Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

Mormonism in the Twenty-first Century: Marketing for Miracles

In recent years social scientists have found it theoretically useful to understand church growth or decline in the context of a “religious economy.”[1] In this conceptualization each society has a “religion industry” in the same way that it has a food industry or a clothing industry. Each de nomination or church is a “firm” with a certain line of “products” competing with those of other religious “firms” to meet the needs or tastes of as large a segment of the “market” as possible. Some products are mundane in nature, such as social and/or economic support, community feeling, entertainment, intellectual stimulation, or even useful business contacts. However, a church which depends for its survival and growth mainly on such mundane products will find itself competing with many firms in the non-religious industrial sectors which are in stronger competitive positions, so it will probably not prosper. Religions are more likely to prosper to the extent that they deal mostly in the unique “products” of the religion industry, namely other-worldly “products,” like heavenly promises, rewards, meaning systems, relationships with deity and with departed loved ones, and so on.[2]

As in the commercial world, religious monopolies or other “restraints of trade” tend to depress entrepreneurship in the market. Thus in societies that have only state churches, those responsible for delivering goods and services (i.e., the clergy) tend to become complacent, formal, distant, and bureaucratic in dealing with the laity who are their “customers.” The latter, in turn, come increasingly to participate in church activities in only a perfunctory manner, if not a cynical one. To the extent that religious institutions provide important rites of passage (like weddings and funerals), or useful social services (like schools or hospitals), people will periodically (but unenthusiastically) seek their services in the same way that they seek food, clothing, or shelter from other state monopolies. Otherwise, they will have little to do with churches, especially on Sundays, when there are other, more inspiring diversions from the work week.

To the extent that state controls on religion are lifted (as in western Europe a generation ago and in the former Soviet bloc more recently), new religious enterprises arise to meet the “pent-up need” for trade in the new “products.” To be sure, not everyone will suddenly seek these products, for the cynicism of centuries dies hard; yet the market for new religious products (to the extent that it remains unfettered by state intervention) will gradually expand, and even the old state religions might experience some resurgence. Such, at least, has been the experience historically in the United States and more recently in Europe. From the viewpoint of the religious establishment, it might seem paradoxical that religion seems to thrive to the extent that it is free of state sponsorship; but there is no paradox for modern economists, who have always known that the more competition there is among individual enterprises, the more the options for the variety of potential customers, and therefore the greater the market for the entire industry.

When viewed from the individual perspective, this well-known market process means simply that people seeking other-worldly products will have many choices, not just the tedious traditional ones offered by monopoly religions. To be sure, not everyone in a given society is in the market for other-worldly products, but that market is much larger than one might think from the rampant secular cynicism that we associate with advanced industrial countries; it might even comprise a majority of the population in many countries. Whatever this market potential, the new religions offer an enormous range of products, from the inspiring music and liturgy of high mass to the highly emotional, participatory frenzy of pentecostal encounters with the Spirit, and everything in between. In this array of programs for making connections with deity, or with other supernatural forces, different varieties will appeal to different kinds of people (that is, to different “market segments”) for different rea sons.[3]

Each variety too will carry a different cost for its potential customers, and each customer can be expected to make a cost-benefit assessment, at least implicitly, before adopting a new product. The “cost” side of this assessment consists of what one has to sacrifice (including respectability) to embrace a new religion (product). The “benefit” side typically is of two kinds: (a) the social, emotional, intellectual, or other kinds of gratification received from participation with others in the services and programs of the religious movement or institution; and (b), at least as important, the promises of salvation, beatification, exaltation, or other such blessings in the next life. To be sure, the other-worldly blessings in (b) are all “unfalsifiable,” in the jargon of science: they cannot be proven empirically to exist and thus must be accepted on faith.

Of course, the same is true of other “future promises” in life, such as the prospect that the next hand at cards, roll of the dice, or turn of the wheel in Monte Carlo will be the “lucky” one; or that the next business deal (despite high risks) will finally be the big one; or even that the next wife (or husband) will be a big improvement over the one divorced last year. There is thus nothing inherently more irrational about acting on faith in the next life than in acting on faith in the next wife! The prospect of big gains often requires taking big risks on faith or hope, and costly sacrifices “up front” (here and now) represent but one kind of risk.

Whether the prospective benefits (gains) are mainly of the worldly or the other-worldly kind, the “consumer” (convert, member) of the religion must believe that the potential gains justify the cost and risk. One consideration, of course, is the nature of the other-worldly promises themselves: A promise of eternal family bonds and eventual godhood, for example, might be more appealing to consumers than certain other conceptions of the next life. Another important consideration is the cost itself: It might be either too high or too low, depending on the “social capital” that consumers must sacrifice versus that which they stand to gain through the conversion process. That is why most converts to new religions tend to be young with relatively few “stakes” yet invested in the conventional social and economic institutions of their societies; or they might be “marginal” in other senses, such as having already experimented with unconventional religions or lifestyles. Youthful and marginal members of every society have much “less to lose” by “buying into” a new religion than do other members who have invested more of their lives and identities in conventional institutions. In that sense certain kinds of people in every society are socially more “available” than others for recruitment as “consumers” to a new religion with the right kind of appeal. It is such socially available potential consumers that constitute the field that is “white and ready to harvest.”[4]

Yet consumers’ cost-benefit assessments involve more than the ap peal of the “product” and the estimate of what they stand to gain or lose by “buying into” the new religion. The cost of buying into a new religion can obviously be too high, but it can also be too low. If a religious community makes but few and weak demands on its members for access to its products, many members will assume that the products themselves are not valuable. The cost must seem commensurate with the greatness of present and future gains. That is why, as recent research has shown, religious movements and communities that enjoy the greatest growth tend to be those which make the most strenuous demands on their members

(not vice-versa). Another function of “high cost” religious products is that they tend to discourage “free riders”—those members (consumers) or future members who might otherwise enjoy access to these highly desirable products without paying the cost. Thus, if many demanding or “high cost” religions tend to be relatively small in membership, at least the average levels of commitment and sacrifice for the religious community are relatively high and mutually reinforcing for individual members.[5]

One of the factors determining the “cost” of conversion and member ship in a new religion is the degree of tension between the culture of the religion and that of the surrounding society. If the religion and its “products” consist of beliefs, rituals, and behavior strongly at odds with the surrounding culture, the religion will be stigmatized and persecuted (formally and informally) by the rest of society. The degree of cultural tension between the two will thus greatly limit the “market share” or “market niche” of the religion (perhaps even criminalize it) and will correspondingly increase the “cost” to the individual adherents or consumers. Therefore, as important (and complicated) for LDS church growth as are the demographic factors discussed earlier (by Bennion, Young, and the Shepherds), many of the factors that will determine the future of the church are cultural, economic, and political, rather than only demographic.

The potential for any religious movement or organization to grow depends largely upon its ability to maintain “optimum tension” with the surrounding cultural environment in which it operates. Too much tension brings various forms of persecution and repression, which dissipates the resources of the religion and makes the social (or even economic) cost of membership too high for many individuals to bear. Any religion (or other subcultural movement) that will not make assimilative compromises (as the Mormons finally did after 1890) can expect either a rapid demise, as in the cases of Jonestown and the Rajneeshees, or a slow, lingering de mise like that of the Shakers. On the other hand, if too much assimilation occurs, the tension with the surrounding culture becomes minimal, so that the distinctive mission and benefits of the religion are unclear and lack wide appeal. Unitarians are among those exemplifying the eventual fate of low-tension religions. Thus it is neither maximum nor minimum but optimum tension that provides the best prospect for the future of any religious movement or organization.[6]

Mormonism in the World Market

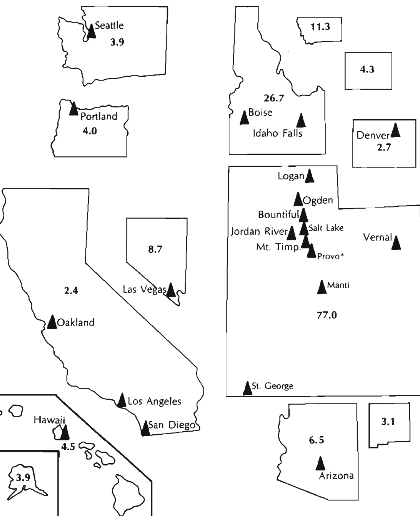

Obviously the church has gotten the “tension factor” about right in its twentieth-century relationships with the host societies in the United States and in many parts of Latin America—at least so far. As we can see from the essays in this collection, however, all is not well in other Zions. As much as we might be entitled to rejoice in the spread of the gospel to so many parts of the earth, the fundamental reality is that we are nowhere near having a “world church.” We can more accurately be considered a “hemisphere church/’ for 85 percent of all Mormons live in the Western Hemisphere. The church has certainly prospered at certain times in other parts of the world, depending on local circumstances. It appears, however, that success has often depended largely on influences more worldly than spiritual, such as the appeal (usually temporary) of Ameri can cultural imports, including religions. I well recall, during my own four-and-one-half-years’ sojourn in Japan in the early 1950s, how our missionary success there rode upon a wave of popular interest in all things American, including the English language, a wave that has long since receded to a ripple, if we are to judge by Numano’s essay herein. The recent rapid growth of the church in the Philippines might well be related to similar (and equally ephemeral) local conditions. Even the ap peal of the Mormon message to those thousands of nineteenth-century British, Scandinavian, and German converts could not easily be separated from the appealing prospects of emigration to America during that era. These were all times and places in which the benefits of Mormon conversion, for many at least, seemed to outweigh the costs of experimenting with things American, including a new religion.[7]

Does this mean that LDS conversion and church growth in the world depend upon the nature and appeal of American cultural and political in fluence? One is tempted to draw parallels between Roman Christianity and American Mormonism: Just as early Christianity did best wherever Roman influence went, so Mormonism seems to do best wherever American influence is felt (especially to the extent that such influence is welcomed). Yet it is obviously not that simple. As Knowlton makes clear (both in his essay here and in earlier ones), American influence is a mixed blessing in Latin America. On the one hand, some of the appeal of the Mormon message seems to lie in its emphasis on traditional American values (family, education, self-discipline, upward mobility); on the other hand, anything American is definitely a liability in those countries with strong leftist and/or anti-colonialist sensitivities. Thus the American connection will probably help the LDS cause in some times and cultures but hurt it in others. Increasing the non-American proportion of the world’s LDS missionary corps would be a wise strategy in this regard, especially if these could serve in Latin American and other countries especially sensitive to the American (and/or C.I.A.) presence.[8]

To return to the main point, though, the crucial factor, however it is affected by American influence, will be the success of the church in achieving and maintaining “optimum tension” with the local culture in each part of the world where we aspire to have a significant presence. Since the variety of cultural settings is almost infinite, the strategies, tac tics, and doctrinal emphases of the church will also have to vary in order to achieve the right kind and degree of tension. This requires a great deal of inspiration and sophistication on the parts of church leaders at the general and local levels. If its operations or teachings seem to generate too much tension in a given locale, the church will not only have public relations and proselyting problems; it will eventually be closed down or expelled, as it was for a time in Ghana and in Indonesia. Even before the church seeks permission to operate legally in a given country, it might be perceived by the government as somehow alien and dangerous and thus be refused entry, as is still the case in China (officially) and in most Islamic countries (for all practical purposes).

The church has already shown strategic skill in dealing with nations that have been reluctant to permit LDS proselyting or organizing operations. The construction of a temple in East Germany, long before the fall of communism there, bespeaks that skill. As often as not, the LDS strategy in China and elsewhere has consisted of cultivating good will through the use of BYU programs, Tabernacle Choir visits, LDS technical and business experts travelling under non-church auspices, and so on. Furthermore, though it is not well known, the church, through various kinds of expert “humanitarian missionaries,” has been funding an enormous program in various countries of medical, agricultural, technical, educational, and social service programs of all kinds. These efforts are in dispensable to the eventual establishment of the church in such countries; for most of them have made clear to all foreign churches that they will not be welcome until they have shown a willingness to help with modern development (sometimes called “nation-building”), which is the top priority in most of those countries today. Although such contributions are undoubtedly rendered by the LDS and other denominations in all sincerity, they might also be considered part of “the cost of doing business” in the missionary enterprise.[9]

Aside from such general strategies, tactics too can be adapted to fit local cultural norms. Missionary street-meetings, once a major tactic in England and America for reaching large numbers of people quickly, do not work so well any more; cultural images of such activities in those countries now make them seem bizarre (partly because other groups now using street gatherings often are disruptive to the cultural mainstream). Besides, in this age of mass communication there are more efficient ways to reach large numbers of people. One wonders if another time-honored missionary tactic, namely “tracting,” might not also have become a cultural liability in many countries. Newton’s essay on the Australian experience suggests that tracting there might actually undermine church prospects; and in many other places (including the U.S.) it is obvious that tracting is now regarded as the last resort for the use of missionary time. Member-missionary collaboration is clearly preferred as a proselyting tactic in many places, although in continental Europe, and perhaps in other cultures, even that might breach a customary wall of privacy which the local people prefer to maintain in matters of religion. Perhaps, as De coo suggests, “cybertracting” (it might be called) will provide an efficient way of reaching people not now accessible through traditional tracting.[10]

Like tracting, home teaching of the American kind is also considered an invasion of privacy in some cultures. Clearly new tactics, both in proselyting and in general church operations, are being called for as the church gains a presence in the myriad cultural settings around the world. The church has obviously made its mistakes and had its setbacks in both strategies and tactics throughout its history in different parts of the world. We are still paying a price for some of those tactics that seem in retrospect to have been ill-advised, such as the experiments in high-pressure, premature baptisms, called “baseball baptisms” in England and elsewhere, or by other names in Australia and Japan (see Newton’s and Numano’s essays). However, time and again the church has also shown flexibility and creativity in tactics and strategies. One example that has created a lot of good will has been the allocation of a few hours of missionary time each week to community service, an arrangement that obviously could be expanded or contracted in response to varied local conditions.

Toward a Parsimonious “Gospel Culture”

Culturally sensitive innovations in strategies and tactics, however, will always prove less difficult than ideological or doctrinal flexibility, which is clearly a crucial element in maintaining optimum cultural tension. The potential for flexibility is curtailed by at least four simplistic ideas about doctrine found among Latter-day Saints: (1) doctrines in the scriptures (and elsewhere) are clearly spelled out and can be understood best through literal interpretation; (2) whatever a church leader says, especially if and while he is a president of the church, is doctrine and can readily be harmonized with whatever other church leaders have said; (3) all doctrine has equal weight or importance with all other doctrine, so that doctrine is doctrine; and (4) there have been no doctrinal changes in the history of the church, for true doctrine has always been the same. To the extent that the Saints or their leaders maintain such an understanding of doctrine, whether in Utah or in other parts of the world, Mormonism will prove difficult to transplant in a variety of cultures, and quite unnecessarily so.

This is not the place for a point-by-point consideration of these four folk maxims, but to some extent the first and third ones are addressed in both Sandberg’s and Bailey’s essays in this collection. The second one was more than adequately refuted by J. Reuben Clark in 1954.[11] The third and fourth ones are refuted by Thomas G. Alexander’s historical study of various doctrines; by the obvious modification and truncation through out this century of the doctrines about plural marriage and millennial ism; and by the recent changes, familiar to all of us, in traditional doctrines about black people.[12] On the other hand, it would be equally simplistic (and disastrous) to hold the view that church doctrines are more or less infinitely adaptable to fit the cultural biases or traditions of any people on earth. The tough questions really are: (1) Which doctrines constitute the absolute, minimal, unchangeable core of the restored gospel, and how can we tell? (2) How much flexibility or latitude can be per mitted in the interpretation of other doctrines to give them salience and authenticity in various other cultures? (3) Which traditional LDS ideas are either not official doctrines or are simply American (or Utah) customs rather than doctrines and can be considered entirely optional from one culture to another?

In this church we must look to our prophets for a definition of the hard, minimal core of absolutely essential doctrine that will unite all Latter-day Saints in the world across all cultures. Clearly the presiding brethren understand this need, for in recent years they have spoken about the need to identify a “gospel culture” which will unite Latter-day Saints across all cultures while remaining free of biases from any one of the world’s cultures.[13] So far, however, there have been few efforts at authoritative articulations of the precise content of this “minimal Mormon ism,” at least for the church membership at large. In 1971 the Church Board of Education outlined the “basic doctrines of the Gospel… essential to developing a religious education curriculum,” a four-page summary of doctrines on the Godhead, humankind, the purpose of earth life, Satan, human agency, the Fall and Atonement, the gospel of Christ, the kingdom of God, judgment, salvation, and exaltation. Given the specified purpose for this document, and the twenty-five-year interim, it is not clear how authoritative this doctrinal summary is for the worldwide church today. It is certainly not a parsimonious document, and some of its doctrinal declarations seem gratuitous and problematic if the church is to maximize its cultural adaptability.[14]

A more succinct document, and presumably a more authoritative one, was presented by the First Presidency at a meeting of the All-Church Coordinating Council on 26 April 1994, entitled simply, “Fundamental Principles.”[15] The first of these fundamental principles was given as “faith in and a testimony of” the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. The only other fundamentals listed were the Atonement and Resurrection, the apostasy and Restoration, the divinely ordained role of Joseph Smith, the Plan of Salvation, the priesthood, ordinances and covenants, and continuous revelation. The document then goes on to list the responsibilities of individuals, families, the church organization, and the community of Saints in general for teaching and practicing these fundamentals. Both kinds of lists in this document (that is, both the principles and the responsibilities) were provided at a rather abstract level, with little or no elaboration, leaving room for a certain amount of interpretation and adaptation to local cultural understandings. I am not aware of any authoritative counterpart of this document prepared for the church membership as a whole, but perhaps one will be forthcoming as members and leaders in various locales undertake to distinguish the minimal core of the religion from American (and other) cultural encrustations.

The fundamental problem, of course, is to protect whatever that mini mal core comprises from the dilution, corruption, or syncretism of the various cultures of the earth, while still welcoming the efforts of Saints in each culture to make the core gospel their own by embroidering it with their folk doctrines, customs, commemorations, and celebrations, somewhat as Guatemalan members have done (see the Murphy paper), and, indeed, just as we do in the United States. For example, American Chris tians (including Latter-day Saints) sometimes point with scorn to the “pagan” remnants in African or Latin American adaptations of Christianity, demanding that the true religion be kept pure. At the same time, however, we seem comfortable enough in our own communities, whether in Utah or elsewhere, in having Christmas trees in our churches, Santa Claus at church children’s parties, and Halloween festivities as part of church youth programs, to mention only a few of the clearly pagan elements in our own syncretism of religion and superstition. Can’t we allow the Saints in various exotic locales to bring in some of their favorite “superstitions” as part of their Mormon experience?

Such a policy might seem more simple and feasible in the abstract than it does in concrete cases. The First Presidency document described above does not mention, for example, “the patriarchal order.” Are we to infer that this traditional LDS concept is therefore not one of the “funda mentals,” or that it is already implicit in the plan of salvation and need not be mentioned separately? If the latter, then what else must be taken as implicit in one or more of the “fundamentals” listed in that document? Insofar as the patriarchal order refers to a pattern of family governance, is it to be understood and applied everywhere in the Victorian terms so characteristic of twentieth-century Utah? If so, perhaps we will hear rejoicing from our sisters in certain Latin American societies, where Victorian patriarchalism would seem to be an improvement over the machismo tradition under which they have been living; or from sisters in certain parts of Africa, where Mormon patriarchy would presumably be preferable to local customs permitting the sale of daughters into marriage and the beating of wives for disobedience. On the other hand, the patriarchal order (understood in the Victorian Utah way) will certainly complicate efforts to adapt the LDS religion in societies (including some of the Native American Indian tribes) where family life has been organized for centuries in matrilineal, matrilocal, and even matriarchal patterns.

Similarly, sabbath observance is not mentioned in the First Presidency’s list of “fundamentals.” Is that because, again, the sabbath principle is to be inferred from one of the other fundamentals on the list; or are the different LDS communities around the world now being left with the responsibility to adapt that principle as best they can to their own local cultural situations? Even in North America, economic, legal, and techno logical changes have long since destroyed the ability of the Saints to observe the sabbath in the rather simple and literal ways possible in an earlier agrarian age. Indeed, much of the work of the church itself would suffer if we all conscientiously observed the sabbath according to the literal prescriptions and proscriptions found in Exodus 20 and in Doctrine and Covenants 59. Interestingly enough, sabbath closing laws and cus toms are now more widespread in some European countries than they are in the United States, not out of any Sabbatarian religious sensitivities but only to be sure that one day a week is set aside for everyone to participate in important community observances, such as athletic activities at schools and elsewhere, various festivals and commemorations, and other totally secular but socially integrative activities.

For LDS members in Europe, Japan, and elsewhere to boycott these important community activities on religious grounds seriously disrupts their relationships not only with some of their closest friends and occupational peers, but especially with their own families, most of whom are not LDS (see the Decoo, van Beek, and Numano essays). Any such disruption obviously increases the “cost” of being an LDS member and might, indeed, prove as costly to the church’s retention efforts (and to its public image) in some countries as it would be (say) to require U.S. Mormons in the hotel or transportation enterprises to close their businesses on Sunday. Can adaptations of the sabbath principle in various cultures be made in ways that will preserve a modicum of integrity in that principle without requiring the Saints in those locales to withdraw, in effect, from nor mal and constructive participation in their respective communities?

How about the nature and structure of LDS worship services or sacrament services in various parts of the world? Must they all conform to the American pattern? Can our African members worship and partake of the sacrament in an environment featuring drums rather than organs, spontaneous enthusiasm rather than sedate speeches? Must we permit only infants the privilege of injecting bodily motion and noise into our services, as in Utah, or can we tolerate more adult counterparts of the same where local tradition defines it as worship? Can the Saints in India publish their own hymnbooks based on their own musical forms, tonality, and instruments? Or does the Holy Spirit, where it is authentically present, impose only one mood and format of worship?[16]

Obviously, similar questions will have to be raised and resolved about many traditional LDS principles, standards, and customs, even after we settle on an essential core of the universal doctrines themselves, if the church is ever to have an appreciable presence in all parts of the world. In such cases local Saints (and potential converts) will be called upon, in effect, to make “cost-benefit analyses,” pitting the blessings of church membership in good standing against the losses of standing and participation incurred in their relationships with families and communities. For some, the cost will prove too high, which will mean that, across time, conversion and retention will be selective. What kinds of people, with what kinds of social and psychological traits and backgrounds, will find the “costs” of church membership acceptable?[17]

The institutional counterparts of these individual cost-benefit analyses pose hard questions too: How much adaptation of gospel teachings and standards can be permitted without running the risk of syncretisms that will cost the religion its integrity? How much do we actually want to reduce the cost of church membership? In our effort to achieve the “mini mal” gospel message that will make it maximally adaptable, what will we have to strip away? Can we afford to dispense with customs, practices, and doctrines (including folk doctrines) accumulated through two centuries of American and Utah experience? Which ones? What becomes of the “Correlation Program” in all of this? Can it be adapted to provide the right mix of world standardization and local autonomy in church governance, programs, and literature? Or should it be repealed altogether? Can local autonomy be extended far enough to give local leaders some participation in the decisions about readiness of candidates for baptism? Or must there remain the traditional “conflict of interest” between missionaries and bishops /branch presidents?

Leaders and members of the church will have to grapple with such questions not only at the general policy level but in applying policy intelligently to each specific cultural setting. The twenty-first century of Mormonism will be a fascinating period in church history. I regret that I can expect to live long enough to see only its first decade or so!

[1] Some of the most recent scholarly literature making use of the idea of a “religious economy” includes Rodney Stark and William S. Bainbridge, The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival, and Cult Formation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985); Roger Finke and Rodney Stark, “Religious Economies and the Sacred Canopy: Religious Mobilization in American Cities, 1906,” American Sociological Review 53 (Feb. 1988): 41-49; and (same authors) The Churching of America, 1776-1990: Winners and Losers in our Religious Economy (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992). What follows here is derived mainly from that literature.

[2] Readers offended by this comparison of religion to a worldly market economy might prefer to think of it as metaphorical or analogical rather than literal. However, in most respects the comparison seems apt even in literal terms. Few students of Adam Smith seem to be aware that even he applied the market concept to an analysis of the religious scene two centuries ago (see Smith’s The Wealth of Nations [New York: Modern Library, 1937 (1776)], 740 et passim.).

[3] One of the intriguing issues about LDS “marketing” is that converts in some societies seem to come from different social strata from those of converts in other societies. Why do converts in North America seem to come from about the middle of the social structure, while those in other societies come from either somewhat lower or somewhat higher strata? Is there a deliberate “marketing strategy” behind any of this? Or (more likely) are there local contingencies making the LDS message more attractive in some strata than in others? (See also n10 in this regard.) This issue could use careful empirical research.

[4] The importance of “marginality” in providing susceptibility to proselyting can be seen in several of the essays in this collection. See, for example, the observation by Bennion and Young that 60 percent of converts in Europe during the past decade have been colonials or other foreigners immigrating from elsewhere (like the African retornados in Portugal), and comparable comments in passing by both van Beek and Decoo about their countries. The same phenomenon is reported about France, over a much longer period, by John C. Jarvis, “Mormonism in France: A Study of Cultural Exchange and Institutional Adaptation,” Ph.D. diss., Washington State University, 1991. While missionaries are as glad to baptize “marginals” as anyone else, church growth, to the extent that it is limited to the margins of any given society, will never be very great.

[5] See Laurence R. Iannacconne, “Religious Practice: A Human Capital Approach,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29 (Fall 1990): 297-314; “Why Strict Churches are Strong,” American Journal of Sociology 5 (Mar. 1994): 1180-1211; and “Sacrifice and Stigma: Reducing Free Riding in Cults, Communes, and Other Collectives,” Journal of Political Economy 100 (1992): 271-92.

[6] On the meaning and measurement of “tension,” and the desirability of “medium tension,” see Stark and Bainbridge, Future of Religion, especially chaps. 3 and 6; or, as I would call it for Mormons, “optimum tension.” See Mauss, The Angel and the Beehive: The Mormon Struggle with Assimilation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), chap. 1.

[7] The unenduring nature of the fascination with American novelty, including religion, is underscored by the recent experience of the church in the formerly Soviet countries. During the late 1980s and early 1990s LDS representatives were welcomed first as American technical experts, educators, and business consultants, often then successfully paving the way for proselyting missionaries. After a very few years of rapid church growth, memberships in some of the Eastern European countries reached into the thousands. Since then, however, massive defections have occurred, due partly to new member disenchantment and partly to government interference with all new religions under pressure from the resurgent influence of the old Orthodox faith. See comments in nl2 of the Decoo paper herein; see also Kahile Mehr, “English Teachers/Gospel Preachers,” and “Serving Body and Soul,” both 1995 unpublished papers on recent LDS history in Bulgaria, and his “The Eastern Edge: LDS Missionary Work in Hungarian Lands,” Dialogue: A journal of Mormon Thought 24 (Summer 1992): 27-45; and Harvard Heath, “Romania and the Mormons: Past Perspectives and Present Problems and Predictions,” paper presented at the annual meetings of the Mormon History Association, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, 22 June 1995.

[8] See Marcus H. T. A. Martins, “The LDS Church in Brazil: Past, Present and Future,” paper presented at the joint annual meetings of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion and the Mormon Social Science Association, St. Louis, Missouri, 27 Oct. 1995.

[9] According to President James Faust, the church has contributed such humanitarian services in as many as 114 countries during the past decade or so (Ensign 25 [May 1995]: 61). From friends who have recently served as LDS “humanitarian” missionaries, I know that these services, along with many material, infrastructural installations, are offered especially in Third World Asian countries from Mongolia to Indonesia to Vietnam to India, irrespective of the prospects for LDS proselyting access in the near future. Nor is it only Third World countries where this occurs. The church has started its relationships with several of the formerly Soviet countries through humanitarian or educational endeavors. See, for example, unpublished 1995 papers in n7 by Mehr and Heath.

[10] Aside from questions of local cultural sensitivity, Decoo also makes the important practical point that dependence on tracting in any country runs the risk of systematically by passing millions of people not usually at home during the day; many of these are professional people of talent and substance who might be receptive to the gospel message if permitted to study it on their own initiative and at their own pace through use of the Internet. Interestingly enough, Marcus Martins makes exactly the same point about Brazil (see n8).

[11] J. Reuben Clark, “When are the Writings or Sermons of Church Leaders Entitled to the Claim of Scripture?” Church News, 31 July 1954, as reprinted in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 12 (Summer 1979): 68-81.

[12] See Alexander, “The Reconstruction of Mormon Doctrine: From Joseph Smith to Progressive Theology,” Sunstone 5 (July-Aug. 1980): 24-33; Jan B. Shipps, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985); and Bruce R. McConkie, “All Are Alike Unto God,” address to Church Education System faculty, 18 Aug. 1978, copy in my files.

[13] See President James E. Faust, “Heirs to the Kingdom of God,” Ensign 25 (May 1995): 61-63, and President Gordon B. Hinckley, “This Work Is Concerned with People,” Ensign 25 (May 1995): 51-53.

[14] See “The Basic Doctrines of the Gospel of Jesus Christ Essential to Developing a Religious Education Curriculum as Revealed to Ancient and Modern Prophets,” identified as a “supplement” approved by the Church Board of Education on 5 March 1971 (copy in my files). Among the doctrinal propositions that some members might find questionable, or at least superfluous in the world church, are (depending on how they are interpreted): “B.3. Every individual born on this earth comes into a lineage according to a pre-earth-life determination”; “C.4. All things on earth have a purpose in (the) creation”; “H.8. Through the preaching of the gospel to the nations of the earth, Israel will be gathered”; and “H.9. Preceding the second coming of Jesus Christ, Zion must be established as a place and a people.”

[15] Copy in my files. The document ends with the instructions that “adherence to these principles will help accomplish the mission of the Church and the purpose of God ‘to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man'”; and “please teach these principles as would the Savior, with love, understanding, patience, testimony, and charity,” all qualities that will be especially crucial in dealing with the Saints in various cultures.

[16] On the problematic aspects of worship styles among LDS congregations in West Africa, especially in regard to influence of the Holy Ghost therein, see E. Dale LeBaron, “A New Religion in Black Africa: Mormonism and Its African Challenges,” paper presented at the joint annual meetings of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion and the Mormon Social Science Association, St. Louis, Missouri, 27-29 Oct. 1995. On the prospects and desirability for LDS members in India to create their own hymns, see Roger R. Keller, “Cultural Challenges to the LDS Missionary Effort: Focus on India,” paper presented at the Mormon Studies Conference, University of Nottingham, England, 6 Apr. 1995.

[17] In this connection, please refer again to nn3 and 10, above.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue