Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 3

Of Prophets and Pale Horses: Joseph Smith, Benjamin West, and the American Millenarian Tradition

On 15 June 1844 Joseph Smith recorded in his journal that “[the steam boat] Maid of Iowa come [sic] down the river about 2 or 3 o’clock While I was examining Benj[amin] Wests painting of Death on the Pale Horse which has been exhibiting in my reading room for 3 days.”[1] This brief, passing entry is one of many which record Smith’s daily cultural interactions. The significance of this particular incident is that West’s apocalyptic Death on the Pale Horse found an audience among one of America’s eminent millenarian groups.

West’s picture has long been discussed in the context of British apocalypticism, and, although it was met with some ambivalence at its American debut in 1836, it may have been viewed with some appreciation from American millenarian sects such as Mormonism. As historian J. F. C. Harrison has stated, “It is difficult to estimate the impact that such pictures made,” but the art of romantic painters “echoed the warnings of millenarian writers” and were indeed an aspect of the “sub-culture” of millenarianism.[2] One author has maintained that the apocalyptic nature of nineteenth-century romantic art was principally a British phenomenon, saying “no such development occurred outside of England.”[3] While it is true that British painters initiated apocalyptic art beginning from the late eighteenth century, it does not lessen the potential appeal of such work among American millennialists.

As Ernest R. Sandeen has written, “America in the early nineteenth century was drunk on the millennium.”[4] Millennial discourse in America began with such colonial writers as Rev. John Cotton, The Churches Resurrection , or the Opening of the Fifth and Sixth Verses of the 20th Chapter of the Revelation (Boston, 1642); Thomas Parker, The Visions and Prophecies of Daniel Expounded (Newberry, 1646); and Jonathan Edwards, An Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Vision Union of Goďs People . . . (Boston, 1747). The common belief associated with all was the eminent consummation of the world, the Second Advent and millennial era – a period of one thousand years during which Satan will be bound and peace will prevail on the earth. Some differ as to whether Jesus Christ’s return was to precede or follow the Millennium, dividing them into two groups – premillennialists and postmillennialists. Published literature usually involved the interpretation of prophetic biblical passages from the books Daniel and Revelation. Mid-nineteenth century millenarian writers included George Duffield’s Millenarianism Defended (New York, 1843) and George Junkin’s The Little Stone and the Great Image: or Lectures on the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse which Relate to These Latter Days until the Second Advent (Philadelphia, 1844). Many evolved into sects such as American Shakerism or United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, Mormonism, and the Millerites. Mormonism and Millerism, both conceived during the Great Revival of New York’s “burned-over district,” have become prosperous religious organizations known today as respectively, the Latter-day Saints and the Seventh-Day Adventists.[5]

It should be brought to bear at this point, however, that whether or not West had any proclivity toward millennialism is inconclusive. Yet a reasonable connection can be inferred from West’s associations with American millenarian figures. John Gait, West’s official biographer, can now be discounted in his long-held myth that West was a practicing Quaker by birth.[6] While Quakerism may not have influenced his early work, other religious mentors played a part in the young painter’s life. West’s initial interest in art can be attributed to William Williams, but work completed between about 1754 and 1755 can claim influence from a German-born Moravian, John Valentine Haidt, who painted New Testament subjects described as “complex narratives filled with religious passion and intensity.” American educator and statesman Rev. William Smith was said to have encouraged West toward spiritual pursuits and introduced him to a study of “the ancients.”[7] Morton Paley, although he places West in the realm of British millenarian practitioners, has linked West with members of a millenarian circle headed by Rev. Jacob Duche from Pennsylvania.[8] Other members of this group included the painter P. J. de Loutherbourg, the sculptor John Flaxman, and the American engraver William Sharp.[9] That West did have some association with this group is evidenced by the fact that Thomas Spence Duche, Jacob’s son, was one of West’s American students,[10] as well as the fact that Duche’s two-volume Discourses on Various Subjects (1799) contained frontispieces by Sharp after paintings by West. This association, Paley suggests, may account for West’s “surge of activity on apocalyptic subjects” between 1796-1804. Paley then concludes that William Beckford, “England’s wealthiest son,” became West’s patron “because of the artist’s success with apocalyptic subject matter.”[11]

Taken from the book of Revelation, West’s subject Death on the Pale Horse is a dreadful depiction of St. John’s vision of the opening of the five seals as described in the first eight verses of the sixth chapter. The central figure shown in all versions is the terrible figure of death, riding a pale horse, trampling all who stand in his path. Other riders appear to his right, mounted on red, white, and black horses. These riders appear to be assisting in the destruction, slaughtering their victims with a sword. In earlier versions, the central figure of death appears as a crowned skeleton, reminiscent of John Hamilton Mortimer’s work of the same subject.[12] One contemporary reviewer described the figure as “the King of Terrors himself, on his pale horse. On his head is a crown, denoting his sovereignty over all things.”[13] One cannot help but see the influence of Durer’s The Riders on the Four Horses from the Apocalypse (c. 1496). Another comparison has been made with the similar equestrian stances in Ruben’s Lion Hunt (c. 1615).[14]

Other commentaries have shed light on West’s influences of the time. The entire subject of West’s Pale Horse was discussed in a seven-page descriptive catalog by Gait and a 172-page booklet issued on the occasion of the exhibition in 1817 by William Carey.[15] Gait’s work contains descriptions and commentary which seem to have been dictated by the artist, but Carey’s text contains added insight not in Gait’s. Carey repeatedly refers to a biblical commentary by Moses Lowman, entitled A Paraphrase and Notes on the Revelation of St. John (London, 1737), suggesting that West was familiar with Lowman’s work and was inspired by his interpretation. A recent scholar, Grose Evans, has discussed the influence of Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime . . . (1757) on West’s work. Evans states that West employed the increasingly favorable “Dread Manner” whereby the terrible and magnificent could infuse astonishment and reverence within the viewer. With regard to West’s Pale Horse, Evans states: “so detailed is the parallel between West’s picture and Burke’s theory that one may assume a deliberate effort by West to incorporate as much of Burke’s ‘terrible sublime’ as possible in this one picture.”[16]

Several versions of West’s Pale Horse are extant. John Dillenberger has traced the history of seven versions attributed to West executed between 1783 and 1817.[17] An early sketch, housed in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City, appears to depict Death in pursuit of two adult figures and an infant as in the traditional renderings of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden.[18] This conceptual drawing was probably followed by a more developed pen and brown ink composition dated 1783, now located in the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Two other preparatory oil sketches, dated 1787 and 1802, are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[19] Another, dated 1796, which had once been part of Lord Egremont’s collection at the Petworth House, Sussex, England, and exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1802, is now at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The final 1817 version is at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

A related piece is in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Completed in 1804, The Destruction of the Beast and False Prophet was possibly intended as a study for the History of Revealed Religion in the Royal Chapel at Windsor.[20] Helmut von Erffa and Allen Staley have stated that “although it shows a different subject based on a different passage in the book of Revelation than West’s paintings of Death on the Pale Horse , there are nonetheless significant similarities in the imagery.”[21]

When the Petworth House version was exhibited in the Picture Gallery at the Paris Salon of September 1802, Joseph Farington noted in his diary that “many French Artists were viewing Mr. West’s picture and said, ‘the attempt was hardy & the only one of such a subject of difficulty that had succeeded since the time of Rubens.'”[22] Though Jacques Louis David was reported to have dismissed the painting as “a caricature of Rubens,” Napoleon, upon being introduced to West, spoke more favorably of his piece, saying that he “hoped he had found Paris agreeable and expressed his approbation of the merit of his picture.”[23]

Americans as well as Europeans have counted West’s Pale Horse, along with his Death of General Wolfe, 1770, and Christ Rejected, 1814, as one of his paintings most worthy of merit. In 1801 Washington Allston, who might be considered America’s laureate millennialist painter and equal to Britain’s apocalyptic visionary, John Martin,[24] wrote of West’s Pale Horse:

No fancy could have better conceived and no pencil more happily embodied the visions of sublimity, than he has in his inimitable picture from Revelation. Its subject is the opening of the seven seals; and a more sublime and awful picture I never beheld. It is impossible to conceive anything more terrible them death on the white horse; and I am certain no painter has exceeded Mr. West in <the expression of> fury horror and despair which he has represented in the surrounding figures.[25]

After West’s death in 1820, the Annual Register commented that the version of 1817 could “justly be considered as one of the finest productions of modern art/’ and that although West was approaching his eightieth year when the grand-scale piece was completed, he “had lost none of his powers either of hand or mind.”[26] American art patron and historian Allan Cunningham said of the painting:

In his “Death on the Pale Horse,” he has more than approached the masters and princes of the calling. It is indeed, irresistibly fearful to see the triumphant march of the terrific phantom, and the dissolution of all that earth is proud of beneath his tread. War and peace, sorrow and joy, youth and age, all who love and all who hate, seem planet-struck.[27]

When the painting arrived in New York Harbor on 12 February 1836 on board the packet ship Hannibal , the Weekly Register took note, saying, “[T]his picture has long been regarded as the chef d’oeuvre of our distinguished countryman. As Americans we feel proud that this great work of art is permanently to remain in this country, and as Philadelphians we are gratified that such a treasure has been added to the already large and valuable collection of works of arts belonging to one of our public institutions.”[28]

Its exhibition in America, however, was not without mixed reviews. In reference to this “truly sublime picture,” one critic for the New York Mirror stated that he “would not compare the hard-earned fame of West with the smooth and easy road to popularity of Martin. In the works of West, I find as daring and comprehensive compositions as Martin’s.” He further added, “this is a picture that strikes at first sight; but it must be seen again and again to be duly appreciated.”[29]

New York and Boston patrons did not view the painting with as much enthusiasm.[30] Art patronage in America was turning toward historical painting and pastoral images of an ordered landscape as icons of cultural refinement. Only two years previous, Allston’s Elijah in the Wilderness was received with similar disinterest. West’s Pale Horse , like Allston’s Elijah, was probably seen by Boston and New York audiences as an example of terrifying disorder often seen in romantic biblical art and a passing theme of taste among the urban elite.[31] On 12 April 1836 New York entrepreneur and diarist Philip Hone made note of the exhibition in his journal:

Mr. West’s great picture, “Death on the Pale Horse,” which was bought by the Philadelphia Academy for $8,000, has lately arrived in this city and is now exhibiting at the gallery of the academy of fine arts in Barclay Street. It is a great picture undoubtedly, and has some striking points, but I did not like it when I saw it in London nor do I like it any better now. . . . This was the last production, I believe, of the great American artist, painted after he was eighty years of age. It is a curious and interesting coincidence that in the room adjoining there is one by the venerable Col. Trumbull, a pupil of West, painted after he also was fourscore. The Colonel himself pointed out this circumstance to me with a natural degree of exhultation.[32]

Later, the New York Mirror reported that, “though seemingly controverted by the apathy of the citizens of New- York,” West’s Pale Horse was met with “the cordial concurrence” of Philadelphians who could appreciate good art when they saw it, adding,

No work of art has excited so much attention in Philadelphia, or caused so profound a feeling of admiration for the sublime talents of West, as this great effort of his genius. The citizens of Philadelphia have shown that although they might be allured to visit the exhibition of an immodest picture, by the ruse of calling it moral or scriptural, they are not backward when an opportunity is afforded for contemplating a great work, from a native land, which conveys the most salutary lessons to every reflecting mind. We wish we could have said the same of our own citizens.[33]

This mixed feeling for apocalyptic subjects may not have been so evident for millennial expectants. J. F. C. Harrison has recognized that, for at least millenarian believers, apocalyptic art and poetry was an important vehicle of inspiration and instruction.[34]

In the same manner as earlier Christian eschatologists, William Miller, a New England farmer, tackled the interpretation of prophetic visions of Daniel and St. John. Taking up an increasingly popular theme in the “Burned-over District,” Miller attracted a devout group of followers called “Millerites” or “adventists.” In 1836 Miller published a calculated prediction of the Second Advent.[35] The advent year was to be “on or before 1843,” but when the prophecy failed, Miller extended the calculation to the summer of 1844. The expectation for prophetic fulfillment urged Millerite believers to await in eager anticipation of the Lord’s coming.[36]

As with the teachings of their millenarian contemporaries, the doctrines of the gathering of Israel, the sudden return of Christ, and the establishment of a New Jerusalem comprised increasingly important factors in the widening appeal of Mormonism. Many of the British proselytes may have found something desirable in Mormon seekerist qualities or possibly messages of the final consummation, recalling apocalyptic theologians Robert Aitken, John Wroe, Robert Owen, and Edward Irving.[37]

It was interest in Miller’s prophecy, however, that elicited a flurry of Mormon polemics.[38] While Mormon rebuttals rarely addressed Miller’s calculations directly prior to 1843, their dogmatic language clearly refuted his claims from the time of his Lectures in 1836. As early as 1841 Mormon writings were defining a premillennial doctrine. The Mormon millennial doctrine included the personal reign of Christ, preceded by the final gathering of Israel, the binding of Satan, and the destruction of the wicked. On occasion, written expositions carried a terrifying, destructive posture not unlike the Burkean theory of the sublime.[39] A number of published articles attacked the Millerite formulaic predictions with fervor.[40] Millerism was a subject of discourse during the spring of 1843, when Joseph Smith and other church leaders addressed the subjects of the book of Revelation and the coming of “the Son of Man.” On 2 April 1843, in reference to John 1:1-3, Orson Hyde stated that “when he shall appear we shall be like him &c. he will appear on a white horse, as a warrior, & maybe we shall have some of the same spirit. – our god is a warrior.”[41] It was also during this period of commentary on St. John’s Revelation that Joseph Smith reportedly gave his disputed “White Horse Prophecy.”

The prophecy, first retold by Edwin Rushton and Theodore Turley about a decade after Smith’s death, alleges that Smith employed the apocalyptic language of John the Revelator, likening the church to the “White Horse of Peace and Safety” and the “Pale Horse” as the “people of the United States.” The prophecy also foretells the Mormon removal from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the “Rocky Mountains” where the church would be subject continued oppression and “obnoxious laws” against it in Congress “to destroy the White Horse.” In addition to foretelling other important world events, the prophecy states that the Constitution of the United States would almost be destroyed: “it will hang by a thread, as it were, as fine as the finest silk fiber.”[42]

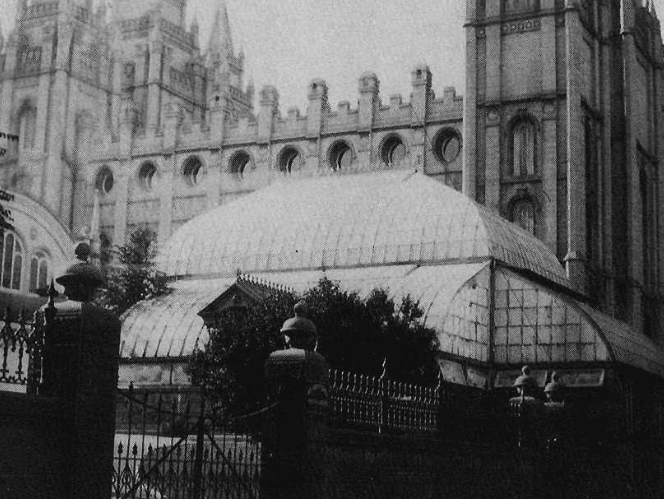

It is not surprising, then, that during the height of this increased millennial discourse, West’s Pale Horse was seen by Mormon audiences in Nauvoo, Illinois. On 12 June 1844 the Nauvoo Neighbor announced that “A Gentleman is now in our city who has for exhibition West’s painting of Death on the Pale Horse. We have not seen the exhibition, but judging from the known celebrety of the artist, and from the number of testimonies we have seen, it must be worthy of attention. The exhibition opens today at Gen. Smith’s Store and is to be continued for three days.”[43]

The name of the “Gentleman” who was promoting the celebrated piece as West’s is unknown. Unfortunately, any further newspaper coverage of the exhibition was preempted by news of the destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor press and the subsequent murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith at Carthage, Illinois, on 27 June. Allen Staley, a professor of art history at Columbia University and a West scholar, doubts that the piece shown at Nauvoo was authentic.[44] It is likely, however, that this painting was one of several which had been in exhibition and were purportedly by West’s hand. Nevertheless, it is still worthy of note that this painting was at Nauvoo during the Millerite year of the advent, the very year in which many were searching the skies for the opening of the Seven Seals.[45]

By 1850 apocalyptic art was virtually unseen. Art patronage during the Victorian age was more concerned with reason and order. Art that grew out of religious worship was supplanted by a reverence for pastoral serenity. The apocalyptic sublime was replaced by reasoned visions of a peaceful landscape. Still, Romantic painters such as Benjamin West continued to garner respect from devoted admirers, American and British alike. Decades after the passing of millenarian artists, John Ruskin wrote, “I believe that the four painters who have had, and still have, the most influence, such as it is, on the ordinary Protestant Christian mind, are Carlo Dolci, Guercino, Benjamin West, and John Martin.” Further he wrote, “[A] smooth Magdalen of Carlo Dolci with a tear on each cheek, or a Guercino Christ or St. John, or a Scripture illustration of West’s or a black cloud with a flash of lightning in it of Martin’s, rarely fails of being verily, often deeply, felt for the time.”[46]

[1] Joseph Smith Journal [kept by Willard Richards], 15 June 1844,157, Smith Collection, archives, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter cited LDS archives); see also Joseph Smith, An American Prophet’s Record: The Diaries and Journals of Joseph Smith, ed. Scott H. Faulring (Salt Lake City: Signature Books in association with Smith Research Associates, 1989), 492; Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. Brigham H. Roberts, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1964), 6:471 (hereafter cited as HC).

[2] J. F. C. Harrison, The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism, 1780-1850 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1979), 131-32,196.

[3] Morton D. Paley, The Apocalyptic Sublime (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 1.

[4] Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 42.

[5] Ira V. Brown, “Watchers of the Second Coming: The Millenarian Tradition in America,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 39 (Dec. 1952): 441-58; James H. Moorhead, “Between Progress and Apocalypse: A Reassessment of Millennialism in American Religious Thought, 1800-1880,” Journal of American History 71 (Dec. 1984): 524-42; Jon R. Stone, A Guide to the End of the World: Popular Eschatology in America, Religious Information Systems Series, vol. 12 (New York: Garland, 1993), esp. 19-29.

[6] John Gait, The Life , Studies, and Works of Benjamin West, Esq. President of the Royal Academy of London, Compiled from Materials Furnished by Himself . . . , pts. 1 & 2 (London, 1820). It has since been established that John West, father of Benjamin, came to Pennsylvania without a certificate of transfer, which shows that he was not in good standing with the Society of Friends and therefore his children were not members by birth. Charles Henry Hart, “Benjamin West’s Family; The American President of the Royal Academy of Arts Not a Quaker,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 32 (1908): 1-33.

[7] Ann Uhry Ābrams, “A New Light on Benjamin West’s Pennsylvania Instruction,” Winterthur Portfolio 17 (1982): 252. See also David H. Dickason, “Benjamin West on William Williams: A Previously Unpublished Letter,” Winterthur Portfolio 6 (1970): 127-33; William Sawitzky, “William Williams, First Instructor of Benjamin West,” Antiques 31 (May 1937): 240-42; Thomas F. Jones, A Pair of Lawn Sleeves: A Biography of William Smith, 1727-1803 (Philadelphia: Chilton, 1972); and Gait, Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin West, 37-40, 44, 68-74.

[8] Clarke Garrett, “The Spiritual Odyssey of Jacob Duche,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 119 (1975): 143-55.

[9] See Harrison, The Second Coming, 72-76, and W. S. Baker, William Sharp (Philadelphia, 1875).

[10] See William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, ed. Alexander Wyckoff, 3 vols. (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1965), 1:291-72; W. Roberts, “Thomas Spence Duche,” Art in America 6 (1918): 273-75; Albert Frank Gegenheimer, “Artist in Exile: The Spiritual Odyssey of Thomas Spence Duche,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 79 (1955): 3-26.

[11] Paley, Apocalyptic Sublime, 46-50. Allen Staley disputes this claim, saying “on good historical grounds, amply documented by Paley, we associate slightly later treatments of such themes with millenarian thought, and with responses to the French Revolution, the Terror and the Napoleonic wars, but in 1779 West was working for a patron whose first goal was to encourage a British school of history painting, and who had no sympathy with the radical masses in these images.” See Allen Staley, review of The Apocalyptic Sublime, by Morton D. Paley, in Burlington Magazine 129 (June 1987): 406.

[12] For a fuller discussion of Mortimer’s influence on West, see Norman D. Ziff, “Mortimer’s ‘Death on a Pale Horse,”‘ Burlington Magazine 112 (1970): 531-35.

[13] Mr. West’s Celebrated Picture,” Monthly Anthology 5 (Apr. 1808): 230.

[14] For a complete description and historiography of the painted versions, see Allen Staley, “West’s Death on the Pale Horse,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 58 (1980): 137-39, and Helmut von Erffa and Allen Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), cat. nos. 401-403, 410, pp. 388-92, 397-98.

[15] J. G. [John Gait], A Description of Mr. West’s Picture of Death on the Pale Horse ; or the Opening of the First Five Seals ; Exhibiting under the immediate patronage of His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, at 125, Pall Mall, near Carlton House (London, 181 7); William Carey, Critical Description and Analytical Review of “Death on the Pale Horse” Painted by Benjamin West, PR. A. . . . (London, 1817; reprinted in Philadelphia, 1836).

[16] Grose Evans, Benjamin West and the Taste of His Times (Carbonaie: Southern Illinois University Press, 1959), 63.

[17] John Dillenberger, Benjamin West: The Context of His Life’s Work with Particular Attention to Paintings with Religious Subject Matter . . . (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1977), 78-79, 89-93.

[18] Ruth S. Kraemer writes that the drawing “most likely represents a first idea for one of Benjamin West’s most famous and important paintings.” Kraemer, Drawings by Benjamin West and his son Raphael Lamar West (New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1975), 27.

[19] In 1931 Fiske Kimball proposed that the version dated 1802 was in fact the painting exhibited in Paris in 1802, rather than the 1796 version. Fiske Kimball, “Benjamin West Au Salon De 1802: La Mort Sur Le Cheval Pale,” Gazette des Beaux Arts 7 (1932): 403-10 (this is a lengthier version of his earlier article, “Death on the Pale Horse,” Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin 26 [Jan. 1931]: 17-21). Staley has convincingly disputed this claim, however. Staley, “West’s Death on the Pale Horse,” 137nl; von Erffa and Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West, 392.

[20] See Dillenberger, Benjamin West, 44-82, 92-93; Jerry D. Meyer, “Benjamin West’s Chapel of Revealed Religion: A Study in Eighteenth-Century Protestant Religious Art,” Art Bulletin 57 (June 1975): 257-59; “West’s Paintings for the Royal Chapel in Windsor Castle,” in von Erffa and Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West, App. I, 577-81.

[21] The Paintings of Benjamin West, 397-98.

[22] Joseph Farington, The Diary of Joseph Farington, vols. 1-6, ed. Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintyre (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), entry for 2 Sept. 1802, 5:1,823.

[23] Ibid., 12 and 24 Sept. 1875 (5:1,851, 1,875).

[24] See David Bjelajac, Millennial Desire and the Apocalyptic Vision of Washington Allston (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988); William Gerdts and Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., “A Man of Genius”: The Art of Washington Allston (1719-1843) (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1979); William Feaver, The Art of John Martin (London: Oxford University Press, 1975).

[25] Washington Allston to Charles Fraser, 25 Aug. 1801, in The Correspondence of Washington Allston, ed. Nathalia Wright (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993), 26. See also Jared B. Flagg, The Life and Letters of Washington Allston (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892), 43-44.

[26] Memoir of Benjamin West, Esq. President of the Royal Academy,” The Annual Register, or A View of History, Politics, and Literature of the Year 1820 (London, 1822), vol. 62, pt. 2, p. 1,172.

[27] Dunlap, Rise and Progress, 1:9 7.

[28] The Fine Arts,” Nile’s Weekly Register, 5 Mar. 1836, 4.

[29] West’s Death on the Pale Horse,” New York Mirror, 30 Apr. 1836, 364.

[30] Charles Coleman Sellers, “The Pale Horse on the Road,” Antiques 65 (1954): 384-87. See also Donald D. Keyes, “Benjamin West’s Death on the Pale Horse: A Tradition’s End,” Ohio State University College of the Arts: The Arts 7 (Sept. 1973): 3-6.

[31] David Bjelajac, “The Boston Elite’s Resistance to Washington Allston’s Elijah in the Desert,” in American Iconology: New Approaches to Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature , ed. David C. Miller (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 39-57. See also Tamara Plakins Thornton, Cultivating Gentlemen: The Meaning of Country Life Among the Boston Elite, 1785-1860 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989); E. Digby Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class (New York: The Free Press, 1958). For West’s status among the elite in revolutionary Philadelphia, see Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Rebels and Gentlemen: Philadelphia in the Age of Franklin (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962).

[32] Philip Hone, The Diary of Philip Hone, 1828-1851, ed. Allan Nevins (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1936), 207.

[33] New York Mirror, 3 Sept. 1836, 79.

[34] Harrison, The Second Coming, 131-33, 196-97, 217.

[35] Miller, Evidence from Scripture and History of the Second Coming of Christ, About the Year 1843: Exhibited in a Course of Lectures (Troy, NY: Kemble and Hooper, 1836). For a discussion on the opening of the fourth seal, see p. 45.

[36] See Francis D. Nichol, The Midnight Cry: A Defense of the Character and Conduct of William Miller and the Millerites (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1944); Michael Burkun, Crucible of the Millennium: The Burned-over District in New York During the 1840s (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1986).

[37] 37. See Grant Underwood, “The Religious Milieu of English Mormonism,” in Mormons

in Early Victorian Britain, Publications in Mormon Studies, Vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: University

of Utah Press, 1989), 40-44; W. H. Oliver, Prophets and Millennialists: The Uses of Biblical Prophecy

in England from the 1790s to the 1840s (New Haven: Oxford University Press, 1978), 218-38;

Dan Vogel, Religious Seekers and the Advent of Mormonism (Salt Lake City: Signature Books,

1988).

[38] Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1993), 112-18. See also Richard L. Anderson, “Joseph Smith and the Millenarian lime Table,” Brigham Young University Studies 3 (1960-61): 55-66.

[39] See, for example, Benjamin Winchester, “The Coming of Christ, and the Destruction

of the Wicked,” Gospel Reflector [Philadelphia] 1 (15 Apr. 1841): 220-24; 1 (1 May 1841): 225-43,

esp. 232-33. For a discussion of the development of the Mormon premillennial doctrine, see

Grant Underwood, “Seminal Versus Sesquicentennial Saints: A Look at Mormon Millennialism,”

Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 14 (Spring 1981): 32-44; also, Underwood, Millenarian

World , 25-29.

[40] See, for example, “Millerism,” Times and Seasons 4 (15 Feb. 1843): 103-106; “Millerism,” idem, 4 (1 Mar. 1843): 114-16; idem, 4 (15 Apr. 1843): 168-71; idem, 5 (1 Feb. 1844): 427; “Millerism,” idem, 5 (1 Mar. 1844): 454.

[41] Joseph Smith Journal [kept by Willard Richards], 2 Apr. 1843, LDS archives; Faulring, An American Prophet’s Record, 338-39; HC, 6:323.

[42] “A Prophesy [sic] of Joseph Smith,” MS [9 pp., undated, c. 1900-15], Special Collections and Archives, Merrill Library, Utah State University; Duane S. Crowther, “An Analysis of the Prophecy Recorded by Edwin Rushton and Theodore Turley which is Commonly Known as the ‘White Horse Prophecy/” in Prophecy – Key to the Future (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962), 301-22; Bruce R. McConkie, “White Horse Prophecy,” in Mormon Doctrine (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1979), 835-36; Ogden Kraut, The White Horse Prophecy (Salt Lake City: Pioneer Press, 1993). A discourse given in 1840 contained a similar reference to the U.S. Constitution on “the brink of ruin.” See Dean C. Jessee, “Joseph Smith’s 19 July 1840 Discourse,” Brigham Young University Studies 19 (Spring 1979): 390-94.

[43] Death on the Pale Horse,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 12 June 1844, 3.

[44] Dr. Allen Staley (Columbia University), telephone conversation, 27 Apr. 1994.

[45] I have not found further published reports of the exhibition in Mormon newspapers. However, when the Academy of Fine Arts was nearly destroyed by fire in 1845, the LDS Millennial Star reported the disaster and its losses. It also reported that “West’s ‘Death on the Pale Horse,’ Haydon’s ‘Christ’s, Entry into Jerusalem,’ and Alston’s ‘Dead Man Restored to Life,’ were preserved but with little injury” (“Destruction of the Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 6 [15 July 1845]: 46).

[46] John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol. 2, in The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, 39 vols. (London: George Allen, 1904), 10:125.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue