Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 1

Orson Pratt, Jr.: Gifted Son of an Apostle and an Apostate

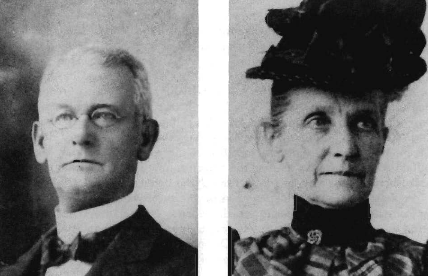

The distinction of being the firstborn of Apostle Orson Pratt’s forty five children belonged to his namesake, Orson Pratt, Jr. Unlike Joseph Smith III, Brigham Young, Jr., Joseph F. Smith, Heber J. Grant, John Henry Smith, John W. Taylor, Abraham O. Woodruff, and Abraham H. Cannon, young Orson did not follow the footsteps of his famous father into the hierarchy of Mormon leadership. Orson Pratt, Jr., endowed with the superior intellectual abilities of his father, became convinced in his early twenties that Joseph Smith was not the divinely inspired prophet of God he claimed to be. This loss of faith, publicly announced in 1864, resulted in young Pratt’s eventual excommunication. Though he lived in Salt Lake City for the remainder of his life, he never again affiliated with the church of his youth. Few people know the pathways his life took.

Born in Kirtland, Ohio, on 11 July 1837, to Orson Pratt and Sarah M. Bates, young Orson experienced early the uprooting displacements common to many saints during the Church’s infancy. After the collapse of Kirtland society in 1837 the Pratts lived briefly in Henderson, New York; St. Louis, Missouri; Quincy, Illinois; and Montrose, Iowa, before settling in Nauvoo in July 1839. Though Orson Pratt, Sr., was in the vanguard pioneer company of 1847, his family stayed temporarily in Winter Quarters, Nebraska. On 16 April 1848 Orson was appointed to preside over all branches of the Church in Europe as well as to edit the Millennial Star. Orson and Sarah and their three children left Winter Quarters for Liverpool on 11 May and arrived there on 26 July.

During the three years that the Pratts were in England, young Orson attended school and received excellent musical training under English masters. He was also allowed to help his father distribute missionary tracts, though he later said it was “not because I knew anything of what I was doing, but because I liked to see the old women, when they slammed the door, or threw the tracts into the streets in their anger” (Bleak n.d., 172-75).

In early 1851 the Pratts returned to the United States. They stayed in Kanesville, Iowa, only a short time while being outfitted and in July began the trek across the plains to the Salt Lake Valley. It was a trip remembered long afterwards by Orson, Jr. His father had engaged thirteen young, inexperienced men from England to drive his company to the Great Basin. The cattle were wild, and many wagons tipped over and were damaged during the three-month trip. One day a member of the company carelessly shot at a buffalo when the herd was near the wagon train. The startled animals stampeded between the wagons but fortunately no one was injured.

A short time later, while camped on the Sweetwater River in Wyoming, the company’s cattle were stampeded, evidently by Indians. While they were being rounded up, Sarah Pratt, who was eight months pregnant, rode on ahead in a carriage with fourteen-year-old Orson and his nine-year-old sister Celestia. As soon as the carriage was out of site of the company, an Indian, with knife in hand, sprang from ambush, grabbed the horse’s bits, and attempted to cut the animal loose. Fortunately, Sarah’s brother Ormus Bates had ridden after her, and the Indian fled as Ormus approached the carriage (M. Pratt 1891, 393).

Young Orson got his first glimpse of Salt Lake City from Big Mountain on 6 October. “All get out and have a view of the city,” his father had invited (M. Pratt 1891, 393). The next day they drove their wagons to Temple Square, which would be their temporary home for two weeks. They then moved to Plat A, Block 76, Lot 5, a property which had been previously developed by Parley P. Pratt and on which now stands the Marriott Hotel.

On 1 March 1852 fourteen-year-old Orson was endowed in the Endowment House (EHR, p. 38) and on 22 July Orson, Sr., rebaptized the entire family (Salt Lake Stake Record of Baptisms and Rebaptisms, 1847-63), a customary procedure for newly arrived Saints. One month later Orson, Sr., was sent on a mission to the eastern states to publish The Seer, a periodical advocating polygamy. Pratt, along with his wife Sarah, had opposed Joseph Smith’s method of introducing plural marriage in Nauvoo. But Orson later modified his position and eventually married nine additional wives. Sarah, however, stopped believing in Mormonism after Joseph Smith’s polyandrous proposals to her while Orson was absent on his 1840—41 mission to England. Though she viewed Smith’s propositions to her as “wicked” (Paddock to Gregg 1882), she nevertheless went along with Orson’s subsequent polygamy because of an “earnest, conscientious desire to do what was right as a Mormon, and to please a husband whom she loved with all the strength of her nature” (“Orson,” 1877, 2). During Orson’s 1852 mission, however, Sarah began to turn her children against Mormonism. She concealed her actions from neighbors, Church authorities, and her absent husband. “Fortunately my husband was almost constantly absent on foreign missions,” she explained in an interview cited in the 18 May 1877 New York Herald. “I had not only to prevent my children from becoming Mormons, I had to see to it that they should not become imbued with such an early prejudice as would cause them to betray to the neighbors my teachings and intentions.” She further explained to the reporter how she accomplished this:

Many a night, when my children were young and also when they had grown up so as to be companions to me, I have closed this very room where we are sitting, locked the door, pulled down the window curtains, put out all but one candle on the table, gathered my boys close around my chair and talked to them in whispers for fear that what I said would be overheard (“Orson,” 1877, 2).

Her actions had a dramatic effect on her children. None of the six who reached adulthood, except her deaf son, Laron, remained a practicing Mormon. The youngest son, Arthur, summed up the family’s feelings: “I will tell you why [I am not a Mormon],” he replied to a newspaper reporter in 1882. “I am the son of my father’s first wife, and had a mother who taught me the evils of the system” (Anti-Polygamy Standard, 11 [February 1882]: 81).

The family’s apostasy was carefully hidden for nearly twenty years. It was not until the spring of 1864 that Orson Pratt, Jr., became the first to openly announce his disbelief in Mormonism. Prior to this time his life seemed to be that of an exemplary Mormon. On 29 December 1854, the Deseret News reported that seventeen-year-old Orson had arranged an original song which was performed during the intermission of a two-act play at the Social Hall. On 23 May 1855 he sang in a quartet at the Deseret Theological Institute and also tried out a composition on the institute choir entitled “Although the Fig Tree Shall Not Blossom” (JH, under date).

One year later Orson Pratt, Sr., on another mission to England, announced his son’s marriage in the 6 December 1856 Millennial Star:

Married, in Great Salt Lake City . . . Mr. Orson Pratt, Junior, to Miss Susan Snow, daughter of Zerubabel Snow, formerly a United States’ Judge for that Territory. Ceremony by President Brigham Young . . . the 1st of October, 1856. The age of the bride groom is about 19 years, that of the bride about 15. May the God of our ancestor Joseph, who was sold into Egypt, bless them, and their generations after them, for ever and ever (18:784).

Young Orson seemed a believing Mormon at this point in his life. He bore his testimony in General Conference (Deseret News, 4 April 1857) and played the tabernacle organ in a private conference for Church leaders Brigham Young, Daniel Wells, George A. Smith, and Amasa Lyman (Deseret News, 28 June 1857). He was appointed to the Utah Board of Regents on 25 January 1859, and on 16 October of that year he was ordained a high priest and set apart as a Salt Lake Stake high councilman. But these events and positions of leadership occurred, according to young Pratt’s later testimony, while he was an “unbeliever” (Bleak n.d., 172-75).

We do not know precisely why Orson, Jr., served as a high councilman when he did not believe in Mormonism, but “closet doubters” have likely always permeated the folds of the faithful. D. Jeff Burton, in a 1982 essay on this phenomenon, noted that most doubters he examined were in their mid twenties to mid-forties. He felt that younger people “have neither the experience nor the education necessary to catalyze the complex reactions necessary to become a closet doubter” (p. 35). Orson Pratt, Jr., was only twenty-two when called to the Salt Lake Stake High Council. Evidently he felt intimidated to accept the position, perhaps as potential missionaries today sometimes find it easier to serve a mission than to say no. Possibly Orson, like his unbelieving mother, simply felt an “earnest, conscientious desire to do what was right as a Mormon” (“Orson” 1877, 2), perhaps feeling a testimony would grow from the calling.

Whatever the reasons for young Orson’s decision to hide his true feelings, by 1861 the wheels were slowly set in motion which ultimately led to his coming out of the closet of unbelief. Though still living in the Pratt homestead on West Temple and First South, young Orson was beginning to establish himself as a teacher. In February 1860 he had been hired as an instructor in Brigham Young’s Union Academy and in October became the first president of the Deseret Teachers Association (now the Utah Education Association). But the American Civil War was creating a cotton shortage, and Church leaders desired to establish their own cotton industry in southern Utah. Men of all walks of life were sent south on agricultural missions to develop the region. It was to be a family affair for the Pratts. Orson, Sr., was called to co-preside over the mission with Erastus Snow. Schoolteacher Orson Pratt, Jr., and cooper Albert Tyler (married to his sister Celestia), began the trek to Utah’s Dixie with their families in late October 1860.

The Pratts initially settled upriver in Rockville but in the spring of 1862 moved south the few miles to St. George. Though young Orson had limited means (the family lived in a tent), he was elected a city alderman on the first slate of officials after the city was granted its charter and also became the area’s first postmaster. On 2 May he was ordained a high councilman of the Southern Utah Mission by his father, who was apparently unaware of his son’s true feelings towards Mormonism. Young Orson played for church services and other functions on an organ his mother had brought from Salt Lake. He and Celestia and Albert were also involved with a local theatrical troupe. On Pioneer Day of 1862 they were all cast in “The Eaton Boy.” As winter approached, a company of young men formed a debating club which met often in the tent of Orson Pratt, Jr.

Brigham Young and Orson Pratt, Sr., seldom got along well after the Pratts’ difficulties with Joseph Smith in Nauvoo. Orson had sided with his wife against the Prophet, and Brigham never forgot that. Orson’s intellectual bent also irritated President Young, and the two frequently had philosophical disputes which usually resulted in Orson’s being sent on a distant mission.[1] In the spring of 1863, while Brigham Young was visiting in St. George, he apparently felt inspired to send young Orson on a mission, despite the fact that he was already a colonizing missionary. Orson explained to Young that he had experienced a change in his religious feelings and did not want to serve a mission. The Church President, perhaps believing that the missionary experience would effect a testimony, insisted on issuing the call. But after Young had returned to Salt Lake, Orson, Jr., decided to take a firm stand against the missionary venture. On 13 June 1863 Pratt wrote to President Young:

During your recent visit to Saint George, I informed you of the change that had taken place in my religious views, thinking that, in such a case, you would not insist on my undertaking the mission assigned me. You received me kindly and gave me what I have no doubt you considered good fatherly advice. I was much affected during the interview and hastily made a promise which, subsequent reflection commences me it is not my duty to perform. I trust that you are well enough acquainted with my character to know that I am actuated by none but the purest motives. I am grateful for the interest you have manifested in my wellfare and desire still to retain your friendship.

Should any thing hereafter occur to convince me that my present decision is unwise I shall be ready to revoke it.

Refusing a mission call in nineteenth-century Mormonism, unless special circumstances proved otherwise, was tantamount to an announcement of per sonal apostasy. President Heber C. Kimball of the First Presidency had made this clear in 1856 when he said: “When a man is appointed to take a mission, unless he has a just and honorable reason for not going, if he does not go he will be severed from the Church” (JH, 24 February 1856). Young Orson, son of Mormonism’s best-known missionary, resigned from the St. George High Council on 8 May 1864. Orson Pratt, Sr., en route to an Austrian mission, was not present to witness his son’s actions. But Apostle Erastus Snow, young Orson’s uncle by marriage, was not pleased with his decision and made some “feeling remarks” on the occasion. Accepting the resignation, he announced he “could not conscientiously, and in justice to the cause we are engaged in, refuse to Brother Pratt the liberty to with-draw from the Council as [his] statements of his veiws, doubting as he does, the divinity of the call of the Prophet Joseph Smith and the consequent building up of the Church” (JH, 8 May 1864).

One week after resigning, Orson, Jr., George A. Burgon, Charles L. Walker, and Joseph Orton, principals of the “Literary Mutual Improvement,” published the first issue of a semi-monthly manuscript newspaper, the Veprecula.[2] Each of the men contributed a foolscap page of matter in each issue, young Orson writing under the pen name of Veritas (truth). The 1 June 1864 issue contains an essay by him on reason and faith, the very issue with which he was struggling. The essence of his thoughts in the piece is that faith is not superior to reason. “Faith,” he argued, “which is supposed to arise in a mysterious manner and to be the result of direct supernatural agency . . . must be a careful and patient exercise of reason.” Similar ideas had been expressed by his father in 1853. Orson, Sr., wrote, “Before we can have faith in any thing we must first have evidence, for in all cases evidence precedes faith” (O. Pratt, 2:198). In perhaps reflecting on Mormon Church leaders’ disdain for intellectuals, including his father at times, young Orson concluded his essay by advising: “Let us tear aside the veil of hypocritical sanctity behind which, the seemingly pious conceal their moral deformity, at the same time that we respect the humble and sincere inquirer, although his doctrine may not be consistent with our own.”

Once young Orson’s disbelief became known in St. George, it was impossible for him to continue living there. Erastus Snow was apparently the chief source of difficulty. Young Orson, in an 18 September 1864 public speech made shortly before he returned to Salt Lake City, announced that Erastus Snow was not only a “snake in the grass” who had secretly worked against Apostle Orson Pratt until he had sought another mission, but that he had also met secretly with Orson, Jr.’s, wife, Susan, and had tried to turn her against her husband (Bleak n.d., 175). His efforts with his niece were unsuccessful, however, and Susan remained loyal to her husband.

Sarah Pratt recognized the untenable position the family was in and wrote to Brigham Young on 25 July 1864 requesting permission to return to Salt Lake City.

I cannot see my family suffer without making an effort to relieve them … . Orson [Jr.] has tried every means in his power to make a living but every thing fails. People are willing to send [their children] to school but cannot or will not pay. He has an offer of a very good situation if he will return to S.L. City. He can make a comfortable living for himself and perhaps assist me some. Albert Tyler and family are now distributors of both food and clothing. He has several hundred dollars due him for work, but cannot collect one cent. Himself and family are nearly all sick. He says he must do something or starve. Both Orson & Albert desire me to write to you upon the subject.

On 4 August Brigham Young wrote back to Sarah granting his permission for the Pratts and Tylers to leave St. George. He also told her he expected to be in the city on or near 12 September. On 1 September 1864, young Orson’s wife gave birth to their first child, Arthur Eugene. Seventeen days later, the family’s difficulties with Mormonism peaked. Church leaders apparently could tolerate young Orson’s divergent beliefs as long as they had been kept personal. After all, Brigham Young knew of his lack of testimony, did not demand his resignation from the high council, and even called him on a mission. But once the young man’s doubts were publicly aired when he announced his resignation from the high council, local leaders evidently felt compelled to convene a Church court. Given the unusual opportunity of “speaking in regard to my faith,” during an 18 September 1864 sacrament meeting, the twenty-seven-year old announced:

I wish to say that I have long since seen differently to this people and although I am not in the habit of saying anything in self justification, yet ever since I have been in this Church I have led a godly and upright life; at the same time, I resolved that I would accept nothing that my conscience would not receive. I was at eight years old, baptized into the Church, and I was brought up in the Church. Well if I had been asked at that time what I was baptized for, I should have said for the remission of my sins, for I had learned it all parrot like and I had confidence in Mormonism, as I had been brought up in it … . I came out again to the Valleys with my father and we were required to be baptized again, I complied, for all this time I was a believer in Mormonism. But sometime afterwards, there was much said . . . that unless one had the testimony that Mormonism is true, there was something deficient. I asked myself the question, if I had it but was sensible I had not … . I have come to the conclusion that Joseph Smith was not specially sent by the Lord to establish this work, and I cannot help it, for I could not believe otherwise, even if I knew that I was to be punished for not doing so; and I must say so though I knew that I was to suffer for it the next moment (Bleak n.d., 172-75).

In spite of his frankness, or perhaps because of it, Orson Pratt, Jr., was excommunicated that night for “unbelief” by the St. George High Council. Shortly thereafter the entire Pratt family made the long northward trek back to the Salt Lake Valley.

Orson found work teaching music. He and his young family initially lived with his mother in the Seventeenth Ward home of Franklin B. Woolley which she had traded for her St. George home. On 12 March 1868, Orson, Jr., and Susan, with their two sons, moved with Sarah Pratt into the old Pratt home stead south of Temple Square. Orson, Sr., and Sarah had separated over polygamy difficulties, and she rented part of her home to young Orson for fifteen dollars a month (O. Pratt 1868).

Young Orson’s chief passion in life was music. Not only did he devote his life to teaching the subject, but he also frequently served as piano accompanist to noted artists who performed in the Salt Lake Theatre and elsewhere in the city. He donated his musical talents during holidays, much to his wife’s chagrin. “Orson is out to a party again tonight,” she wrote in her diary on 3 January 1872. “No,” she corrected herself, “I have made a mistake—it is entertainment given to get money and Orson donates his services as Organist.” His musical abilities were viewed with critical acclaim on numerous occasions. A review of his 6 January 1895 performance noted:

Many have called him too legitimate, too technical, but if it is a fault it is a most virtuous one, when performing the exacting phrases of the major oratorial and orchestral works of the masters. Granted that he is a long way inland from the wish-washy surf of expressive piano delivery, but he is at the very same distance from loose-jointed nauseous inaccuracy. So why wait longer to render this just praise? His accompaniments to the “Hymn of Praise” were perfect works. No sentimental ritards, or ad libitums, but the all-around brilliant setting to the intricacies of the vocal fabric.

Mr. Orson Pratt, Jr., for years an eminent pianist and teacher of theory and harmony in Utah, is a son of the apostle, himself an apostle, though on lines quite apart from the father. As it has been hinted above that he is a purist in instrmentation, so it may be added that he is a very valuable example of a much-neglected art, that of exact musicianship (JH, under date).

Though Orson’s life passion was music, he had other interests as well. He was a superb chess player. He and his younger brothers Arthur and Harmel at one time defeated a world-class Austrian player, Herr Zukertort. Orson was also an avid student of art and literature and constantly encouraged his wife and children to improve their minds. Susan Pratt wrote in her diary on 26 November 1871: “I have learned .. . at a late hour the value of intelligence, and I shall endeavor to instill into the minds of the children while young both a love and a just valuation of books.”

Orson also dabbled in politics and in 1870 ran for Salt Lake City council man. Though a candidate on the Liberal ticket, he was not the rabid anti Mormon some members of that party were. Like others in the valley, Orson apparently felt that non-Mormon interests simply had no political voice in Salt Lake City affairs. Because Orson was unsuccessful in his bid for a council seat, his political views were not heard publicly. However, his younger brother Arthur used his position as a law enforcement officer to publicly vent his feelings against Mormonism (see Van Wagoner and Van Wagoner 1987). Following his political defeat, Orson retreated back to his music.

Apostate Mormons like Orson, with no conversion potential, generally suffered more ostracism in Salt Lake City than did gentiles. Expose writers T. B. H. and Fanny Stenhouse, for example, left the city in 1874 after being assaulted by a group of rowdies. Wealthy merchant William S. Goodbe lost $100,000 in a two-year period because of a Church-organized boycott against him and other non-Mormon merchants (Van Wagoner and Walker 1982, 342, 97). Despite the social problems one might expect Orson to have in the city, he had little trouble keeping his music classes full, though the family was essentially quite poor until the early 1880s. The children often complained to their mother about the patches on their clothing, and by 1875 Orson and Susan still could not afford a piano on which to teach their own children.

In 1879 tragedy struck the family. Herbert Oliver Pratt, Orson and Susan’s five-month-old son, died suddenly. The parents were distraught. It was nearly two years before Susan could write of the death in her diary. Even then the memories were painful. “Untill now I have never felt as though I could write a word about it,” she noted on 17 August 1880, “and even now I would say nothing more. How little I know myself[,] at the very time I seem to have forgotten most I remember the keenest.” In an apparent attempt to assuage the family’s grief, Zerubbabel Snow, Susan’s father, gave them a home on Commercial Street which was large enough to hold Orson’s classes. Not having to pay rent, they were soon able to save enough money for a piano and to hire domestic help as well. A continuation of the 17 August 1880 entry in Susan’s diary provides a window into their daily lifestyle:

At seven oclock in the morning much against my will I concluded to get up and barely had time to dress before breakfast was on the table. I was soon seated in unkept hair with the children who had followed their mother’s example when we breakfasted on Biscuits, Bacon, and Coffee. Eight oclock came, and Orson went into the music room and I to my work which was sweeping. Part of the sweeping I had to leave for the girl as my back troubled me to much I then laid down with a book untill it was time to prepare for dinner[.] I then went out to see how far I could make my money go. Dinner was at last on the table and all around the board. In the afternoon I practiced and called Gertrude in to take a lesson. She was very listless and I lost my temper. I sent her out of the room for which I did not feel satisfied and called her back. We began again and got along very well. I read the rest of the day and far into the night as usual, was visited with compunctions as to the manner of spending my time and resolved before going to sleep to do differently to morrow.

The Pratts’ lifestyle continued to improve with time. By 1884 an increase in the number of Orson’s music students enabled them to move to a larger home at 223 South Sixth East. Their children received educations at St. Mark’s High School, a bastion of anti-Mormonism in the valley. The eldest son, Arthur Eugene, after attending the University of Utah, went east to study law at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor where he graduated in 1890, subsequently becoming a prominent Ogden judge (Clarke 2:260-61). The 1880s saw the death of both of Orson’s parents. Orson, Sr., who had been suffering from diabetes, died on 3 October 1881. Since the mid-1860s, however, young Orson and his father had not been close. Orson, Sr., not only was away on missions most of the time, but even when he was home, Church work and scientific activities occupied most of his time. Sarah noted that Orson “gradually became estranged from [his children]. He spoke harshly to them. He had and has no interest in their careers” (“Orson,” 1877, 2).

John Nicholson, a missionary acquaintance of Orson, Sr.’s, recalled an incident which further suggests the apostle was less than involved with his children. Orson, Sr., had just returned to Salt Lake City from a mission when one of his sons met him on East Temple Street. “He [the son] approached him and enquired about his health,” Nicholson recalled. “The response was: ‘I am well, thank you, but really you have the advantage of me. What is your name?’ When the identity of the young man was disclosed to him he felt somewhat annoyed and offered a polite apology, which he was assured was unnecessary” (Nicholson 1899, 22).

Sarah was much more involved with her children. Young Orson and Susan lived with his mother for more than a decade. After she sold her home in 1881 she occasionally lived with them as well as with her other children. After years of suffering with a rheumatic heart, Sarah died on 25 December 1889.

Ten years after Orson, Sr.’s death, his estate was distributed to “certain of the heirs of the deceased to the exclusion of others” (“Final Decree,” 1891). Apparently Sarah Pratt’s children, legal heirs, led by Orson Pratt, Jr., had claimed his entire estate (Block 111, Plat D). A countersuit, filed by children of Orson’s polygamous marriages, however, resulted in a 1 June 1891 Utah Supreme Court decision which gave each of the surviving children 1/32 of the estate (“Final Decree”).

By the turn of the century Orson, Jr.’s, health had begun to deteriorate. Evidently he, along with his brothers and sister, had inherited their mother’s cardiovascular problems which resulted in relatively early deaths for all of them. Orson, Jr., lived longer than any of his siblings, dying on 6 December 1903 at the age of sixty-seven. His widow, Susan Lizette Snow Pratt, outlived her husband by twenty-four years. She died on 16 March 1927. Both are buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

Though Orson Pratt, Jr., embraced no other religion following his 1864 excommunication, he was hardly the demented, anguished man portrayed by Mormon novelist Maurine Whipple in her critically acclaimed The Giant Joshua (1941). Nor was Whipple’s version of Susan’s damning testimony and alienation from Orson accurate. Despite pressure and worsening relation ships with family and friends, Susan Pratt neither testified against her husband nor withdrew her support from him. To the contrary, she joined with him in raising their children outside Mormonism. Retrospectively the family seems to have been a successful unit blessed with rich life experiences. Had Sarah Pratt’s introduction to Nauvoo polygamy come under different circumstances, perhaps young Orson would have followed in his father’s footsteps. But instead he chose a different pathway to an apparently worthwhile and fulfilling life.

[1] For discussions of the difficulties between Orson Pratt and Brigham Young see Gary James Bergera, “The Orson Pratt-Brigham Young Controversies: Conflict Within the Quorums, 1853 to 1868,” DIALOGUE 13 (Sumer 1980) : 7-58, and Breck England, The Life and Thought of Orson Pratt (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1985).

[2] For background on the Veprecula see the Charles Lowell Walker Papers and the Joseph Orton Diary, both in the LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City. The volume containing the biweekly issues of the original is in the possession of Katherine Miles Larson (see Andrew Karl Larson, Erastus Snow: The Life of a Missionary and Pioneer for the Early Mormon Church [Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1971], p. 272).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue