Articles/Essays – Volume 17, No. 4

Mythology and Nuclear Strategy

Nearly everyone talks about nuclear weapons and our nation’s nuclear policies and strategies. Yet very few of us understand even the most elementary vocabulary of the subject. Why should terms like “counterforce” and “countervalue,” “first strike policy” and “first use policy” be so foreign to us when they are kindergarten-level words to Pentagon planners and government decision-makers?

The obvious answer lies in what psychiatrist Robert J. Lifton calls “psychic numbing.”[1]When we try to grasp the true scope and import of the nuclear arms race, we are almost immediately overwhelmed. There is nothing in our experience that even begins to touch the necessary scale of annihilation. We know about the deaths of individuals, of whole societies, even of immense empires. But how can we possibly comprehend the death of the human species, much less the entire planetary biosphere?

So our minds go blank. They simply shut down and refuse to attempt to grasp the issues involved. We become numb; and we find ourselves leaving it to the “experts,” comforting ourselves with the assumption that it’s all too com plicated for us anyway. Why bother to learn all those technical terms? What good would it do?

Lifton’s theory of psychic numbing is certainly invaluable in explaining our attitudes toward the nuclear issue. But I think that it only gives us half the picture. It tells us why we don’t think very much about the nuclear threat darkening our horizon. As a historian of religion, I have been led to look at the other half of the picture: What happens when we do think about nuclear war? My answer, in brief, is that we mythologize.

To illustrate this point, let us look briefly at the major options for nuclear strategy that have governed our national policy. For the first decade or more of the nuclear age, the new weapons had little impact on our basic approach to war. Most Americans continued to view war in their traditional way, as a battle of total good against total evil. Historians of religion know this as a variation on a mythic theme of nearly universal distribution: the heroic war rior prepares to slay the evil monster. Since the monster will show no pity, the warrior must arm himself with a magic weapon. While the heroic warrior must be willing to suffer and perhaps even die, he knows that he will rise again and triumph in the end, for he has right, truth, and the invincible weapon on his side.

This mythic scenario has never vanished from American consciousness — or at least unconsciousness — and it has flourished again in recent years. It became more difficult to sustain when the monster, in the form of a demonic red bear, obtained the same magic weapon for himself. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, necessity became the mother of a new strategic policy — deterrence. Deterrence, as understood in the public mind, is also a variation on a wide spread mythic theme. The bombs which had been a lethal weapon now became a magic shield, an inviolable wall guaranteeing peace and security. As long as the wall stayed high enough, those within its sheltering confines could look for ward confidently to a restoration of Camelot, if not of the Garden of Eden itself.

Of course the demonic red bear also loudly proclaimed that his sword had been transformed into an equally inviolable wall. And somehow the idea spread abroad that no wall was high enough unless it was higher than the enemy’s wall. So the conversion from war-fighting myth to deterrence myth did nothing to slow down the arms race. Indeed, the arms race accelerated rapidly during the 1960s.

Recent interpretations of American nuclear policy suggest a new explanation for this puzzling phenomenon. While the government has publicly pro claimed its goal to be simply deterring a Soviet attack on the United States, these interpretations claim that privately it has used its nuclear arsenal to deter any Soviet foreign policy moves of which it disapproves. The potential for non nuclear Soviet intervention in Vietnam, the Middle East, Iran, and elsewhere has been forestalled, in our government’s view, by the intimidating size of our nuclear arsenal and our willingness to use it.

If these interpretations are substantially correct, then we must reckon with a third mythic theme. For it seems that deterrence is not simply a retreat into inviolable, womb-like safety. It also reflects a desire to keep the monster penned up in his lair while we are free to dominate events around the world. One sees here a wish to become omnipotent, lords of the political universe. That human beings aspire for divine powers is, of course, a mythic theme known throughout the world. But it may have special meanings in our own cultural situation.

Both the United States and the USSR are historically rooted in Christian monotheism and in monarchies claiming to embody the one God’s power on earth. In both countries, revolutions rejected much of these traditions. But while visible branches can be lopped off, subterranean psychic roots stubbornly remain. Although these revolutions posited the value of human freedom above religious institutions, they did not erase the assumption that a single power might — perhaps should — rule over all. Nor did they erase the image of the man who was God. In some subtle ways, freedom may have become equated with the omnipotence of divinity placed in the hands of mere mortals. So it may not be surprising that our president at this writing is so openly enamored of apocalyptic politics. But I suspect that previous presidents and Soviet party chairmen dreamed much the same dreams, though they had the tact and good sense to keep them private.

Elements of the apocalyptic mythos are not confined to this third scenario, however. The key themes of the apocalyptic tradition are also the common thread running through all three strategic options we have just surveyed: a mythic dualism articulated in political terms, a universal struggle between the forces of order and the forces of chaos, hope for a permanent victory over the chaos-monster, and trust in a superhuman power to achieve this victory. With such a unified vision at the core of all three strategies, it is understandable that the public is not very interested in distinguishing among them.

For I suspect that when we pay attention to the nuclear weapons issue, what we see and hear and feel are overwhelmingly mythic and symbolic images. These images are so compelling and appealing and satisfying, albeit largely in unconscious ways, that we find no reason to look any further. The examples I have offered from the realm of nuclear strategy are only a small fraction of the endless stream of myth, symbol, and fantasy images that flow from the bomb. Once you start wandering through the lajbyrinth of nuclear thoughts and feelings, you find new images turning up around every corner. If you are a historian of religion, most of them look surprisingly familiar, and their appeal is not too difficult to decipher.

So psychic numbing is only half the story. It tells us why we fail to face the nuclear issue. The mythic approach tells us what happens when we do face the issue: We are fascinated, deeply moved, and somehow fulfilled in ways which we only dimly perceive or understand. Numbing and mythologizing thus rein force each other, and the upshot of this secret alliance is political paralysis. Immobilized from both sides, we fail to dismantle the trap which we ourselves have made.

Is it simply an unhappy coincidence that numbing and mythologizing happen to foster the same results? I don’t think so. As I have tried to formulate a theoretical model for understanding the nuclear dilemma, I have been drawn to explore the manifold logical and psychological connections between these two phenomena. One direction that I see as fruitful for future research begins with Lifton’s understanding of the roots of psychic numbing. He claims that numbing reflects a breakdown in the formative process of inner mental imagery. A numbed mind loses touch with its own resources for experiencing the mythic dimension. Hence it is confined to the literal level of truth as its only access to truth.

The same could be said, I believe, for a numbed society. If one asks whether the tyranny of literalism in our time is effect or cause of psychic numbing, the answer, no doubt, is, “Both.” The declining power of myth and symbol in modern Western culture has not erased our desire for them, however. If anything, it has increased our appetite, as hunger always will. Yet where can we go for publicly shared mythic experience? Defining all meaningful truth as empirical literal truth, we have relegated the traditional media of myth — art, literature, dance, even film and TV, which could be mythic media par excellence — to the realm of “mere entertainment” and thus unreality.

But myth is not truly compelling or satisfying unless it can be lived out as an integral part of the real world. Myth is, ideally, a vehicle for containing and expressing our deepest and most genuine experiences. When we live within a mythic structure as part of our real lives, we can feel the joys and sorrows of life with an intensity that would otherwise be overwhelming. Mere entertainment is a lifeless substitute, a one-dimensional caricature of myth that limits, rather than enhances, our capacity to feel, and thereby helps to keep us numb.

So while the conscious mind accepts, and even acclaims, its mythless modernity, the unconscious still searches for a mythic dimension in the reality of things. Well, what could be more mythically appealing than an epic struggle for supremacy between the world’s two mightiest powers? Only one thing: a struggle in which the continued existence of the species itself hangs in the balance. And we have both! Aren’t we lucky?

I believe that, on some unseen ground floor of the psyche, we do feel lucky, for we have a profoundly mythic foundation to our collective lives. The irony, though, is that we are too numbed to experience it in any conscious way as myth. Consciously, we label it as literal reality and deny its mythic meaning. Unconsciously, having trained ourselves to see all myths on the rather banal level of entertainment, we perceive nuclear myths in much the same way. So a movie actor turned president can proclaim a Star Wars scenario as the next step in nuclear strategy, and no one blinks an eye. The line between politics and theater, TV news and soap opera, was crossed long ago.

I would submit that the mythologies of nuclear war and nuclear weapons, as we experience them, are pseudomyths. They are built of mythic themes and structures, but they fail to communicate the rich multi-dimensional truths and depths of feeling that genuine myths embody. For a society bereft of all other myths, however, these myths have immense appeal because they are the best we have. Conjuring up age-old images of heroic warriors, omnipotent god-men, the end of the world, the rebirth in fire, and so on, they touch, however lightly, our need for such images, when nothing else does. So they seem to appease our hunger for myth, and we are satisfied with them, seeking nothing further. Indeed, we cling desperately to them, for they are the stuff of which our world view is built. We live by these schematized pictures of the world, and we may very well die by them. For the history of religion teaches us with ample lessons that people are often willing to die rather than give up their most cherished beliefs.

The model I am exploring, then, is one of psychic numbing and mythologizing which foster each other in a vicious psychological circle. Because nuclear myths are mere caricatures of true myth, they are unable to break through our numbing. But because they pass for true myth, they allow us to feel comfortable in our numbing. The more our numbing grows, the more committed we are to defining all truth as literal truth. Seeing our nuclear myths as literal truth — denying that they are myths —- we become even more firmly immobilized and numb. So we feel a more desperate need for myths, no matter how superficial; hence we immerse ourselves more deeply in our nuclear myths, and the cycle begins all over again.

Can this circle be broken? I don’t know. I suspect that we don’t have enough time. But if there is any chance to break it, the place to start is with awareness of our need for myth. Once we understand the nuclear arms race as part of a search for viable public myths, we are on the way to breaking out of the trap of pseudomyths held as literal facts. We take a step back from the whole issue, see it in a new and wider perspective, and thus see alternatives that we previously obscured.

When we perceive politics as myth, we begin to make contact with that “formative zone” of our minds which Lifton claims is the key to overcoming psychic numbing. Doing so, we realize that it is neither feasible nor desirable to call for a demythologizing of the nuclear issue. An awareness of the mythic dimension should rather stimulate a remythologizing—a search for new myths and images that can lead us away from the brink of annihilation. We need not look very far for these myths. In surveying the prevailing approaches to strategy, we have discovered the enduring appeal of some fundamental mythic themes and scenarios, which we cannot expect to abolish. But we have also discovered how malleable and open-ended these themes are, how easily these skeletons take on new flesh.

We cannot abandon our dream of becoming heroic warriors and vanquish ing the evil monster forever. But we can learn that the monster is not another group of human beings who happen to speak a different language or butter their bread on a different side. This doesn’t mean that we transform the world overnight, wake up the next morning, and make friends with the Russians. Certainly there will be rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union for some time to come.

But the problem is essentially one of myth, and myths are hierarchical in our minds. That is, we hold many myths simultaneously, myths which are the source of our values and actions. But some take precedence over others. So I would suggest not that we eliminate the myth of “us against the Russians” altogether, but that we demote it a peg or two and put in its place, as our con trolling myth, “us against the nuclear weapons.” “Us” then becomes Ameri cans, Russians, and all people of the world. For in the nuclear age, there truly is no longer an “us” or “them” in human society. We are all “us” and either we all survive together, or we all perish together.

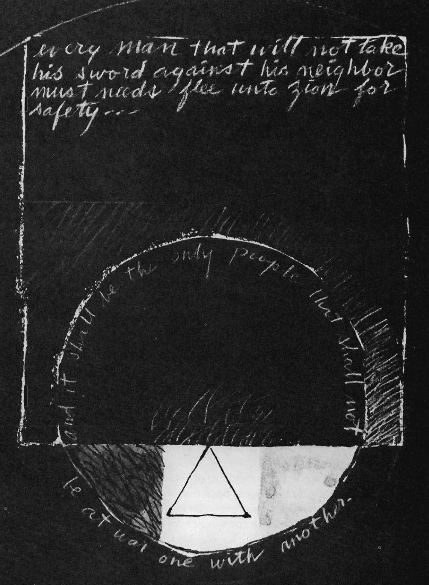

The demonic monster today is the network of nuclear weapons blanketing the earth and turning it into one enormous bomb. Like the hero of old, we must be willing to face the monster head on. Yet we need not feel like the young David, taking on Goliath by himself or Judith walking with her maid into Holofernes’ camp. Rather we can take as inspiration the ancient stories telling of those who banded together to brave mortal peril. Like the crew of Odysseus, the knights of King Arthur, or the three hundred men of Gideon, we too can find strength in numbers. Each of these stories reminds us, though, that the monster may prevail unless some individual steps forth to lead the fight against it. Today, in an age notoriously bereft of heroes yet faced with the greatest peril ever, who among us can afford the luxury of waiting for someone else to step forth?

These stories remind us, too, that facing the monster means quite literally looking at its true visage, in the fullness of its terror. Today we need new images of nuclear annihilation, images more radically grotesque and horrifying than anything we have permitted ourselves thus far. These new images are themselves a crucial force for breaking through our psychic numbing. But we will not be able to endure them unless they are coupled with a myth of survival and renewal. So we recall that the dream of permanent security behind in violable walls is also a universally appealing motif. We still yearn to return to the sheltering glades of Eden, to rebuild the ramparts of Rome, to construct the New Jerusalem. Our task now is to envision those walls fashioned not out of bombs but out of mutual agreements to ban omnicidal weapons. Appeals to reason alone will not achieve this goal. It must be powerfully depicted in myth and symbol.

The struggle for nuclear disarmament can itself become the source of a new and immensely potent mythic drama. It can embody for us a truth which is of the essence of myth: that death is a part of life which can be accepted precisely because it is not the whole. Precisely because it is only a part, death need not swallow up the whole. But only when it is accepted as a part can it be prevented from swallowing up the whole. A love of life alone, no matter how passionate, will not save us in the nuclear age. We must learn once again to reach down to the deepest heart of the mind, the place from which we can love the whole cycle of life and death together. Perhaps by living out both nuclear death and nonnuclear rebirth in mythic imagination, we can touch this deepest heart and avert a world-wide death which would also be the death of all rebirth.

[1] Lifton first developed his theory of “psychic numbing” in his study of Hiroshima survivors, Death in Life (New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1967). It is developed most fully in his The Broken Connection (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979). For a good summary, see Section I of Robert Jay Lifton and Richard Falk, Indefensible Weapons (New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1982).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue