Articles/Essays – Volume 22, No. 2

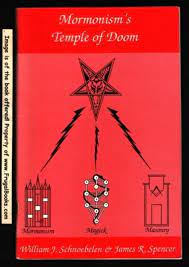

Mormonism, Magic and Masonry: The Damning Similarities | William J. Schnoebelen and James R. Spencer, Mormonism’s Temple of Doom

The lurid title notwithstanding, this little book is not a sequel to Indiana Jones, but rather an expose of damning parallels between Mormonism, magic, and Masonry. The authors (most of the story is Schnoebelen’s, with Spencer contributing an intro duction) are moved, they write, by com passion for Mormons who participate in satanic rituals without knowing their true meaning. The book walks its reader through the temple ceremony and its symbols from the perspective of a man who has spent his adult life moving through the ritual hierarchies of witchdom, Freemasonry, and Mormonism, and who ends his chronology (illustrated by reproductions of degrees, recommends, and certifications) with the exclamation “SAVED!!!”

The parallels Schnoebelen points out between Mormonism and Masonry have been documented dozens of times. Joseph Smith and his associates were indeed Ma sons, and our temples and temple rite indeed owe much to Masonic iconography. Here the author is on firm historical ground. That ground grows swampy, however, as he attempts to identify the symbols of Mormonism and Masonry as satanic.

The author sometimes convinces as he connects the three ritual systems (similar symbols, grips, tokens, phrases, etc.); but more often he sets off on flights of fancy (as when he relates tokens of the Melchizedek Priesthood “to a Great Point on the circulation/sex meridian. Used in magic to alter sexual alchemy to enable magicians to marry demon spirits” or argues that the veil a woman wears in the temple relates her to the “Veiled Isis . . . the Consort of Lucifer . . . the keeper of the mysteries of sex and devil worship” (pp. 45 and 33). These examples of authorial credulity, just two of many which could be cited, illustrate two of the author’s beliefs which are interesting beyond the merits of a book that becomes a tirade (“vampiric revulsion,” “the ceremonies within are festering cankers of Satanism,” etc.). The “demon spirit” example reveals that for the author signs/symbols/tokens have real magical power; the veil discussion shows that for him symbols mean the same in all times and contexts.

Schnoebelen assumes that if you have seen one veil you have seen them all. And the one veil he recognizes is the veil of Isis he saw as a wizard of a “Druidic Rite” or as a warlock of a “Church of Satan.” Interpreting veils from another tradition (Old Testament or Islamic, for instance) he would surely come to a different conclusion. But with a single, exclusive interpretive lens, myopia is unavoidable. Schnoebelen might do well to note the Old Testament peoples who adopted symbols of their pagan neighbors and successfully filled them with content true to their own God Jehovah. This is not to say that there are not offensive symbols. When enough of us share a background against which a symbol conveys something offensive — like the characterization of the devil as a man with a black skin — the symbol itself is changed. If the inverted pentagrams Schnoebelen finds so offensive on the Salt Lake and Logan temples were to indeed become “universally regarded as an evil symbol,” we would simply have them chiseled off the walls (unless, as Schnoebelen would believe, we are meant by conspiratorial leaders to be “drawn into an ever tightening web of occult rites and deception” (p. 34).

Schnoebelen may not be wrong to identify our symbols as offensive in the con text he has built in his own mind by practicing witchcraft; but to judge our symbols as universally evil is absurd. Contemporary use of the word “gay” is a good example of how a new meaning preempts an old one; and all of us past adolescence are sophisticated enough not to read usages of another time or context as proof of the user’s sexual inclination.

Symbols, by their very nature, resist exclusive, never-changing interpretation. Only a committee of lawyers could presume to draft a ritual with a single, static meaning; and the brighter among them could find ambiguities in whatever text the others found conclusive. Schnoebelen has no such insight. For him a veil is a veil; and the green of an apron cannot relate to fig leaves or to the Boston Celtics, but must be “Lucifer’s color! . . . Green is his color first because it relates qabalistically (sic) to Venus. Venus, the ‘Morning Star,’ is sacred to him. Alchemically, Lucifer is related to copper” (p. 22). My freshman literature students would hoot me out of the classroom if I began such free association.

But beyond his insistance that a single symbol have a single meaning in all historical circumstances, it is Schnoebelen’s other assumption that really interests me. Although he has ostensibly left magic, Masonry, and Mormonism behind to enjoy his present saved condition, he still believes in a basic tenet of magic: that signs have actual physical and metaphysical power. When he writes, for instance, that he “cannot find any other place where the inverted pentagram is used outside Satanism. It is just too evil a sign — it draws demons!” (p. 49), he reveals what might be called idolatry, an inability or unwillingness to see beyond or through a symbol to what it signifies. This belief in the magical power of signs is interesting not because the author of a compassionately scurrilous pamphlet believes that our temple ceremonies “can cause spiritual — and sometimes physical — harm to the participant” (p. 9); but be cause the issue of magic versus metaphor is one that we as Mormon temple-goers might profitably discuss.

Freemasons of the late eighteenth century debated this issue in terms that shed light on our own ritual practice. The con text of their debate was a broader European discussion about the nature of language. In his book The Order of Things (New York: Vintage, 1973), Michel Foucault points out that prior to the eighteenth century, people had generally assumed that the words with which they communicated were natural, that is, directly related to the things or ideas they signified. (This belief stemmed in part from the account in Gene sis in which Adam names the animals in the garden, using an Adamic language in which the name is perfectly adequate to the thing named, in which the name partakes of the nature of the thing.) According to this belief, then, for example, the word “gold” should contain the essence of the metal; and so alchemists sought in the word itself the secrets of making gold. In the eighteenth century, however, Locke, Condillac, Rousseau, Herder, and others began to argue that language is not natural, but rather arbitrary. The sign is but a convention we agree on to designate something. They could point to language after Babel to make this point; for if the word “dog” partakes of the essence of dog-ness, then why do the Germans call the same animal “hund” and the French “chien”? If language is indeed arbitrary, then words no longer have magical power, for they no longer directly relate to the thing over which they are supposed to exert power.

For most of the eighteenth century this sense for language as arbitrary fit Freemasons’ sense for their ritual just fine, for they saw their elaborate system of symbols as a rhetorical tool for teaching moral principles, and not as magically efficatious. But the lure of magic remained (as it does in any ritual system ) ; and confidence men like Saint Germain and Cagliostro traveled through Europe revealing an esoteric, magical Masonry which promised wealth and supernatural knowledge untold. Pitched battles were fought between the two sides over the issue of metaphor versus magic.

The metaphor camp interpreted their symbols as we do the tropes of a good poem: as revealing knowledge not otherwise accessible, but knowledge still very much limited to the realm of human language. In the magic camp, however, the symbols became esoteric keys to supernatural power and glory: gold could be made from base metals, spirits could be called up from another world. The first group saw the second as fallen from the heights of rational enlightenment, given over to superstition; and the second group found their brothers caught in a sterile, non-transcendent world.

There is plenty of evidence that many of our ancestors saw symbols of the temple ceremony as veritable keys to heaven and as magically potent here on earth. In fact, most of us still harbor some superstition in that regard. But clearly, knowing a secret sign will do us no good now or later unless the sign has helped us know what lies behind it. Unless we have been taught and changed we are left holding worthless currency. (Otherwise any mass-murderer in possession of the often-printed temple ceremony has nothing to fear.) The power is not in the symbols, but in Jesus Christ, whose atonement can be read in any of the symbols if we read well and don’t seek salvation in the sign itself.

Mormonism’s Temple of Doom by William J. Schnoebelen and James R. Spencer (Idaho Falls, Id.: Triple J. Publishers, 1987), 79 pp., $3.50.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue