Articles/Essays – Volume 08, No. 2

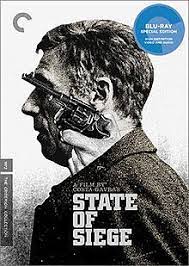

Opposition in All Things | Constantin Costa-Gavras, dir., and Franco Solinas, A State of Siege

At the time that Costa-Gavras’ new film, A State of Siege was cancelled at the American Film Institute’s inaugural festival at its new movie theater in Washington’s Kennedy Center, it was described as “rationalizing political assassination,” and thus conflicting with the spirit of an event honoring the late President Kennedy. However, a further reason is evident—that it insinuates American undercover agents in the uncomely role of advisor-trainers of repressive police in a South American dictatorship.

It is ironic that the appearance of this film and its rejection by the festival in Washington coincided with growing embarrassment of exposed illegal political repression within the United States. The necessity of political opposition, desirable without political violence, is the reality brought in focus by both this film and the network of political espionage and repression being unraveled by the Watergate hearings.

Costa-Gavras expresses his moral outrage at American involvement in the internal affairs of Latin America, using as a basis for the story, the 1970 kidnap murder by the Tupamaros, Uruguayan urban guerillas, of Don Mitrone, a United States Agency for International Development official, ostensibly assigned to ad vise the Uruguayan police in communications and traffic control, but subsequently reported to be involved in Uruguayan internal security and closely associated with those responsible for the systematic torture and liquidation of the revolutionary opposition. Much of the film’s direction was conceived after talking to people involved in the kidnapping and listening to tapes of Mitrone’s in terrogation by the Tupamaros.

The result is a combination of documentary and fiction, difficult for the viewer to distinguish. Costa-Gavras has said: “The movie is about political violence, rather than about political assassination. It tries to speak about violence from each side.” However, the film is not at all neutral. The Tupamaros are clean—they have the role of just inquisitors, clear-eyed, logical, knowing, of measured temperament. They try not to hurt the kidnap victims and they release an Ameri can agronomist and other non-political persons. They are grass-roots democrats, even going through a complicated voting procedure—meeting one-by-one on a moving bus—to determine whether to put the American agent to death when the Uruguayan government refused to negotiate the release of political prisoners. By contrast the police and government oligarchs are grossly overweight, pompous and insensitive, awash in self-righteous hypocrisy. A journalist asks whether the terrorists will demand release of political prisoners—the official’s answer: “We have no political prisoners here, only common criminals.”

The music and sequence reinforce the film’s moral conclusions. The industry and purpose of the elaborate guerilla efforts in organizing and effecting plans is underscored by industrious and purposeful music, quick paced and optimistic, sometimes resembling the musical background of industrial training movies.

The film begins with the search and discovery of the assassinated American, Philip Michael Santore. The body is found in the back of a Cadillac with Monte video license-plates, one of the many cars methodically appropriated for the kid napping. At this point the viewer is naturally revolted by the assassination. At a pompous funeral procession it is curiously observed that the places reserved for the university president and faculty are empty. The irony is developed when the eulogy calls Santore a victim of terrorism and violence. The ensuing account of Santore’s history with Brazilian and Dominican policy and his close involvement with those who inflicted electric torture, tends to leave us in sympathy with the clear-eyed revolutionaries.

The use of Yves Montand as the protagonist agent lends a subtlety to the argument, primarily because of his demeanor and objectivity. He is not by nature such a bad person. In fact, he is likeable; it is his job that condemns him. He responds to his interrogators briefly and pragmatically, trying to preserve his integrity as the evidence within each question exposes half truths and lies erroding his attempted innocence. The camera cuts from the interrogation room to scenes of the agent’s life, amplifying for the viewer the irony of the questions and answers.

Although Costa-Gavras has suggested that he has attempted only to show two enemies facing each other, each trying to rationalize their actions—execution by the Tupamaros and torture by the police—and that he never made moral judgments, the judgment against repression of a political opposition is power fully concluded, as it was in his two prior political films, Z, based on the assassination of Gregorio Lambrakis in Greece, and The Confession, a film about the Slansky trial in Czechoslovakia.

The underlying subject of each of these films is opposition and attempts to con trol or eliminate it. In resolving political and social conflicts within the United States we rely upon representative government, checks and balances, an adversary judicial system and a free press. The absence of these forms of political opposition often results in climates of political repression, such as those observed by Costa Gavras in Greece, Czechoslovakia and Uruguay. Repression to create unity is a violence and it often breeds counter-violence.

The message of A State of Siege in demonstrating the alternative to legitimate political opposition is amplified in meaning as we attempt to understand and dis mantle the efforts to centralize political power in our own country. This message applies equally to totalitarianism of the left—with its slogan “power to the people”—as to totalitarianism of the right. Wherever power is concentrated, it is wielded by specific individuals (never all the people) who often become a self-perpetuating “New Class” of functionaries.

Mormons believe that there “must needs be opposition in all things” (Nephi II). Yet how are we to respond to the oft expressed call for unity within the Church? Is there not one truth, one path? Is opposition desirable even within the Church? Maybe the practical question is what we do with opposition when it appears. Is a dialogue maintained or is expression outside of the litany of unified thought quieted? Does the comfort of unity insulate us from the responsibility of examination? Can the purpose of our life be simply prescribed by someone else, or must we sense and judge the evidences of our purpose, each person in his own heart coming to terms with the meaning of his life? A State of Siege, which explores a political state bridled by unified political control without the ideas or influence of a working opposition, is an effective vehicle for reminding us of the value of opposition.

A State of Siege, a film by Constantin Costa-Gavras and Franco Solinas.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue