Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

Mormonism in Latin America: Towards the Twenty-first Century

From the Rio Grande to the Straits of Magellan the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is now taking part in a revolution that is radically transforming Latin America. As a result, the church will also change. This essay explores the current situation of Mormonism in Latin America in the context of this religious upheaval as a means of thinking through issues the church will face there as it moves into the next century.

Revolution in Latin America

During the past thirty years millions of Latin Americans, perhaps 20 percent of the entire continent, have joined new religions.[1] While changing religious affiliation may be common in Anglo-America, it has been rare in Latin America. This is a stunning change in much more than the religious life of Latin America. Catholicism was once central in organizing society there.[2] It connected larger national levels with lowest local levels. It had roots that went deeper than most Anglo-Americans expect in religion.[3] The configuration of Latin American society itself is being transformed. Religious pluralism is now the norm, although many still resist the idea.

This once Catholic stronghold might even become predominantly Protestant. Already, “on any given Sunday more Christians attend Protestant worship than … Roman Catholic churches.”[4] The number of practicing Protestants is greater than the combined total of members of all other kinds of voluntary organizations in politics, culture, and sports.[5] In this panorama of change the most important groups are those originating in Anglo-America. They have flooded the continent with missions over the last century. Of these, the single most significant in numbers of members and rapidity of growth is Pentecostalism, just as is true in other parts of the globe, followed by various Evangelical groups.[6] Seventh Day Adventism, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and of course Mormonism also play an important role.

The Mormon church, despite the enormity of its missionary force— probably greater than that of all Protestant missionaries on the continent combined—does not gain the largest number of converts. It is also relatively unstudied.[7] Nevertheless it is growing in a number of significant social niches and promises to continue doing so in the future.[8] It is building what will become a significant institution in Latin America in that it too connects local events with national, even global, processes.

Mormonism in Latin America

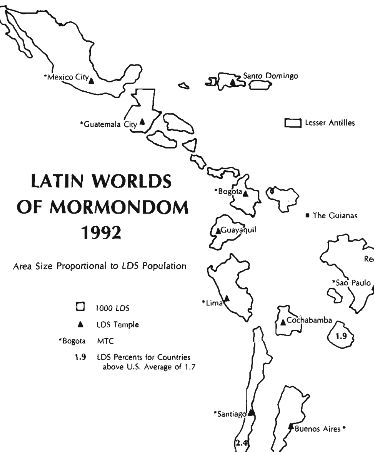

Although Mormon proselyting was initiated in the nineteenth century here, most countries received full-time missionaries only after World War II, and some significantly later.[9] After an initially slow start, church growth jumped sharply in the 1970s and boomed in the 1980s. At times the number of baptisms seemed almost mythological; some returning elders told of baptizing hundreds. By the end of 1993 the church claimed almost 2.75 million members in Latin America, 32 percent of the church total.[10] If growth rates continue, by the end of 1995 there will be some 3.3 million Mormons in this region, and by the end of the century almost 4 million.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1, see PDF below, p. 161]

This development is consistent with the general growth of non-Catholic religions throughout Latin America.[11] It stems from a host of social processes, including problems in the internal structure of Catholicism, military dictatorships, massive urbanization, mass education, rapid population growth, and economic crises. It also depends on the structure of the new religious groups and their national and international connections. Nevertheless, we will need more research than is now available to understand the particulars of what led certain sectors of the population to join the LDS church, while others became Pentecostal, members of Catholic Base Communities, or of Opus Dei, while still others turned to political reform or private voluntary organizations.

Currently most Mormon growth is in Latin America. Despite a popular focus on growth elsewhere, the numbers of new converts outside Latin America remain relatively small. “Between 1987 and 1989 nearly a million new members were added … [Latin America] contain[s] more than 60% of these new members.”[12] Latin America’s share of church membership continues to grow relative to the rest of the church, particularly to the U.S. and Canada. Thus, although people frequently say Mor monism is a “world religion,” in fact it is an American religion; more than 80 percent of its membership is found in the Americas. Only a small number of countries outside this region have significant membership,[13] or much growth in the number of stakes. Between 1988 and 1994, 310 stakes were organized churchwide. Of these only fifty-three, or 17 per cent, were in the U.S.[14] The majority of the rest were in Latin America, where the 2,000th stake was created in Mexico in 1994.[15] At the end of 1993 this region held some 26 percent of LDS stakes, compared with 59 percent for the U.S.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1, see PDF below, p. 163]

This growth pressures the church, straining its capacity to expand while still controlling institutional integrity; yet in many ways Latin America is taking on characteristics of a mature church region. There is an ever-increasing need for new leaders, but there is also a seasoned cadre of Latin American authorities. For example, there are at present eight general authorities from Latin America—not including the Mexican Mormon colonies—and two emeritii. The church developed a corps of regional representatives from the area (now reassigned), and virtually all stake presidents and bishops are Latino, as are an increasing number of mission presidents and missionaries. Twenty years ago virtually none of this pool of leadership existed.

Six temples are currently operating in Latin America (13 percent of the total) and several more have been announced. The church has missionary training facilities in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Guatemala, as well as Area offices in Quito, Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, Guatemala City, and Mexico City. Presiding Bishopric offices function in every country, and the church has a substantial Church Education System, with seminaries and institutes, as well. In addition, in Mexico an LDS history museum was recently established privately, but with official sanction.

An additional measure of maturity indicates what will be a theme of much of the rest of this essay: diversity. One measure of maturity is the to tal number of members per stake, which is relatively small in the core areas of the church. There must be a minimum of active, tithe-paying members for a stake to be established. In mature areas most of the membership will be found in stakes, while in less mature ones substantial numbers will exist in mission districts. Thus in the Utah-Idaho core area of Mormonism, we find between 3,000 and 3,500 members per stake, while in the less mature areas of California, Illinois, and Texas there are between 4,000 and 4,500. In Latin America we find a range, from a low of 4,500 to a high of 7,500 for Peru and Colombia, respectively. The lower figures approximate those for California, Illinois, and Texas, while the higher figures indicate rapid growth (as in Ecuador and Bolivia) and/or high rates of inactivity.[16]

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 2 and 3, see PDF below, pp. 164–165]

At the moment these data suggest that some areas of Latin America show institutional maturity, while others do not. They suggest that further research should explore the relative institutional maturity of Mor monism in different regions and countries if we are to gain a comparative understanding of Mormon growth in Latin America. Although one hears that activity rates are low there, these figures challenge that report some what. In Peru, for example, we find a country undergoing high growth and yet displaying a profile of stake sizes similar to that of California.[17] Relatively small stakes must have reasonable activity rates, with a certain number of people willing to pay tithing and donate their time.

Uneven Distribution of Growth

Despite its growth in Latin America, Mormonism has not attracted converts evenly across regions or countries. Just as certain individuals and families are particularly attracted to this religion, so too are certain regions and countries. In fact, Mormon membership is concentrated in specific key areas. This bespeaks a relationship among the structure of the church, its allocation of resources, and the nature of each local society. Furthermore, it provides the LDS church with its peculiar dynamics in the continent.

In absolute numbers more than 80 percent of Mormons in Latin America congregate in just seven of the twenty countries that form the region: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru.[18] Two of these, Mexico and Brazil, are giant countries with more than 80 million inhabitants each. Mexico, with 688,000 members, has a third more than Brazil’s 474,000, even though its population is about half as large. Two others are relatively tiny, Chile and Ecuador, with fewer than 15 million inhabitants each. Yet Chile, with only some 13.5 million inhabitants, has 345,000 Mormons. This is where Mormonism has arguably had its greatest success in Latin America. Chile’s population forms 3 percent of the Latin American total, and it holds only 4 percent of the continental land mass, but it claims 13 percent of the total Mormon membership for Latin America. Yet Mormon proselyting began in Mexico in 1876, eighty years before it began in Chile. The relatively large country of Colombia, with a population of more than 34 million, has only some 96,000 members. Proselyting did begin relatively late there, in 1966, some ten years after Chile. Also the country is known for having the strongest formal Catholic presence in the region and some of the lowest numbers of Protestants, as well.[19]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 4, see PDF below, p. 167]

The relative percentages that Latter-day Saints form in the various national populations also vary widely. At its high end, with an amazing 2.6 percent, is Chile. Outside of Oceania, this is the highest relative Mormon percentage for any country. It places Chile in the company of such U.S. states as Colorado and California, which are just outside the traditional Mormon geographic core. Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua bring up the rear. This variation suggests, once again, the importance of local social structure and history and the critical need to do research on the growth and development of the various national Mormonisms. For example, Nicaragua once had a thriving LDS population, but after the Sandinista revolution of 1979 it disappeared almost entirely, because of the U.S. political relationship the Sandinistas attributed to Mormons. In Chile, on the other hand, evidence suggests that Mormon ism found favor with the Pinochet dictatorship and might even have re ceived quasi-official sanction, as part of a so-called “Protestant card” played to stop the growth of leftist Catholicism.[20]

Venezuela is one of the most secular Latin American societies—i.e., one with the least formal influence of Catholicism. This factor explains the situation of other religions there and might also explain the low per centage of Mormons. Yet another country known for its extreme secular ity, Uruguay, has one of the highest relative percentages of Mormons at almost 2 percent. However, in Uruguay this growth occurred during an earlier period, for it currently has a very low Mormon growth rate, while Venezuela is experiencing substantial growth. Thus not only must we take national structures into account, we must also locate them in time to see how historical configurations have militated for or against Mormon growth. Each of these factors gives the resulting national Mormonism a somewhat different character and provides limits on its continued expansion.

One final example: the three Andean countries which stem from the old Inca Empire—Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru—share similar social structures but have substantial historical differences. Nevertheless, they have at the moment almost identical percentages of LDS membership, around 1 percent. Growth has recently declined in Bolivia but remains high in the others. In Bolivia two U.S. missionaries were assassinated, and a guerrilla group dedicated substantial effort to eradicating Mormonism, without success. In Peru, despite the assassination of three missionaries, the Mormon church has remained relatively uninvolved in Peru’s guerrilla war, unlike the Pentecostals and Adventists.[21] The growth of Mormonism there undoubtedly is attributable somewhat to the social and economic chaos the country has experienced. Furthermore, in all three countries Mormonism takes diverse paths in its relationship to the large indigenous populations and to the local politics of Indian identity in each country.

Another country, Guatemala, also has a relatively high LDS percentage, higher than that of the equally indigenous Andean region, at 1.4 per cent. This country has also experienced a brutal civil war and social chaos. For reasons of the particular way in which religion fits into the struggles and into local political economies, it has probably the highest percentage of non-Catholics in Latin America. Estimates range as high as 50 percent. Mormonism undoubtedly bears some relationship to this general pattern.

Regional Distribution

Mormonism is strongly concentrated in Latin America’s cities. It is not a rural religion, with a few exceptions.[22] Its efforts to move into rural areas and work with rural populations, particularly the indigenous ones of Mexico, Central America, and the Andes, have been relatively unsuccessful. In part this is because the social structure of the church, with its emphasis on residence-based congregations, is designed more for towns and cities than for rural social life.

Not only is Mormonism biased in favor of cities and urban skills, it arrived in Latin America at a time of unprecedented urban growth. Since World War II Latin America has shifted from predominantly rural to pre dominantly urban in the distribution of its population. The urban growth has been phenomenal and has meant that the problems of urban planning and human need have overwhelmed the cities of the region. Mor monism and many other new religions have found fertile soil here for growth.

Many Latin American countries have further suffered from what many call hypercephaly, the growth of a large city that dominates the nation, such as Mexico City in Mexico, Buenos Aires in Argentina, and Lima in Peru. The relationship of Mormon growth to hypercephaly is unclear. Santiago, for example, contains slightly more stakes than its LDS share of the national population would indicate. In Mexico it is different. There is a concentration of Mormons in the city, but it is smaller than the size of the city would seem to warrant. In part this is explained by the growth of Mormonism in regional cities near the valley of Mexico, which gives it a peculiar character there, and very strong growth in the cities of the north, where the church is overrepresented. There it contains almost 45 percent of the total stakes for Mexico. The north also has almost 50 percent of total membership for the country, while Mormon presence in the indigenous regions of southern Mexico is weak. Undoubtedly the strength in the north has something to do with the region’s shifting social and economic relationship with the United States, but what, precisely, re quires detailed and cautious research?

Every country shows LDS distributions that do not correspond to those of the general population, but which indicate that other dynamics are at work to produce the various concentrations of Mormons. Another example: in Peru we find a large concentration of stakes, 44 percent of the total, in metropolitan Lima. This is greater than its share of the national population. We also find 73 percent of stakes along the coast, while the highlands, the traditional population center of Peru, claims a scant 18 percent. This reflects the recent massive population movement from the highlands to the coast because of economic problems and violent civil conflicts in the highlands. I imagine that among this immigrant population the church has made great gains, but there remains the critical question of which specific segments of that population have been drawn to Mormonism and why.

There is another anomaly in Peru that requires explanation. Why are 20 percent of stakes found on the north coast, while the south, including the inland city of Arequipa (the second city of Peru), claims a mere 16 percent? Members from the north coast have further claimed, somehow, a niche of BYU alumni; its student population, when I worked there, was almost entirely composed of people from the city of Trujillo. It would be interesting to know what social factors led to this situation.

Mormonism is also concentrated in particular neighborhoods. For ex ample, in Santiago, Chile, the greatest number of stakes is found in those neighborhoods which are expanding and which comprise some of the poorest in the city. This creates a very uneven distribution, with stakes congregating along a north /south corridor and being relatively sparse in the east and west.[23] Similarly, in La Paz, Bolivia, there is a concentration of stakes in the upper parts of the city, those areas which are more indigenous and also poorer,[24] but the relationship to indigenous issues is ambiguous at best.[25]

While Mormonism may find many converts in the informal neighborhoods and shantytowns that ring Latin America’s cities, its institutional growth carries a distinctive middle-class character.[26] It is likely that Pentecostalism better typifies the dynamics of the shantytowns and working-class neighborhoods of the continent, as David Martin argues.[27] On the one hand, he claims that Pentecostalism relates to the social structures and values more typical of the bourgeois or middle-class societies of the developed world. On the other hand, he writes that it is primarily the poor, those who are not able yet to take on bourgeois culture, who are be coming Pentecostal. The same might be true for Mormons, although it seems to me that Mormonism is much more successful in its relationship with bourgeois society, despite the correlation between Mormon presence and poor neighborhoods.

Social Position of Leaders

A substantiation of the essentially middle-class character of Mor monism can be seen in the employment of its leaders. As we shall see, not only do most leaders in stake presidencies and higher fill middle-class occupations, but the majority comes from sectors with management skills, sectors relatively young and growing rapidly, as the Latin Ameri can economy changes.[28]

Part of the challenge Mormonism has faced has been the need to obtain leaders who fit the requirements of our bureaucratized church. We have had to convert people and train them quickly in the requirements of Mormon leadership. Besides whatever spiritual qualities might be required, Mormonism requires a commitment of a significant portion of one’s time to church service and a sufficient education in the culture of management to be able to perform according to church practices. Thus we should not be surprised that church leadership tends to be drawn from relatively narrow social circles. Mormon leadership shows an affinity with certain segments of the society and is colored by them. Virtually none of the leaders comes from the laboring classes that make up the majority of Latin America’s workforce. Even in those stakes in heavily working-class areas, there appears to be a preference for leaders from the management sectors. One finds a few stake presidents and counselors who are skilled or unskilled laborers, but they are exceptions that high light the general trend.

Another critical group from which the church recruits leaders is the salaried employees either of the Church Educational System or of the Presiding Bishopric’s Office. This is truer the higher the leadership level, and is especially true of regional representatives, mission presidents, and Latin American general authorities. This means that church employment is important for future high leadership. We have professional full-time church leaders augmented by another cadre from the private business world. A problem with salaried church employees in a lay leadership is that they sometimes elicit envidia, or jealous envy, since some leaders will seem to be rewarded arbitrarily with church jobs while others will not. Church employees are already suspected in some areas of being a kind of church “nobility,” leading to some tension, anger, or even hatred.[29]

Nevertheless the church will need to expand its bureaucracy greatly in Latin America to cope with the growth there; and for the foreseeable future church employees are just about the only large group of Latin America members who can afford to leave their work for three years to serve as mission presidents. Yet this undermines the tradition of a lay church, suggesting for Latin Americans the image of a paid clergy, separate from ordinary church leaders, who occupy a privileged position. In addition, salaried leaders occupy a career track leading to the highest ranks of church leadership, including the general authorities. This situation carries a potential for serious conflict in the Latin American church.

Whether or not by design, certain socioeconomic sectors symbolically represent the church as its leadership. Though the majority of members might come from less affluent sectors, the character of the institution is symbolically represented by those from the management sector, including salaried church employment. This sector was virtually nonexistent in Latin America fifty years ago but has expanded massively during the same period the church has grown there. Since it promises to continue expanding as Latin America develops economically, the church is in a favorable niche for further growth, despite the simultaneous potential for class conflict.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 5, see PDF below, p. 173]

On the other hand, there is also a potential for integrating lower-class members into a corporate structure stretching from the top of society to the bottom. Such corporate structures have been a familiar mainstay of Latin American social organization. In this respect the LDS church will likely present a contrast with many of the more numerous Pentecostal churches, since they tend to integrate horizontally rather than vertically. In its vertical emphasis and authority structure, Mormonism is not unlike the right-wing Catholic movement Opus Dei which is also spreading in Latin America among particular social sectors.[30] A study comparing Mormon growth and membership characteristics with those of Opus Dei would be interesting.

Toward the Twenty-first Century

From this limited discussion of the LDS church structure in Latin America, we can intuit a number of themes that will emerge in the twenty-first century.

First, sometime between 2010 and 2015, if growth continues at cur rent rates, Latin American Mormons will constitute a majority of the church, leading perhaps to a “latinization” of the entire church as increasing numbers of general authorities come from that region. We could even see a Latin American president by the end of the century. This would be a change as momentous as the relatively recent election of a non-Italian Pope in Rome. Cultural and social concerns from Latin America will then increasingly become the background from which church manuals, general authority talks, and policies are formulated. This might lead to some tension between Anglo- and Latino-Mormons over issues of cultural hegemony expressed in gospel concerns.[31] Given the diversity in Latin America, we can expect substantial discussion about how the varieties of Latin American culture and social organization will be manifested in church programs. Will church leaders attempt in this process to distinguish Wasatch Front culture from gospel culture? Or will Anglo-Ameri can culture be sacralized as part of the gospel, somewhat as Arabic culture as been in Islam?

Second, the church will increasingly be caught up in the social and political dynamics of this region. These include issues of mass poverty, nationalism versus internationalism, conflicts over capitalism, education, employment, gender and sexual issues, and how morality and religiosity are applied to those issues. Already Pentecostals and Evangelicals are being drawn into politics, despite their strong resistance. One hears of de sires by Latin LDS leaders to form Mormon-based political parties or groups to influence various national discussions.[32] This political pressure is but one of many points where Mormonism will be drawn into Latin American social concerns, even if it is manifested only in resistance.

Third, we can expect the increasing growth of various national Mormonisms. Inevitably, the national churches will respond to national issues, although there might be, of course, tension with central church authority. In subtle ways Mormonism blends with its new milieux creating Mormonisms that are not all identical. Even if they continue to use the same ritual and symbolic forms, the contextual meanings given them are different. Already this is reported in the increasing literature on the church in that region.[33] Furthermore, we might find the development of a “popular” (folk) Mormonism different from that of the formal church. In this usage “popular” stems from the social science literature in French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish in reference to the religion of the “people” rather than that of elites and institutions. A rich literature discusses this phenomenon in Latin American Catholicism, and it appears also as an issue for Protestantism.[34] More importantly, it is the numerically dominant form of religion with deep psychological roots in Latin America. As a result, Mormonism will feel increasing pressure to accommodate or actively resist it.

Finally, the church’s growth is constrained by the social niches from which it recruits and the elective affinities between them and the institutional church. These niches both limit and enhance the church’s potential for growth; but at some point they might bring the church into conflict with the broader Latin American society. One example, above mentioned, comes from the church’s penchant for taking leaders from among church employees and the managerial class. Given the recent expansion of the latter class in Latin America, it has provided a fertile basis, symbolically and materially, for church growth. However, it can just as easily serve as a symbol of exploitation. Much here depends on how the social constituency of the church and its leaders is invoked in local political struggles, as happened in Bolivia and Chile with the terrorist strikes against the church.

Internally too the church must deal with the perception that it is producing an almost professional caste of leaders. This inevitably will enter into tension with the Mormon norm of voluntary service and lay leadership. The problem exists in a tenuous space between pragmatism and the Latin American understanding of social position as a kind of prebend for the benefit of oneself. Already, given popular complaints, this is a problem and will increase in intensity.[35] It desperately needs study.

The Drama of Mormonism

This essay has explored Mormon reality in Latin America as part of a complex of changes revolutionizing the continent. We hope to extend a filament of understanding to look to the future. Yet we still do not know much. Little research has been performed into the nature of the rapidly growing Mormon church there. Only fools, prophets, and futurologists make firm claims about the future. Here I say merely that we have front row seats to watch a first-class drama unfold, one which will transform both Latin America and Mormonism. Yet we know only its title and a vague abstract of its possible plot. The curtain is drawn, the revolution has begun.

[1] David Martin, Tongues of Fire: The Explosion of Protestantism in Latin America (Oxford, Eng.: Blackwell, 1990); and David Stoll, Is Latin America Turning Protestant? The Politics of Evangelical Growth (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

[2] As an entry to the voluminous literature on Catholicism in Latin America, see Daniel H. Levine, Popular Voices in Latin American Catholicism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), and Penny Lernoux, The People of God: The Struggle for World Catholicism (New York: Viking Press, 1989).

[3] “Anglo America” refers to English-speaking countries, while “Latin America” refers to Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking countries in the Western Hemisphere.

[4] Guillermo Cook, The Changing Face of the Church in Latin America (Maryknoll, NY: Or bis Press, 1994), ix-x.

[5] Phillip Barryman, “The Coming Age of Evangelical Protestantism,” in NACLA Report on the Americas 6 (May/June 1994): 6-10.

[6] Martin.

[7] See bibliography on Mormonism in Latin America compiled by Mark Grover, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[8] Martin, 207-10.

[9] Rodolfo Acevedo, Los Mormones en Chile (Santiago: Impresos Cumorah, 1990), Nadia Fernanda Amorim de Maia, Os Mormons en Alagoas: religiao e relacoes raciais (Sao Paulo: FFLH/USP-CER, 1986), F. LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), and Frederick G. Williams and Frederick S. Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree (Ful lerton, CA: Etcetera Etcetera Graphics, 1987).

[10] This figure is based on Deseret News 1995-1996 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: De seret News, 1994).

[11] Martin; Stoll. See also William Mitchell, Peasants on the Edge (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991).

[12] Tim B. Heaton, “Vital Statistics,” in Daniel Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1994), 4:1521.

[13] Australia and New Zealand, Great Britain, Japan, and the Philippines.

[14] Church News, 17 Dec. 1994,7.

[15] Ibid., 3.

[16] I divided the total membership by the number of stakes as reported in the Deseret News 1995-1996 Church Almanac to obtain these figures.

[17] A caveat: If for some reason stakes in areas of Latin America are substantially truncated in organizational requirements, this may not follow. In that case Peru and California, for example, would not be comparable.

[18] Unless cited otherwise, all figures are based on Deseret News 1995-1996 Church Alma-

[19] Stoll; Levine.

[20] Ethnographic evidence gathered in interviews I conducted in Chile, 1991 and 1992.

[21] Juan Ossio, Violencia estructural en el Peru; antropologia (Lima: Asociacion Peruana de Estudios e Investigacion para la Paz, 1990).

[22] For example, Huacuyo, Bolivia, reported in David Knowlton, “Protestantism and Social Change in a Rural Aymara Community,” M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1982. See also Martin, 96, whose contrasting viewpoint is based on a literature which over emphasizes rural Mormonism, and see David L. Clawson, “Religious Allegiance and Eco nomic Development in Rural Latin America,” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 26 (1984): 499-524.

[23] David Knowlton, “Violence and Mormonism in the Crucible of Social Change: The Cases of Bolivia and Chile,” read at International Conference on New Religions, Recife, Brazil, May 1994.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Julio Cordova Villazon, “Los evangelicos, entre la protesta y la compensadon mi norias religiosas y sectores urbano-populares: el caso de El Alto,” thesis of Licenciatura, Uni versity Mayor de San Andres, La Paz, Bolivia, 1990.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] The data for this assertion come from a classification of occupations listed for mem bers of stake presidencies, mission presidencies, regional representatives, and general authorities as published in the Church News for 1993 and 1994.

[29] This issue came up periodically during my ethnographic interviews in various countries. See n35.

[30] Michael Walsh, Opus Dei (San Francisco: Harper, 1992).

[31] This, in fact, was important in the “Third Convention” conflict in Mexico early in this century (see Tullis).

[32] Ethnographic interviews with Latin church officials.

[33] See, for example, Mark L Grover, “Relief Society and Church Welfare: The Brazilian Experience,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27 (Winter 1994): 29-40; as well as Thomas Murphy’s essay on Guatemala in this issue.

[34] See, for example, Jose Luis Gonzalez and Teresa Maria van Ronzelen, Religiosidad Popular en el Peru (Lima, Peru: Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, 1983), Lynn Stephen and James Dow, Class, Politics and Popular Religion in Mexico and Central America (Washington, D.C.: Society for Latin American Anthropology, 1990), or Thomas A. Kselman, “Ambivalence and Assumption in the Concept of Popular Religion,” in Daniel H. Levine, ed., Religion and Political Conflict in Latin America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

[35] During my stints of ethnographic fieldwork on religious questions, 1979,1985,1987, 1988,1989,1991,1992, and 1994 in Bolivia, 1990 in Argentina, and 1991 and 1992 in Chile, as well as from occasional ethnographic interactions in Peru, this issue continually came up in interviews of varying natures.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue