Articles/Essays – Volume 33, No. 2

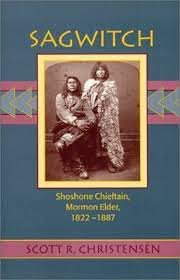

One Well-Wrought Side of the Story | Scott R. Christensen, Sagwitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder, 1822-1887

Scott R. Christensen has made an auspicious entry into the realm of Mormon history with his book Sagwitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder, 1822-1887. Already the volume has won the 1999 Evans Handcart Prize and the Award for the Best First Book in Mormon History from the Mormon History Association. Indeed, the book, developed from Christensen’s 1995 M.A. thesis at Utah State University, is a meticulously documented, well-il lustrated expansion upon Brigham Madsen’s inquiries into nineteenth century Shoshone history. Christensen often warns that Mormon interactions with Shoshones were hampered by a typical Anglo ethnocentrism. Despite his empathy with his subject and his research efforts, his narrative often falls into the same pitfalls of failing to see issues and events within a larger context.

Christensen begins by establishing a basic cultural and social context for the Northern Shoshone, relying primarily on authoritative secondary sources from Smithsonian publications. Once he launches into the historical narrative of his subject, however, his language becomes tenuous. He often assumes that Sagwitch, because of his tribal authority and prominence, is “probably” or “likely” in attendance at significant events but cannot offer direct evidence (e.g., 16, 18, 45, 101). Christensen also includes information from interviews with Sagwitch’s descendants, which he attributes to the repetitive “family traditions” (e.g., 9, 12, 14, 18, 29, 37, 67, 179). Of course, because written documentation of his topic reflects solely Anglo points of view, Christensen is placed in the difficult situation of having to make these assumptions, but this methodology also makes the book less a biographical study, more a regional historical recounting.

Once the narrative moves to the sequence of events leading up to the 1863 Bear River massacre, its documentary evidence is more sound, yet more revealing. Christensen has thoroughly examined and quoted representative contemporary newspaper reports, letters, and records from LDS church archives and Bureau of Indian Affairs records to discuss events in Cache Valley in the 1850s and 1860s. While he tries to remain sympathetic to a Shoshone point of view, however, his narrative shifts its focus from the life of Sagwitch to local history. In recounting events, Christensen slips into the language and point of view of the settlers by referring to the Indians as “troublesome” (38) and as committing “depredations” (30). Although he sup ports a linguistic shift from Bear River “Battle” to Bear River “Massacre” to describe the mass killing of Shoshone Indians in 1863, he also uses the settlers’ description of “massacre” to depict the killing of five white men in 1859 (28).

As thorough as this focused and detailed history of Northern Utah is, it lacks context, particularly in the history of American Indian tribal nations in the west. For example, the author states that the Bear River massacre “has the ignominious reputation of representing the single greatest loss of Indian lives in battle with whites” (xiii) in the Trans-Mississippi West. The narrative gives the number of dead Indians as “about three hundred,” although it later cites official reports numbering the dead between 224 and 235 (xiii, 53). The Bear River events are similar to the more famous, yet unmentioned, Sand Creek massacre of approximately 200 Indians just over a year later in neighboring Colorado, the Washita River massacre of 1868, and the Marias River massacre of 1871. The religious sentiments of some Mormons, who justified the events at Bear River as “intervention of the Almighty” (58), could easily be compared to the historiography of the Puritans, who justified the Pequot massacre in Biblical terms, or to their doctrinal rhetoric of what would later be labeled Manifest Destiny. While the author’s purpose is to focus on Sag witch and the consequence of the Bear River massacre in his life, providing such historical and geographical con text would have been helpful.

Likewise, other significant Utah and Mormon historical events connected to American Indians, like the Mountain Meadows massacre (1857) and the “Paiute prophet” (Wovoka or his father, Tavibo, neither named in the text), are also glossed over. The “Corinne Indian Scare” should have been elaborated further in relation to the complex and supposed Indian role at Mountain Meadows, and also the Fetterman Massacre of 1866 where Crazy Horse and his followers killed 80 U. S. soldiers in Wyoming, and other contemporary events in the U. S. west. The roles of Indian agents such as Reverend George W. Dodge, who was assigned to the Northern Shoshone (77), and their religious affiliations are not discussed or considered in the analysis of events. Other United States policies regarding American Indians, such as the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, surely had an impact on the Northern Shoshone community, but they are not addressed.

Most frustrating is the lack of analysis, despite detailing of chrono logical events, regarding Sagwitch and the Shoshone relationship with the Mormon church. For the non-Mormon reader, the connection between Ameri can Indians and the belief that they are “Lamanites” of the scriptural Book of Mormon needs fuller explanation. Clearly, as Christensen outlines, the initial Mormon attitude toward indigenous peoples generally differed from that of many colonizers of the American West. But the agenda of assimilation in the guise of “civilization” and education, even so far as the be lief that Indians could become “white and delightsome,” had more in common than not with the mainstream. The Mormons’ theological imperatives need to be discussed more explicitly. Christensen offers some religious practices such as healings, dreams, and visions that the nineteenth-century Shoshone may have found in common with Mormons. Nevertheless, the author admits that “it is impossible to know” (84) why Sagwitch and hundreds of Shoshones chose to be baptized into the Mormon church, nor is it clear why Sagwitch and some of his family later became disaffected. Al though his descendants offer some speculation, as does Christensen, Sag witch’s voice is conspicuously silent here, as through most of the narrative.

When I, as an American Indian, read this narrative, I recognize the desire of the author to present a balanced view. However, I am not necessarily part of the “we” of the narrative who interpret events a particular way. Reading Sagzvitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder, I am aware that this is not the story as the Shoshone historians would tell it or even the story an ethnohistorian would reconstruct.[1] Granted, reconstructing histories from oral traditions when the preponderance of documentation presents a sin gular point of view can be tremendously challenging, and Christensen has made a valiant effort. In her landmark book, The Legacy of Conquest, Patricia Nelson Limerick notes: “Scholars have long been preoccupied with the image of ‘the Indian’ in the Euro American mind; now, it is clear, others must make comparable studies of the image of ‘the white man’ in the Indian mind. In thinking about American Indian history, it has become essential to follow the policy of cautious street crossers: Remember to look both ways.”[2] Christensen’s book brings one aspect of Mormon history and Indian relations to the intersection.

Sagwitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder, 1822-1887, by Scott R. Christensen (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1999), 272 pp., $19.95 paper, $36.95 cloth.

[1] For an example of this kind of history, see Loretta Fowler’s Arapahoe Politics, 1851-1978 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982).

[2] Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: Norton, 1987), 181.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue