Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 1

Our LDS Hymn Texts: A Look at the Past, Some Thoughts for the Future

Our LDS hymn texts are a fascinating key to the history of the Church and the changing attitudes and concerns of the saints. Since the publication of the vest pocket hymnal of 1835, each new edition of the hymn book has sought to meet the current needs of the members: new, relevant hymns have been added, and old hymns have fallen by the way—some eliminated because they referred to problems that were no longer immediate, some because they expressed an attitude or teaching (such as millenialism or gathering-to-Zion) no longer emphasized in the Church, and others because they were not thought to be of sufficiently high artistic quality. In the Ensign for March, 1974, the Church Music Department announced that the LDS hymn book is once again to be revised.[1] The upcoming new edition provides a good opportunity to measure our hymns by a few aesthetic yardsticks, as a help not only in deciding once more which hymns to keep and which to drop, but also in sensing what sorts of new hymns are likely to be of more than temporary significance.

In judging the merit of a hymn text, the same questions can be asked that are usually asked of poetry: Are subject and tone appropriate? Is the point of view consistent? Does the text have unity as well as variety within that unity? Do the mechanics—rhyme, meter, comparisons, word choice—underline the meaning? At the same time, however, there are some differences between a hymn text and other kinds of poetry. A good hymn is not a strictly private sentiment; it must have community significance. A second limitation is length: though the early saints sometimes managed twelve or fourteen verses at a single sitting, the modern writer of hymn-texts knows that he must limit himself to three or four. And since, in traditional hymn-writing at least, succeeding verses must be sung to the same music, metrical variations which would add welcome interest in another poem would present considerable difficulty in a hymn.[2]

Of the 166 hymns by LDS writers in our hymn book,[3] more than a third are the work of five contributors: Parley P. Pratt, Eliza R. Snow, William W. Phelps, Evan Stephens, and Joseph Townsend. Pratt’s ten hymns seem to be the most consistently sensible and satisfactory. His well-known “As the Dew from Heaven Distilling” is an example of a simple, competent, carefully worked-out hymn:

As the dew from heaven distilling

Gently on the grass descends

And revives it, thus fulfilling

What thy providence intends,Let thy doctrine, Lord, so gracious,

Thus descending from above,

Blest by thee, prove efficacious

To fulfil thy work of love.Lord, behold this congregation;

Precious promises fulfil;

From thy holy habitation

Let the dews of life distil.Let our cry come up before thee;

Thy sweet Spirit shed around,

So the people shall adore thee

And confess the joyful sound.

The comparison of heavenly blessings to dew—the welcome, life-giving moisture that appears quietly and unaccountably—lends interest to what would otherwise be an undistinguished request for the spirit of the Lord. Pratt develops this single parallel in simple trochaic meter, and it is perhaps because of the trochaic (stress unstress) meter that the feminine (two-syllable) rhymes, such as “distilling” and “fulfilling,” do not seem intrusive. The long introductory “as”-clause gently reveals, with the word “thy” in the fourth line, our Heavenly Father as the focus of this hymn of supplication. The last line of verse 3, referring to the “dews of life,” gives a nicely circular and conclusive feeling to the hymn, and verse 4, no longer speaking figuratively, is a strong, final request for the spirit of the Lord. These same kinds of strengths may be seen in others of Pratt’s hymns, notably “The Morning Breaks; The Shadows Flee” and “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth.” Less effective hymns by Pratt are “Ye Children of Our God,” “Truth Eternal,” and “Ye Chosen Twelve.”

The merit of Eliza R. Snow’s contributions varies widely. The dignity of “How Great the Wisdom and the Love” and “Again We Meet Around the Board” contrasts startlingly with the nagging “Truth Reflects Upon Our Senses,” the mixed comparisons of “Thou Dost Not Weep,” and the triteness of “Great Is the Lord; ‘Tis Good to Praise.”

William W. Phelps was a writer ever at the ready, turning out hymns for any need or occasion. He is represented at his best by “Gently Raise the Sacred Strain” and “O God The Eternal Father,” at his worst by “Praise to the Man” (in dactylic meter, usually too rollicking to work well for a hymn, and with an incoherent fourth verse), and by “We’re Not Ashamed to Own Our Lord” and “Now We’ll Sing With One Accord” (both texts troubled by padded diction and lack of unity, and the second by a mystifying rhyme scheme as well).[4]

Evan Stephens has written some very popular, energetic hymns but tends to weaken his writing through the use of “twins”—the filling out of the meter through the use of two words where one would suffice: “great and mighty,” “great and grand,” “grand mountains high.” Since he wrote his own music as well, it is difficult to understand why he chose to fit the strongest musical stresses to the least important words—”which,” “the,” and “and,” for example, in “Father, Thy Children to Thee Now Raise.”

The least gifted of these five major contributors is Joseph Townsend. His texts are trite and repetitious—”Oh What Songs of the Heart” and “O Holy Words of Truth and Love,” for example. His finest text, “Reverently and Meekly Now,” has Christ as the speaker—an unusual, and possibly disturbing, point of view.

Texts by other LDS writers range in quality as widely as the ones we have mentioned, from the predictable and static “Come Along, Come Along” of William Willes to the excellent texts of Frank I. Kooyman. The most respectable hymns by both LDS and non-LDS writers alike seem to be those which fall within the cate gory of the “true hymn,” defined by Alexander Schreiner as “a sacred song ad dressed to Deity . . . always spiritual in quality.” The poorest, on the other hand, are often “gospel hymns,” “songs with refrains . . . dotted, dancing rhythms . . . not considered to be very high in either poetic or musical quality.”[5] Many of these gospel hymns seem to be the best candidates for omissions to make room for the “one or two hundred” new hymns that Dr. Schreiner would like to see come forth.[6] It would be unrealistic to suggest that all such gospel hymns should be dropped, since too many favorites are among them, including “It May Not Be on the Mountain Height,” “When Upon Life’s Billows,” and “You Can Make the Pathway Bright.” But since the General Church Music Committee has suggested that most of these songs are appropriate only for meetings other than Sacrament Meeting, and since many refer by name to the Sunday School and youth auxiliary programs, perhaps the best of them could be retained in a separate volume, not in the hymnal to be used at Sacrament Meeting.

In our excitement over the promised hymn book, we look forward to new hymns that reflect the achievements, the character and the concerns of the Church in the present day. As Dr. Schreiner has said, “We would be well advised to keep abreast of the times and write new hymns whose messages refer to the present day .. . in our new hymns we should strive for new subjects.”[7] As we consider the editorial history of our hymn book, however, it might be valuable to make an important cautionary point. The “occasional” hymns, the hymns that have referred over directly to current events, are no longer with us. It oversimplifies matters, therefore, to say that we should write about whatever is all-consumingly important to us in the gospel today. Our best texts have been those that do not stress our “peculiarity.” Bald, unstylized statements of doctrine, explanations of programs, belong in talks, not in hymn texts. In other words, we can write about kindness and charity, but probably not the welfare system; about ties of love and kinship, but probably not genealogy; about obedience, but probably not food storage.

LDS composer Lynn Shurtleff has observed in this regard that “what is really important is not the fact that we compose a song which contains the words temple or baptism, but that we give new insights, new attitudes about temples and baptism through our composition.”[8] Dr. Schreiner agrees that “hymns should express deep testimony (without using the word).”[9] The more generalized hymns are more successful; we should teach and take pride in our unique doctrine and circumstances, but the more specifically our hymns refer to these unique matters, the less successful, as hymns, they are likely to be. In writing about ourselves, we tend to fall into certain traps: we are didactic, or we are defensive, or we are boastful. We try to cram a catechism into a hymn (“What Was Witnessed in the Heavens?”) or, even with as experienced a hymn-writer as Eliza R. Snow and as basic a doctrine as the Word of Wisdom, we end up with something as static and as commonplace as “The Lord Imparted From Above.” Though an exceptionally skillful poet might refer to the welfare plan without excessive self-congratulation and without writing a hymn that will one day seem agonizingly out of date, such a feat does not seem very likely.[10]

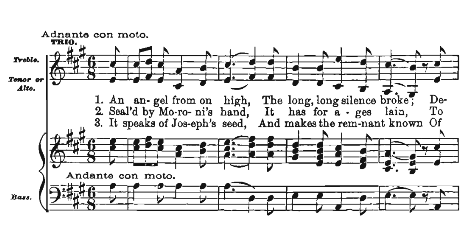

There are at least two important reasons the Hymn Book Committee might ex amine the older volumes of hymns as well as our present one. For one thing, some of the editorial changes made in the past are open to question. For example, the last lines of verse two of “An Angel from on High” are printed in our hymn book as

It shall again to light come forth

To usher in Christ’s reign on earth.

These lines are a doubtful improvement over Parley P. Pratt’s original

It shall come forth to light again

To usher in Messiah’s reign.

The monosyllables of “Christ’s reign on earth”—especially the word “Christ’s”— are difficult to sing, and “on earth” seems redundant and needlessly explanatory. The older hymn book may contain, as well, some discarded texts that would serve as fine hymns if set by skillful composers. Possibilities, to give just two examples, are Parley P. Pratt’s “Hark! Listen to the Gentle Breeze” and W. W. Phelps’s “See How the Morning Sun.”

The early collections contain many texts which give delightful and revealing insights into the life, thought, and culture of the early Church. It might be interesting to publish a small volume of hymns which would not be for general congregational use but would be of great historical interest, perhaps useful in marking important anniversaries in Church history. How intrigued some of our young people would be if they could know W. W. Phelps’s “O, Stop and Tell Me, Red Man,” his “Our Gallant Ship is Under Weigh” (one of many spirited hymns reflecting early missionary zeal), or Emily H. Woodmansee’s hymn marking the founding of the Relief Society:

. . . And not in the rear, hence, need woman appear;

Her star is ascending, her zenith is near . . .

Though the hymn book must of necessity select hymns that are of greater poetic merit, a collection of historical hymns might serve a valuable function in preserving the forthright and refreshing enthusiasm of the early saints.

[1] “Preparation Underway for New Church Hymnbook—Saints Invited to Submit Music and Texts,” Ensign, 4 (March, 1974), 73-74.

[2] An example of such a variation occurs in the last verse of “The Morning Breaks; The Shadows Flee.” Parley P. Pratt has substituted a trochaic foot for the iambic foot that would normally begin the verse. Though this reversed initial foot is a common variation, occurring often and unobtrusively throughout English poetry, the musical setting forces us to sing “an-gels,” and the variation is unnatural and awkward. It should be pointed out, however, that in setting up the rhythm of the syllables initially, the hymn-writer has in one way more liberty than a poet writing in traditional meter: he is freer to mix duple and triple feet simply because the composer is free to vary the number of notes, and thus accommodate varying numbers of syllables, between the initial strong stresses of the measures. There is considerable freedom, therefore, in the choice of the pattern of the first verse, but subsequent verses must not depart once the form has been established.

[3] Here, and later in the article, I have been liberal in my definition of “LDS hymn text.” Many hymns, including “Come, Come Ye Saints” and “Praise to the Man,” were based to a greater or lesser degree on already existing non-LDS texts. For a discussion of these derivations, see Helen Hanks Macare’s un- published dissertation “The Singing Saints: A Study of the Mormon Hymnal, 1835-1950” (UCLA, 1961).

[4] “Earth, With Her Ten Thousand Flowers,” although attributed to Phelps in the hymnal, is in fact by Thomas Rawson Taylor (1807-1835). See Macare, pp. 126-127.

[5] “Guidelines for Writing Latter-day Saint Hymns,” Ensign, 3 (April, 1973), 53, 54.

[6] Schreiner, p. 52. The length of the hymnal is not a serious problem. The present hymnal is only half as long as many Protestant hymnals, and a great number of hymns could be added without making the volume unmanageable.

[7] Schreiner, pp. 52-53.

[8] “Some Thoughts from Brother Ludwig, or: If Beethoven Were a Mormon,” Notes of the L. D. S. Composers Association, 2 (1971), 24.

[9] Schreiner, p. 58.

[10] It would be foolish, of course, to maintain that a uniquely LDS subject could not be the subject of a fine hymn. No subject is more peculiarly LDS than the restoration of the gospel, and “The Morning Breaks; The Shadows Flee” is among the best hymns in our collection. The treatment is figurative, un- specific, and very effective.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue