Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 4

New Light on Old Egyptiana: Mormon Mummies 1848-71

In 1966 eleven pieces of Egyptian papyri, known to have been part of a small collection of four mummies and some papyri owned by a certain Michael Chandler which Joseph Smith acquired in Kirtland, Ohio, in 1835, were dis covered in New York City. It was a find that created considerable excitement.

This paper attempts to throw some new light on the history of this Mormon connected Egyptiana since 1848 (the close of the Mormon era in Nauvoo) and to suggest how and where more of these antiquities might be found. The search moves through four locales: Saint Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Western Illinois. Though hardly crowned with new finds, collectively, these four locales represent one of the most fascinating and frustrating research ad ventures of my career as well as a substantial body of negative evidence.

On 14 August 1856, Wyman’s Saint Louis Museum advertised in the Saint Louis Missouri Democrat that “two mummies from the Catacombs of Egypt” were on exhibit. Fifteen years later, on 19 July 1863, the Saint Louis Missouri Republican reported “The museum . . . will close next Saturday and remove to Chicago.” These two accounts bracket what is known about two of the four Mormon mummies and some papyri which were exhibited in Saint Louis during the midnineteenth century.

Thanks to the seminal work of James R. Clark, and later efforts of Walter Whipple and Jay Todd, the story of how these two mummies and some of the papyri found with the mummies got to Edward Wyman’s Saint Louis Museum is fairly well understood.[1] In general, we also know what happened to these antiquities while they remained in Saint Louis until sold to Chicago in 1863.

Since I live in St. Louis County, I have for years, off and on—mainly off—addressed myself to the task of finding out more about the mummies/ papyri during their Saint Louis sojourn of eight years.

J. P. Bates, Wyman’s curator-agent-collector, probably effected the pur chase in 1856, but little is known of him. City directories identify him as a naturalist and preparer of birds during this period and his reputation was that of “the enamoured naturalist, not the adroit showman.” He accompanied the collection to Chicago in 1863.[2]

Looking into the career of Edward Wyman, founder of Wyman’s Hall which housed the Saint Louis Museum, is only slightly more rewarding. He was an educator from the East who came to Illinois in 1836 and to Saint Louis in 1843 where he established an English and classical high school. Since his school contained an excellent auditorium, it was frequently booked for local and traveling exhibits and performances, including that of Jenny Lind and Tom Thumb. Apparently catching show business fever from such exhibitors, especially from P. T. Barnum, who accompanied Jenny Lind in 1851, Wyman turned his school first into a theater and then added a museum. He was, however, not a good showman—too serious and honest and he went into debt, lost control of his building, returned to academic life, and died in Alton, Illinois, in 1888. Available papers, including those from his estate, turned up no references to the mummies.

About a month after the mummies/papyri went on exhibit in Saint Louis, a local scholar visited them, Professor Gustaf Seyffarth, a controversial Egyptologist from Leipzig, then visiting professor at the Concordia Seminary of the Lutheran Synod in Saint Louis County. His observations appeared in the St. Louis Evening Pilot 13 September 1856: “Visitors will find also some large fragments of Egyptian papyrus scrolls, with pieratic [hieratic] (priestly) inscriptions, and drawings representing the judgment of the dead, many Egyptian gods and sacred animals, with certain chapters from the old Egyptian sacred books.” Seyffarth is quoted in the 1859 catalog of the Saint Louis Museum as saying that “the papyrus roll is not a record, but an invocation to the Deity Osiris . . . and a picture of the attendant spirits, introducing the dead to the Judge, Osiris.” Unfortunately much research into the life and papers of Seyffarth turned up nothing further regarding his opinion of the Mormon mummies.[3]

I had more success in the Saint Louis press. The mummies, we learned in 1966-67, were sold in Nauvoo 26 May 1856, but when did they come to Saint Louis? On 13 July 1856, the Sunday St. Louis Republican referred to “Egyptian antiquities” in Wyman’s Saint Louis Museum, but it does not necessarily refer to the Mormon antiquities. The Daily Missouri Democrat of 14 August 1856, however, specifies that the exhibit is of “two mummies from the catacombs of Egypt, which have been unrolled, presenting a full view of the records enclosed, and of the bodies which are in a remarkable state of preservation.” The same issue of that paper contains a second notice of the “new attraction.”

On 13 May 1857, almost a year later, the Daily Missouri Democrat headlines a short account: Jo. Smith’s Mummies. It noted that these mummies had been purchased in 1856 and added, “Some of the brethren have had the hard ness to deny that these were the patriarchal manuscripts and relics. But an unanswerable confirmation of the fact has lately occurred; certain plates issued by the elders as facsimiles of the original having fallen into Mr. Wyman’s hands, which plates are also facsimiles of the hieroglyphics in the museum.”

The “brethren” and “elders” seem to refer to the discomfort of some Saint Louis Mormons with Wyman’s identifying his mummies as those connected with the book of Abraham. They were probably offended as well with Wyman’s 1856 catalog announcement that “Joe Smith, the Mormon Prophet,” had originally bought them on account of the writings “found in the chest of one of them, which he pretended to translate.”[4]

The “certain plates issued by the elders as facsimiles of the original” can only refer to a reproduction of what we know today as the current Pearl of Great Price’s Facsimiles 1, 2, and 3. In fact, the first (1851) edition of the Pearl of Great Price or the book of Abraham publication in the Times and Seasons in Nauvoo, Illinois, of 1 and 15 March and 16 May 1842 are the most likely candidates.

When we combine what Seyffarth wrote in 1856 about the “judgment of the dead” and in 1859 about “an invocation to the Deity Osiris” with the story in the Missouri Democrat it seems quite clear, as Jay Todd pointed out in 1969, that Seyffarth may well have been looking at what have since been labeled the Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri “IIIA. and IIIB. Court of Osiris,” or perhaps Facsimile No. 3 in the Book of Abraham.

If Seyffarth had indeed been looking at the Court of Osiris fragments in 1856, it means that these fragments survived the Chicago fire of 1871, to be rediscovered in 1966, suggesting that the two mummies and other pieces of papyri once in Saint Louis and Chicago may also have survived the fire. How ever, from the Missouri Democrat description Seyffarth was likely examining the original of Facsimile No. 3, which, as far as is known, did not survive the Chicago fire.

The Democrat ended its account by chiding the local Mormons: “Let them, all of Mormon faith go to the museum, and contemplate the veritable handwriting of the patriarch Abraham. Who knows that the patriarch him self, ‘and Sarah his wife,’ are not in the museum?”

Apparently this story did not completely satisfy some of the “brethren” who seemed to have found it very difficult (as do some Mormons today) to accept the idea that Brigham Young would go west without these presumed sources of the Book of Abraham and that the antiquities would ever be per mitted to pass out of church ownership and put on public exhibition in Saint Louis as money making curiosities. (Although “Mother Smith” exhibited them for years in Nauvoo for a fee.) So the same paper printed a second article on 12 June, “The Mormon Prophet’s Mummies,” noting, “Doubts still being expressed that they were the prophet’s mummies, etc., . . . we now append the certificate with which the sale of them to Mr. Combs was accomplished.” The paper then printed in full a document which would not see the light of day again for over a century — namely the 26 May 1856 bill of sale which came to light in 1966 in New York City. Its publication in 1856 proves beyond any doubt that the Saint Louis Museum indeed exhibited the Mormon antiquities and that an A. Combs was the middle man.

There were certainly other mummies in Saint Louis before and after the Mormon ones. At least five museums predated Wyman’s. Albert Koch’s (1832-41) exhibited “an Egyptian Mummy, together with the Sarcophagus or Coffin, which is supposed to be more than three thousand years old,” according to a 27 January 1836 sttory in the Missouri Republican. In 1841 Koch sold his collection to a museum in New Orleans and nothing more is known of this particular mummy.[5] (If I may be permitted to enter the realm of speculation for just a moment, I could hypothesize, rather wildly, that Koch’s mummy might have been one of the seven mummies Michael Chandler sold before he disposed of his remaining four to Joseph Smith in Kirtland in 1835.)

While the Mormon mummies were on exhibit in Saint Louis at least one other Egyptian antiquity was exhibited briefly in that city. The Missouri Democrat of August 1856 notes that the famous steamboat, Floating Palace, was “at the Steamboat landing with 100,000 curiosities” including “ancient relics from Egypt, Rome, Pompeii, and Herculaneum.” The Missouri Demo crat of 22 September 1857 also reported that the Saint Louis Museum was negotiating to buy Peal’s Baltimore Museum collection, which included one Egyptian mummy. There is no evidence, however, that this ever happened.

Although several museums operated in Saint Louis after the collection of the Saint Louis Museum was sold to Chicago in 1863, there is no evidence of Egyptian antiquities in the city until about 1896 when Charles Parsons donated two mummies to Washington University. One is currently housed at the Saint Louis Museum of Science and the other is located at the Saint Louis Art Museum. In 1928 Washington University acquired a third mummy from the Smithsonian Institution, currently on exhibit in the Museum of the Department of Anatomy of the School of Medicine of Washington University.

Another mummy was briefly in Saint Louis during the 1904 World Fair as part of the Egyptian exhibit, afterwards acquired by the Louisville, Kentucky, Museum. Unfortunately there is not a shred of evidence that any of these mummies is connected in any way with the Mormon ones. While these first two mummies are very richly appointed and in beautiful sarcophagi — therefore most assuredly not “our mummies” — the third one in the School of Medicine is a blackened, ugly object. About 1955 a certain E. De Mar Ander son, M.D., of Seattle Stake, saw it, decided that the blackness was a result of the Chicago fire, and reported that it indeed was “our mummy.” The black ness of the mummy, of course, is simply the result of the embalming process.[6]

Why and when was the Wyman collection sold to Chicago in 1863? Dur ing July 1858, Wyman failed to settle a debt of $12,000, losing his hall and collection to a Saint Louis businessman, Henry Whitmore.[7] Five years later two businessmen in Chicago bought out a certain Thomas Lawson who had bought out Whitmore. The Missouri Republican notes on 3 July 1863 that the Saint Louis Museum “will shortly be removed elsewhere.” On July 9 it announced that the museum “will close next Saturday [July 12] and remove to Chicago.” And so it did.

II

The Chicago story is less well known than the Saint Louis one. After months of work and grief, reading all the extant Chicago papers for the proper period, I unraveled the details of the sale of the Saint Louis Museum, its removal to Chicago, and its history until the fateful night of 8 October 1871 when downtown Chicago was incinerated. That intermediate history is very sparse. In one way or another the collection passed through the hands of at least twenty owners, managers, and exhibitors, not one of whom left any papers I could find in Chicago or Springfield, Illinois.

There are, however, a few more details in the early years. On 6 July 1863 the Chicago Tribune announced “with pleasure that through the liberality of two of our worthy and public spirited citizens [John Mullen and John M. Weston] the Saint Louis Museum has been purchased, and will soon be re moved, and permanently located in this city. This museum is much the largest in the West, and in several features the choicest one in the United States.”

This new Chicago Museum was housed in what was then known as Kings bury Hall at 111-117 Randolph Street. The new owners quickly printed a Guide to the Chicago Museum; the entry on the mummies simply reprints what had appeared in the 1859 catalog of the Saint Louis Museum.

During August other stories informed Chicagoans of the new museum.[8] On August 10 the Chicago Times noted, “There are the two mummies which in the hands of Joe Smith were made to give a revelation and still they bear the original tablets with the cabalistic or coptic characters thereon.” This reference to a “revelation,” while not common, had been made several times before by non-Mormons. A possibly more significant statement, however, is the reference to tablets, probably “mummy tablets” which were usually attached to the toes of mummies as a means of identification after embalming and wrapping. They were widely used, were usually about two by six inches in size, were made of wood, stone, ivory, or even marble, and usually bore the name and title of the deceased, and a short prayer.[9] Since they generally date from the second or third century B.C, their presence on the Mormon mummies reinforces the few other specifics we have regarding their tomb in suggesting that the mummies are not of Abraham’s day.

On September 3, the Chicago Times published a rather funny, but in formative article, titled, “What an Old Lady Thought About Mummies.”

An old lady at the Museum a day or so ago, coming suddenly upon a case containing two Egyptian mummies was extremely horrified at their exhibition without clothing of any kind, and showed symptoms of an intention to hold her nose until assured that, notwithstanding the long interval since their decease, no disagreeable odor was emitted. She was not long in betraying still greater ignorance by remarking to the young girl who accompanied her,

“Sairy them critters is of African descent true as preachin, and that accounts for their not being burried like white folks and Christians.”

“These are mummies, madam,” remarked a gentleman who stood nearby, endeavoring to control his inclination to laugh heartily at the old lady’s speech.

“Wall,” returned she with renewed indignation, “I don’t keer whose mummies they be, its a tarnal shame to have human being dug up and made a show of, even if they be niggers. But its just like them poky southerners to beat their colored brothers to death and then stick them in the ground with nary stitch of clothing on to hide their nakedness.”

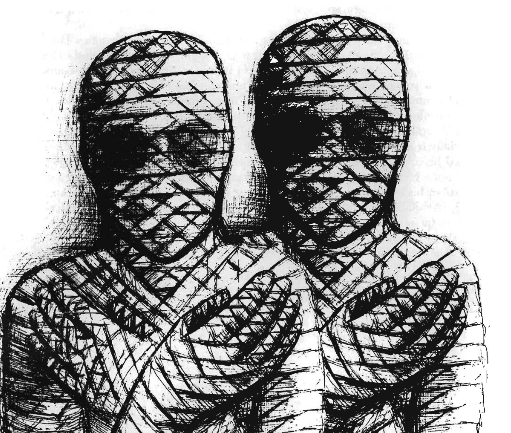

This account tells us, at least, that the two mummies were displayed side by side in a glass topped case, not in sarcophagi or even coffins; it does not suggest that papyri or accoutrements of any kind were displayed with the mummies.

More than a month later the last known newspaper reference to the mummies in the Chicago museum appeared on October 26 in the Chicago Times: “There, too, are the mummies, horribly shriveled things. … ” Both these accounts reinforce many other accounts that the missing Mormon mummies are hardly objects of art, hardly likely to be prominently displayed anywhere today should they still be in existence.

As Wyman in Saint Louis did not maintain possession of the mummies for long, neither did the original Chicago buyers. By January 1864, they had sold out to the flamboyant Joseph H. Wood, the “P. T. Barnum of the West.” While Bates and Wyman in Saint Louis had been serious museum operators, Wood was strictly a showman, not above hokum and sensationalism.

Although Wood was generally in possession of the mummies from 1863 to 1871, little is known of him.[10] Apparently he got his start in show business in Cincinnati in 1850 when he opened “Wood’s Cincinnati Museum.”[11] After his museum burned in 1851, Wood commenced touring with a collection of human curiosities. In Saint Louis in 1853, the Missouri Democrat of May 13 recorded his “serious intention of coming back to open a museum.” Instead, he opened a museum in 1854 on Dearborn Street in Chicago. He continued touring, however, returning to Saint Louis in 1856, ’57, and ’58. After Wood acquired the Chicago Museum he changed its name to Wood’s Museum and quickly expanded the collection, later claiming 300,000, even 500,000 curiosities. The Mormon mummies were increasingly overshadowed by more interesting exhibits and their presence is mentioned only three times. One is a Joseph Smith III letter stating he “saw two of the mummies and part of the records in Wood’s museum in Chicago where they were destroyed by the fire of 1871.”[12] The other is the 1869 Salt Lake City Directory which referred to Colonel Wood’s Museum and “the mummies around which the papyrus .. . on which the Book of Abraham was inscribed, from a collection as specimens worthy of the attention of all.”[13] Charles W. Penrose, enroute to a mission in England saw the “papyrus rolls” in the “Chicago Museum in 1865 . . . along with a statement by Chandler [from whom the Mormons acquired the mummies in 1835].”[14] Apparently the two mummies and whatever papyri were with them lay for years in an out of the way cabinet of Wood’s Museum, perhaps even in storage, until Sunday, 8 October 1871.

The fire, which broke out at 8:45 P.M. on the west side of Chicago had reached and jumped the Chicago River by midnight. Ninety minutes later, at 1:30 A.M., the fire lapped at Wood’s Museum and reduced it to brick and ash. According to the October 19 issue of the Chicago Tribune, “The only article spared from the immense collection of curiosities which were stored in Wood’s Museum is a silver mounted revolver. . . .” With a showman’s jaunty resilience, Wood placed a sign on his smoldering building, “Col. Wood’s Museum, Standing Room Only.”[15]

Everything points to the fact that the two mummies and papyri were incinerated shortly after midnight on 9/10 October 1871. But many, including myself, hope that providence would not have permitted that to have happened. What alternatives are there? Not many. A close study of maps of the 2,124 acres and 17,450 buildings burned by the fire suggests strongly that almost any other logical place the mummies could have been was also destroyed by the fire.

Wood might conceivably have sold or lent some of his Mormon Egyptiana to the Chicago Historical Society located at Ontario and Dearborn Streets; but according to the Chicago Strangers and Tourists Guide of 1866 this society possessed about 80,000 books, manuscripts, letters, documents, charts, maps, medals, and photographs, but no Egyptian items. In any event this collection was burned in 1871. Wood might also have sold something to the Chicago Academy of Science (founded 1878 and later the Field Museum) at LaSalle and Randolph Streets. The same Guide, however, informs us that the academy had over 40,000 specimens of natural science but mentions no mummies. It too was destroyed by the Chicago fire.

But suppose they were not destroyed. Why is there no reference to these mummies ever again in Chicago? Surely Wood would have put them back on exhibit. Alas, a study of mummies mentioned in Chicago between 1871 and 1982 reveals no Mormon connection.

To begin with, there is no evidence of mummies proir to 1863. In fact, there may have been no museums in Chicago before 1863 except for a short lived Western Museum in 1845, and than the museums of Wood in 1854 and 1859. The Chicago Times of 22 August 1863 reported, “The establishment of a museum in Chicago has long been talked about, but has heretofore been thought impossible.” Between the Great Fire and 1892 there were several museums in Chicago. The most important were apparently the Libby Prison Museum, the Eden Museum, Epstean’s New Dime Museum, Kohl & Middle ton’s South Side Museum, Kohl & Middleton’s West Side Museum, the W. C. Coup and Uffner’s Museum, and the Great Chicago Museum which housed the Worth collection. This latter museum is the only one that seems to have exhibited an Egyptian mummy. Its 1885 catalog claims “the only stripped mummy on the continent, the wrapping, some hundred yards of linen, being entirely removed. In this specimen the hair, eye-lashes, teeth and nails are re markably perfect. The scarabee or beetle placed over the left eye of the mummy by its owner contains the name Amon. . . .”[16]

The hoopla about the “stripped” condition of the mummy strikes one as hokum to disguise the lack of interesting or expensive accoutrements. The very plainness may remind one of the Mormon mummies, but the scarab sug gests that it was not.

Unfortunately, the Chicago Historical Society has been unable to discover any further information about the provenance or later disposition of Worth’s mummy. Worth himself seems to have been a wealthy dilettante with a collecting mania. The Great Chicago Museum was not listed in Flinn’s 1891 The Standard Guide to Chicago.

After 1892 quite a few Egyptian antiquities appear in Chicago. The Field Museuem opened in 1893 and now houses thirty-four mummies and other Egyptian antiquities obtained between 1893 and 1924. Almost all of them, according to their accession records, were purchased in Egypt. In 1894 the Oriental Institute was founded and by the 1920s had six mummies and other Egyptian antiquities. In 1923 the Art Institute of Chicago acquired one female mummy, three coffins, one mummy case, one limestone head, three mummy and four canopic jars, most of which were later sold to the Oriental Institute.

During the 1920s, a certain John Guenther of Chicago owned a mummy, and during the 1850s, Garrett Seminary had one or more Egyptian coffins of the Roman period, but no longer.[17] According to all available information, especially accession records, none of these antiquities have any connection with those once owned by Joseph Smith.

If Wood had sold, traded, or leased his two mummies to someone outside Chicago before the fire, where might they be? By 1871 there were at least seventy-six recognized museums in the United States and dozens of private col lections. To date I have discovered no link between such collections and Wood’s.

III

Let us now turn our attention to Philadelphia. At least thirty years ago someone, possibly James Haggerty or James R. Clark, noticed a story in the San Francisco Bulletin of 25 September 1857: “About a year since, Mr. Wyman of the Philadelphia Museum, purchased two mummies: one of each sex, from a gentleman who had purchased them directly from the widow of Joe Smith. . . .” This story, attributed to the Philadelphia Sun, has wasted the time of a generation of Mormon scholars in a vain search for Wyman. I am only the last in a long line to have chased this wild goose.

To explain this alleged Philadelphia connection, let me refer again to the Missouri Democrat story of 13 May 1857 describing the facsimiles. This Saint Louis story is identical in every detail with the San Francisco Bulletin, except for the addition of the words “of the Philadelphia Museum.” The San Fran cisco editor or reporter apparently confused the origin of the story, crediting the report to Philadelphia rather than Saint Louis. Many, including myself, have searched the Philadelphia Sun in vain for “Jo. Smith’s Mummies.” We have not found it for the very good reason that it never was there. There was, in fact, no Philadelphia Museum in 1856 or 1857 and only six Wymans. The only one possibly connected with some museum was John Wyman, artist and ventriloquist. The Mormon mummies were indeed in Philadelphia but in 1833, a fact of no value to this study.[18]

What other mummies have been in Philadelphia? There have been museums in Philadelphia since at least Charles Wilson Peal’s in 1784, but very few exhibited mummies. Perhaps the first to do so was George R. Gliddon’s Chinese Museum in the early 1850s, whose “Panorama of the Nile” had some Egyptian mummies. This museum had burned by 1856.[19] In 1858, the European Museum which had one “hydrocephalic” female mummy,[20] and P. T. Barnum himself operated a museum in Philadelphia from 1842 until it burned in December 1851.

In more recent times there have been other mummies in Philadelphia. When Colonel Wood moved from Chicago to Philadelphia in 1873 and opened his museum at the corner of Ninth and Arch Streets he advertised “Mummies, Petrified Human Body,” among other curiosities.[21] Since the mummies in Saint Louis and Chicago were always identified as Egyptian, Wood’s Philadelphia mummies may have been Indian. At least there is no further evidence he exhibited any from Egypt.

Egyptian mummies have also been exhibited in Philadelphia at the Academy of Natural Science, the Pennsylvania Museum of Art, and at the University of Pennsylvania museum; but there is no indication of any connection between these mummies and those once owned by the Mormons.

One additional bit of fascinating Philadelphia esoterica is the 1977 discovery at the Academy of Natural Science of two lost and forgotten mummies behind a false wall. As of 1982, no one at the academy has a clear idea of the provenance or the date of acquisition of these two mummies although there is a vague impression that the museum acquired them in 1856. However, 1856 is the crucial year. If the agent, A. Combs, who bought the mummies in Nauvoo on 26 May 1856, and sold two in August of the same year in Saint Louis, continued down the Mississippi and up the Ohio he might very well have eventually reached Philadelphia and sold the remaining two to the Academy.

However, it is not a likely hypothesis. Photographs of the mummies show them well wrapped and in rich sarcophagi.[22] It is my equally unsupported hypothesis that the story involving 1856 was generated by Mormon students, like Whipple and myself, pestering the Academy for evidence to back up the story incorrectly attributed to the Philadelphia Sun.

IV

Ransacking Saint Louis and Chicago turned up little, and I have just shot down the Philadelphia Story. Somehow this alone did not seem important enough for publication. So, having struck out like everyone else in the post 1856 period, I decided to busy myself in the pre-1856 world looking for some hints which might give rise to some fresh ideas regarding the missing Mormon Mummy Mystery. In so doing I quickly entered the murkiest chapter in all Mormon history, namely “Illinois Mormons, 1846-60.”

Let us go back to 26 May 1856, and work backwards. The bill of sale, dis covered with the eleven pieces of Mormon Egyptian papyri in the Metropolitan Museum in New York City in 1966, reads:

Nauvoo City May 25/56

This certifies that we have sold to; Mr. A Combs four Egyptian Mummies with the records of them. These Mummies were obtained from the catacombs of Egypt sixty feet below the surface of the Earth, by the antiquarian society of Paris & for warded to New York & purchased by the Mormon Prophet Joseph Smith at the price of twenty four hundred dollars in the year Eighteen hundred thirty-five they were highly prized by Mr. Smith on account of the importance which attached to the records which were accidentally found enclosed in the breast of one of the Mummies. From translation by Mr. Smith of the Records these Mummies were found to be the family of Pharo King of Egypt. They were kept exclusively by Mr. Smith until his death & since, by the Mother of Mr. Smith notwithstanding we have had repeated offers to purchase which have invariably been refused until her death which occurred on the fourteenth of this month.

Nauvoo L.C. Bidamon

Hancock Co. Ill May 26 Emma Bidamon: former wife of Jos. Smith

The fact that this bill of sale had been published by the Daily Missouri Democrat in June 1857 suggests that Combs gave copies of his original bill of sale to whomever purchased his Mormon Egyptiana. If researchers could ever turn up another reprinting of this bill of sale, we would know what happened to the two mummies and papyri Combs did not sell in Saint Louis.[23]

The Prophet’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, earned a modest sum exhibiting the Egyptian antiquities during the Illinois period of Church history up until September 1846 when most of the Smith family quit Nauvoo for safety’s sake. Lucy went with her daughter Lucy Smith Milikan north to Knox County taking the mummies and papyri with her. There is no evidence that she possessed or exhibited the mummies after she left Knox County during the spring of 1847, eventually returning to Nauvoo to live with her daughter-in-law, Emma Smith Bidamon.[24] An equally careful search of Emma’s life for the same period has turned up no hard evidence that the Mormon antiquities returned to Nauvoo prior to their sale in 1856.[25]

However, another member of the Smith family, the Prophet’s brother William, is more important to the issue. Also, tracking William around Illinois and elsewhere between the flight of September 1846 and 1856, corresponding with scores of scholars and institutions, visiting court houses, and reading miles of newspapers on microfilm was a bit more rewarding. During this period he seems to have been quite unstable, conducting unsuccessful attempts to establish himself as either his brother’s successor, or as an apostle or patriarch with one faction or another. (Only years later did he finally ally himself with his nephew, Joseph Smith, III in the Reorganization.)[26] He may have been the last person to have possessed the mummies and papyri before their sale in 1856 and seemed to think the mummies would strengthen his claim to leadership among the Mormons who did not follow Brigham Young west.

He apparently exhibited them for prestige and profit. In a letter to Brig ham Young, written from Nauvoo, 31 January 1848, for example, Almon W. Babbitt wrote, “William has got the mummies from Mother Smith and refuses to give them up.”[27] Prior to acquiring the mummies from his mother by un known means, William had on 2 December 1846, written James J. Strang, one of several who claimed the “mantle of Joseph,” that “the mummies and records [papyri] are safe.” Later that same month, on December 19, William in formed Strang “the mummies and records are with us and will be of benefit to the Church [when?] we can get them to Voree, [Wisconsin].”[28]

The evidence that William traveled and exhibited the mummies is tantalizingly vague and slender. I assumed that the local press of western and northern Illinois would have surely picked up and reported on anything as outre as the brother of the martyred Mormon Prophet, Joseph Smith, exhibiting mummies and papyri. I read every extant issue of every newspaper published between 1846 and 1856 in thirty-four counties of western and northern Illinois, and found no reference to the mummies, even though mummies made esoteric fillers and we learn, for example, from the 1848 Aurora Beacon that there were mummies in Mexico, from the 1853 Quincy Herald that Arabs used them for firewood, and from the 1856 Dekalb County Republican Sentinel that Egyptians used them for fuel.

Although neglect in the press was total, Newton Bateman’s History of Kendall County gives the “Recollections” of George M. Hollenback, born in 1831, who had met Mormon Missionaries in his father’s house:

Emma Smith, the widow of Prophet Smith, had. . . . four Egyptian mummies and the papyrus manuscript that accompanied them. These manuscripts were preserved in the cabinet of drawers covered with glass. The mummies were placed in oblong boxes, a little longer than the height of a person near six feet. A curtain from about the middle of each extended to the feet and was secured so that it would not fall. Mrs. Smith’s nephew, by the name of Bennett, procured these specimens of Egyptian civilization of some thousands of years ago for the purpose of exhibiting them, I presume, for money. As he had stopped at my father’s house a few times in passing back and forth, he stopped again with his grewsome [sic] load. As it was nearly noon, he was persuaded to bring his “goods” into the house and set them in the spare room. He consented that the school children from the school house near by could come in and view the “remains,” which they all did, boys and girls, and it did not cost them a cent. From that day to this we have never heard a single word from Bennett and his mummies. I have neglected to state in its proper connection, that each mummy was encased or swathed in very many yards of the finest linen.[29]

His description of the cabinet of drawers and oblong boxes adds a little to what we already knew from other sources, and the reference to stopping “a few times in passing back and forth” suggests more than one exhibition tour. The reference to Mrs. Smith’s nephew Bennett seems to be a mistake for William, and Hollenback’s statement that the mummies were swathed does not match other accounts describing the mummies as unwrapped. Certainly by the time two of these mummies were exhibited in Saint Louis and Chicago they were no longer swathed.

This recollection is hardly the complete story, but William, who moved around a great deal in the 1850s, probably stored or hid the antiquities for some future use. William was seldom gainfully employed, was often in financial straits, and owned very little. For example, when he was fined $25 in an 1848 assault case, the Lee County sheriff reported to the court his inability to find “any goods or chattels of the said William Smith whereof I may by distress and sale levy the sum of twenty-five dollars fine.”[30]

Furthermore during 1849 and 1854, while residing in or near what would later be Amboy, Lee County, William was also involved in a lurid divorce case with Roxey Ann Grant Smith, and indicted for adultery, fornication with Rosa Hook, bastardy, and rape as well.[31] Although the cases of assault, rape, and fornication were eventually dismissed and the bastardy (or paternity) case was moved to another court on an order for a change of venue, his legal expenses for defense were considerable.[32] Moreover, the court granted Roxey Ann the divorce on grounds of desertion and William had to pay all court fees and expenses.[33] In addition to all these expenses he was required in 1854 to post $1,000.00 bail on the rape charge.

During these dark days of spring 1854, William jumped bail and fled to “somewhere on the Illinois River.” From there he wrote asking legal help from a lawyer friend in Lee County. The lawyer required a retainer of $50 which William could not raise.[34] William continued his flight to Saint Louis where he was apprehended, returned to Dixon, and jailed.[35] Lee County rumor had it that William had gone to Saint Louis en route to asylum in Utah.[36]

The relevance of William’s personal life at this point is the question of money. If he could not raise even $50 for his own defense, by the spring of 1854, where did he secure the money to live on after jumping bail, the money to go to Saint Louis, and to even allegedly contemplate going to Utah? I hypothesize that during these trying times William sold or leased the Egyptian antiquities, possibly while a fugitive on the Illinois River. To whom could William have sold or leased mummies and papyri? The strange world of show men, hokum, showboats, exhibitors, popular museums, and the circus offers intriguing possibilities. Apparently it was a small world. The few men in this select fraternity all exhibited mummies at one time or another and seemed to have associated with each other. Barnum visited Wyman in 1851 and Wood in 1866; Wood was in Philadelphia and probably visited Wyman in Saint Louis during the mid-1850s; Koch lectured for Wood in Chicago in 1863. The “Mormon mummies” may well have been the subject of conversation. William may have sold or leased the antiquities to one of the many circuses playing along the Illinois River. The local press included 134 references to twenty-eight different circuses playing this area of Illinois during 1848-56, some featuring “Museums of Wonder.”[37]

Thus, I tentatively conclude that A. Combs, who bought and sold the Mormon Egyptiana was much more likely to have been associated with circus people than to have been a freelance buyer of curiosities for museums and collectors. Since some of these circuses which toured the upper Mississippi and Illinois rivers also played Saint Louis, this could explain how two of the mummies ended up in Saint Louis. The Floating Palace, which featured a reported “100,000 curiosities,” some from Egypt, was the likely candidate to have purchased the mummies.[38]

Meanwhile, A. Combs remains unidentified despite searches in Illinois newspapers, correspondence with circus scholars and circus museums all over the United States, the Saint Louis city directories, Missouri or Illinois census records, dozens of historical societies, and collections of the Utah Genealogy Society. I still don’t even know his first name. This shadowy figure has sur faced nowhere.

There is a further question: How did Combs get a bill of sale from the Smiths in Nauvoo on 26 May 1856 if William had previously sold them else where? A possible answer may be that William rented, leased, or sold all or part of the antiquities under circumstances that precluded concluding the transaction until the death of his mother to whom the mummies and papyri legally belonged. For the record, Combs arrived in Nauvoo only ten days after her demise. Furthermore, in 1898 William’s nephew, Joseph Smith III, stated in a letter:

We learned that while living near Galesburg [Knox County], Uncle William undertook a lecturing tour, and secured the mummies and case of records, as the papyrus was called, as an exhibit and aid to making his lectures more attractive and lucrative. Uncle William became stranded somewhere along the Illinois River, and sold the mummies and the records with the understanding that he might repurchase them. This he never did . . . Uncle William never accounted for the sale he made, except to state that he was obliged to sell them, but fully intended to repurchase them, but he was never able. . . .”[39]

While this statement provides corroboration for my thesis, it raises the question of how Joseph Smith III, who in 1856 signed the bill of sale, could forty-two years later in 1898 state that his uncle had sold them prior to 1856? Was his memory faulty? Perhaps. I am not the first to wrestle with this problem. Let us take a closer look, however, at one word and one phrase in young Joseph’s account. The word “obliged” seems to echo William’s financial exigencies which and the phrase “with the understanding that he might repurchase them” clearly indicates that William’s transaction, whatever it was, was not final. Could this phrase explain why Combs showed up in Nauvoo on 17 May 1856 to finalize this unusual deal with William, a deal somehow connected to the death of his mother, Lucy Mack, to formalize and legalize a sale which had already been effected two years previously?

There remains a final question. If perchance Providence saved the Egyptiana, if the antiquities were not incinerated in Chicago, or in other fires (Barnum, who bought up hundreds of small collections, was burnt out in 1851, 1865, 1868, 1872, and 1887), if the mummies were not powdered into aphrodisiacs or shredded into paper pulp, where might they be today? In 1968 Walter Whipple eliminated over fifty museums. My own research has eliminated 150 additional art and historical institutions.[40] If they indeed exist, they are probably in storage, unknown, unidentified, and forgotten.

Would the papyri be with them? Probably not. The eleven pieces dis covered in 1966 were separate. Nor would we be likely to recognize the missing papyri if we found them unless Facsimile No. 2 or 3 was among them. There are certainly rumors aplenty to check out — at one time someone is supposed to have offered the Mormon papyri to some school in Chicago and the Mor mons were not “supposed to find out about it,” some minister in Texas is supposed to have some papyri which the “Mormons will never get,” in 1878 President John Tayor was supposed to have sent Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith to Chicago to obtain the antiquities from Wood if possible; there is also the allegation that the antiquities were divided into four portions. If so, William might have sold only one portion and apparently it was the same portion which was discovered in 1966. This rumor is linked to another supposition that when Lucy and Emma discovered that they did not have the Book of Abraham papyri they sold what they had for what they could get. Furthermore, as noted above, someone allegedly saw one of “our mummies” in Saint Louis in 1950, others claim to have seen them in Chicago in the 1860s.

The air is now heavy with one portentious question — “So what?” As one scholar wrote, “I find your paper an exhilarating tour-de-force . . . but why did you do it?”

A fair question and my brief answer is: For one thing I am a workaholic stuck in the Midwest, for another it was great fun, and maybe I narrowed the direction of future research efforts from 360 degrees to, say, 90 degrees, but most importantly, I am convinced that it is a good, though not very rewarding cause. Perhaps the best that can be said of it is that no one else ever needs to do it.

[1] James R. Clark, The Story of the Pearl of Great Price (Salt Lake City, Utah: Book craft, 1955) ; Walter L. Whipple, “The St. Louis Museum of the 1850s and the Two Egyptian Mummies and Papyri,” BYU Studies, 10 (Autumn 1969) : 57-64; Jay M. Todd, The Saga of the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, 1969).

[2] Missouri-Democrat, 22 Jan. 1857. The article specifically adds that he was “no Barnum.” The 1863 Guide to the Chicago Museum declares that Bates “has devoted his life, with the enthusiasm of an artist, to this branch of [natural] science and now stands without fear of rivalry, at least in America, . . . He has made frequent journeys to Europe, South America and the tropical regions, in order to obtain the best and rarest birds and quadrupeds which these continents afford.” A Guide to the Chicago Museum (Chicago, 111.: 1863), p. 3.

[3] Seyffarth’s Nachldsse are at the Concordia Seminary, Saint Louis, and in the Brooklyn Museum in New York City. His lectures on Egypt appeared in the St. Louis Leader, 26 Nov. 1856; Evening News, 29 Nov. 1856; The Missouri Democrat, 29 Nov. 1856; and the Saint

Louiser Volksblatt, 23, 25, 29 Nov. 1856, and 27 Feb. 1857. Although Seyffarth published at least twelve articles in the Transactions of the Academy of St. Louis between 1857 and 1860 on astronomy, inscriptions, an Assyrian brick, a mummy in Paris, a papyrus scroll in Massachusetts, and related topics, he never again referred to the Egyptiana in Saint Louis.

[4] The 1856 catalogue of the Saint Louis Museum states: “These Mummies were obtained in the Catacombs of Egypt, sixty feet below the surface of the earth, for the Antiquarian Society of Paris, forwarded to New York, and there purchased, in the year 1835, by Joe Smith, the Mormon Prophet, on account of the writings found in the chest of one of them, and which he pretended to translate, as stating them to belong to the family of the Pharaohs’. . . . They were kept by the Prophet’s mother, until her death, when the heirs sold them. Catalog of The Saint Louis Museum (Saint Louis, Mo.: 1856) n.p. Copy in Missouri Historical Society, Saint Louis, Missouri. I have found no contemporary reference to the mummies in the journals of many Mormons who passed through Saint Louis on their way west or who lived there during the 1850s. The Saint Louis Church records of that time are equally barren as is the Mormon newspaper, The St. Louis Illuminator of 1854-57.

[5] See Daily Evening Gazett, 7 March 1844; John Thomas Scharf, History of St. Louis and County (Philadelphia, Perm.: L. H. Everts, 1883), pp. 982-83; John Francis Mc Dermott, “Museums in Early St. Louis,” Missouri Historical Society Bulletin, 4 (Jan. 1948) : 129-38; and his “Dr. Koch’s Wonderful Fossils,” Missouri Historical Society Bulletin (July 1948) : 233-56. Dr. Joseph N. McDowell of Saint Louis added a small collection of curiosities to his medical college; and while he exhibited no Egyptiana, he did possess another Mormon-related item, the infamous Kinderhook Plates which Joseph Smith was supposed to have translated. See my “Kinderhook Plates,” Ensign 10 (August 1981) : 66-74.

[6] Correspondence with the Department of Anatomy, School of Medicine of Washington University at Saint Louis, 14 Sept. 1972; Saint Louis Art Museum; also the Saint Louis Museum of Science, and Washington University Gallery of Art, 24 Aug. 1972.

[7] The Academy of Science in Saint Louis, just the year before Wyman lost his museum, had tried in vain to raise $10,000 to buy Wyman out. Had they succeeded, perhaps the mummies and papyri would still be in Saint Louis. Disappointingly, the archives of the Saint Louis Academy shed no further light on the Mormon mummies.

[8] On August 8 the Chicago Evening Journal added that “it contained over 50,000 rare specimens of beasts, birds, reptiles, insects, fossils, etc.” The Chicago Evening Journal of 7 July and the Chicago Times of 8 July made similar statements. The Chicago press published only about two more stories in 1863 and none, as far as I can tell, thereafter. Interest continued in Egyptian antiquities. On 8 April 1865, for example, the Chicago Times announced, “A free lecture on Ancient Egypt will be given in Unity Church,” and on 9 Nov. 1870, the Chicago Evening Journal reported that a mummy was being exhibited in the Crystal Palace in London. There was no reference to the mummies in Chicago or references to these mummies in the many contemporary guides and directories in Chicago still extant.

[9] See E. Boswinkel and P. W. Pestman, Textes Grecs, Demotiques et Bilingues (Holland, E. J. Brill, 1978), pp. 232-59, plus plates. The Oriental Institute of Chicago has five mummy tablets.

[10] See Allen Cooper, “Colonel Wood’s Museum: A Study in the Development of the Early Chicago Stage” (M.A. thesis, Roosevelt University, Chicago, 1974) ; Robert L. Sher man, “Chicago Stage” (Chicago, 111.: Robert L. Sherman, 1947) ; Chicago: A Strangers and Tourists Guide (Chicago: Religious Philosophical Publishing Association, 1866), pp. 98-99; A. T. Andreas, History of Chicago (Chicago: A. J. Andreus, 1884), pp. 607-609. William S. Walker, The Chicago Stage (Chicago, 111.: William S. Walker, 1871), pp. 50-51. See also the extensive collection of handbills and theater programs at the Chicago Historical Society, and Joseph Jackson, Encyclopaedia of Philadelphia (Harrisburg, 1932), p. 917 and an 1873 handbill in the Theatre Collection of the Library of Philadelphia pertaining to Wood’s Museum.

During most of this eight-year period the museum was known as Wood’s Museum, but when one of Wood’s actors assumed its direction, it was known as Aiken’s Museum from October 1867 to March 1869 and from October 1869 to May 1871. Some sources refer to Aiken’s Museum as if it were a different museum altogether, which it was not.

[11] Knoxville (III.) Journal, The Public Library of Cincinnati to Stanley B. Kimball, 13 May 1851, 27 May 1982; and James F. Dunlap, “Sophisticates and Dupes: Cincinnati Audiences, 1851,” Bulletin of the Historical and Philosophy Society of Ohio, 13 (April 1955): 87-97.

[12] Joseph Smith III to Heman C. Smith, 24 Oct. 1898, Saint’s Herald 46 (11 Jan. 1899): 18.

[13] E. L. Sloan, compiler, Salt Lake City Directory and Business Guide for 1869 (Salt Lake City, Utah: 1869).

[14] Bikuben, 28 July, 1910. I wish to thank Richard Jensen for drawing this reference in a Utah-published Danish newspaper to my attention.

[15] With the showman’s instinct for survival, Wood immediately leased the Globe Theater, the only theater in Chicago left after the fire, and reopened the theater part of his operation in less than a week. About two years later, in 1873, however, he moved to Philadelphia and opened Col. Wood’s Museum Gallery of Fine Arts and Temple of Wonders. Another museum bearing the name of Wood reopened in Chicago in 1875 at 75 Monroe Street, but lasted only to 1877. Wood may have been managing it long distance for a Chicago City Directory of 1876 lists him along with the museum but noted he resided in Philadelphia. In 1884 Wood returned to Chicago, opened another museum on the same site as the old one, but sold it within the year to a Mr. Slanhope, who renamed the collection the Dime Museum. Wood is listed in Chicago directories until 1902.

[16] Great Chicago Museum Catalogue (Chicago: Blakely Marsh Printing Company, 1855), p. 20. Copy in the Chicago Historical Society.

[17] This information comes from many private conversations in the Chicago area.

[18] Prof. H. Donal Peterson of BYU has had a skull of one of these mummies in his office for some time. See the Newsletter and Proceedings of the Society of Early Historic Archae ology, May 1981, pp. 6—7. For some new, related research on the mummy problem see H. Donal Peterson, “Mummies and Manuscripts: An Update on the Lebolo-Chandler Story,” Eighth Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, Jan. 1980), pp. 280-92.

[19] Phillip Lapansky of The Library Company of Philadelphia to Stanley B. Kimball, 2 Feb. 1982; Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulletin, 9 July 1856.

[20] Descriptive Catalogue of the European Museum (Philadelphia , Perm.: European Museum, n.d.), p. 12, a xerox copy of which was sent to me by The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

[21] “Col. Wood’s Museum,” 9 June 1873. Museum Flyer, Theater Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.

[22] This appeared as a brief notice in Frontiers (Summer 1977), p. 50, published by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

[23] During this same crucial year, Wood was exhibiting “the Greatest Curiosities in the World” in Philadelphia during October 1856. On e could fantasize that Wood purchased the two remaining mummies from Combs or that a chance meeting with Combs in 1856 in Philadelphia encouraged Wood to buy the mummies when he found them on exhibit in Chicago in 1863. Unfortunately there is absolutely no evidence to support such conjectures. Wha t we do know is that Wood was then only exhibiting “huma n phenomenons [sic]”—living giants, midgets, fat ladies, and a baby with whiskers. Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulle tin, 8, 9, and 13 Oct. 1856. This bill of sale is the source for the description of the mummies and papyri which appeared in the Saint Louis and Chicago museum catalogs, thus the solution to another minor mystery.

[24] There are many accounts of Mormon and non-Mormons visiting Lucy Mack Smith between 1839 and 1845 to view the mummies and the papyri. Th e latest reference to “Mothe r Smith” keeping the mummies in Nauvoo which I have found comes from the Warsaw Signal, 10 Sept. 1845. In all the miles of microfilmed western and northern Illinois newspaper I read, the only reference to Lucy was a brief note of her death in May 1856. I found absolutely nothing in the press about her or anyone else exhibiting the mummies outside Nauvoo.

[25] There is very little available on the life of Emma Smith between September 1846 and 1856 pending the publication of the biography by Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippets Avery. Richard L. Anderson has “about two dozen” reports of people visiting Emma in Nauvoo during this period but they contain no reference to the mummies. Richard L. Ander son to Stanley B. Kimball, 4 March 1980.

If we can trust some very late after the fact memories, Jerusha Walker Blanchard re ported that as a child she played “hide and seek” with Emma’s sons and hid among the mummies in the Mansion House after Emma returned to Nauvoo, suggesting the mummies might have returned to Nauvoo for a season. Jerusha Walker Blanchard, as told to Nellie Stary Bean, “Reminiscence of the Grand-daughter of Hyrum Smith,” The Relief Society Magazine, Jan. 1922, pp. 8-9. I thank Irene Bates and Linda King Newell for drawing this to my attention.

[26] Sources on the life of William between 1846 and 1856 are about as scanty as those of his mother and sister-in-law. One should start with Calvin P. Rudd, “William Smith: Brother of the Prophet Joseph Smith” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1973.) Especially valuable is Irene M. Bates, “William Smith, 1811-93, Problematic Patriarch,” DIALOGUE: A JOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT 16 (Spring 1983) : 11-22.

[27] Journal History, 31 Jan. 1848, Historical Department Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; hereafter cited as LDS Church Archives.

[28] Copies of these letters in the Milo M. Quaife Collection of the University of Uta h Library wer e kindly provided by Richard L. Anderson of BYU. See also related letters in the Voree Herald, 11 Marc h and 11 M a y 1846, Zion’s Reveille, 10 Feb. 1847, the Chronicles of Voree, 6 April 1847, and Milo M. Quaife, The Kingdom of St. James . . . (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1930), p. 30.

[29] I wish to thank Mrs. Richard Wildermuth of Piano, 111., for drawing this unique find to my attention. Illinois newspaper editors for the period 1847-56 showed a healthy interest in the Mormons in Utah, Iowa, Saint Louis, New Orleans, New York City, Kansas, Texas, California, England, France, Norway, Denmark, Ireland, Prussia, the Sandwich Islands, and Calcutta. They printed reports on Mormon government in the West, attempts to achieve territorial government and statehood, emigration, the Mormon Trail, the Perpetual Emigration Fund, Indians, missionaries, Mormons who left Utah and returned to the East, the Salt Lake Temple, the Deseret Alphabet, Mormon publications, grasshoppers, polygamy, Brigham Young, and “female life among the Mormons.”

But they seem not to have recognized as Mormons those Saints who did not go west, and ran only a few stories about the Nauvoo Temple, William Smith, James J. Strang, the Icarians, and one story about the destruction of some property once belonging to Joseph Smith.

[30] Lee County Criminal Court Records, Court House, Dixon, Illinois, General number 111, Term 1849, Record B, p. 82. In the Court documents filed by William and Roxey Ann Grant Smith, Roxey describes his property as “an old leather trunk” which “contained a few old books such as an ‘old blessing book’ used by the father of the said complaintant, an old dictionary, some old Hymn books, a memorandum book kept by said complaintant of some of his public acts, and a few old weekly newspapers, a letter from a female in St. Louis requesting the said complaintant to send her the money he had promised, and two or three other letters from females in the East . . . written in a very endearing language.” William Smith and Roxey Ann Smith; Defendant’s answer, filed 11 May 1852, April Term, Knox County Circuit Court, 1852.

William described his property as “a trunk containing a large quantity of books, & the records, journals and proceedings of Th e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints . . . which said records, books and journals & proceedings belonged in part to said Church . . . the value of which . . . amounted to at least the sum of five thousand dollars.” Bills of Divorcement, William Smith vs. Roxey Ann Smith, filed 20 Nov. 1850, April Term, Lee County Circuit Court, 1850. Since the Mormons almost always referred to the papyri as “the records,” they may have been included in this old trunk.

[31] See the following Lee County Circuit Court Records at Dixon, Illinois. The Chancery File records of these cases are in the Lee County Circuit Court Clerk’s office and the Criminal File records are at the Illinois Regional Archives, Dekalb, 111. April Term, 1853, Chancery Book A, pp. 11, 21 ; Chancery Book B, p. 246; Criminal Book B, p. 348; Sept. Term, 1853, Criminal Book B, p. 388 ; April Term, 1854, Criminal Book B, pp. 459-60 ; Sept. Term, 1854, Criminal Book B, p. 466. See also the Dixon Telegraph, 9 April 1853, 30 April 1853, and 9 March 1854.

[32] I have been unable to determine the court to which this case was moved.

[33] Final Decree, Bill of Divorce, Roxey Ann Smith vs. William Smith, 26 April 1853, April Term, Knox County Circuit Court Record, Galesburg, 111. Most of William’s troubles at this time seem to have stemmed from his involvement in polygamy and from vindictive parties in various Mormon factions. Several letters appeared in the Dixon Telegraph in defense of William. On 30 April 1853 Rosa A. Hook signed a statement clearing William of wrongdoing and Aaron Hook claimed that a “girl was induced to slander William for money.” On 7 May 1853 an unprinted “letter from Cincinatti’ was said to defend William.

[34] Dixon Telegraph, 9 Marc h 1854.

[35] Ibid., 4 May 1854. The Missouri Republican 26 April 1854, reported this arrest: “IMPORTANT ARREST. On last Tuesday the sheriff of Lee Co., Illinois arrived in this city in pursuit of William Smith, a fugitive from justice. Smith, it appears was committed to jail in Hancock Co., Illinois some time since, on a charge of highway robbery, and sub sequently broke jail and went to Lee County where, after staying sometime, he became acquainted with two young ladies, sisters, and accomplished their ruin, after which he fled to this city. The sheriff, in the company of Officers Grant and Guion, after a search, arrested Smith yesterday at a house on Market St. between seventh and eighth, and he was taken back into custody of the sheriff. Smith is a large and powerfully built man, with good manners, and about 45 years of age.”

The St. Louis Daily Evening News, the St. Louis Intelligencer and the Belleville Tribune repeated the story with minor variations. The charge of highway robbery is incorrect. Refer ence to William’s faith is missing.

[36] Dixon Telegraph, 4 May 1854.

[37] Mummies had been exhibited since at least 1816 in Boston. I n 1853 Barnum’s traveling Museum of Wonders featured one.

[38] The famous Floating Palace (built Cincinnati, 1851), was towed by the James Raymond up and down the Allegheny, Wabash, Ohio, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers. Off the main circus area was a museum of “Curiosities and Wonders ” exhibiting “100,000 curiosities,” including some from Egypt. It sometimes played Saint Louis and we know from the St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican of 4 August 1856 that the Floating Palace was there about the time Combs was selling two mummies to Wyman’s Museum.

[39] Joseph Smith III to Herman C. Smith, 24 Oct. 1898, in Saint’s Herald, 46 (11 Jan. 1899): 18.

[40] Whipple was kind enough to lend me his entire file of his extensive research. I wrote to more than thirty universities and colleges founded before 1856, more than thirty museums which existed before 1859, more than thirty historical societies in nearby Iowa, sixteen museums in Philadelphia, seven circus museums, and forty-two historical societies in Illinois. I even ran a classified ad in the 1982 April issue of Aviso, the monthly newsletter of the American Association of Museums. From these societies I received no significant information and from the ad not one response.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue