accessed August 29, 2013).

[59] Bushman and Kline, Mormon Women Have Their Say.

[60] Chadwick, Top, and McClendon, The Shield of Faith, 33; Rick Phillips and Ryan T. Cragun, Mormons in the United States 1990–2008: Socio-Demographic Trends and Regional Differences (Hartford, Conn.: Trinity College, 2011), http:// commons.trincoll.edu/aris/files/2011/12/Mormons2008.pdf (accessed August 30, 2013); Carrie Sheffield, “Why Mormons Flee their Church,” in USA Today, June 17, 2012, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/ forum/story/2012-06-17/mormon-lds-ex-mormon/55654242/1 (accessed August 30, 2013); Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Gender Gap Widening among Utah Mormons, But Why?” in The Salt Lake Tribune, December 22, 2011, http:// www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/53117548-78/mormons-utah-percent-mormon. html.csp (accessed August 30, 2013).

[61] John P. Dehlin, “Top 5 Myths and Truths about Why Committed Mormons Leave the Church,” Why Mormons Question (website), February 9, 2013, http://www.whymormonsquestion.org/2013/07/21/top-5-myths-and-truths about-why-committed-mormons-leave-the-church/ (accessed August 30, 2013).

[62] Robert Putnam, “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital,” in Journal of Democracy 6, no. 1 (1995): 65–78; Ronald S. Burt, Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992).

[63] Gunnar Lind Haase Svendsen and Gert Tinggaard Svendsen, The Creation and Destruction of Social Capital (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004).

[64] Roger L. M. Dunbar and William H. Starbuck, “Learning to Design Organizations and Learning from Designing Them,” in Organization Science 17 no. 2 (2006): 171–78.

[65] Michel Foucault, Power (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980); Heidi Campbell, When Religion Meets New Media (New York: Routledge, 2010); Putnam and Campbell, American Grace.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue